Rouran Khaganate

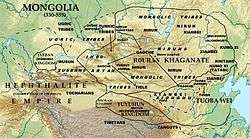

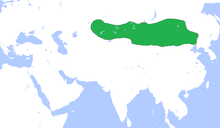

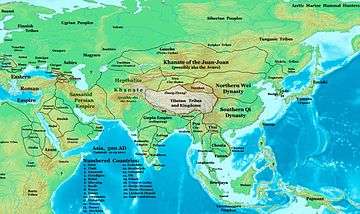

The Rouran Khaganate (Chinese: 柔然; pinyin: Róurán),[3] was a tribal confederation and later state founded by a people of Proto-Mongolic Donghu origin.[4] The Rouran supreme rulers are noted for being the first to use the title of "khagan", having borrowed this popular title from the Xianbei.[5] The Rouran Khaganate lasted from the late 4th century until the middle 6th century, when they were defeated by a Göktürk rebellion which subsequently led to the rise of the Turks in world history.

Rouran Khaganate | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 330 AD–555 AD | |||||||||||||

Rouran Khaganate in Central Asia | |||||||||||||

| Status | Khanate | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Mumo city, Orkhon River, Mongolia | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Rouran Mongolian Chinese | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Tengrism Shamanism Buddhism | ||||||||||||

| Khagan | |||||||||||||

• 330 AD | Yujiulü Mugulü | ||||||||||||

• 555 AD | Yujiulü Dengshuzi | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Kurultai | ||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||

• Established | 330 AD | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 555 AD | ||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||

| 405[1][2] | 2,800,000 km2 (1,100,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | China Kazakhstan Mongolia Russia | ||||||||||||

| Rouran | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 柔然 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Ruru or Ruanruan | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 蠕蠕 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Ruru | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 茹茹 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Ruirui | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 芮芮 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Rouru or Rouruan | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 蝚蠕 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Tantan | |||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 檀檀 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| History of Mongolia | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ancient period

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval period

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Modern period

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Their Khaganate overthrown, some Rouran remnants possibly became Tatars[6][7] while others migrated west and became the Pannonian Avars (known by such names as Varchonites or Pseudo Avars), who settled in Pannonia (centred on modern Hungary) during the 6th century.[8] However, this Rouran-Avars link remains a controversial theory. The Avars were pursued into the Byzantine Empire by the Göktürks, who referred to the Avars as a slave or vassal people, and requested that the Byzantines expel them. Other theories instead link the origins of the Pannonian Avars to peoples such as the Uar.

Name

Nomenclature

Róurán 柔然 is a Classical Chinese transcription of the endonym of the confederacy. 蠕蠕 Ruǎnruǎn ~ Rúrú (Weishu), however, was used in Tuoba-Xianbei sources such as orders given by Emperor Taiwu of Northern Wei. It meant something akin to "wriggling worm" and was used in a derogatory sense.[9] Other transcriptions are 蝚蠕 Róurú ~ Róuruǎn (Jinshu); 茹茹 Rúrú (Beiqishu, Zhoushu, Suishu); 芮芮 Ruìruì (Nanqishu, Liangshu, Songshu), 大檀 Dàtán and 檀檀Tántán (Songshu).

Mongolian Sinologist Sühe Baatar suggests Nirun Нирун as the modern Mongolian term for the Rouran, as Нирун superficially resembles reconstructed Chinese forms beginning with *ń- or *ŋ-. Rashid-al-Din Hamadani recorded Niru'un and Dürlükin as two divisions of the Mongols.[10]

Etymology

Klyastorny reconstructed the ethnonym behind the Chinese transcription 柔然 Róurán (LHC: *ńu-ńan; EMC: *ɲuw-ɲian > LMC: *riw-rian) as *nönör and compares it to Mongolic нөкүр nökür "friend, comrade, companion" (Khalkha нөхөр nöhör). According to Klyashtorny, *nönör denotes "stepnaja vol'nica" "a free, roving band in the steppe, the 'companions' of the early Rouran leaders." In early Mongol society, a nökür was someone who had left his clan or tribe to pledge loyalty to and serve a charissmatic warlord; if this derivation were correct, Róurán 柔然 was originally not an ethnonym, but a social term referring the dynastic founder's origins or the core circle of companions who helped him build his state.[11]

However, Golden identifies philological problems: the ethnonym should have been *nöŋör to be cognate to nökür, & possible assimilation of -/k/- to -/n/- in Chinese transcription needs further linguistic proofs. Even if 柔然 somehow transmitted nökür, it more likely denoted the Rouran's status as the subjects of the Tuoba. Before being used as an ethnonym, Rouran had originally been the byname of chief Cheluhui (车鹿会), possibly denoting his status "as a Wei servitor".[12]

