Victorien Sardou

Victorien Sardou (/sɑːrˈduː/ sar-DOO, French: [viktɔʁjɛ̃ saʁdu]; 5 September 1831 – 8 November 1908) was a French dramatist.[1] He is best remembered today for his development, along with Eugène Scribe, of the well-made play.[2] He also wrote several plays that were made into popular 19th-century operas such as La Tosca (1887) on which Giacomo Puccini's opera Tosca (1900) is based, and Fédora (1882) and Madame Sans-Gêne (1893) that provided the subjects for the lyrical dramas Fedora (1898) and Madame Sans-Gêne (1915) by Umberto Giordano.

Victorien Sardou | |

|---|---|

Sardou in 1880 | |

| Born | Victorien Léandre Sardou 5 September 1831 |

| Died | 8 November 1908 (aged 77) |

| Occupation | Playwright |

| Nationality | French |

| Period | 19th-century |

| Genre | Well-made play |

Early years

Victorien was born in rue Beautreillis (pronounced [ʁy bo.tʁɛ.ji]), Paris on 5 September 1831. The Sardous were settled at Le Cannet, a village near Cannes, where they owned an estate, planted with olive trees. A night's frost killed all the trees and the family was ruined. Victorien's father, Antoine Léandre Sardou, came to Paris in search of employment. He was in succession a book-keeper at a commercial establishment, a professor of book-keeping, the head of a provincial school, then a private tutor and a schoolmaster in Paris, besides editing grammars, dictionaries and treatises on various subjects. With all these occupations, he hardly succeeded in making a livelihood, and when he retired to his native country, Victorien was left on his own resources. He had begun studying medicine, but had to desist for want of funds. He taught French to foreign pupils: he also gave lessons in Latin, history and mathematics to students, and wrote articles for cheap encyclopaedias.[3]

Career

At the same time he was trying to make headway in the literary world. His talents had been encouraged by an old bas-bleu, Mme de Bawl, who had published novels and enjoyed some reputation in the days of the Restoration, but she could do little for her protégé. Victorien Sardou made efforts to attract the attention of Mlle Rachel, and to win her support by submitting to her a drama, La Reine Ulfra, founded on an old Swedish chronicle. A play of his, La Taverne des étudiants, was produced at the Odéon on 1 April 1854, but met a stormy reception, owing to a rumour that the débutant had been instructed and commissioned by the government to insult the students. La Taverne was withdrawn after five nights. Another drama by Sardou, Bernard Palissy, was accepted at the same theatre, but the arrangement was cancelled in consequence of a change in the management. A Canadian play, Fleur de Liane, would have been produced at the Ambigu but for the death of the manager. Le Bossu, which he wrote for Charles Albert Fechter, did not satisfy the actor; and when the play was successfully produced, the nominal authorship, by some unfortunate arrangement, had been transferred to other men. Sardou submitted to Adolphe Lemoine, manager of the Gymnase, a play entitled Paris à l'envers, which contained the love scene, afterwards so famous, in Nos Intimes. Lemoine thought fit to consult Eugène Scribe, who was revolted by the scene in question.[3]

In 1857, Sardou felt the pangs of actual want, and his misfortunes culminated in an attack of typhoid fever. He was living in poverty and was dying in his garret, surrounded with his rejected manuscripts. A lady who was living in the same house unexpectedly came to his assistance. Her name was Mlle de Brécourt. She had theatrical connections, and was a special favourite of Mlle Déjazet. She nursed him, cured him, and, when he was well again, introduced him to her friend. Déjazet had just established the theatre named after her, and every show after La Taverne was put on at this theatre. Fortune began to smile on the author.[3]

It is true that Candide, the first play he wrote for Mlle Déjazet, was stopped by the censor, but Les Premières Armes de Figaro, Monsieur Garat, and Les Prés Saint Gervais, produced almost in succession, had a splendid run. Garat and Gervais were done at Theatre des Varlétés and in English at Criterion Theatre in London. Les Pattes de mouche (1860, afterwards anglicized as A Scrap of Paper) obtained a similar success at the Gymnase.[3]

