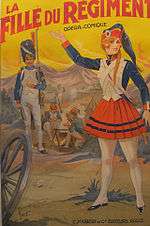

La fille du régiment

La fille du régiment (The Daughter of the Regiment) is an opéra comique in two acts by Gaetano Donizetti, set to a French libretto by Jules-Henri Vernoy de Saint-Georges and Jean-François Bayard. It was first performed on 11 February 1840 by the Paris Opéra-Comique at the Salle de la Bourse.

| La fille du régiment | |

|---|---|

| Opéra comique by Gaetano Donizetti | |

).jpg) Juliette Borghèse as Marie and François-Louis Henry as Sulpice in the premiere[2] | |

| Librettist | |

| Language | French |

| Premiere | |

The opera was written by Donizetti while he was living in Paris between 1838 and 1840 preparing a revised version of his then-unperformed Italian opera, Poliuto, as Les martyrs for the Paris Opéra. Since Martyrs was delayed, the composer had time to write the music for La fille du régiment, his first opera set to a French text, as well as to stage the French version of Lucia di Lammermoor as Lucie de Lammermoor.

La fille du régiment quickly became a popular success partly because of the famous aria "Ah! mes amis, quel jour de fête!", which requires the tenor to sing no fewer than eight high Cs – a frequently sung ninth is not written.[3] La figlia del reggimento, a slightly different Italian-language version (in translation by Calisto Bassi), was adapted to the tastes of the Italian public.

Performance history

Opéra-Comique premiere

.jpg)

The opening night was "a barely averted disaster."[4] Apparently the lead tenor was frequently off pitch.[5] The noted French tenor Gilbert Duprez, who was present, later observed in his Souvenirs d'un chanteur: "Donizetti often swore to me how his self-esteem as a composer had suffered in Paris. He was never treated there according to his merits. I myself saw the unsuccess, almost the collapse, of La fille du régiment."[6][7]

It received a highly negative review from the French critic and composer Hector Berlioz (Journal des débats, 16 February 1840), who claimed it could not be taken seriously by either the public or its composer, although Berlioz did concede that some of the music, "the little waltz that serves as the entr'acte and the trio dialogué ... lack neither vivacity nor freshness."[7] The source of Berlioz's hostility is revealed later in his review:

What, two major scores for the Opéra, Les martyrs and Le duc d'Albe, two others at the Théâtre de la Renaissance, Lucie de Lammermoor and L'ange de Nisida, two at the Opéra-Comique, La fille du régiment and another whose title is still unknown, and yet another for the Théâtre-Italien, will have been written or transcribed in one year by the same composer! M[onsieur] Donizetti seems to treat us like a conquered country; it is a veritable invasion. One can no longer speak of the opera houses of Paris, but only of the opera houses of M[onsieur] Donizetti.[7]

The critic and poet Théophile Gautier, who was not a rival composer, had a somewhat different point of view: "M[onsieur] Donizetti is capable of paying with music that is beautiful and worthy for the cordial hospitality which France offers him in all her theatres, subsidized or not."[8]

Despite its bumpy start, the opera soon became hugely popular at the Opéra-Comique. During its first 80 years, it reached its 500th performance at the theatre in 1871 and its 1,000th in 1908.[9]

Outside France

The opera was first performed in Italy at La Scala, Milan, on 3 October 1840, in Italian with recitatives by Donizetti replacing the spoken dialogue.[10] It was thought "worthless" and received only six performances. It was not until 1928 when Toti Dal Monte sang Marie that the opera began to be appreciated in Italy.[11]

La fille du régiment received its first performance in America on 7 March 1843 at the Théâtre d'Orléans in New Orleans.[12] The New Orleans company premiered the work in New York City on 19 July 1843 with Julie Calvé as Marie.[13] The Spirit of the Times (22 July) counted it a great success, and, although the score was "thin" and not up to the level of Anna Bolena or L'elisir d'amore, some of Donizetti's "gems" were to be found in it.[14] The Herald (21 July) was highly enthusiastic, especially in its praise of Calvé: "Applause is an inadequate term, ... vehement cheering rewarded this talented prima donna."[15] Subsequently the opera was performed frequently in New York, the role of Marie being a favorite with Jenny Lind, Henriette Sontag, Pauline Lucca, Anna Thillon and Adelina Patti.[16]

