La belle Hélène

La belle Hélène (French pronunciation: [la bɛl elɛn], The Beautiful Helen), is an opéra bouffe in three acts, with music by Jacques Offenbach and words by Henri Meilhac and Ludovic Halévy. The piece parodies the story of Helen's elopement with Paris, which set off the Trojan War.

The premiere was at the Théâtre des Variétés, Paris, on 17 December 1864. The work ran well, and productions followed in three continents. La belle Hélene continued to be revived throughout the 20th century, and has remained a repertoire piece in the 21st.

Background and first performance

By 1864 Offenbach was well established as the leading French composer of operetta. After successes with his early works – short pieces for modest forces – he was granted a licence in 1858 to stage full-length operas with larger casts and chorus. The first of these to be produced, Orphée aux enfers, achieved notoriety and box-office success for its risqué satire of Greek mythology, French musical tradition, and the Second Empire.[1] During the subsequent six years the composer attempted, generally in vain, to emulate this success.[2] In 1864 he returned to classical mythology for his theme. His frequent collaborator, Ludovic Halévy, wrote a sketch for an opera to be called The Capture of Troy (La prise de Troie). Offenbach suggested a collaboration with Hector Crémieux, co-librettist of Orphée, but Halévy preferred a new partner, Henri Meilhac, who wrote much of the plot, to which Halévy added humorous details and comic dialogue.[3][4] The official censor took exception to some of their words for disrespect for Church and state, but an approved text was arrived at.[5]

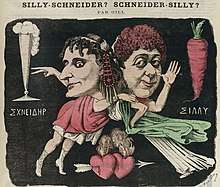

In the Grove essay on the work, Andrew Lamb writes, "As with most of Offenbach’s greatest works, the creation of La belle Hélène seems to have been largely untroubled".[7] Although the writing of the work went smoothly, rehearsals did not. The manager of the Théâtre des Variétés, Théodore Cogniard, was penny-pinching and unsympathetic to Offenbach's taste for lavish staging and large-scale orchestration, and the two leading ladies – Hortense Schneider and Léa Silly – engaged in a running feud with each other. The feud became public knowledge and provoked increasing interest in the piece among Parisian theatregoers.[8]

The opera opened on 17 December 1864. The first night audience was enthusiastic but the reviews were mixed,[n 2] and box-office business was sluggish for a few subsequent performances until supportive reviews by leading writers such as Henri Rochefort and Jules Vallès made their impression on the public, after which the piece drew large audiences from fashionable bohemians as well as respectable citizens from the wealthy arrondissements.[11] It ran through most of 1865 (with a summer break in mid-run),[12] and was replaced in February 1866 with Barbe-bleue, starring the same leading players, except for Silly, with whom Schneider declined ever to appear with again.[13]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 17 December 1864, (Conductor: Jacques Offenbach) |

|---|---|---|

| Agamemnon, King of Kings | baritone | Henri Couder |

| Ménélas, King of Sparta | tenor | Jean-Laurent Kopp |

| Pâris, son of King Priam of Troy | tenor | José Dupuis |

| Calchas, high priest of Jupiter | bass | Pierre-Eugène Grenier |

| Achille, King of Phthiotis | tenor | Alexandre Guyon |

| Oreste, son of Agamemnon | soprano or tenor | Léa Silly |

| Ajax I, King of Salamis | tenor | Edouard Hamburger |

| Second Ajax, King of the Locrians | baritone | M. Andof |

| Philocome, Calchas's attendant | spoken | M. Videix |

| Euthyclès, a blacksmith | spoken | M. Royer |

| Hélène, Queen of Sparta | mezzo-soprano | Hortense Schneider |

| Parthénis, a courtesan | soprano | Mlle. Alice |

| Lœna, a courtesan | mezzo-soprano | Mlle. Gabrielle |

| Bacchis, Helen's attendant | soprano | Mlle. C. Renault |

| Ladies and Gentlemen, Princes, Guards, People, Slaves, Helen’s servants, Mourners of Adonis | ||

Synopsis

- Place: Sparta and the shores of the sea

- Time: Before the Trojan War.