Fédora (1882), a work that popularized the fedora hat as well,[4] was written expressly for Sarah Bernhardt, as were many of his later plays. This was later adapted by Umberto Giordano, and he made an opera entitled Fedora. The play dealt with nihilism, which was coined from Fathers and Sons by Ivan Turgenev. He struck a new vein by introducing a strong historic element in some of his dramatic romances. Thus he borrowed Théodora (1884) from Byzantine annals (which was also adapted into an opera by Xavier Leroux), La Haine (1874) from Italian chronicles, La Duchesse d'Athénes from the forgotten records of medieval Greece. Patrie! (1869) is founded on the rising of the Dutch Geuzen at the end of the 16th century, and was made into a popular opera by Emile Paladilhe in 1886. The scene of La Sorcière (1904) was laid in Spain in the 16th century. The French Revolution furnished him three plays, Les Merveilleuses, Thermidor (1891) and Robespierre (1899). His play Gismonda (1894) was adapted into an opera by Henry Février. The last named was written expressly for Sir Henry Irving, and produced at the Lyceum theatre in London, as was Dante (1903). The Napoleonic era was revived in La Tosca (1887).[3]

Madame Sans-Gêne (1893) was written specifically for Gabrielle Réjane as the unreserved, good-hearted wife of Marshal Lefevre. It was translated into English and starred Irving and Ellen Terry at the Lyceum Theatre. Later plays were La Pisie (1905) and Le Drame des poisons (1907). In many of these plays, however, it was too obvious that a thin varnish of historic learning, acquired for the purpose, had been artificially laid on to cover modern thoughts and feelings. But a few — Patrie! and La Haine (1874), for instance — exhibit a true insight into the strong passions of past ages.[3] L'Affaire des Poisons (1907) was running at the Théâtre de la Porte Saint-Martin and was very successful at the time of his death. The play involved the poisoning camarilla under Louis XIV of France.[5] Toward the end of his life, Sardou made several recordings of himself reading passages from his works, including a scene from Patrie!.[6]

Personal life and death

Sardou married his benefactress, Mlle de Brécourt, but eight years later he became a widower, and soon after the Revolution of 1870 was married a second time, to Mlle Soulié on 17 June 1872, the daughter of the erudite Eudore Soulié, who for many years superintended the Musée de Versailles. He was elected to the Académie française in the room of the poet Joseph Autran (1813–1877), and took his seat on 22 May 1878.[3] He lived at Château de Marly for some time.

He obtained the Légion d'honneur in 1863 and was elected a member of the Académie française in 1877.[5] Sardou died on 8 November 1908 in Paris. He had been ill for a long time. Official cause of death was pulmonary congestion.[5]

Writing style

Sardou modeled his work after Eugène Scribe. It was reported in Stephen Sadler Stanton's intro to Camille and Other Plays that Sardou would read the first act of one of Scribe's plays, rewrite the rest, and then compare the two. One of his first goals when writing was to devise a central conflict followed by a powerful climax. From there, he would work backwards to establish the action leading up to it. He believed conflict was the key to drama.[7]

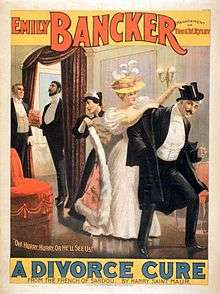

He was ranked with the two undisputed leaders of dramatic art at that time, Augier and Dumas. He lacked the powerful humour, the eloquence and moral vigour of the former, the passionate conviction and pungent wit of the latter, but he was a master of clever and easy flowing dialogue. He adhered to Scribe's constructive methods, which combined the three old kinds of comedy —the comedy of character, of manners and of intrigue— with the drame bourgeois, and blended the heterogeneous elements into a compact body and living unity. He was no less dexterous in handling his materials than his master had been before him, and at the same time opened a wider field to social satire. He ridiculed the vulgar and selfish middle-class person in Nos Intimes (1861: anglicized as Peril), the gay old bachelors in Les Vieux Garçons (1865), the modern Tartufes in Seraphine (1868), the rural element in Nos Bons Villageois (1866), old-fashioned customs and antiquated political beliefs in Les Ganaches (1862), the revolutionary spirit and those who thrive on it in Rabagas (1872) and Le Roi Carotte (1872), the then threatened divorce laws in Divorçons (1880).[3]