First given in England in Italian, it appeared on 27 May 1847 at Her Majesty's Theatre in London (with Jenny Lind and Luigi Lablache). Later—on 21 December 1847 in English—it was presented at the Surrey Theatre in London.[17]

W. S. Gilbert wrote a burlesque adaptation of the opera, La Vivandière, in 1867.

20th century and beyond

The Metropolitan Opera gave the first performances with Marcella Sembrich, and Charles Gilibert (Sulpice) during the 1902/03 season. It was then followed by performances at the Manhattan Opera House in 1909 with Luisa Tetrazzini, John McCormack, and Charles Gilibert, and again with Frieda Hempel and Antonio Scotti in the same roles at the Met on 17 December 1917.[18]

It was revived at the Royal Opera, London, in 1966 for Joan Sutherland. On 13 February 1970, in concert at Carnegie Hall, Beverly Sills sang the first performance in New York since Lily Pons performed it at the Metropolitan Opera House in 1943.[19][20]

This opera is famous for the aria "Ah! mes amis, quel jour de fête!" (sometimes referred to as "Pour mon âme"), which has been called the "Mount Everest" for tenors. It features eight high Cs (a ninth, frequently inserted, is not written). Luciano Pavarotti broke through to stardom via his 1972 performance alongside Joan Sutherland at the Met, when he "leapt over the 'Becher's Brook' of the string of high Cs with an aplomb that left everyone gasping."[21]

More recently, in a 20 February 2007 performance of the opera at La Scala, Juan Diego Flórez sang "Ah! mes amis", and then, on popular demand, repeated it,[22][23] breaking a tradition against encores at La Scala that had lasted nearly three-quarters of a century.[22] Flórez repeated this feat on 21 April 2008, the opening night of Laurent Pelly's production (which had been originally staged in 2007 at Covent Garden in London) at the Metropolitan Opera in New York, with Natalie Dessay as Marie.[24][25][26][27][28] A live performance of this Met production, without an encore of "Ah! mes amis", was cinecast via Metropolitan Opera Live in HD to movie theaters worldwide on 26 April 2008. On 3 March 2019, Mexican tenor Javier Camarena also sang an encore of the aria at the Met, singing 18 high Cs in a performance which was broadcast live worldwide via Metropolitan Opera radio and cinecast worldwide via Metropolitan Opera Live in HD.[29]

As a non-singing role, the Duchess of Crakenthorp is often played by non-operatic celebrities, including actresses such as Dawn French, Bea Arthur, Hermione Gingold, and Kathleen Turner, or by retired opera greats such as Kiri Te Kanawa and Montserrat Caballé. In 2016, US Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a lifelong opera fan, played the Duchess on opening night of the Washington National Opera's production.[30]

Today, the opera is frequently performed to the point that it has become part of the standard repertoire.[31]

Films

The opera was filmed in a silent film in 1929; a sound film with Anny Ondra in 1933 in German and separately in French; in 1953; and in 1962 with John van Kesteren as Tonio.[32]

Roles

.jpg)

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 11 February 1840 (Conductor: Gaetano Donizetti)[33] |

|---|---|---|

| Marie, a vivandière | coloratura soprano | Juliette Borghese[34] |

| Tonio, a young Tyrolean | tenor | Mécène Marié de l'Isle |

| Sergeant Sulpice | bass | François-Louis Henry ("Henri")[34] |

| The Marquise of Berkenfield | contralto | Marie-Julie Halligner ("Boulanger") |

| Hortensius, a butler | bass | Edmond-Jules Delaunay-Ricquier |

| A corporal | bass | Georges-Marie-Vincent Palianti |

| A peasant | tenor | Henry Blanchard |

| The Duchess of Crakentorp | spoken role | Marguerite Blanchard |

| A notary | spoken role | Léon |

| French soldiers, Tyrolean people, domestic servants of the Duchess | ||

Synopsis

- Time: The Napoleonic Wars, early 19th century

- Place: The Swiss Tyrol[35]

Act 1

War is raging in the Tyrols and the Marquise of Berkenfield, who is traveling in the area, is alarmed to the point of needing smelling salts to be administered by her faithful steward, Hortensius. While a chorus of villagers express their fear, the Marquise does the same: Pour une femme de mon nom / "For a lady of my family, what a time, alas, is war-time". As the French can be seen to be moving away, all express their relief. Suddenly, and provoking the fear of the remaining women who scatter, Sergeant Sulpice of the Twenty-First Regiment of the French army [in the Italian version it is the Eleventh] arrives and assures everyone that the regiment will restore order.