History

Origin

Primary Chinese-language sources Songshu and Liangshu connected Rourans to the earlier Xiongnu (of unknown ethnolinguistic affiliation) while Weishu traced the Rouran's origins back to the Donghu,[13] generally agreed to be Proto-Mongols.[14] Xu proposed that "the main body of the Rouran were of Xiongnu origin" and Rourans' descendants, namely Da Shiwei (aka Tatars), contained Turkic elements, besides Mongolic Xianbei.[6] Even so, the Xiongnu's language is still unknown[15] and Chinese historians routinely ascribed Xiongnu origins to various nomadic groups, yet such ascriptions do not necessarity indicate the subjects' exact origins: for examples, Xiongnu ancestry was ascribed to Turkic-speaking Göktürks and Tiele as well as Para-Mongolic-speaking Kumo Xi and Khitans.[16]

Kwok Kin Poon additionally proposes that the Rouran were descended specifically from Donghu's Xianbei lineage,[17] i.e. from Xianbei who remained in the eastern Eurasian Steppe after most Xianbei had migrated south and settled in Northern China.[18] Genetic testings on Rourans' remains suggested Donghu-Xianbei paternal genetic contribution to Rourans.[19]

Khaganate

The founder of the Rouran Khaganate, Yujiulu Shelun, was descended from slaves of the Xianbei whose women were commonly taken as wives or concubines. In fact the name Rouran itself as used by the Xianbei means something akin to "wriggling worms". After the Xianbei migrated south and settled in Chinese lands during the late 3rd century AD, the Rouran made a name for themselves as fierce warriors. However they remained politically fragmented until 402 AD when Shelun gained support of all the Rouran chieftains and united the Rouran under one banner. Immediately after uniting, the Rouran entered a perpetual conflict with Northern Wei, beginning with a Wei offensive that drove the Rouran from the Ordos region. The Rouran expanded westward and defeated the neighboring Tiele people and expanded their territory over the Silk Roads, even vassalizing the Hephthalites which remained so until the beginning of the 5th century.[20][21] The Hepthalites migrated southeast due to pressure from the Rouran and displaced the Yuezhi in Bactria, forcing the them to migrate further south. Despite the conflict between the Hephthalites and Rouran, the Hephthalites borrowed much from their eastern overlords, in particular the title of "Khan" which was first used by the Rouran as a title for their rulers.[21]

In 424, the Rouran invaded Northern Wei but were repulsed.[22]

In 429, Northern Wei launched a major offensive against the Rouran and killed a large number of people.[20]

The Chinese are foot soldiers and we are horsemen. What can a herd of colts and heifers do against tigers or a pack of wolves? As for the Rouran, they graze in the north during the summer; in autumn, they come south and in winter raid our frontiers. We have only to attack them in summer in their pasture lands. At that time their horses are useless: the stallions are busy with the fillies, and the mares with their foals. If we but come upon them there and cut them off from their grazing and their water, within a few days they will be either taken or destroyed.[20]

In 434, the Rouran entered a marriage alliance with Northern Wei.[23]

In 443, Northern Wei attacked the Rouran.[20]

In 449, the Rouran were defeated in battle by Northern Wei.[24]

In 456, Northern Wei attacked the Rouran.[20]

In 458, Northern Wei attacked the Rouran.[20]

In 460, the Rouran subjugated the Ashina tribe residing around modern Turpan and resettled them in the Altai Mountains.[25] The Rouran also ousted the previous dynasty of Gaochang and installed Kan Bozhou as its king.[20]

The Rouran Khaganate arranged for one of their princesses, Khagan Yujiulü Anagui's daughter Princess Ruru, to be married to the Han Chinese ruler Gao Huan of the Eastern Wei.[26]

Decline

The Rouran and the Hephthalites had a falling out and problems within their confederation were encouraged by Chinese agents.

In 508, the Tiele defeated the Rouran in battle.

In 516, the Rouran defeated the Tiele.

