Keffiyeh

The keffiyeh or kufiya (Arabic: كُوفِيَّة kūfiyyah, meaning "from the city of Kufa"[1] (الْكُوفَة); plural كُوفِيَّات kūfiyyāt), also known as a ghutrah (غُترَة), shemagh (شُمَاغ šumāġ), ḥaṭṭah (حَطَّة), mashadah (مَشَدَة), chafiye, dastmal yazdi (Persian: دستمال یزدی, Kurdish: دەستمال یەزدی destmal yezdî) or cemedanî (Kurdish: جەمەدانی), is a traditional Arabian headdress, or what is sometimes called a habit, that originated in the Arabian Peninsula, and is now worn throughout the Middle-East region. It is fashioned from a square scarf, and is usually made of cotton.[2] The keffiyeh is commonly found in arid regions, as it provides protection from sunburn, dust and sand. Toward the end of the 1980s, the keffiyeh became a fashion accessory in the United States and, during the early 2000s it became very popular among teenagers in Tokyo, Japan, where it is often worn with camouflage-style clothing.

.jpg)

Varieties and variations

During his sojourn with the Marsh Arabs of Iraq, Gavin Young noted that the local sayyids—"venerated men accepted [...] as descendants of the Prophet Muhammad and Ali ibn Abi Talib"—wore dark green keffiyeh (cheffiyeh) in contrast to the black-and-white checkered examples typical of the area's inhabitants.[3]

Many Palestinian keffiyehs are a mix of cotton and wool, which facilitates quick drying and, when desired, keeping the wearer's head warm. The keffiyeh is usually folded in half (into a triangle) and the fold worn across the forehead. Often, the keffiyeh is held in place by a circlet of rope called an agal (Arabic: عقال, ʿiqāl). Some wearers wrap the keffiyeh into a turban, while others wear it loosely draped around the back and shoulders. A taqiyah is sometimes worn underneath the keffiyeh; in the past, it has also been wrapped around the rim of a fez. The keffiyeh is almost always of white cotton cloth, but many have a checkered pattern in red or black stitched into them. The plain white keffiyeh is most popular in the Arab states of the Persian Gulf—in Kuwait and Bahrain to the exclusion of almost any other style. The keffiyeh is worn by men of all ages, whether on the head or around the shoulders.

.jpg)

In Jordan, the red-and-white keffiyeh is strongly associated with the country and its heritage, because the red color was introduced by the Jordanian Bedouins under British rule, where it is known as the shemagh mhadab. The Jordanian keffiyeh has decorative cotton or wool tassels on the sides; the bigger these tassels, the greater the garment's supposed value and the status of the person wearing it. It has long been worn by Bedouins and villagers and used as a symbol of honor and/or tribal identification. The tasseled red-and-white Jordanian shemagh is much thicker than the untasseled red-and-white shemagh seen in Persian Gulf countries.

In Egypt, the keffiyeh and the agal is worn by Bedouins specially in the Sinai Peninsula. It is also sometimes tied into a turban in varying styles.

In Yemen, the keffiyeh is used extensively in both red-white and black-white pattern. It spread during 1948 through Palestinian refugees.

In Malaysia, the keffiyeh has been worn by Muslim women as part of hijab fashion and during the Palestinian struggle against Israel. Many Malaysians wore it to show solidarity for Palestine.

Also in Indonesia the people used the keffiyeh to show their solidarity with the Palestinians.[4]

In Turkey it was forbidden to wear a keffiyeh because it was seen as evidence of support of the PKK.[5]

The keffiyeh, especially the all-white keffiyeh, is also known as the ghutrah. This is particularly common in the Arabian Peninsula, where the optional skullcap is called a keffiyeh. The garment is also known in some areas as the ḥaṭṭah.

Roughly speaking:

Ordinary keffiyeh

A piece of white/orange/black cloth made from wool and cotton, worn primarily by Palestinians.