Act 1

Paris, son of Priam, arrives with a missive from the goddess Venus to the high priest Calchas, commanding him to procure for Paris the love of Helen, promised him by Venus when he awarded the prize of beauty to her in preference to Juno and Minerva.

Paris arrives, disguised as a shepherd, and wins three prizes at a "contest of wit" (outrageously silly wordgames) with the Greek kings under the direction of Agamemnon, whereupon he reveals his identity. Helen, who was trying to settle after her youthful adventure and aware of Paris's backstory, decides that fate has sealed her fate. The Trojan prince is crowned victor by Helen, to the disgust of the lout Achilles and the two bumbling Ajaxes. Paris is invited to a banquet by Helen's husband Menelaus, the king of Sparta. Paris has bribed Calchas to "prophesise" that Menelaus must at once proceed to Crete, which he agrees to reluctantly under general pressure.

Act 2

While the Greek kings party in Menelaus's palace in his absence, and Calchas is caught cheating at a board game, Paris comes to Helen at night. After she sees off his first straightforward attempt at seducing her, he returns when she has fallen asleep. Helen has prayed for some appeasing dreams and appears to believe that this is one, and so resists him not much longer. Menelaus unexpectedly returns and finds the two in each other's arms. Helen, exclaiming 'la fatalité, la fatalité', tells him that it is all his fault: A good husband knows when to come and when to stay away. Paris tries to dissuade him from kicking up a row, but to no avail. When all the kings join the scene, berating Paris and telling him to go back where he came from, Paris departs, vowing to return and finish the job.

Act 3

The kings and their entourage have moved to Nauplia for the summer season, and Helen is sulking and protesting her innocence. Venus has retaliated for the treatment meted out to her protégé Paris by making the whole population giddy and amorous, to the despair of the kings. A high priest of Venus arrives on a boat, explaining that he has to take Helen to Cythera where she is to sacrifice 100 heifers for her offences. Menelaus pleads with her to go with the priest, but she refuses initially, saying that it is he, and not she, who has offended the goddess. However, when she realises that the priest is Paris in disguise, she embarks and they sail away together.

Musical numbers

Act 1

- Introduction and chorus

- "Amours divins" – "Divine loves" – Chorus and Helen

- Chœur et Oreste "C'est Parthoénis et Léoena" – "It's Parthoenis and Leoena" – Chorus and Orestes

- Air de Pâris "Au mont Ida" – Air: "Mount Ida" – Paris

- Marche des Rois de la Grèce – March of the Kings of Greece

- Chœur "Gloire au berger victorieux"; "Gloire! gloire! gloire au berger" – "Glory to the victorious shepherd"; "Glory! glory! glory to the shepherd " – Chorus and Helen

Act 2

- Entr'acte

- Chœur "O Reine, en ce jour" – "O Queen, on this day" – Chorus

- Invocation à Vénus – Invocation to Venus – Helen

- Marche de l'oie – The march of the Goose

- Scène du jeu – Scene of the game of "Goose"

- Chœur en coulisses "En couronnes tressons les roses" – "In wreaths braid roses" – Offstage chorus

- Duo Hélène-Pâris "Oui c'est un rêve" – "Yes it's a dream" – Helen and Paris

- "Un mari sage" (Hélène), valse et final: " A moi! Rois de la Grèce, à moi! " – "A wise husband"; waltz and finale: "To me! Kings of Greece, to me!" – Helen; Menelaus

Act 3

- Entr'acte

- Chœur et ronde d'Oreste "Vénus au fond de nos âmes" – "Venus in the depths of our souls" – Chorus and Orestes

- Couplets d'Hélène "Là vrai, je ne suis pas coupable" – Couplets: "There, I'm not guilty" – Helen

- Trio patriotique (Agamemnon, Calchas, Ménélas) – Patriotic Trio – Agamemnon, Calchas, Menelaus

