Grippia

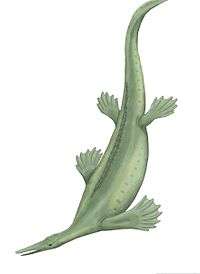

Grippia is a genus of ichthyosaur, an extinct group of reptiles that resembled dolphins. These ichthyosaurs were small, at 1–1.5 m (3.3–4.9 ft) in length. Fossil remains from Svalbard from the specimen SVT 203 were originally assigned to Grippia longirostris but are now thought to have belonged to a non-ichthyopterygian diapsid related to Helveticosaurus.[1][2]

| Grippia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Superorder: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | †Grippia Wiman, 1929 |

| species | |

| |

Discovery History

Fossils have been found along the coasts of Greenland, China, Japan, Norway, and Canada (Sulfur Mountain Formation); of Early Triassic age. No complete skeletons has ever been found. However, well-preserved remains have been found, with the most notable ones including:

- The Marine Ironstone found in Agardh Bay Norway. This specimen consists of a partial skull fossil; however, it was lost during World War II and presumably destroyed.[3]

- Previously, the Vega Phroso Siltstone Member of the Sulphur Mountain Formation in British Columbia. This specimen consists of a well preserved forelimb, several ribs, and a single centrum.[4] However, it has now been reclassified as Gulosaurus helmi, a close relative of Grippia.[5]

Taxonomy

Currently there is only one species belonging to the genus Grippia, this species is Grippia longirostris.

Grippia longirostris was an entirely marine species and is considered to be the most basal example of Ichthyopterygia. G.longirostris measured in at 1-1.5m (3.3-4.9 feet) in length making it the smallest species within the superorder Ichthyopterygia. Other definitive features of G.longirostris include the arrangement of carpals and metacarpals that constitute the forelimbs and the morphology of the skull. Members of this species swam via lateral movements of their tail similar to that of a modern-day eel.

Evolution

Ichthyopterygia are fully aquatic reptiles that evolved from terrestrial tetrapods, with no transitional lineage being discovered so far. Grippia is one of earliest examples of the superorder Ichthyopterygia and is fully adapted to aquatic life.[6]

Grippia are believed to have lived from 250-235 Ma during the Olenekian – Anisian of the early to mid-Triassic. Grippia are considered to be basal ichthyosaurs along with several other early genus, with Grippia being the most basal of all of them. This is due to its primitive anatomy when compared to older ichthyosaurs and because Grippia is the most thoroughly studied out of all basal ichthyosaurs.[2]

It is hypothesised that Grippia became extinct because it was outcompeted by more advanced ichthyosaurs. This limited the amount of food that Grippia could secure, eventually leading it to its extinction around 235 Ma.[7]

Below is a cladogram which represents Ichthyopterygia showing how Grippia diverged early in the lineage.[7]

| Ichthyopterygia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Biology

The skeletal structure of G. longirostris has been documented, especially the forelimbs by Ryosuke Motani in 1998 and the skull by Ryosuke Motani in 2000 . These studies involved modern documentation and research of previously discovered specimens.

Skull

Several different Grippia skulls have been analyzed since 1929. Seven well known cranial specimens belonging to G. longirostris were reanalyzed, in order to construct detailed descriptions of each specimen and to form a coherent compilation to represent the genus as a whole. An important thing to note is how no skull has been found to have a snout; therefore any descriptions of the snout are speculative.[2]

Montani constructed several diagrams based on his analysis, which depict the skull of G. Lonirostris as:

- Having a narrow shape.

- Possessing orbits that are larger than the upper temporal fenestra.

- The quadratojugal does not enter the upper temporal fenestra.

- The anterior margin of the external naris is formed by the premaxilla.