In 551, Bumin of the Ashina Göktürks quelled a Tiele revolt for the Rouran and asked for a Rouran princess for his service. The Rouran refused and in response Bumin declared independence.[27] Bumin entered a marriage alliance with Western Wei, a successor state of Northern Wei, and attacked the Rouran in 552, killing Yujiulü Anagui. Bumin declared himself Illig Khagan of the Turkic Khaganate after conquering Otuken; Bumin died soon after and his son Issik Qaghan succeeded him. Issik continued attacking the Rouran but died a year later in 553. His brother Muqan Qaghan finished the job and annihilated the Rouran in 555.[27][28]

Tatars

According to Xu (2005), some Rouran remnants fled to the northwest of the Greater Khingan mountain range, and renamed themselves 大檀 Dàtán (MC: *daH-dan) or 檀檀 Tántán (MC: *dan-dan) after Tantan, personal name of a historical Rouran Khagan. Tantan were gradually incorporated into the Shiwei tribal complex and later emerged as Great-Da Shiwei (大室韋) in Suishu.[6] Klyashtorny, apud Golden (2013), reconstructed 大檀 / 檀檀 as *tatar / dadar, "the people who, [Klyashtorny] concludes, assisted Datan in the 420s in his internal struggles and who later are noted as the Otuz Tatar (“Thirty Tatars”) who were among the mourners at the funeral of Bumın Qağan (see the inscriptions of Kül Tegin, E4 and Bilge Qağan, E5)".[29]

Avars

Some scholars claim that the Rouran then fled west across the steppes and became the Avars, though many other scholars contest this claim.[30] The remainder of the Rouran fled into China, were absorbed into the border guards, and disappeared forever as an entity. The last khagan fled to the court of the Western Wei, but at the demand of the Göktürks, Western Wei executed him and the nobles who accompanied him.

Genetics

A genetic study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology in August 2018 examined the remains of a Rouran male buried at the Khermen Tal site in Mongolia. He was found to be a carrier of the paternal haplogroup C2b1a1b and the maternal haplogroup D4b1a2a1. Haplogroup C2b1a1b has also been detected among the Xianbei.[31]

A genetic study published in Scientific Reports in November 2019 examined the remains of a large number of early Avar males.[32] The majority of them were found to be primarily of East Asian origin and to have primarily been carriers of the paternal haplogroup N1a1a1a1a3. If one is to assume that the Avars were descended from the Rouran, the genetic evidence implied that Central Asia was dominated by a Siberian ruling class before the Turkic migrations.[33]

A genetic study published in Scientific Reports in January 2020 examined the remains of twenty-six individuals buried at various elite Avar cemeteries in the Pannonian Basin dated to the 7th century AD. The mtDNA of these Avars belonged mostly to East Asian haplogroups, while the Y-DNA was exclusively of East Asian origin.[34] This evidence corroborated the theory that the Pannonian Avars were descended from the Rouran.[35]

Language

Alexander Vovin (2004, 2010)[36][37] considers the Ruan-ruan language to be an extinct non-Altaic language that is not related to any modern-day language (i.e., a language isolate) and is hence unrelated to Mongolic. Vovin (2004) notes that Old Turkic had borrowed some words from an unknown non-Altaic language that may have been Ruan-ruan. In 2018 Vovin changed his opinion after new evidence was found through the analysis of the Brāhmī Bugut and Khüis Tolgoi inscriptions and suggests that the Ruanruan language was in fact a Mongolic language, close but not identical to Middle Mongolian.[38] Pamela Kyle Crossley (2019) The Rouran language itself has remained a puzzle, and leading linguists consider it a possible isolate.[39]

Rulers of the Rouran

The Rourans were the first people who used the titles Khagan and Khan for their emperors, replacing the Chanyu of the Xiongnu, whom Grousset and others assume to be Turkic.[40]

Tribal chiefs

- Yujiulü Mugulü, 4th century

- Yujiulü Cheluhui, 4th century

- Yujiulü Tunugui, 4th century

- Yujiulü Bati, 4th century

- Yujiulü Disuyuan, 4th century

- Yujiulü Pihouba, 4th century

- Venheti, 4th century[41]

- Yujiulü Mangeti, 4th century

- Yujiulü Heduohan, 4th century

Khagans

| Personal name | Regnal name | Reign | Era names |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yujiulü Shelun | Qiudoufa Khagan (丘豆伐可汗) | 402–410 | |

| Yujiulü Hulü | Aikugai Khagan (藹苦蓋可汗) | 410–414 | |

| Yujiulü Buluzhen | 414 | ||

| Yujiulü Datan | Mouhanheshenggai Khagan (牟汗紇升蓋可汗) | 414–429 | |

| Yujiulü Wuti | Chilian Khagan (敕連可汗) | 429–444 | |

| Yujiulü Tuhezhen | Chu Khagan (處可汗) | 444–464 | |

| Yujiulü Yucheng | Shouluobuzhen Khagan (受羅部真可汗) | 464–485 | Yongkang (永康) |

| Yujiulü Doulun | Fumingdun Khagan (伏名敦可汗) | 485–492 | Taiping (太平) |

| Yujiulü Nagai | Houqifudaikezhe Khagan (侯其伏代庫者可汗) | 492–506 | Taian (太安) |

| Yujiulü Futu | Tuohan Khagan (佗汗可汗) | 506–508 | Shiping (始平) |

| Yujiulü Chounu | Douluofubadoufa Khagan (豆羅伏跋豆伐可汗) | 508–520 | Jianchang (建昌) |