Shalls/Musar

A traditional scarf originated from Yemen, usually made of cotton or flax and decorated with many colors, but usually red and white; worn primarily by Yemen, & Oman.

Shemagh

A plain piece of cloth worn by the Arabian Gulf.

Dastmaal Yazdi

.jpg)

A traditional scarf in Iran, originally from the Yazd region of Iran.

Chafiyeh

A style of keffiyeh that originated in Iran, based on the Iranian Dastmaal Yazdi with influences from the Palestinian Keffiyeh. Often worn by Shi'a Muslims in Iran as well as Iraq and Lebanon to express support for Shi'a Political parties. The scarf gained popularity during the Iran-Iraq war as a sign of Shi'a resistance against Saddam. The Chafiyeh is also worn by Basij members of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, Hezbollah, as well as occasionally by members of Iraq's Popular Mobilization Forces, but also by ordinary Shia religious pilgrims not affiliated with any political group.

Ghutrah

A piece of white cloth made of cotton mild, worn in western Iraq and by the Arabs of the Arabian Gulf states.

Rezza

It is worn by inhabitants of North Africa.

Palestinian national symbol

Traditionally worn by Palestinian farmers, the keffiyeh became worn by Palestinian men of any rank and became a symbol of Palestinian nationalism during the Arab Revolt of the 1930s.[6][7] Its prominence increased during the 1960s with the beginning of the Palestinian resistance movement and its adoption by Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat.[6]

.jpg)

The black-and-white fishnet pattern keffiyeh would later become Arafat's iconic symbol, and he would rarely be seen without it; only occasionally would he wear a military cap, or, in colder climates, a Russian-style ushanka hat. Arafat would wear his keffiyeh in a semi-traditional way, wrapped around his head via an agal. He also wore a similarly patterned piece of cloth in the neckline of his military fatigues. Early on, he had made it his personal trademark to drape the scarf over his right shoulder only, arranging it in the rough shape of a triangle, to resemble the outlines of historic Palestine. This way of wearing the keffiyeh became a symbol of Arafat as a person and political leader, and it has not been imitated by other Palestinian leaders.

Another Palestinian figure associated with the keffiyeh is Leila Khaled, a female member of the armed wing of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. Several photographs of Khaled circulated in the Western newspapers after the hijacking of TWA Flight 840 and the Dawson's Field hijackings. These photos often included Khaled wearing a keffiyeh in the style of a Muslim woman's hijab, wrapped around the head and shoulders. This was unusual, as the keffiyeh is associated with Arab masculinity, and many believe this to be something of a fashion statement by Khaled, denoting her equality with men in the Palestinian armed struggle.

The colors of the stitching in a keffiyeh are also vaguely associated with Palestinians' political sympathies. Traditional black and white keffiyehs became associated with Fatah. Later, red and white keffiyehs were adopted by Palestinian Marxists, such as the PFLP.[8]

The color symbolism of the scarves is by no means universally accepted by all Palestinians or Arabs. Its importance should not be overstated, as the scarves are used by Palestinians and Arabs of all political affiliations, as well as by those with no particular political sympathies.

Symbol of Palestinian solidarity

The black and white chequered keffiyeh has become a symbol of Palestinian nationalism, dating back to the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine. Outside of the Middle East and North Africa, the keffiyeh first gained popularity among activists supporting the Palestinians in the conflict with Israel.

The wearing of the keffiyeh often comes with criticism from various political factions in the ongoing Israeli–Palestinian conflict. The slang "keffiyeh kinderlach" refers to young Jews, particularly college students, who sport a keffiyeh around the neck as a political/fashion statement. This term may have first appeared in print in an article by Bradley Burston in which he writes of "the suburban-exile kaffiyeh kinderlach of Berkeley, more Palestinian by far than the Palestinians" in their criticism of Israel. European activists have also worn the keffiyeh.[9][10]

While Western protesters wear differing styles and shades of keffiyeh, the most prominent is the black-and-white keffiyeh. This is typically worn around the neck like a neckerchief, simply knotted in the front with the fabric allowed to drape over the back. Other popular styles include rectangular-shaped scarves with the basic black-and-white pattern in the body, with the ends knitted in the form of the Palestinian flag. Since the Al-Aqsa Intifada, these rectangular scarves have increasingly appeared with a combination of the Palestinian flag and Al-Aqsa Mosque printed on the ends of the fabric.