Legacy

Irish playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw said of La Tosca: "Such an empty-headed ghost of a shocker... Oh, if it had but been an opera!".[7] He also came up with the dismissive term "Sardoodledom" in a review of Sardou plays (The Saturday Review, 1 June 1895). Shaw believed that Sardou's contrived dramatic machinery was creaky and that his plays were empty of ideas. Sardou's advice to young playwrights on how to be successful was to "Torture the women!" as part of any play construction.

After producer Sir Squire Bancroft saw the dress rehearsal for Fedora, he said in his memoirs "In five minutes the audience was under a spell which did not once abate throughout the whole four acts. Never was treatment of a strange and dangerous subject more masterly, never was acting more superb than Sarah showed that day." [7] William Winter said of Fedora that "the distinguishing characteristic of this drama is carnality."

Sardou is mentioned in chapter two of Proust's The Guermantes Way, the third volume of In Search of Lost Time.

In New Orleans, during the period when much of its upper class still spoke French, Antoine Alciatore, founder of the famous old restaurant Antoine's, invented a dish called Eggs Sardou in honor of the playwright's visit to the city.

The Rue Victorien Sardou and Square Victorien Sardou near the Parc Sainte-Périne in Paris are named after him. There are also streets named rue Victorien Sardou in Lyon and Saint-Omer.

Works

Stage works

- La Taverne des étudiants (1854)

- Les Premières Armes de Figaro (1859), with Emile Vanderbuch

- Les Gens nerveux (1859), with Théodore Barrière

- Les Pattes de mouche (A Scrap of Paper; 1860)

- Monsieur Garat (1860)

- Les Femmes fortes (1860)

- L'écureuil (1861)

- L'Homme aux pigeons (1861), as Jules Pélissié

- Onze Jours de siège (1861)

- Piccolino (1861), comedy in 3 acts with songs[8]

- Nos Intimes! (1861)

- Chez Bonvalet (1861), as Jules Pélissié with Henri Lefebvre

- La Papillonne (1862)

- La Perle Noire (The Black Pearl; 1862)

- Les Prés Saint-Gervais (1862), with Philippe Gille and music by Charles Lecocq

- Les Ganaches (1862)

- Bataille d'amour (1863), with Karl Daclin and music by Auguste Vaucorbeil

- Les Diables noirs (1863)

- Le Dégel (1864)

- Don Quichotte (1864), rearranged by Sardou and Charles-Louis-Etienne Nuitter and music by Maurice Renaud

- Les Pommes du voisin (1864)

- Le Capitaine Henriot (1864), by Sardou and Gustave Vaez, music by François-Auguste Gevaert

- Les Vieux Garçons (1865)

- Les Ondines au Champagne (1865), as Jules Pélissié with Henri Lefebvre, music by Charles Lecocq

- La Famille Benoîton (1865)

- Les Cinq Francs d'un bourgeois de Paris (1866), with Dunan Mousseux and Jules Pélissié

- Nos Bons Villageois (1866)

- Maison neuve (1866)

- Séraphine (1868)

- Patrie! (Fatherland) (1869), adapted by Sardou in 1886 into a grand opera with music by Emile Paladilhe

- Fernande (1870)

- Le roi Carotte (1872), music by Jacques Offenbach

- Les Vieilles Filles (1872), with Charles de Courcy

- Andréa (1873)

- L’Oncle Sam (Uncle Sam; 1873)

- Les Merveilleuses (1873), music by Félix Hugo

- Le Magot (1874)