Marie, the vivandière (canteen girl) of the Regiment, enters, and Sulpice is happy to see her: (duet: Sulpice and Marie: Mais, qui vient? Tiens, Marie, notre fille / "But who is this? Well, well, if it isn't our daughter Marie"). Then, as he questions her about a young man she has been seen with, she identifies him as Tonio, a Tyrolean [in the Italian version: Swiss]. At that moment, Tonio is brought in as a prisoner, because he has been seen prowling around the camp. Marie saves him from the soldiers, who demand that he must die, by explaining that he had saved her life when she nearly fell while mountain-climbing. All toast Tonio, who pledges allegiance to France, and Marie is encouraged to sing the regimental song: (aria: Chacun le sait, chacun le dit / "Everyone knows it, everyone says it"). Sulpice leads the soldiers off, taking Tonio with them, but he runs back to join her. She quickly tells him that he must gain the approval of her "fathers": the soldiers of the Regiment, who found her on the battlefield as an abandoned baby, and adopted her. He proclaims his love for her (aria, then love duet with Marie: Depuis l'instant où, dans mes bras / "Ever since that moment when you fell and / I caught you, all trembling in my arms..."), and then the couple express their love for each other.

At that point, Sulpice returns, surprising the young couple, who leave. The Marquise arrives with Hortensius, initially afraid of the soldier, but is calmed by him. The Marquise explains that they are trying to return to her castle and asks for an escort. When hearing the name Berkenfield, Sulpice immediately recognizes it from a letter found with Marie as an infant. It is discovered that Marie is actually the Marquise's long-lost niece. Marie returns and is surprised to be introduced to her aunt. The Marquise commands that Marie accompany her and that she will be taught to be a proper lady. Marie bids farewell to her beloved regiment just as Tonio enters announcing that he has enlisted in their ranks: (aria: Ah! mes amis, quel jour de fête / "Ah, my friends, what an exciting day"). When he proclaims his love for Marie, the soldiers are horrified, but agree to his pleading for her hand. However, they tell him that she is about to leave with her aunt: (Marie, aria: Il faut partir / "I must leave you!"). In a choral finale in which all join, she leaves with the Marquise and Tonio is enraged.

Act 2

Marie has been living in the Marquise's castle for several months. In a conversation with Sulpice, the Marquise describes how she has sought to modify most of Marie's military manners and make her into a lady of fashion, suitable to be married to her nephew, the Duke of Crakenthorp. Although reluctant, Marie has agreed and Sulpice is asked to encourage her. Marie enters and is asked to play the piano, but appears to prefer more martial music when encouraged by Sulpice and sings the regimental song. The Marquise sits down at the piano and attempts to work through the piece with Marie who becomes more and more distracted and, along with Sulpice, takes up the regimental song.

Marie is left alone: (aria: Par le rang et par l'opulence / "They have tried in vain to dazzle me"). As she is almost reconciled to her fate, she hears martial music and is joyously happy (cabaletta: Oh! transport! oh! douce ivresse / "Oh bliss! oh ectasy!"), and the Regiment arrives. With it is Tonio, now an officer. The soldiers express their joy at seeing Marie, and Marie, Tonio and Sulpice are joyfully reunited (trio, Marie, Sulpice, Tonio: Tous les trois réunis / "We three are reunited"). Tonio mentions he has just learned a secret, via his uncle the burgermeister, that he cannot reveal.

The Marquise enters, horrified to see soldiers. Tonio asks for Marie's hand, explaining that he risked his life for her (aria, Tonio: Pour me rapprocher de Marie, je m'enrôlai, pauvre soldat / "In order to woo Marie, I enlisted in the ranks"), but she dismisses him scornfully. Tonio reveals that he knows that the Marquise never had a niece. She orders him to leave and Marie to return to her chambers; after they leave, the Marquise confesses the truth to Sulpice: Marie is her own illegitimate daughter. In the circumstances, Sulpice promises that Marie will agree to her mother's wishes.

