Ichthyopterygia

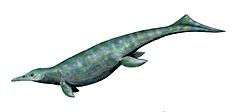

Ichthyopterygia ("fish flippers") was a designation introduced by Sir Richard Owen in 1840 to designate the Jurassic ichthyosaurs that were known at the time, but the term is now used more often for both true Ichthyosauria and their more primitive early and middle Triassic ancestors.[1][2]

| Ichthyopterygians | |

|---|---|

| |

| Utatsusaurus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | †Ichthyosauriformes |

| Superorder: | †Ichthyopterygia Owen, 1840 |

| Subgroups | |

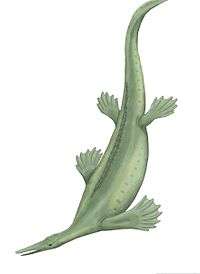

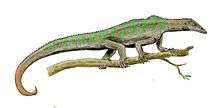

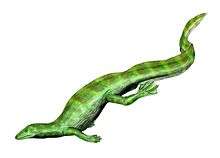

Basal ichthyopterygians (prior to and ancestral to true Ichthyosauria) were mostly small (a meter or less in length) with elongated bodies and long, spool-shaped vertebrae, indicating that they swam in a sinuous, eel-like manner. This allowed for quick movements and maneuverability that were advantages in shallow-water hunting.[3] Even at this early stage, they were already very specialised animals with proper flippers, and would have been incapable of movement on land.

These animals seem to have been widely distributed around the coast of the northern half of Pangea, as they are known the Late Olenekian and Early Anisian (early part of the Triassic period) of Japan, China, Canada, and Spitsbergen (Norway). By the later part of the Middle Triassic, they were extinct, having been replaced by their descendants, the true ichthyosaurs.

Taxonomy

- Superorder Ichthyopterygia

- ? Genus Isfjordosaurus

- ? Family Omphalosauridae

- Family Parvinatatoridae

- Family Thaisauridae

- Family Utatsusauridae

- Eoichthyosauria

- Order Grippidia

- Order Ichthyosauria

Phylogeny

Below is a cladogram modified from Cuthbertson et al., 2013.[4]

| Ichthyopterygia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Motani, R. (1997). "Temporal and spatial distribution of tooth implantation in ichthyosaurs". In J. M. Callaway; E. L. Nicholls (eds.). Ancient Marine Reptiles. Academic Press. pp. 81–103.

- Motani, R.; Minoura, N.; Ando, T. (1998). "Ichthyosaurian relationships illuminated by new primitive skeletons from Japan". Nature. 393 (6682): 255–257. doi:10.1038/30473.

- Motani, R. (2000). "Rulers of the Jurassic Seas". Scientific American. 283 (6): 52–9. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1200-52. PMID 11103459.

- Cuthbertson, R. S.; Russell, A. P.; Anderson, J. S. (2013). "Cranial morphology and relationships of a new grippidian (Ichthyopterygia) from the Vega-Phroso Siltstone Member (Lower Triassic) of British Columbia, Canada". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (4): 831. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.755989.

General references

- Ellis, Richard, (2003) Sea Dragons - Predators of the Prehistoric Oceans. University Press of Kansas

- McGowan, C & Motani, R. (2003) Ichthyopterygia, Handbook of Paleoherpetology, Part 8, Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Ichthyopterygia |