- La Haine (Hatred; 1874), music by Jacques Offenbach

- Ferréol (1875)

- Piccolino (1876), 3-act opéra-comique, with Charles-Louis-Etienne Nuitter and with music by Ernest Guiraud[9]

- L'Hôtel Godelot (1876), with Henri Crisafulli

- Dora (1877)

- Les Exilés (1877), with Gregorij Lubomirski and Eugène Nus

- Les Bourgeois de Pont-Arcy (1878)

- Les Noces de Fernande (1878), with Émile de Najac and music by Louis-Pierre Deffès

- Daniel Rochat (1880)

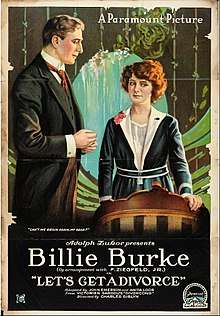

- Divorçons! (Let’s Get a Divorce; 1880), with Émile de Najac

- Odette (1881)

- Fédora (1882)

- Théodora (1884), later revised in 1907 with Paul Ferrier and music by Xavier Leroux

- Georgette (1885)

- Le Crocodile (1886), with music by Jules Massenet

- La Tosca (1887), with music by Louis Pister

- Marquise (1889)

- Belle-Maman (1889), with Raymond Deslandes

- Cléopâtre (1890), with Émile Moreau and music by Xavier Leroux[10]

- Thermidor (1891)

- Madame Sans-Gêne (1893), with Émile Moreau

- Gismonda (1894)

- Marcelle (1895)

- Spiritisme (1897)

- Paméla (1898)

- Robespierre (1899) with music by Georges Jacobi

- La Fille de Tabarin (1901), with Paul and music by Gabriel Pierné

- Les Barbares (1901), opera libretto with Pierre-Barthélemy Gheusi, music by Camille Saint-Saëns

- Dante (1903), with Émile Moreau

- La Sorcière (The Sorceress; 1903)

- Fiorella (1905), with Pierre-Barthélemy Gheusi and music by Amherst Webber

- L'Espionne (1906)

- La Pisie (1906)

- L'Affaire des Poisons (1908), as Jules Pélissié [11]

Books

- Rabàgas (1872)

- Daniel Rochet (1880)[11]

Adapted works

Translations of plays

- Nos Intimes! (1862), translated by Horace Wigan into Friends or Foes?

- La Papillonne (1864), translated by Augustin Daly into Taming of a Butterfly

- Le Degel (1864), translated by Vincent Amcotts into Adonis Vanquished

- Les Ganaches (1869) translated and adapted by Thomas William Robertson into Progress

- Nos Intimes! (1872), translated by George March into Our Friends

- Les Pres Saint-Gervais (1875), translated and adapted by Robert Reece

- Divorçons! (1882), translated into Cyprienne

- Robespierre, translated by Laurence Irving

Operas and musicals

- Patrie! (1886) an opera with music by Emile Paladihle and libretto by Sardou and Louis Gallet

- Fedora (1898) an opera by Umberto Giordano

- Tosca (1900) an opera by Giacomo Puccini

- Les Merveilleuses (1907), adapted by Basil Hood as the musical play The Merveilleuses

- Théodora (1907) an opera by Xavier Leroux

- Madame Sans-Gêne (1915) an opera by Umberto Giordano

- Gismonda (1919) an opera by Henry Février[11]

Film adaptations

- Cleopatra, directed by Charles L. Gaskill (1912, based on the play Cléopâtre)

- Princess Romanoff, directed by Frank Powell (1915, based on the play Fédora)

- The Song of Hate, directed by J. Gordon Edwards (1915, based on the play La Tosca)

- Marcella, directed by Baldassarre Negroni (Italy, 1915, based on the play Marcelle)

- Odette, directed by Giuseppe de Liguoro (Italy, 1916, based on the play Odette)

- The Witch, directed by Frank Powell (1916, based on the play La Sorcière)

- Diplomacy, directed by Sidney Olcott (1916, based on the play Dora)

