Robinson Crusoé

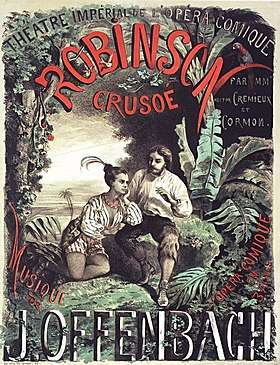

Robinson Crusoé is an opéra comique with music by Jacques Offenbach and words by Eugène Cormon and Hector-Jonathan Crémieux. It premiered in Paris on 23 November 1867.

The writers took the theme from the 1719 novel Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe, though the work owes more to British pantomime than to the book itself. Crusoé leaves his family in England and runs away to sea. He is marooned on an island with only his friend and helper Vendredi (Man Friday) for company. His fiancée and two family servants come to the island in search of him, and after narrow escapes from cannibals and pirates they seize the pirates' ship and set sail for home.

The opera was written for the prestigious Opéra-Comique in Paris, his second work for that theatre, following the unsuccessful Barkouf seven years earlier. The music is on a grander scale than that of most of the composer's earlier works. The opera was well received but ran for only 32 performances. In the 20th century it was not revived until the 1970s (in London) and was not seen again at the Opéra-Comique until 1986.

Background and first production

By the mid-1860s Offenbach had established himself both in Paris and internationally with his opéras bouffes Orphée aux enfers (1858), La belle Hélène (1864), La vie parisienne (1866) and La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein (1867) and many others.[n 1] These were box-office successes in commercial theatres, but the composer's only work for the prestigious state-owned Opéra-Comique, Barkouf (1860), had been a failure, hampered by a plot described by Hector Berlioz as puerile.[n 2] Since then Offenbach had hoped for a triumphant return to the Opéra-Comique, which commissioned a new work from him for the 1867 season.[3] The piece was described as an opéra comique – regarded by the musical establishment as a superior genre to Offenbach's more usual opéra bouffe.[4] Audiences at the Opéra-Comique were more straight-laced than those at the Bouffes-Parisiens, Variétés and other Parisian theatres where Offenbach's works were usually seen,[5] and Offenbach, determined not to alienate them, chose a familiar subject, Robinson Crusoe. It was well known to Parisian audiences from stage adaptations, particularly one by René-Charles Guilbert de Pixérécourt described by Le Figaro as "a happy amalgam of Shakespeare and Daniel de Foë" [sic].[6] In the version by Offenbach's librettists, Eugène Cormon and Hector Crémieux, the first act opened with a reassuringly bourgeois scene: Crusoé senior reading the Bible while his wife busies herself at the spinning wheel.[7] Later in the piece came the expected can-can and the equally required waltz-song.[8]

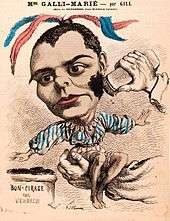

Robinson Crusoé opened at the Opéra-Comique (Salle Favart), on 23 November 1867. Among the cast, playing Vendredi, was Célestine Galli-Marié, later to achieve fame as the first Carmen. The opening night was reported by Le Figaro as a considerable success, with many numbers being encored, but the piece ran for only 32 performances.[9]

Original cast

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 23 November 1867,[10] (Conductor: Jacques Offenbach) |

|---|---|---|

| Robinson Crusoé | tenor | Montaubry |

| Vendredi (Man Friday) | mezzo-soprano | Célestine Galli-Marié |

| Edwige, Robinson's fiancée | soprano | Marie Cico |

| Suzanne, a servant | soprano | Caroline Girard |

| Toby, a servant | tenor | Charles-Auguste Ponchard |

| Jim Cocks,[n 3] a neighbour then cannibal chef | tenor[n 4] | Charles-Louis Sainte-Foy |

| Sir William Crusoé | bass | Crosti |

| Lady Deborah Crusoé | mezzo-soprano | Antoinette-Jeanne Révilly |

| Will Atkins | bass | François Bernard |

| Sailors, natives, etc | ||

Synopsis

Act 1

At the Crusoé family home in Bristol, Lady Crusoé, her niece Edwige and Suzanne, the maid, prepare for Sunday tea, while Sir William pointedly reads aloud the parable of the Prodigal Son from his Bible. Robinson finally arrives disgracefully late, but, a cherished only child, he easily persuades his parents to forgive him. Taking Toby aside, he explains that he has booked passages to South America for them both that very night on the schooner in the harbour. Edwige, realising that she is in love with Robinson, begs him to stay. He is tempted to remain, but she realises she will lose him if he forgoes his dream for her sake. Toby withdraws from the venture – at Suzanne's insistence – but Robinson knows he has to go alone to seek his fortune.