- Chœur "La galère de Cythère", tyrolienne de Pâris "Soyez gais" – "The ship for Cythera"; Tyrolean song: "Be gay" – Chorus and Paris

- Finale – All

Revivals

19th century

La belle Hélène was revived at the Variétés in 1876, 1886 and 1889 starring Anna Judic, in 1890 with Jeanne Granier, and 1899 with Juliette Simon-Girard.[14]

The Austrian premiere was at the Theater an der Wien, as Die schöne Helena, in March 1865. The work was given in Berlin at the Friedrich-Wilhelmstädtisches Theater in May of that year, in Brussels the following month,[15] and in Hungary in March 1866 in German and April 1870 in Hungarian.[14]

In London an adaptation by F. C. Burnand titled Helen, or Taken From the Greek opened in June 1866 at the Adelphi Theatre.[16] The original French version had two productions at the St James's Theatre; the first, in July 1868, starred Schneider as Helen;[17] the second, in July 1873, featured Marie Desclauzas, Mario Widmer and Pauline Luigini.[18] Other English adaptations (including a second one by Burnand) were given at the Gaiety Theatre (1871),[19] the Alhambra Theatre (1873)[19] and the Royalty Theatre (1878).[14]

The first New York production of the opera was given in German at the Stadt Theater, New York, in December 1867; the original French version followed, at the Théâtre Français (March 1868) and an English adaptation by Molyneux St John as Paris and Helen, or The Greek Elopement at the New York Theatre (April 1868). There were further US productions in 1871 (in French) and 1899 (in English), with Lillian Russell as Helen.[14] The Australian premiere was at the Royal Victoria Theatre, Sydney in May 1876.[14] From its Russian premiere in the 1868–69 season in St Petersburg, La belle Hélène became, and remained for a decade, the most popular stage work in Russia. In its first run it played for a record-breaking forty-two consecutive performances.[20]

20th century

Revivals in Paris included those at the Théâtre de la Gaîté-Lyrique (1919), the Théâtre Mogador (1960), Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens (1976) and the Théâtre National de l'Opéra-Comique (1983 and 1985) and the Théâtre de Paris (1986).[14] In 1999 the Aix-en-Provence Festival staged a production by Herbert Wernicke described by Kurt Gänzl as "sadly tawdry and gimmicky ... showing no comprehension of the opéra-bouffe idiom".[15][21]

Max Reinhardt's spectacular adaptation of the work was produced at the Theater am Kurfürstendamm in Berlin in 1931, starring Jarmila Novotna. The score was heavily adapted by Erich Korngold.[15] Reinhard directed his version in England in December 1931, with a text by A. P. Herbert under the title Helen, starring Evelyn Laye.[22] An English version more faithful to Meilhac and Halévy's original was given by Sadler's Wells Opera in 1963 and was revived at the London Coliseum in 1975. Scottish Opera toured the work in the 1990s in a translation by John Wells,[23] and English National Opera (ENO) presented Offenbach's score with a completely rewritten libretto by Michael Frayn as La belle Vivette which ran briefly at the Coliseum in 1995,[24] and was bracketed by Hugh Canning of The Sunday Times with Wernicke's Aix production as "horrors unforgotten".[25]

American productions included those of the New York City Opera (1976) with Karan Armstrong,[14] Ohio Light Opera (1994),[26] and Lyric Opera Cleveland (1996).[27]

21st century

Among revivals in France there have been productions at the Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris (2000 and 2015), the Opéra d'Avignon and Opéra de Toulon (both 2014), the Grand Théâtre de Tours (2015), and the Opéra national de Lorraine (2018).[28] The 2000 Châtelet production, by Laurent Pelly, was presented by ENO at the Coliseum in 2006 with Felicity Lott as Helen.[29] In the US productions have included those by Portland Opera (2001),[30] and Santa Fe Opera starring Susan Graham (2003).[31]