- Váljunk el! (Austria-Hungary, 1916, based on the play Divorçons)

- The Chalice of Sorrow, directed by Rex Ingram (1916, based on the play La Tosca - uncredited)

- Ferréol, directed by Edoardo Bencivenga (Italy, 1916, based on the play Ferréol)

- Madame Guillotine, directed by Enrico Guazzoni and Mario Caserini (Italy, 1916, based on the play Madame Tallien)

- Fedora, directed by Gustavo Serena (Italy, 1916, based on the play Fédora)

- White Nights, directed by Alexander Korda (Austria-Hungary, 1916, based on the play Fédora)

- Patrie, directed by Albert Capellani (France, 1917, based on the play Patrie)

- Andreina, directed by Gustavo Serena (Italy, 1917, based on the play Andréa)

- Fernanda, directed by Gustavo Serena (Italy, 1917, based on the play Fernande)

- Cleopatra, directed by J. Gordon Edwards (1917, based on the play Cléopâtre, and other sources)

- Az anyaszív, directed by Sándor Góth (Austria-Hungary, 1917, based on the play Odette)

- Tosca, directed by Alfredo De Antoni (Italy, 1918, based on the play La Tosca)

- La Tosca, directed by Edward José (1918, based on the play La Tosca)

- Let's Get a Divorce, directed by Charles Giblyn (1918, based on the play Divorçons)

- Love's Conquest, directed by Edward José (1918, based on the play Gismonda)

- Fedora, directed by Edward José (1918, based on the play Fédora)

- The Burden of Proof, directed by John G. Adolfi and Julius Steger (1918, based on the play Dora)

- I nostri buoni villici, directed by Camillo De Riso (Italy, 1918, based on the play Nos Bons Villageois)

- Spiritismo, directed by Camillo De Riso (Italy, 1919, based on the play Spiritisme)

- Dora o Le spie, directed by Roberto Roberti (Italy, 1919, based on the play Dora)

- Three Green Eyes, directed by Dell Henderson (1919, based on the play Les Pattes de mouche)

- Giorgina, directed by Ubaldo Pittei and Giuseppe Forti (Italy, 1919, based on the play Georgette)

- Ferréol, directed by Franz Hofer (Germany, 1920, based on the play Ferréol)

- I borghesi di Pontarcy, directed by Umberto Mozzato (Italy, 1920, based on the play Les Bourgeois de Pont-Arcy)

- Napoleon and the Little Washerwoman, directed by Adolf Gärtner (Germany, 1920, based on the play Madame Sans-Gêne)

- Theodora, directed by Leopoldo Carlucci (Italy, 1921, based on the play Théodora)

- Rabagas, directed by Gaston Ravel (Italy, 1922, based on the novel Rabàgas)

- L'Espionne, directed by Henri Desfontaines (France, 1923, based on the play L'Espionne)

- Madame Sans-Gêne, directed by Léonce Perret (1925, based on the play Madame Sans-Gêne)

- Kiss Me Again, directed by Ernst Lubitsch (1925, based on the play Divorçons)

- Fedora, directed by Jean Manoussi (Germany, 1926, based on the play Fédora)

- Diplomacy, directed by Marshall Neilan (1926, based on the play Dora)

- Don't Tell the Wife, directed by Paul L. Stein (1927, based on the play Divorçons)

- Odette, directed by Luitz-Morat (Germany, 1928, based on the play Odette)

- A Night of Mystery, directed by Lothar Mendes (1928, based on the play Ferréol)

- The Woman from Moscow, directed by Ludwig Berger (1928, based on the play Fédora)

- L'Évadée, directed by Henri Ménessier (France, 1929, based on the play Le Secret de Délia)

- Fedora, directed by Louis J. Gasnier (France, 1934, based on the play Fédora)

- Odette, directed by Jacques Houssin and Giorgio Zambon (France/Italy, 1934, based on the play Odette)

- Les Pattes de mouche, directed by Jean Grémillon (France, 1936, based on the play Les Pattes de mouche)