The Duchess of Crakenthorp, her son the groom-to-be, and the wedding entourage arrive at the Marquise's castle. Marie enters with Sulpice, who has given her the news that the Marquise is her mother. Marie embraces her and decides she must obey. But at the last minute the soldiers of the Regiment storm in (chorus: soldiers, then Tonio: Au secours de notre fille / "Our daughter needs our help") and reveal that Marie was a canteen girl. The wedding guests are offended by that fact, but are then impressed when Marie sings of her debt to the soldiers (aria, Marie: Quand le destin, au milieu de la guerre / "When fate, in the confusion of war, threw me, a baby, into their arms"). The Marquise is deeply moved, admits she is Marie's mother, and gives her consent to Marie and Tonio, amid universal rejoicing (final chorus: Salut à la France! / "Hurrah for France! For happy times!").[36]

Recordings

| Year | Cast (Marie, Tonio, Sulpice, La Marquise) |

Conductor, Opera house and orchestra |

Label[37] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | Lina Pagliughi, Cesare Valletti, Sesto Bruscantini, Rina Corsi |

Mario Rossi RAI Milan orchestra and chorus |

CD: Aura Music Cat: LRC 1115 |

| 1960 | Anna Moffo, Giuseppe Campora, Giulio Fioravanti, Iolande Gardino |

Franco Mannino RAI Milan orchestra and chorus |

CD: GALA Cat: 100713 |

| 1967 | Joan Sutherland, Luciano Pavarotti, Spiro Malas, Monica Sinclair |

Richard Bonynge Royal Opera House orchestra and chorus |

CD: Decca Originals Cat: 478 1366 |

| 1970 | Beverly Sills, Grayson Hirst, Fernando Corena, Muriel Costa-Greenspon |

Roland Gagnon American Opera Society Carnegie Hall |

CD: Opera d'Oro Cat: B000055X2G |

| 1986 | June Anderson, Alfredo Kraus, Michel Trempont, Hélia T'Hézan |

Bruno Campanella Opéra National de Paris orchestra and chorus |

VHS Video: Bel Canto Society Cat: 628 |

| 1995 | Edita Gruberová, Deon van der Walt, Philippe Fourcade, Rosa Laghezza |

Marcello Panni Munich Radio Orchestra Chor des Bayerischer Rundfunk |

CD: Nightingale Cat: NC 070566-2 |

| 2007 | Natalie Dessay, Juan Diego Flórez, Alessandro Corbelli, Felicity Palmer, Duchess: Dawn French |

Bruno Campanella Royal Opera House orchestra and chorus (Live recording on 27 January)[38] |

DVD: Virgin Classics Cat: 5099951900298 |

| 2007 | Natalie Dessay, Juan Diego Flórez, Carlos Álvarez, Janina Baechle, Duchess: Montserrat Caballé |

Yves Abel Vienna State Opera orchestra and chorus |

CD: Unitel Cat: A04001502[39] |

References

Notes

- See the "Notice bibliographique" at the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- See the "Notice bibliographique" at the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

- "Tenor on top of the high C’s in Donizetti opera" by Mike Silverman, AP News, 5 February 2019

- Ashbrook 1982, p. 146.

- Ashbrook 1982, p. 651, note 45.

- Gilbert Duprez, Souvenirs d'un chanteur, 1880, p. 95 (at the Internet Archive).

- Quoted and translated by Ashbrook 1982, p. 146.

- Ashbrook 1982, p. 651, note 46.

- Wolff, S. Un demi-siècle d'opéra-comique (1900–1950). Paris: André Bonne, 1953, pp. 76–77

- Ashbrook 1982, p. 568; Warrack & West 1992, p. 243 (recitatives by Donizetti); Loewenberg 1978, column 804, has 30 October 1840 for Milan.

- Ashbrook 1982, p. 651, note 50.

- Loewenberg 1978, column 805; Warrack & West 1992, p. 243.

- Loewenberg 1978, column 805.

- Lawrence, 1988, p. 215.

- Quoted in Lawrence, 1988, p. 215.

- Kobbé 1919, p. 355; Lawrence 1995, p. 226 (Anna Thillon).

- Loewenberg 1978, column 805 (both London performances); Warrack & West 1992, p. 243 (Her Majesty's in London with Lind and Lablache).

- Kobbé 1919, p. 355.