Production

Today, this symbol of Palestinian identity is now largely imported from China. With the scarf's growing popularity in the 2000s, Chinese manufacturers entered the market, driving Palestinians out of the business.[11] In 2008, Yasser Hirbawi, who for five decades had been the only Palestinian manufacturer of keffiyehs, is now struggling with sales. Mother Jones wrote, "Ironically, global support for Palestinian-statehood-as-fashion-accessory has put yet another nail in the coffin of the Occupied Territories' beleaguered economy."[11]

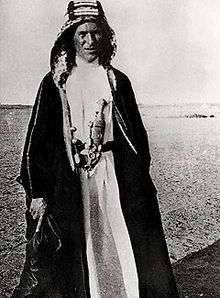

Westerners in keffiyeh

British Colonel T. E. Lawrence (better known as Lawrence of Arabia) was probably the best-known Western wearer of the keffiyeh and agal during his involvement in the Arab Revolt in World War I. This image of Lawrence was later popularized by the film epic about him, Lawrence of Arabia, in which he was played by Peter O'Toole.

The 1920s silent-film era of American cinema saw studios take to Orientalist themes of the exotic Middle East, possibly due to the view of Arabs as part of the Allies of World War I, and keffiyehs became a standard part of the theatrical wardrobe. These films and their male leads typically had Western actors in the role of an Arab, often wearing the keffiyeh with the agal (as with The Sheik and The Son of the Sheik, starring actor Rudolph Valentino).

Erwin Rommel also commonly wore a keffiyeh during the Western Desert Campaign for practical reasons.

Fashion trend

As with other articles of clothing worn in wartime, such as the T-shirt, fatigues and khaki pants, the keffiyeh has been seen as chic among non-Arabs in the West. Keffiyehs became popular in the United States in the late 1980s, at the start of the First Intifada, when bohemian girls and punks wore keffiyehs as scarves around their necks.[12][6] In the early 2000s, keffiyehs were very popular among youths in Tokyo, who often wore them with camouflage clothing.[12] The trend recurred in the mid-2000s in the United States,[12][6] Europe,[6] Canada and Australia,[13][14] when the keffiyeh became popular as a fashion accessory, usually worn as a scarf around the neck in hipster circles.[12][6] Stores such as Urban Outfitters and TopShop stocked the item (however, after some controversy over the retailer's decision to label the item "anti-war scarves" Urban Outfitters pulled it).[6] In spring 2008, keffiyehs in colors like purple and mauve were given away in issues of fashion magazines in Spain and France. In UAE, males are inclining towards more western headgear while the women are developing preferences for dupatta—the traditional head cover of the Indian subcontinent.[15] The appropriation of the keffiyeh as a fashion statement by non-Arab wearers separate from its political and historical meaning has been the subject of controversy in recent years. While it is worn often as a symbol of solidarity with the Palestinian struggle, the fashion industry has disregarded its significance by using its pattern and style in day-to-day clothing design. For example, in 2016 Topshop released a romper with the Keffiyeh print, calling it a "scarf playsuit". This led to accusations of cultural appropriation and Topshop eventually pulled the item from their website[16]

Gallery

.jpg) Iranian children wearing the keffiyeh during a religious gathering

Iranian children wearing the keffiyeh during a religious gathering U.S. Marine wearing a shemagh at the Afghanistan–Pakistan border

U.S. Marine wearing a shemagh at the Afghanistan–Pakistan border

See also

- Aghal, Arabian headdress

- Bisht, Arabian cloak

- Cap

- Gamcha, scarf from the Indian subcontinent

- Gingham, scarf from Malaysia

- ʿEmamah, Arabian turban

- Krama, Cambodian scarf

- List of headgear

- Litham, Arabian headdress

- Sudra (headdress), Jewish scarf

- Tagelmust, Berber scarf

- Tallit, Jewish shawl

- Thawb, Arabian garment

- Balaclava

References

- Ali, Syed Ameer (1924). A Short History Of The Saracens. Routledge. pp. 424–. ISBN 978-1-136-19894-6.