| Yujiulü Anagui | Chiliantoubingdoufa Khagan (敕連頭兵豆伐可汗) | 520–521 | |

| Yujiulü Poluomen | Mioukesheju Khagan (彌偶可社句可汗) | 521–524 | |

| Yujiulü Anagui | Chiliantoubingdoufa Khagan (敕連頭兵豆伐可汗) | 522–552 |

Khagans of West

- Yujiulü Dengshuzi, 555

Khagans of East

- Yujiulü Tiefa, 552–553

- Yujiulü Dengzhu, 553

- Yujiulü Kangti, 553

- Yujiulü Anluochen, 553–554

Rulers family tree

| The family tree of the Khaghans of the Rouran | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

Citations

- Taagepera, Rein (1979). "Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D.". Social Science History. 3 (3/4): 129. doi:10.2307/1170959. JSTOR 170959.

- Turchin, Peter; Adams, Jonathan M.; Hall, Thomas D (December 2006). "East-West Orientation of Historical Empires". Journal of World-Systems Research. 12 (2): 222. ISSN 1076-156X. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- Zhang, Min. "On the Defensive System of Great Wall Military Town of Northern Wei Dynasty" China's Borderland History and Geography Studies, Jun. 2003 Vol. 13 No. 2. Page 15.

- Wei Shou. Book of Wei. vol. 103 "蠕蠕,東胡之苗裔也,姓郁久閭氏" tr. "Rúrú, offsprings of Dōnghú, surnamed Yùjiŭlǘ"

- Vovin, Alexander (2007). "Once again on the etymology of the title qaγan". Studia Etymologica Cracoviensia, vol. 12 (online resource)

- Xu Elina-Qian, Historical Development of the Pre-Dynastic Khitan, University of Helsinki, 2005. p. 179-180

- Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). p. 54-56.

- Findley (2005), p. 35.

- Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). p. 54.

- Golden, Peter B. (2016) "Turks and Iranians: Aspects of Türk and Khazaro-Iranian Interaction" in Turcologica 105. p. 5

- Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). p. 58.

- Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). pp. 54-55.

-

- Pulleyblank, Edwin G. (2000). "Ji 姬 and Jiang 姜: The Role of Exogamic Clans in the Organization of the Zhou Polity", Early China. p. 20

- Lee, Joo-Yup (2016). "The Historical Meaning of the Term Turk and the Nature of the Turkic Identity of the Chinggisid and Timurid Elites in Post-Mongol Central Asia". Central Asiatic Journal 59(1-2): 116.

It is not known which language the Xiongnu spoke.

- Lee, Joo-Yup (2016). "The Historical Meaning of the Term Turk and the Nature of the Turkic Identity of the Chinggisid and Timurid Elites in Post-Mongol Central Asia". Central Asiatic Journal 59(1-2): 105.

- "The Northern Wei state and the Juan-juan nomadic tribe". The University of Hong Kong Scholar hub. Retrieved 16 November 2015.

- Hyacinth (Bichurin), Collection of information on peoples lived in Central Asia in ancient times, 1950. p.209

- Li, Jiawei; et al. (August 2018). "The genome of an ancient Rouran individual reveals an important paternal lineage in the Donghu population". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. American Association of Physical Anthropologists. 166 (4). doi:10.1002/ajpa.23491. PMID 29681138. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

We conclude that F3889 downstream of F3830 is an important paternal lineage of the ancient Donghu nomads. The Donghu‐Xianbei branch is expected to have made an important paternal genetic contribution to Rouran. This component of gene flow ultimately entered the gene pool of modern Mongolic‐ and Manchu‐speaking populations.

- Grousset (1970), p. 67.

- Kurbanov, A. The Hephthalites: Archaeological and historical analysis. PhD dissertation, Free University, Berlin, 2010

- Grousset 1970, p. 61.

- Xiong 2009, p. xcix.

- Xiong 2009, p. c.

- Bregel 2003, p. 14.

- Lee, Lily Xiao Hong; Stefanowska, A. D. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women: Antiquity Through Sui, 1600 B.C.E.-618 C.E. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-4182-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) p. 316.

- Barfield 1989, p. 132.