Act 2

Six years later, Robinson is on a desert island at the mouth of the Orinoco, having escaped from pirates who attacked his ship. He has only one companion, Vendredi, whom he earlier rescued from being sacrificed to the gods by the cannibal tribe on the island. Robinson dreams of Edwige, and tries to explain his feelings to Vendredi.

In another part of the island, Edwige, Suzanne and Toby have arrived to look for Robinson. They too have been attacked by and escaped from pirates. Toby and Suzanne are captured by the cannibals, and meet their old Bristol neighbour Jim Cocks. He had run away to sea ten years earlier, and, captured by the cannibals, has become their cook. He cheerfully informs Suzanne and Toby that they will be the cannibals' dinner that evening. At sunset, Edwige is brought in by natives, who believe that she is a white goddess. She is to be sacrificed to their god, Saranha. Vendredi spies all this, and is smitten with Edwige. When the fire is lit, he fires Robinson's pistol, the natives flee, and he rescues Edwige, Suzanne, Toby and Jim Cocks.

Act 3

The next day Robinson discovers Edwige sleeping in his hut and they are blissfully reunited. Vendredi explains that the pirates have left their ship, allowing the English group the chance to seize it and to return to England while the pirates feast and dance. Robinson, feigning insanity, fools the pirates with a story of treasure buried in the jungle and they go off to find it, but are caught by the cannibals. Robinson wields the pirates' guns and the pirates plead to be saved. Robinson agrees, and all set sail for Bristol once again, with the pirate chief, as ship's captain, marrying Robinson and Edwige at sea.

Numbers

Act 1

|

Act 2 Scene 1

Act 2 Scene 2

|

Act 3 Scene 1

Act 3 Scene 2

|

Revivals

In January 1868 Offenbach travelled to Vienna to oversee a production at the Theater an der Wien,[15] and the opera was staged at the Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels the following month.[16] A German version for production in Darmstadt was planned for 1870 but the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War put paid to that.[17] The piece was given in the US by a children's company;[8] a heavily adapted version was presented in Germany as Robinsonade in the 1930s;[8] and the BBC broadcast an abbreviated version of the opera on several occasions in the 1930s and 1940s.[18]

The first professional stage revival in the 20th century was in 1973, at the Camden Festival, London. It was given in an English adaptation by Don White.[8] The cast was: Sir William Crusoe – Wyndham Parfitt; Lady Deborah Crusoe – Enid Hartle; Edwige – Janet Price; Suzanne – Sandra Dugdale; Will Atkins – Wyndham Parfitt; Robinson Crusoe – Ian Caley; Toby – Noel Drennan; Man Friday – Sandra Browne; Jim Cocks – Peter Lyon.[19] The Camden production was licensed to the London Opera Centre in 1974, and presented at Sadler's Wells Theatre, with two different casts. Among the first cast were David Bartleet (Robinson Crusoe), Angela Bostock (Edwige), Ann Murray (Friday), Anna Bernadin (Suzanne), Michael Scott (Toby) and Clive Harré (Jim Cocks). The LOC revived the production in 1976. Marcus Dods conducted both revivals.[20] In 1983 Kent Opera presented the work in a production by Adrian Slack using the Don White English version; Roger Norrington (who "lavished as much care on the score as if it had been by the real Mozart") conducted,[21] and the cast included Neil Jenkins (Robinson); Gerwyn Morgan (Sir William); Vivian Tierney (Edwige); Eirian James (Friday); Eileen Hulse (Suzanne); Andrew Shore (Will Atkins) and Gordon Sandison (Jim Cocks).[22]

