Tachi

A tachi (太刀) was a type of traditionally made Japanese sword (nihonto) worn by the samurai class of feudal Japan. Tachi and katana generally differ in length, degree of curvature, and how they were worn when sheathed, the latter depending on the location of the mei, or signature, on the tang. The tachi style of swords preceded the development of the katana, which was not mentioned by name until near the end of the twelfth century; tachi are known to have been made in the Kotō period, ranging from 900 to 1596.

%2C_A_back_view_of_Onikojima_Yatar%C3%B4_Kazutada_in_armor_holding_a_spear_and_a_severed_head.jpg)

History and description

The production of swords in Japan is divided into specific time periods:

- Jōkotō (ancient swords, until around 900)

- Kotō (old swords from around 900–1596)

- Shintō (new swords 1596–1780)

- Shinshintō (new new swords 1781–1876)

- Gendaitō (modern swords 1876–1945)[1]

- Shinsakutō (newly made swords 1953–present)[2]

Authentic tachi were forged during the Kotō period, before 1596.[3] The tachi preceded the katana; the latter was not mentioned by name to indicate a blade distinct from a tachi until near the end of the twelfth century.[4] With a few exceptions, katana and tachi can be distinguished from each other if signed by the location of the signature (mei) on the tang. In general the signature should be carved into the side of the tang that would face outward when the sword was worn on the wielder's left waist. Since a tachi was worn cutting edge down, and the katana was worn cutting edge up the mei would be in opposite locations on the tang of both types of swords.[5]

An authentic tachi that was manufactured in the correct time period had an average cutting edge length (nagasa) of 70–80 cm (27 9⁄16–31 1⁄2 in) and compared to a katana was generally lighter in proportion to its length, had a greater taper from hilt to point, was more curved and had a smaller point area.[6]

Unlike the traditional manner of wearing the katana, the tachi was worn hung from the belt with the cutting-edge down,[7] and was most effective when used by cavalry.[8] Deviations from the average length of tachi have the prefixes ko- for "short" and ō- for "great, large" attached. For instance, tachi that were shōtō and closer in size to a wakizashi were called kodachi. The longest tachi (considered a 15th-century ōdachi) in existence is more than 3.7 metres (12 ft) in total length with a 2.2 metres (7 ft 3 in) blade, but believed to be ceremonial. In the late 1500s and early 1600s many old surviving tachi blades were converted into katana by having their original tangs cut (o-suriage), which meant the signatures were removed from the swords.[9]

For a sword to be worn in "tachi style" it needed to be mounted in a tachi koshirae. The tachi koshirae had two hangers (ashi) which allowed the sword to be worn in a horizontal position with the cutting edge down.[10] A sword not mounted in a tachi koshirae could be worn tachi style by use of a koshiate, a leather device which would allow any sword to be worn in the tachi style.[11]

Use

According to author Karl F. Friday, before the 13th century there are no written references or drawings etc. that show swords of any kind were actually used while on horseback.[12]

The uchigatana was derived from the tachi and was the predecessor to the katana as the battlesword of feudal Japan's bushi (warrior class), and as it evolved into the later design, the tachi and the uchigatana were often differentiated from each other only by how they were worn, the fittings for the blades, and the location of the signature (mei).

The Mongol invasions of Japan facilitated a change in the designs of Japanese swords. It turned out that the tachi that samurai had used until then had a thick and heavy blade, which was inconvenient to fight against a large number of enemies in close combat. Also, because Tachi until then had been made with emphasis on hardness and lacked flexibility, it was easy to break or chip the blade, and it turned out to be difficult to regrind when the blade was chipped. In response to this, a new method of manufacturing Japanese swords was developed, and an innovative sword of the Sōshū school was born. The swordsmiths at the Sōshū school combined hard and soft steel to make blades, and by optimizing the temperature and timing of heating and cooling the blades, they realized stronger blades. Sōshū school tachi and katana are light because the width from the blade to the ridge side is wide but the cross section is thin, and they are excellent in penetrating ability because the whole curve is gentle and the tip is long and straight. The most famous swordsmith in the Sōshū school is Masamune.[13]

In later Japanese feudal history, during the Sengoku and Edo periods, certain high-ranking warriors of what became the ruling class would wear their sword tachi-style (edge-downward), rather than with the scabbard thrust through the belt with the edge upward.[14]

With the rising of statism in Shōwa Japan, the Imperial Japanese Army and the Imperial Japanese Navy implemented swords called shin and kaiguntō, which were worn tachi style (cutting edge down).[15]

Gallery

Okanehira, by Kanehira. Ko-Bizen (old Bizen) school. 12th century, Heian period, National Treasure, Tokyo National Museum. Okanehira, together with Dojikiri, is considered one of the best Japanese swords in terms of art and is compared to the yokozuna (the highest rank of a sumo wrestler) of Japanese swords.[16]

