Ambler, Pennsylvania

Ambler is a borough in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, in the United States. It is located approximately 16 miles (26 km) north of the city center of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Borough of Ambler | |

|---|---|

Lindenwold Castle | |

Seal | |

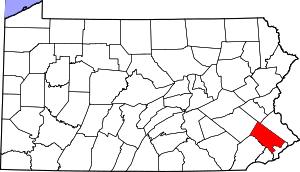

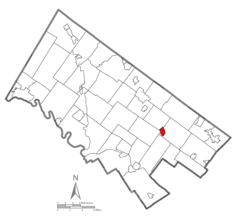

Location of Ambler in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. | |

Ambler Location of Ambler in Pennsylvania  Ambler Ambler (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 40°09′18″N 75°13′13″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| County | Montgomery |

| Settled | 1682[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-manager |

| • Mayor | Jeanne Sorg |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.85 sq mi (2.21 km2) |

| • Land | 0.85 sq mi (2.21 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 220 ft (70 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 6,417 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 6,491 |

| • Density | 7,618.54/sq mi (2,940.73/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 19002 |

| Area code(s) | 215, 267, and 445 |

| FIPS code | 42-02264 |

| Website | http://www.boroughofambler.com |

History

Lenni Lenape

The historical territory of the Lenni Lenape was in the Delaware River Valley, in an area reaching from Cape Henlopen, Delaware, northward towards the lower Hudson Valley in southern New York. The area towards the south, including what is now Philadelphia and nearby Ambler, was the home of a linguistic group called the Unami.[4] According to tradition, the Lenape established a peace treaty in with Quaker William Penn in the 1680s.[5]

Harmer family

William and George Harmer are listed among the Quakers who emigrated to Pennsylvania in 1682.[6] In 1716, William and George Harmer purchased a 408-acre tract from William Penn, an area including most of what now is Ambler Borough.[7] They are credited as the first landholders to actually settle in the area.[8] William Harmer built a grist mill powered by the Wissahickon Creek, "the first commercial venture in the Ambler area".[9] He also built a stone dwelling with casement windows and diamond shaped leaded glass, near what is now the intersection of Butler Pike and Morris Road. After his death in 1731, the house, mill, and property were sold to Morris Morris and his wife Susanna Heath Morris.[9]

Village of Wissahickon

Residents sought permission from the Crown to build roads in the area. The first road built in Ambler, now known as Mt. Pleasant Avenue, was confirmed in 1730. It went from Harmer's Mill to the North Wales Road (now Bethlehem Pike).[7] Butler Pike was created in 1739, and went through the town, which was known at that time as the Village of Wissahickon, after the Wissahickon Creek.[10]:7

The area at the crossroads of Butler and Bethlehem Pike was roughly the village center. It was first known as Gilkey's Corner, named for an inn which was built around 1778 and managed by Andrew Gilkinson (or Gilkeson). After 1878, the area was known as "Rose Valley".[11]:32

As of 1790, Jonathan Thomas purchased half an acre of land from Gilkinson and sited a tannery at the intersection,[11] causing a nearby creek to be nicknamed "Tannery Run".[7] As of 1810, the tannery was sold by his son, David Thomas, to Joseph Rutter.[11] As the "Rose Valley Tannery", it is mentioned as being one of the oldest in the county.[12] It later became the property of Alvin Faust and the firm A. D. Faust Sons.[11][12]

Increasingly from 1750 to 1850, industries developed throughout the watershed, using local waterways to provide power and carry away waste. The area supported nine mills, producing flour, timber, paper and cloth.[10]:7 They are identified by Dr. Mary Hough as Plumly Mill (first owned by William Harmer), Fulling Mill (owned by Andrew and Mary Ambler), Thomson's Mill, Reiff Mill, Wertsner Mill, Hague Mill, Burk Mill, a Silk Mill, and a Clover and Chopping and Saw Mill.[11]:9–32 However, as steam power replaced water power in the 1870s and 1880s, the mills were unable to compete, and were abandoned.[11]:27

Mary Johnson Ambler

In 1855, Wissahickon Station became a stop on the North Pennsylvania Railroad line.[10]:7 On July 17, 1856, the town was the site of a disastrous train accident: The Great Train Wreck of 1856. The northbound Shackamaxon, a picnic excursion train, and the southbound Aramingo collided head on, killing 59 people instantly, with another 86 injured. Mary Johnson Ambler, a local Quaker woman, walked two miles to the crash site, bringing medical supplies and directing rescue efforts.[13][14] She turned her house at Tennis Avenue and Main Street into an impromptu hospital for nursing the survivors.[13][15] Thirteen years later, in 1869, the railway company renamed the station Ambler in her honor. The post office followed suit, and when the borough was formally incorporated on June 16, 1888,[16] it too took the name of Ambler, in honor of Mary Johnson Ambler.[10]:7