- Marcella, directed by Guido Brignone (Italy, 1937, based on the play Marcelle)

- Tosca, directed by Carl Koch and Jean Renoir (Italy, 1941, based on the opera Tosca)

- That Uncertain Feeling, directed by Ernst Lubitsch (1941, based on the play Divorçons)

- Madame Sans-Gêne, directed by Roger Richebé (France, 1941, based on the play Madame Sans-Gêne)

- Fedora, directed by Camillo Mastrocinque (Italy, 1942, based on the opera Fedora)

- Dora, la espía, directed by Raffaello Matarazzo (Italy, 1943, based on the play Dora)

- Madame Sans-Gêne, directed by Luis César Amadori (Argentina, 1945, based on the play Madame Sans-Gêne)

- Pamela, directed by Pierre de Hérain (France, 1945, based on the play Paméla)

- La señora de Pérez se divorcia, directed by Carlos Hugo Christensen (Argentina, 1945, based on the play Divorçons)

- En tiempos de la inquisición, directed by Juan Bustillo Oro (Mexico, 1946, based on the play La Sorcière)

- Patrie, directed by Louis Daquin (France, 1946, based on the play Patrie)

- Distress, directed by Robert-Paul Dagan (France, 1946, based on the play Odette)

- El precio de una vida, directed by Adelqui Migliar (Argentina, 1947, based on the play Fédora)

- Tosca, directed by Carmine Gallone (Italy, 1956, based on the opera Tosca)

- Amor para Três, directed by Carlos Hugo Christensen (Brazil, 1960, based on the play Divorçons)

- Madame, directed by Christian-Jaque (France/Italy, 1961, based on the play Madame Sans-Gêne)

- La Tosca, directed by Luigi Magni (Italy, 1973, based on the play La Tosca)

- Tosca, directed by Benoît Jacquot (France, 2001, based on the opera Tosca)

References

- "SARDOU, Victorien". Who's Who. Vol. 59. 1907. p. 1556.

- McCormick (1998, 964).

-

- Encarta Dictionary, Microsoft Encarta Premium Suite 2004.

- "VICTORIEN SARDOU, DRAMATIST, DEAD; Dean of French Playwrights and Creator of Bernhardt's Famous Roles Leaves No Memoirs. FIRST PLAY WAS HISSED His Last, "L'Affaire des Poisons," He Saw Produced at 75 -- Still Running to Crowded Houses" (PDF). The New York Times. 9 November 1908.

- Fonotipia A Centenary Celebration 1904-2004 SYMPOSIUM 1261 [JW]: Classical CD Reviews- May 2005 MusicWeb-International

- Piccolino, comédie en trois actes, 1861 at Google Books

- Piccolino, opéra-comique en trois actes, 1876 at Internet Archive.

- "THE LATEST 'CLEOPATRA'". In: The New York Times, 24 October 1890.

- Cooper, Barbara T. (1998). French Dramatists, 1789-1914. Detroit, Michigan: Gale Research. ISBN 978-0-7876-1847-6.

Further reading

- Blanche Roosevelt (2009) Victorien Sardou BiblioLife ISBN 1-110-54130-9

- Stephen Sadler Stanton (1990) Camille and Other Plays: A Peculiar Position; The Glass of Water; La Dame aux Camelias; Olympe's Marriage; A Scrap of Paper Hill and Wang ISBN 0-8090-0706-1

- McCormick, John. 1998. "Sardou, Victorien." In The Cambridge Guide to Theatre. Ed. Martin Banham. Cambridge: Cambridge UP. 964. ISBN 0-521-43437-8.

- Lacour, L. 1880. Trois théâtres.

- Matthews, Brander. 1881. French Dramatists. New York.

- Doumic, R. 1895. Écrivains d'aujourd'hui. Paris.

- Sarcey, F. 1901. Quarante ans de théâtre. Vol. 6.

External links

| Look up sardoodledom in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Victorien Sardou. |