- "Beverly Sills – beverlysillsonline.com – Biography, Discography, Annals, Pictures, Articles, News". www.beverlysillsonline.com.

- Metropolitan Opera archives database

- James Naughtie, "Goodbye Pavarotti: Forget the Pavarotti with Hankies. He was Better Younger", The Times (London), 7 September 2007. Retrieved 22 April 2008

- "Peruvian tenor breaks La Scala encore taboo". CBC News. 23 February 2007. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "Show-Stopping Aria Encored at the Met". NPR. 23 April 2008. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "Peruvian tenor Juan Diego Florez wows crowd at Met with 18 high Cs". New York Daily News. Associated Press. 22 April 2008. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- Bernheimer, Martin (23 April 2008). "La fille du régiment, Metropolitan Opera, New York". Financial Times. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- Waleson, Heidi (1 May 2008). "The Place to Be if You Like Hearing High C's". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- Kirshnit, Fred (23 April 2008). "The Met's New La Fille du Régiment". New York Sun. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- Hoelterhoff, Manuela (22 April 200). "Lederhosen and Laughs as Met Tenor Struts His High C". Bloomberg.com. Archived version retrieved 7 June 2019.

- Salazar, Francisco (3 March 2019). "Javier Camarena Makes Met Opera HD History". OperaWire. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- "Standing ovation greets Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg cameo in DC opera". The Guardian. 14 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- Report of performances from 1 January 2012 forward on operabase.com Retrieved 9 May 2014

- Die Regimentstochter (1962) on IMDb

- Casaglia, Gherardo (2005)."Premiere details". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- See the "Notice de spectacle" at the BnF.

- Osborne, p. 273

- Synopsis Archived 3 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine in part from the Metropolitan Opera as well as the booklet accompanying the 1967 Decca recording.

- Source for recording information: Recording(s) of La fille du régiment on operadis-opera-discography.org.uk

- Donizetti: La Fille Du Régiment / Dessay, Flórez

- DONIZETTI, G.: La fille du regiment (Vienna State Opera, 2007)

Cited sources

- Ashbrook, William (1982). Donizetti and His Operas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23526-X

- Kobbé, Gustav (1919). The Complete Opera Book, first English edition. London & New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. View at the Internet Archive.

- Lawrence, Vera Brodsky (1988). Strong on Music: The New York Music Scene in the Days of George Templeton Strong, 1836–1875. Volume I: Resonances 1836–1850. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504199-6

- Loewenberg, Alfred (1978). Annals of Opera 1597–1940 (third edition, revised). Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-87471-851-5.

- Osborne, Charles (1994). The Bel Canto Operas of Rossini, Donizetti, and Bellini. Portland, OR: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-71-3

- Warrack, John; West, Ewan (1992). The Oxford Dictionary of Opera. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-869164-5.

Other sources

- Allitt, John Stewart (1991). Donizetti: in the light of Romanticism and the teaching of Johann Simon Mayr, Shaftesbury: Element Books, Ltd; Rockport, MA: Element, Inc.

- Ashbrook, William; Hibberd, Sarah (2001). "Gaetano Donizetti", pp. 224–247 in The New Penguin Opera Guide, edited by Amanda Holden. New York: Penguin Putnam. ISBN 0-14-029312-4.

- Black, John (1982). Donizetti's Operas in Naples, 1822–1848. London: The Donizetti Society. OCLC 871846923

- Lawrence, Vera Brodsky (1995). Strong on Music: The New York Music Scene in the Days of George Templeton Strong. Volume II. Reverberations, 1850–1856. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-47011-5.

- Melitz, Leo (2015) [1921]. The Opera Goer's Complete Guide. ISBN 978-1330999813 OCLC 982924886. (Source of synopsis)

- Sadie, Stanley, (Ed.); John Tyrell (Exec. Ed.) (2004). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. 2nd edition. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-19-517067-2 (hardcover). ISBN 0-19-517067-9 OCLC 419285866 (eBook).

- Weinstock, Herbert (1963). Donizetti and the World of Opera in Italy, Paris, and Vienna in the First Half of the Nineteenth Century, New York: Pantheon Books. LCCN 63-13703.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to La fille du régiment. |

- Donizetti Society (London) website

- La fille du régiment: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Libretto (with some portions of the score) from archive.org (in Italian and English)