Keasbey and Mattison

In 1881, the Keasbey and Mattison Company, whose business included the manufacture of asbestos, moved to Ambler from Philadelphia. Ambler's location along the railroad line was a primary consideration in the location of Keasbey and Mattison Company in Ambler, as it meant that raw asbestos could be easily brought in from Quebec and finished products sent out to markets. Another consideration was the availability of magnesium carbonate, from local dolomite mines.[17] The original K&M factory was built as of 1883.[18]

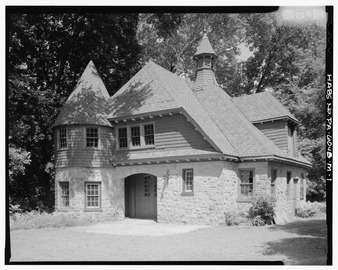

When the company arrived, the town consisted of "70 houses, 250 residents, a drug store, general store and a few other businesses."[19] Keasbey and Mattison invested heavily in the town, bringing in Southern Italian stoneworkers to build 400 houses for workers and managers, as well as offices, an opera house, the Trinity Memorial Episcopal Church,[20][21] and Mattison's personal estate, Lindenwold Castle.[22][23] Many of the Italians stayed in Ambler, helping to form its cultural identity. Maida, Calabria is the town's sister city today.[24] The company also employed African Americans, originally from West Virginia, in the less-desirable wet-processing areas of the asbestos plant. They tended to settle in west and south Ambler.[7][17]

By World War I, Ambler was known as the "asbestos capital of the world".[25] However, the Great Depression took its toll, and the company was sold to an English concern, Turner & Newall (T&N), in 1934.[22] The plant continued to operate under the K&M name.

In England in 1924, doctors reported the first case of asbestosis, a chronic illness caused by the inhalation of asbestos fibers.[26] By the 1950s, evidence linking asbestos to cancer was mounting. Richard Doll, an epidemiologist at Turner and Newall, reported (in spite of company pressure) that people exposed to asbestos for 20 or more years had a 10 times higher risk of developing lung cancer than the general population. Also, a formerly rare and almost always fatal cancer, mesothelioma, was reported in epidemic proportions near asbestos mines in South Africa. In the 1960s, the British Journal of Industrial Medicine indicated that simply living near an asbestos factory, or in an asbestos-insulated building, increased mesothelioma risk.[22]

Turner & Newall operated the factory until it closed in 1962, then sold the property to CertainTeed Corporation and Nicolet Industries.[27] By 1973, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), began to restrict the use of asbestos, stopping the sale of insulation spray in 1973, and of solid asbestos insulation in 1975.[22] In 1974, Nicolet held a competition, offering a $20,000 prize for the proposal of a "feasible commercial application" for its waste chalk piles.[28] Nicolet filed for bankruptcy in 1987.[25] By 1989, most remaining products were banned, under the 1989 Asbestos Ban and Phaseout Rule. Although the Ban was struck down in 1991, few asbestos-based products remain in the domestic marketplace.[22]

Federal-Mogul, an American automotive supplier, purchased the remaining assets of Turner & Newall in 1998.[29] As health concerns about asbestos became widely known, it too found itself in Chapter 11 bankruptcy due to asbestos liability.[30]

Legacy of asbestos

A 2011 study by the Pennsylvania Department of Health reviewed data from 1992 to 2008, and reported that mesothelioma was diagnosed 3.1 times more often in Ambler residents than in other Pennsylvania residents. The higher rates were attributed to previous asbestos exposure in the factories.[22]

In Ambler, where more than 1.5 million cubic yards of asbestos waste were discarded in a 25-acre area known as the "White Mountains",[22] contamination remains an issue.[31] From 1973 to 1993 the United States EPA oversaw remediation of the White Mountains, renamed the "Ambler Asbestos Piles".[22] It was proposed to the National Priorities List (NPL) as a Superfund site on October 10, 1984, and formally added to the list as of June 10, 1986. Various remedies were completed as of August 30, 1993 and the site was consequently deleted from the National Priorities List on December 27, 1996, after remediation.[32] The site is reviewed every five years by the EPA.[22]