Robinson Crusoé was revived at the Opéra-Comique in 1986–1987, in a production directed by Robert Dhéry. There were two casts: Robinson: Gérard Garino, Christian Papis; Sir William Crusoé: Fernand Dumont, Jean-Louis Soumagnas; Toby: Antoine Normand, Christian Papis; Jim Cocks: Jean-Philippe Marlière, Michel Trempont; Atkins: Michel Philippe; Vendredi: Cynthia Clarey, Sylvie Sullé; Edwige: Danielle Borst, Lucia Scappaticci; Suzanne: Eliane Lublin, Marie-Christine Porta; Deborah: Anna Ringart, Hélia T'Hézan. The conductors were Michel Tabachnik and John Burdekin.[23]

Opera della Luna's 1994 production of the work toured and was revived at the Iford Arts Festival in 2004.[9][24] The work was again presented at Sadler's Wells in 1995: British Youth Opera was conducted by Timothy Dean.[25] Ohio Light Opera produced the work in 1996.[9] In London there have been productions by the students of two conservatoires: the Guildhall School of Music and Drama (1988), with Susannah Waters as Edwige,[26] and the Royal College of Music (2019).[9]

Critical reception

Reviewing the original production the critic of Le Figaro, Eugène Tarbé, judged the piece excessively long, with too much music and too much dialogue. He thought the plot predictable and the action held up by too much padding. Tarbé found much to praise among the musical numbers: "a string of happy inspirations, melodies, sometimes joyful and sometimes tender". He thought Edwige's "Conduisez-moi vers celui que j'adore" rather too reminiscent of earlier waltz songs by Offenbach, but thought "Ne le voyez-vous pas?" "a delicious quartet, written in a melodic style, simple and severe at the same time", and singled out among other numbers "Debout, c'est aujourd'hui dimanche", the "Chanson du pot-au-feu" and the overture and entr'actes.[6]

After the first revival, in 1973, the critic Winton Dean wrote that although the piece has some very attractive music:

there is a basic flaw: Offenbach clearly could not decide whether he was writing opéra comique, which aims at genuine, if stylized, sentiment and character, or operetta, which makes no such claim. The heroine is a straight romantic figure, and so to some extent is the hero. The second pair of lovers and Jim Cocks, a pre-Crusoe emigrant to the Orinoco who preferred to be the cannibals' chef (in two senses) rather than their dinner, are pure operetta. The pirates are of the Penzance variety; the cannibals have a Gilbertian relish for their food. Man Friday ... is, if not original, a convincing character in whom comedy, pathos and native good sense are happily blended. He has the two best airs in the score.[27]

In 1974 Andrew Lamb rated Robinson Crusoé "a rewarding score ... the work displays the composer's ability for more ambitious orchestral and vocal writing than usual, and passages of typically racy and tuneful writing alternate with moments of genuine pathos."[28] In Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians Lamb comments that the action "owes as much to the British pantomime version of Defoe as to the novel".[29] Lamb singles out Friday’s song "Tamayo, mon frère" and Edwige’s waltz song "Conduisez-moi vers celui que j'adore" as musical highlights.[29] In 1982, The Musical Times commented, "Crusoe is described as an opéra comique, but the more hectic cheerfulness of opéra-bouffe keeps breaking in. Offenbach's invention is in full flood."[30]

Recordings

WorldCat (at 2019) lists no recordings of the complete opera in French made at any time.[31] A live recording of the 1973 Camden Festival production was published as an LP set by the Unique Opera Records Corporation with a limited release.[19] Opera Rara has published a studio recording of the Don White edition made in London in 1980, conducted by Alun Francis with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and the Geoffrey Mitchell Choir. The cast comprised John Brecknock (Robinson Crusoe), Sandra Browne (Man Friday), Enid Hartle (Lady Deborah Crusoe), Marilyn Hill Smith (Suzanne), Roderick Kennedy (Sir William Crusoe), Yvonne Kenny (Edwige), Alexander Oliver (Toby), Alan Opie (Jim Cocks) and Wyndham Parfitt (Will Atkins).[8]

Edwige's waltz song, "Conduisez-moi vers celui que j'adore", has been recorded by sopranos including Natalie Dessay, Amelia Farrugia, Elizabeth Futral, Sumi Jo and Joan Sutherland.[32]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- Orphée aux enfers is described on its title page as an opéra bouffon; the other three are given the more usual label of "opéra bouffe.[1]