- The postfrontal have a posterior process that overlaps the bone of the large postorbital, similar to the skulls of other basal ichthyosaurs.[2]

Forelimbs

The forelimbs of G.longirostris are characteristic of the species. Descriptions created by Wiman in 1933 originally depicted G.longirostris as having very primitive forelimbs that were not yet completely specialized for aquatic life.[8] These descriptions involved the presence of “hoofs” at the tips of each digit, this observation has since been discredited.[9]

The most recent descriptions of the forelimbs were performed in 1998 by Motani. This analysis focused on one specimen that was nearly complete, although it was determined to be missing several distal segments of the phalanges.[9] This study revealed:

- Grippia possesses pentadactyl limbs.

- The humerus and phalanges are well developed.

- It possessed an articular radius.

- The ulna and radius extend in a wide fan shape.

- The first four proximal and distal carpals aid in separating the metacarpals.

- The second to fourth metacarpals and phalanges are similar to that of other amniotes, however they are flattened.

- The first and fifth metacarpals and phalanges are lunate in appearance and concave inwards towards the interior carpals.

- The phalanges of the distal end of the fourth and fifth digits appear to take more of an oval shape.[9]

Lifestyle

G. longirostris were well adapted to an aquatic lifestyle during early – mid Triassic.[9] They inhabited equatorial to equatorial shallow coastal seas. This paleohabitat was based upon how areas where fossils are found were at equatorial latitudes during the early Triassic when these animals lived.

The exact diet of these animals is highly debated. Analysis of dental remains belonging to G. Longirostris has shown blunt posterior teeth and replacement maxillary teeth, which suggests that these animals practiced an omnivorous feeding style.[6] This evidence is contradictory when cross examined against previous work done in the thirties and eighties, which theorized that G. Longirostris practiced a diet specialized in mollusca and small fish.[1] All of these results were based on samples that did not include an existing snout, therefore they were highly speculative and paleontologists will not know what these animals ate until a full skull is found.

Trivia

- The first G. longirostris skull was found in 1929. Many palaeontologists believe it was the most complete specimen ever found, however, it was destroyed in a bombing raid on Germany in WWII.

- Grippia is Greek for anchor.

See also

- List of ichthyosaurs

- Timeline of ichthyosaur research

References

- Mazin, J.-M. (1981). "Grippia longirostris Wiman, 1929, un Ichthyopterygia primitif du Trias inférieur du Spitsberg". Bulletin du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle. 4: 317–340.

- Motani, R (2000). "Skull of Grippia longirostris: no contradiction with a diapsid affinity for the Ichthyopterygia". Palaeontology. 43: 1–14. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00115.

- Wilman, C. (1929). "Eine neue Reptilian-Ordnung aus der Trias Spitzbergens". Bulletin of Geological Institutions of the University of Upsala. 22: 183–196.

- Cuthbertson, R.S.; Russel, A.P.; Anderson, J.S. (2013). "Cranial morphology and relationships of a new grippidian (Ichtyopterygia) from the Vega-Phroso Siltstone Member (Lower Triassic) of British Columbia, Canada". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (4): 831–847. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.755989.

- Cuthbertson, Robin S.; Russell, Anthony P.; Anderson, Jason S. (2013). "Cranial morphology and relationships of a new grippidian (Ichthyopterygia) from the Vega-Phroso Siltstone Member (Lower Triassic) of British Columbia, Canada". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 33 (4): 831–847. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.755989.

- Motani, R. (1997). "Redescription of the dentition of grippia longirostris (ichthyosauria) with a comparison with utatsusaurus hataii". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17: 39–44. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10010951.

- Motani, R.; Manabe, M.; Dong, Z.M. (1999). "The Status of Humalayasaurus Tibetensis (Ichthyopterygia)". Paludicola. 2: 174–181.

- Brinkman, Z.X.; Nicholls, E.L. (1992). "A Primitive Ichthyosaur from the Lower Triassic of British Columbia, Canada". Palaeontology. 35: 465–474.

- Motani, R. (1998). "First Complete Forefin of the Ichthyosaur Grippia Longirostris from the Triassic of Spitsbergen". Palaeontology. 41: 591–599.