Dao (sword)

Dao (pronunciation: [táu], English approximation: /daʊ/ dow, Chinese: 刀; pinyin: dāo) are single-edged Chinese swords, primarily used for slashing and chopping. The most common form is also known as the Chinese sabre, although those with wider blades are sometimes referred to as Chinese broadswords. In China, the dao is considered one of the four traditional weapons, along with the gun (stick or staff), qiang (spear), and the jian (double-edged sword), and among them is called "The Marshal of Weapons".

| Dao | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_MET_DP-834-001.jpg) A Chinese dao and scabbard of the 18th century | |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 刀 | ||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | (single-edged) sword weapon with a single-edged blade knife | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Name

In Chinese, the word 刀 can be applied to any weapon with a single-edged blade and usually refers to knives. Because of this, the term is sometimes translated as knife or sword-knife. Nonetheless, within Chinese martial arts and in military contexts, the larger "sword" versions of the dao are usually intended.

General characteristics

While dao have varied greatly over the centuries, most single-handed dao of the Ming period and later, and the modern swords that are based on them share a number of characteristics. Dao blades are moderately curved and single-edged, though often with a few inches of the back edge sharpened as well; the moderate curve allows them to be reasonably effective in the thrust. Hilts are sometimes canted, curving in the opposite direction of the blade which improves handling in some forms of cuts and thrusts. Cord is usually wrapped over the wood of the handle. Hilts may also be pierced like those of jian (straight-bladed Chinese sword) for the addition of lanyards, though modern swords for performances will often have tassels or scarves instead. Guards are typically disc-shaped and often cupped. This was to prevent rainwater from getting into the sheath, and to prevent blood from dripping down to the handle, which would make it more difficult to grip. Sometimes guards are thinner pieces of metal with an s-curve, the lower limb of the curve protecting the user's knuckles; very rarely they may have guards like those of the jian.

Other variations to the basic pattern include the large bagua dao and the long handled pudao.

Early history

The earliest dao date from the Shang Dynasty in China's Bronze Age, and are known as zhibeidao (直背刀) – straight backed knives. As the name implies, these were straight-bladed or slightly curved weapons with a single edge. Originally bronze, these weapons were made of iron or steel by the time of the late Warring States period as metallurgical knowledge became sufficiently advanced to control the carbon content. Originally less common as a military weapon than the jian – the straight, double-edged blade of China – the dao became popular with cavalry during the Han dynasty due to its sturdiness, superiority as a chopping weapon, and relative ease of use – it was generally said that it takes a week to attain competence with a dao/saber, a month to attain competence with a qiang/spear, and a year to attain competence with a jian/straight sword. Soon after dao began to be issued to infantry, beginning the replacement of the jian as a standard-issue weapon.[1][2] Late Han dynasty dao had round grips and ring-shaped pommels, and ranged between 85 and 114 centimeters in length. These weapons were used alongside rectangular shields.[3]

By the end of the Three Kingdoms period, the single-edged dao had almost completely replaced the jian on the battlefield.[4] The jian henceforth became known as a weapon of self-defense for the scholarly aristocratic class, worn as part of court dress.[5]

Sui, Tang, and Song

As in the preceding dynasties, Tang dynasty dao were straight along the entire length of the blade. Single-handed peidao ("belt dao") were the most common sidearm in the Tang dynasty. These were also known as hengdao ("horizontal dao" or "cross dao") in the preceding Sui dynasty. Two-handed changdao ("long dao") or modao were also used in the Tang, with some units specializing in their use.[6]

During the Song Dynasty, one form of infantry dao was the shoudao, a chopping weapon with a clip point. While some illustrations show them as straight, the 11th century Song military encyclopedia Wujing Zongyao depicts them with curved blades – possibly an influence from the steppe tribes of Central Asia, who would conquer parts of China during the Song period. Also dating from the Song are the falchion-like dadao,[7] the long, two-handed zhanmadao,[8] and the long-handled, similarly two-handed buzhandao (步战刀).

Yuan, Ming and Qing

With the Mongol invasion of China in the early 13th century and the formation of the Yuan dynasty, the curved steppe saber became a greater influence on Chinese sword designs. Sabers had been used by Turkic, Tungusic, and other steppe peoples of Central Asia since at least the 8th century CE, and it was a favored weapon among the Mongol aristocracy. Its effectiveness for mounted warfare and popularity among soldiers across the entirety of the Mongol empire had lasting effects.[9]

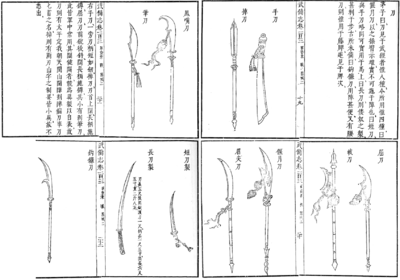

In China, Mongol influence lasted long after the collapse of the Yuan dynasty at the hands of the Ming, continuing through both the Ming and the Qing dynasties (the latter itself founded by an Inner Asian people, the Manchu), furthering the popularity of the dao and spawning a variety of new blades. Blades with greater curvature became popular, and these new styles are collectively referred to as peidao. During the mid-Ming these new sabers would completely replace the jian as a military-issue weapon.[10] The four main types of peidao are:[11][12]