Critical reception

The reviewer in Le Journal amusant thought the piece had all the expected Offenbach qualities: "grace, tunefulness, abandonment, eccentricity, gaiety and spirit. ... Do you like good music of cheerful spirit? Here is! Do you want to laugh and have fun? You will laugh, you will have fun! Do you like to see a battalion of beautiful women? Go to the Variétés! For these reasons and many others, La belle Hélène will have its 100 performances. There is no better party at the theatre." The reviewer commented that the librettists were not at their subtlest in this piece, and had "painted with a broad brush of buffoonery".[32] The British journal The Musical World thought the music "very flimsy and essentially second-rate", and attributed the opera's great success to the popularity of Schneider.[33] The Athenaeum considered the piece grossly indecent.[n 3]

In his 1980 biography of Offenbach, Peter Gammond writes that the music of La belle Hélène is "refined and charming and shows the most Viennese influence". He adds that although it lacks "hit" tunes, it is a cohesive and balanced score, with excellent songs for Helen.[35] But Alexander Faris (1981) writes, "It would be difficult to name an operetta with more good tunes than La belle Hélène (although Die Fledermaus would be a strong contender)".[36] He comments that in this score Offenbach's harmony became more chromatic than it had been in earlier works, and foreshadowed some of Tchaikovsky's harmonic effects. Both writers regard the music more highly than did Neville Cardus, who wrote of this score that Offenbach was not fit for company with Johann Strauss, Auber and Sullivan.[37][n 4] More recently, Rodney Milnes, reviewing the 2000 Châtelet production, wrote, "The whole show is as innocently filthy as only the French can manage. And it is musically superb."[38] In his history of operetta (2003), Richard Traubner writes, "La belle Hélène is more than an elaborate copy of Orphée aux enfers. It transcends the former to even higher Olympian heights in the operetta canon. Its finales are funnier, more elaborate, and involve an even greater use of the chorus; the orchestrations are richer, the tunes more plentiful, and there is a waltz of great grace and beauty in Act II".[39]

Recordings

- Felicity Lott, Yann Beuron, Michel Sénéchal, Laurent Naouri, François le Roux, Marie-Ange Todorovitch. Musical direction Marc Minkowski (version given at the Théâtre du Châtelet in 2000).

- Jessye Norman, John Aler, Charles Burles, Gabriel Bacquier, Jean-Philippe Lafont. Musical direction, Michel Plasson.

- Jane Rhodes, Rémy Corazza, Jacques Martin, Jules Bastin, Michel Trempont, with the Orchestre philharmonique de Strasbourg under Alain Lombard, and the chorus of the Opéra national du Rhin under Gunter Wagner (1978).

- Recordings which appear on operadis-opera-discography.org.uk

See also

- Poire belle Hélène

- Sköna Helena - a 1951 Swedish film

- Libretto in WikiSource (in French)

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- The carrot is an allusion to the song "Vénus aux carottes", by Paul-Léonce Blaquière, with which Silly was associated.[6]

- The vehement hostility of the critic Jules Janin of the Journal des débats had piqued the public's interest in Orphée in 1858 and boosted attendances;[9] he tried to avoid falling into the same trap on this occasion but could not restrain his invective against the "perfidious" Meilhac, "traitor" Halévy and "wretched" Offenbach.[10]

- The magazine's 680-word article denouncing the opera did not at any point mention the composer's name.[34]

- Cardus evidently excepted The Tales of Hoffmann from his strictures: "There was more music in Sullivan's little finger than Offenbach dreamed of in all his life, until at death's door he was inexplicably touched by poetry".[37]

References

- Lamb, Andrew. "Orphée aux enfers", Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2002. Retrieved 14 April 2019. (subscription required)

- Faris, pp. 71, 77, 92 and 110; and Kracauer, p. 242

- Faris, p. 112

- Kracauer, p. 244

- Kracauer, pp. 244–245

- Breckbill, Anita. "André Gill and Musicians in Paris in the 1860s and 1870s: Caricatures in La Lune and L'Éclipse", Music in Art 34, no. 1/2 (2009), pp. 218 and 228