- Xiong 2009, p. ciii.

- Golden, Peter B. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). p. 54-56.

- "Avars". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- Li et al. 2018, pp. 1, 8-9.

- Neparáczki et al. 2019, pp. 5-6, Figure 4.

- Neparáczki et al. 2019, p. 9. "The Avar group carried predominantly East Eurasian lineages in accordance with their known Inner Asian origin inferred from archaeological and anthropological parallels as well as historical sources. However the unanticipated prevalence of their Siberian N1a Hg-s, sheds new light on their prehistory. Accepting their presumed Rouran origin would implicate a ruling class with Siberian ancestry in Inner Asia before Turkic take-over. The surprisingly high frequency of N1a1a1a1a3 Hg reveals that ancestors of contemporary eastern Siberians and Buryats could give a considerable part the Rouran and Avar elite..."

- Csáky et al. 2020, p. 1.

- Neparáczki et al. 2019, p. 9. "A recent manuscript described 23 mitogenomes from the 7th-8th century Avar elite group5 and found that 64% of the lineages belong to East Asian haplogroups (C, D, F, M, R, Y and Z) with affinities to ancient and modern Inner Asian populations corroborating their Rouran origin."

- Vovin, Alexander 2004. 'Some Thoughts on the Origins of the Old Turkic 12-Year Animal Cycle.' Central Asiatic Journal 48/1: 118–32.

- Vovin, Alexander. 2010. Once Again on the Ruan-ruan Language. Ötüken’den İstanbul’a Türkçenin 1290 Yılı (720–2010) Sempozyumu From Ötüken to Istanbul, 1290 Years of Turkish (720–2010). 3–5 Aralık 2010, İstanbul / 3–5 December 2010, İstanbul: 1–10.

- Vovin, Alexander. "A Sketch of the Earliest Mongolic Language: the Brāhmī Bugut and Khüis Tolgoi Inscriptions". International Journal of Eurasian Linguistics. 1 (1): 162–197. ISSN 2589-8825.

- Crossley, Pamela Kyle (2019). Hammer and Anvil: Nomad Rulers at the Forge of the Modern World. p. 49.

- Grousset (1970), pp. 61, 585, n. 91.

- Grousset (1970), pp. 61, 585, n. 91.

Sources

- Barfield, Thomas (1989), The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, Basil Blackwell

- Bregel, Yuri (2003), An Historical Atlas of Central Asia, Brill

- Csáky, Veronika; et al. (22 January 2020). "Genetic insights into the social organisation of the Avar period elite in the 7th century AD Carpathian Basin". Scientific Reports. Nature Research. 10 (948). doi:10.1038/s41598-019-57378-8. PMC 6976699. PMID 31969576. Retrieved 8 April 2020.

- Findley, Carter Vaughn. (2005). The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516770-8 (cloth); ISBN 0-19-517726-6 (pbk).

- Golden, Peter B.. "Some Notes on the Avars and Rouran", in The Steppe Lands and the World beyond Them. Ed. Curta, Maleon. Iași (2013). pp. 43–66.

- Grousset, René. (1970). The Empire of the Steppes: a History of Central Asia. Translated by Naomi Walford. Rutgers University Press. New Brunswick, New Jersey, U.S.A.Third Paperback printing, 1991. ISBN 0-8135-0627-1 (casebound); ISBN 0-8135-1304-9 (pbk).

- Li, Jiawei; et al. (August 2018). "The genome of an ancient Rouran individual reveals an important paternal lineage in the Donghu population". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. American Association of Physical Anthropologists. 166 (4). doi:10.1002/ajpa.23491. PMID 29681138. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- Neparáczki, Endre; et al. (12 November 2019). "Y-chromosome haplogroups from Hun, Avar and conquering Hungarian period nomadic people of the Carpathian Basin". Scientific Reports. Nature Research. 9 (16569). doi:10.1038/s41598-019-53105-5. PMC 6851379. PMID 31719606. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Map of their empire

- Definition Archived 17 September 2003 at the Wayback Machine

- information about the Rouran Archived 18 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Kradin, Nikolay. "From Tribal Confederation to Empire: the Evolution of the Rouran Society". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae, Vol. 58, No 2 (2005): 149–169.

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2000), Sui-Tang Chang'an: A Study in the Urban History of Late Medieval China (Michigan Monographs in Chinese Studies), U OF M CENTER FOR CHINESE STUDIES, ISBN 0892641371

- Xiong, Victor Cunrui (2009), Historical Dictionary of Medieval China, United States of America: Scarecrow Press, Inc., ISBN 0810860538

External links

.png)