Okanehira, by Kanehira. Ko-Bizen (old Bizen) school. 12th century, Heian period, National Treasure, Tokyo National Museum. Okanehira, together with Dojikiri, is considered one of the best Japanese swords in terms of art and is compared to the yokozuna (the highest rank of a sumo wrestler) of Japanese swords.[16] Dojikiri, by Yasutsuna. Ko-Hōki (old Hōki) school. 12th century, Heian period, National Treasure, Tokyo National Museum. This sword is one of the Five Swords Under Heaven. (天下五剣 Tenka Goken)

Dojikiri, by Yasutsuna. Ko-Hōki (old Hōki) school. 12th century, Heian period, National Treasure, Tokyo National Museum. This sword is one of the Five Swords Under Heaven. (天下五剣 Tenka Goken)_tachi_tsuka.jpg) Close up view of an antique tachi hilt. One of the "ashi" (sword hanger) can be seen.

Close up view of an antique tachi hilt. One of the "ashi" (sword hanger) can be seen. Tachi by Bizen Osafune Sukesada and koshirae, on display at the British museum.

Tachi by Bizen Osafune Sukesada and koshirae, on display at the British museum. Tachi "kissaki" (blade tip), Bizen school, signed "Tachimei, Bizen no Kuni Osafune Yoshigake"; Nambokucho era (14th century).

Tachi "kissaki" (blade tip), Bizen school, signed "Tachimei, Bizen no Kuni Osafune Yoshigake"; Nambokucho era (14th century). Tachi forged in 1997 by Matsuda Tsuguyasu, koshirae made in 1999 by Takeyama. Copy of Heian era sword (11th century). Galley Dutta, Geneva.

Tachi forged in 1997 by Matsuda Tsuguyasu, koshirae made in 1999 by Takeyama. Copy of Heian era sword (11th century). Galley Dutta, Geneva..png) Various types of "koshiate", a device used to carry a sword in the tachi style (cutting edge down).

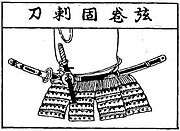

Various types of "koshiate", a device used to carry a sword in the tachi style (cutting edge down). Line drawing showing the correct method of wearing a tachi while in armour.

Line drawing showing the correct method of wearing a tachi while in armour.

See also

- Japanese sword

- Katana

- Uchigatana

- Tenka-Goken - five best swords in Japan. All of the five are classified as tachi.

References

- Clive Sinclaire (1 November 2004). Samurai: The Weapons and Spirit of the Japanese Warrior. Lyons Press. pp. 40–58. ISBN 978-1-59228-720-8.

- トム岸田 (24 September 2004). 靖国刀. Kodansha International. p. 42. ISBN 978-4-7700-2754-2.

- Nagayama, Kōkan (1997). The Connoisseur's Book of Japanese Swords. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2071-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link), page 48

- Turnbull, Stephen (8 February 2011). Katana: The Samurai Sword. Osprey Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-84908-658-5.

- 土子, 民夫; 三品, 謙次 (May 2002). 日本刀21世紀への挑戦. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2854-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link), page 30

- 寒山, 佐藤 (1983). The Japanese Sword. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-0-87011-562-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link), page 15

- Nippon-tô: the Japanese sword, Author Inami Hakusui, Publisher Cosmo, 1948, Original from the University of Michigan, Digitized May 27, 2009 P.160

- "A distinguished collection of arms and armor on permanent display", Issue 4 of Bulletin, Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History History Division, Ward Ritchie Press, 1969. Original from the University of Virginia, Digitized Aug 13, 2010 P.120

- The connoisseur's book of Japanese swords, Author Kōkan Nagayama, Edition illustrated, Publisher Kodansha International, 1998, ISBN 4-7700-2071-6, ISBN 978-4-7700-2071-0 P.48

- Art of the samurai: Japanese arms and armor, 1156-1868, Authors Morihiro Ogawa, Kazutoshi Harada, Publisher Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009, ISBN 1-58839-345-3, ISBN 978-1-58839-345-6 P.193

- Pauley's Guide - A Dictionary of Japanese Martial Arts and Culture, Author Daniel C. Pauley, Publisher Samantha Pauley, 2009, ISBN 0-615-23356-2, ISBN 978-0-615-23356-7 P.91

- P.84

- 五箇伝(五ヵ伝、五ヶ伝) Touken world

- Kapp, Leon; Hiroko Kapp; Yoshindo Yoshihara (1987). The Craft of the Japanese Sword. Japan: Kodansha International. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-87011-798-5.

- The Japanese Army 1931-42, Volume 1 of The Japanese Army, 1931-45, Author Philip S. Jowett, Publisher Osprey Publishing, 2002, ISBN 1-84176-353-5, ISBN 978-1-84176-353-8 P.41

- 「日本刀」の文化的な価値を知っていますか Toyo keizai, August 2 2017

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to tachi. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nihonto. |