- Lamb, Andrew. "Belle Hélène, La" Grove Music Online, Oxford University Press, 2002. Retrieved 14 April 2019 (subscription required)

- Kracauer, pp 243–244; and Faris, p. 125

- Martinet, p. 50

- Kracauer, p. 246

- Kracauer, p. 249

- Faris, p. 134

- Faris, pp. 138–139

- Gänzl and Lamb, pp. 286–287

- Gänzl, Kurt. "La belle Hélène", Operetta Research Center, 2001. Retrieved 15 April 2019

- "Adelphi Theatre", The Morning Post, 2 July 1866, p. 2

- "St. James's Theatre", The Standard, 13 July 1868, p. 3

- "St. James's Theatre", The Morning Post, 12 July 1873, p. 4

- Gaye, p. 1359

- Senelick, Laurence. "Offenbach and Chekhov; Or, La Belle Yelena", The Theatre Journal 42, no. 4 (1990), pp. 455–467. (subscription required)

- Canning, Hugh. "I love Paris... Opera", The Sunday Times, 5 November 2000, p. 18 (Culture section)

- "Troy Without Tears", The Manchester Guardian, 28 December 1931, p. 11; and "Baroque Treatment of a Classical Theme: Helen! at the Adelphi", Illustrated London News, 6 February 1932, p,. 212

- Hoyle, Martin. "Arts: 'La Belle Helene", The Financial Times, 3 November 1995, p. 13

- Traubner, unnumbered introductory page

- Porter, Andrew. "Helen destroyed: Frayn reduces Offenbach's classical figures to Chippendales and Paris to plaster, The Observer, 17 December 1995, p. 61

- Guregian, Elaine. "Updating 'Helene'", Akron Beacon Journal, 25 June 1994, p. C6

- Rosenberg, Donald. "La Belle Helene A Zany Kickoff for Season", The Plain Dealer, 28 June 1996, p. 1E

- "La belle Hélène", Opera Online. Retrieved 15 April 2019

- Picard, Anna. "A thousand ships? This Helen can’t launch a dozen", The Independent on Sunday, 9 April 2006, p. 19

- McQuillen, James. "'La Belle Helene' -- Funny, Absurd, Satirical", The Oregonian, 11 May 2001, p. 62

- Cantrell, Scott. "Juvenility Impairs 'Hélène': staging is a jumble of dubious jokes and clashing themes", The Dallas Morning News 31 July 2003, p. 9b

- Wolf, Albert. "Chronique Théatrale", Le Journal amusant, 24 December 1864, pp. 6–7

- "Mdlle Schneider", The Musical World, 8 August 1868, p. 549

- "Music and the Drama", The Athenaeum, 18 July 1868, p. 90

- Gammond, p. 81

- Faris, pp. 121–122

- Cardus, Neville. "'Helen!' at the Opera House", The Manchester Guardian, 28 December 1931, p. 11

- Milnes, Rodney. "La Belle Helene", The Times, 3 October 2000, p. T2.22.

- Traubner, p. 43

Sources

- Faris, Alexander (1980). Jacques Offenbach. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-11147-3.

- Gammond, Peter (1980). Offenbach. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-0257-2.

- Gänzl, Kurt; Andrew Lamb (1988). Gänzl's Book of the Musical Theatre. London: The Bodley Head. OCLC 966051934.

- Gaye, Freda (ed) (1967). Who's Who in the Theatre (fourteenth ed.). London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons. OCLC 5997224.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Kracauer, Siegfried (1938). Orpheus in Paris: Offenbach and the Paris of his Time. New York: Knopf. OCLC 639465598.

- Martinet, André (1887). Offenbach: Sa vie et son oeuvre. Paris: Dentu. OCLC 3574954.

- Traubner, Richard (2016) [2003]. Operetta: A Theatrical History (second ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-13892-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to La Belle Hélène. |