- The plot of Barkouf revolved around the appointment of a dog as governor of an Indian province, and was dismissed by Parisians as "chiennerie" – approximately translated as "a bitch of a piece".[2]

- The character appears to have been called "Jin Cocks" or "Jins Cocks" originally, and is so referred to in French and foreign newspaper reviews of the premiere.[6][11][12] The English journal The Orchestra speculated that the name derived from "gin cocktails".[13] The name is printed as "Jim-Cocks" in the 1867 vocal score published by Brandus and Dufour, Paris.[10]

- Shown in the score as "Trial", a character tenor style named after Antoine Trial.[10][14]

References

- Faris, pp. 240–244

- Traubner, p. 39

- Traubner, p. 55

- Traubner, p. 8; and Bartlet, Elizabeth and Richard Langham Smith. "Opéra comique" Archived 2018-06-03 at the Wayback Machine, Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 19 March 2019.(subscription required)

- Ellis, Katharine. "Paris, 1866: In Search of French Music", Music & Letters, November 2010, p. 547

- Tarbé, Eugène. "Robinson Crusoé", Le Figaro, 25 November 1867, p. 1

- Faris, p. 152

- White, Don (1980). Notes to Opera Rara CD set OR228 OCLC 945449445

- Clarke, Kevin. "Offenbach and Opera Rara" Archived 2018-06-13 at the Wayback Machine, Operetta Research Center, 19 March, 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2019

- Robinson Crusoé vocal score. Retrieved 19 March 2019

- "Robinson Crusoe as an Opera", Daily Alta California, 19 January 1868

- "Shaver Silver on Robinson Offenbach Crusoe", The Musical World, 14 December 1867, p. 854; and "Music", The Pall Mall Gazette, 3 December 1867, p. 10

- "France", The Orchestra, 7 December 1867, p. 166

- Cotte, Roger J.V. "Trial family", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 23 December 2018 (subscription required)

- "Music", The Sunday Times, 26 January 1868, p. 3

- "Music", The Morning Post, 21 February 1868, p. 5

- Sterne, Ashley. "Defoe Defied", Radio Times, 23 April 1937, p. 8

- "Offenbach: Robinson Crusoe", BBC Genome, BBC. Retrieved 19 March 2019

- Shaman et al, p. 68

- "Sadler's Wells – Robinson Crusoe", The Stage, 12 August 1976, p. 12

- Milnes, Rodney. British Opera Diary – Robinson Crusoe; Kent Opera at the Orchard Theatre, Dartford. Opera, January 1984, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 90–91.

- Russell, Clifford. "Neglected Crusoe", The Stage, 10 November 1983, p. 16

- "Robinson Crusoe", MémOpéra, Opéra National de Paris. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- "Theatre Week", The Stage, 9 June 1994, p. 10

- "Sadler's Wells – Robinson Crusoe", The Stage, 28 September 1995, p. 15

- Forbes, Elizabeth. Student Performance – Robinson Crusoe; Guildhall School of Music and Drama. Opera, August 1988, Vol. 39, No. 8, pp. 1012-1013.

- Dean, Winton. "Robinson Crusoe", The Musical Times, May 1973, pp. 508–509

- Lamb, Andrew. "Robinson Crusoe", The Musical Times, June 1974, p. 495

- Lamb, Andrew. "Robinson Crusoe" Archived 2018-06-05 at the Wayback Machine, Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press. Retrieved 19 March 2019. (subscription required)

- Crichton, Ronald. "Robinson Crusoe". The Musical Times, May 1982, p. 340

- "Robinson Crusoe, Offenbach", World Cat. Retrieved 19 March 2019

- "Conduisez-moi vers celui que j'adore", WorldCat. Retrieved 19 March 2019

Sources

- Faris, Alexander (1980). Jacques Offenbach. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-11147-3.

- Shaman, William; William J Collins; Calvin M Goodwin (1999). More EJS: discography of the Edward J. Smith recordings. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-29835-6.

- Traubner, Richard (2016). Operetta: A Theatrical History. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-13892-6.

External links

- Robinson Crusoé: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Ohio Light Opera's Crusoe page