Kufa was famous for its silk and half-silk kerchiefs for the head, which are still used in Western Asia and known as Kuffiyeh.

- J. R. Bartlett (19 July 1973). The First and Second Books of the Maccabees. CUP Archive. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-521-09749-9. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

traditional Jewish head-dress was either something like the Arab's Keffiyeh (a cotton square folded and wound around a head) or like a turban or stocking cap

- Young, Gavin (1978) [First published by William Collins & Sons in 1977]. Return to the Marshes. Photography by Nik Wheeler. Great Britain: Futura Publications. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0-7088-1354-2.

There was a difference here for nearly all of them wore dark green kefiyahs (or cheffiyeh) (headcloths) instead of the customary black and white check ones. By that sign we could tell that they were sayyids, like the sallow-faced man at Falih's.

- Times, Asia. "Asia Times | Indonesia shows its solidarity for the Palestinian cause | Article". Asia Times. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- Uche, Onyebadi (14 February 2017). Music as a Platform for Political Communication. IGI Global. p. 214. ISBN 9781522519874.

- Kim, Kibum. "Where Some See Fashion, Others See Politics" The New York Times (11 February 2007).

- Torstrick, Rebecca (2004). Culture and Customs of Israel. Greenwood. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-313-32091-0.

- Binur, Yoram (1990). My Enemy, My Self. Penguin. p. xv.

- Tipton, Frank B. (2003). A History of Modern Germany Since 1815. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 598. ISBN 0-8264-4910-7.

- Mudde, Cas (2005). Racist Extremism in Central and Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 0-415-35594-X.

- Sonja Sharp (22 June 2009). "Your Intifada: Now Made in China!". Mother Jones.

- Nina (15 February 2005). "Checkered Past: Arafat's trademark scarf is now military chic". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008.

- Arjun Ramachandran (30 May 2008). "Keffiyeh kerfuffle hits Bondi bottleshop". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 29 August 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- Arjun Ramachandran (29 May 2008). "Celebrity chef under fire for 'jihadi chic'". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. Archived from the original on 21 September 2011. Retrieved 24 September 2013.

- "What do Arabs wear on their heads". UAE Style Magazine.

- "Topshop pulls 'keffiyeh playsuit' after row over cultural theft". middleeasteye.net. Retrieved 1 September 2017.

Further reading

- Philippi, Dieter (2009). Sammlung Philippi – Kopfbedeckungen in Glaube, Religion und Spiritualität. St. Benno Verlag, Leipzig. ISBN 978-3-7462-2800-6.

- Jastrow, Marcus (1926). Dictionary of Targumim, Talmud and Midrashic Literature. ISBN 978-1-56563-860-0. The lexicon includes more references explaining what a sudra is on page 962.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Keffiyeh. |

- "The Keffiyeh and the Arab Heartland" from About.com

- "Saudi Aramco World: The dye that binds" by Caroline Stone

- More references about a sudra on page 962 from Jastrow Dictionary Online

- Modern Chronology of the Keffiyah Kraze from Arab American blog Kabobfest

- Che Couture Gives way to Kurds' Puşi Chic by Işıl Eğrikavuk, Hurriyet

- Palestinian Keffiyeh outgrows Mideast conflict

- Last factory in Palestine produces Kuffiyeh

- Hirbawi: The Only Original Kufiya Made in Palestine