Yanmaodao

The yanmaodao or "goose-quill saber" is largely straight like the earlier zhibeidao, with a curve appearing at the center of percussion near the blade's tip. This allows for thrusting attacks and overall handling similar to that of the jian, while still preserving much of the dao's strengths in cutting and slashing.[13]

Liuyedao

The liuyedao or "willow leaf saber" is the most common form of Chinese saber. It first appeared during the Ming dynasty, and features a moderate curve along the length of the blade. This weapon became the standard sidearm for both cavalry and infantry, replacing the yanmaodao, and is the sort of saber originally used by many schools of Chinese martial arts.[14]

Piandao

The piandao or "slashing saber" is a deeply curved dao meant for slashing and draw-cutting. This weapon bears a strong resemblance to the shamshir and scimitar. A fairly uncommon weapon, it was generally used by skirmishers in conjunction with a shield.[15]

Niuweidao

The niuweidao or "oxtail saber" is a heavy bladed weapon with a characteristic flaring tip. It is the archetypal "Chinese broadsword" of kung fu movies today. It is first recorded in the early 19th century (the latter half of the Qing dynasty) and only as a civilian weapon: there is no record of it being issued to troops, and it does not appear in any listing of official weaponry. Its appearance in movies and modern literature is thus often anachronistic.[16][17]

Besides these four major types of dao, the duandao or "short dao" was also used, this being a compact weapon generally in the shape of a liuyedao.[18] The dadao saw continued use, and during the Ming dynasty the large two-handed changdao and zhanmadao were used both against the cavalry of the northern steppes and the wokou (pirates) of the southeast coast; these latter weapons (sometimes under different names) would continue to see limited use during the Qing period.[19] Also during the Qing there appear weapons such as the nandao, regional variants in name or shape of some of the above dao, and more obscure variants such as the "nine ringed broadsword", these last likely invented for street demonstrations and theatrical performances rather than for use as weapons. The word dao is also used in the names of several polearms that feature a single-edged blade, such as the pudao and guandao.

The Chinese spear and dao (liuyedao and yanmaodao) were commonly issued to infantry due to the expense of and relatively greater amount of training required for the effective use of Chinese straight sword, or jian. Dao can often be seen depicted in period artwork worn by officers and infantry.

During the Yuan dynasty and after, some aesthetic features of Persian, Indian, and Turkish swords would appear on dao. These could include intricate carvings on the blade and "rolling pearls": small metal balls that would roll along fuller-like grooves in the blade.[20]

Recent history

The dadao was used by some Chinese militia units against Japanese invaders in the Second Sino-Japanese War, occasioning "The Sword March". The miaodao, a descendant of the changdao, also saw use. These were used during planned ambushes on Japanese troops because the Chinese military and patriotic resistance groups often had a shortage of firearms.

Most Chinese martial arts schools still train extensively with the dao, seeing it as a powerful conditioning tool and a versatile weapon, with self-defense techniques transferable to similarly sized objects more commonly found in the modern world, such as canes, baseball or cricket bats, for example. There are also schools that teach double sword shuangdao 雙刀, forms and fencing, one dao for each hand.

One measure of the proper length of the sword should be from the hilt in your hand and the tip of the blade at the brow and in some schools, the height of shoulder. Alternatively, the length of the sword should be from the middle of the throat along the length of the outstretched arm. There are also significantly larger versions of dao used for training in some Baguazhang and Taijiquan schools.

Modern wushu competitions incorporate dao routines alongside other weapons-based forms.

See also

References

- Tom 2001, p. 207

- Graff 2002, p. 41

- Lorge 2011, pp. 69-70.

- Lorge 2011, p. 78.

- Lorge 2011, pp. 83-84.

- Lorge 2011, p. 103.

- Tom & Rodell 2005, p. 84

- Hanson 2004

- Tom 2001, p. 207

- Tom 2001, pp. 207–209

- Tom 2001, p. 211

- Tom & Rodell 2005, p. 76

- Tom & Rodell 2005, p. 77

- Tom & Rodell 2005, pp. 77–78

- Tom & Rodell 2005, p. 78

- Tom 2001, p. 211

- Tom & Rodell 2005, pp. 78–79

- Tom & Rodell 2005, pp. 80, 84

- Tom & Rodell 2005, p. 85

- Tom 2001, pp. 209, 218

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dao (sword). |

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-23955-9

- Grancsay, Stephen (1930), "Two Chinese Swords", The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 25 (9): 194–196, doi:10.2307/3255712, JSTOR 3255712

- Hanson, Chris (2004), The Mongol Siege of Xiangyang and Fan-ch'eng and the Song military, retrieved August 23, 2014

- Lorge, Peter A. (2011), Chinese Martial Arts: From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-87881-4

- Tom, Philip M. W. (2001), "Some Notable Sabers of the Qing Dynasty at the Metropolitan Museum of Art", Metropolitan Museum Journal, 36: 11, 207–222, doi:10.2307/1513063, JSTOR 1513063, S2CID 191359442

- Tom, Philip M. W.; Rodell, Scott M. (February 2005), "An Introduction to Chinese Single-Edged Hilt Weapons (Dao) and Their Use in the Ming and Qing Dynasties", Kung Fu Tai Chi: 76–85

- Werner, E. T. C. (1989), Chinese Weapons, Singapore: Graham Brash, ISBN 9971-4-9116-8

External links

- Sword with Scabbard - 17th century example - Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Saber (Peidao) with Scabbard - 18th or 19th century example - Metropolitan Museum of Art