Local government has made redevelopment of the sites a priority. A 2005 proposal for a 17-story condominium tower was withdrawn after community opposition to the project. One of the concerns was asbestos waste at the location. In 2009 the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) designated the proposed development as part of a second Superfund site, the BoRit Asbestos Site.[22] The site includes an asbestos waste pile, an 11-acre pond and a former park.[33] The EPA estimated that it would complete the initial cleanup phase at the BoRit site as of 2015.[22]

In 2013, Heckendorn Shiles Architects and Summit Realty Advisers successfully converted the derelict factory and smokestack of the Keasbey & Mattison company into a LEED Platinum Certified multi-tenant office building, the Ambler Boiler House. The adaptive reuse project won support from the EPA’s Brownfields Program and the EnergyWorks program. The renovations cost $16 million, and have resulted in a building with substantial green features including a grey-water system, geothermal energy, solar panels and a reflective roof system, and high-efficiency glass.[22][34]

Historic buildings

Dawesfield was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1991.[35] During the American Revolutionary War, "Dawesfield" was the property of James Morris, and was used by General George Washington as a headquarters from October 21 to November 20, 1777.[36] James Morris also owned one of the mills in the Ambler area.

Dawesfield House, 1908

Dawesfield House, 1908 Mill belonging to James Morris, Montgomery County, PA, US, 1908

Mill belonging to James Morris, Montgomery County, PA, US, 1908 Remains of Paper Mill, Wissahickon Creek, 1908

Remains of Paper Mill, Wissahickon Creek, 1908 Mary Ambler homestead, c. 1936

Mary Ambler homestead, c. 1936

The Keasbey-Mattison houses are of interest in part because of the class differences revealed in the construction of different types of houses for workers, supervisors, and administrators,[37] (not to mention Lindenwold Castle, home of Mattison himself.)[38]

Workman's row houses

Workman's row houses Workman's two-story houses

Workman's two-story houses Supervisor's house

Supervisor's house Supervisor's house

Supervisor's house Victorian Executive's carriage house/barn

Victorian Executive's carriage house/barn Victorian Executive's house

Victorian Executive's house

Other buildings of interest, some of which no longer exist, include:

Opera House, 1906

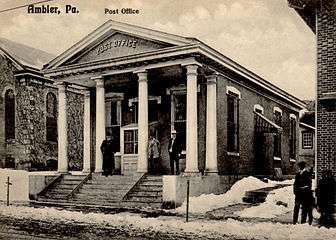

Opera House, 1906 Post office, 1906

Post office, 1906 Trinity Memorial Episcopal Church, 1906

Trinity Memorial Episcopal Church, 1906 First Presbyterian Church of Ambler

First Presbyterian Church of Ambler

Geography

Ambler is located at 40°9′18″N 75°13′13″W (40.155099, -75.220160).[39]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the borough has a total area of 0.8 square miles (2.1 km2), all of it land.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 251 | — | |

| 1890 | 1,073 | 327.5% | |

| 1900 | 1,884 | 75.6% | |

| 1910 | 2,649 | 40.6% | |

| 1920 | 3,094 | 16.8% | |

| 1930 | 3,944 | 27.5% | |

| 1940 | 3,953 | 0.2% | |

| 1950 | 4,565 | 15.5% | |

| 1960 | 6,765 | 48.2% | |

| 1970 | 7,800 | 15.3% | |

| 1980 | 6,628 | −15.0% | |

| 1990 | 6,609 | −0.3% | |

| 2000 | 6,426 | −2.8% | |

| 2010 | 6,417 | −0.1% | |

| Est. 2019 | 6,491 | [3] | 1.2% |

| Sources:[40][41] | |||

| Year | Republican | Democratic |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 27.8% 904 | 67.2% 2,182 |

| 2012 | 31.2% 959 | 67.3% 2,069 |

| 2008 | 30.8% 947 | 68.4% 2,099 |

| 2004 | 33.7% 989 | 65.7% 1,927 |

| 2000 | 35.1% 875 | 60.4% 1,464 |

As of the 2010 census, the borough was 76.5% White, 12.8% Black or African American, 0.2% Native American, 3.8% Asian, 0.3% Native Hawaiian, and 3.4% were two or more races. 7.9% were of Hispanic or Latino ancestry, an almost four-fold increase since the 2000 census .

As of the census[43] of 2000, there were 6,426 people, 2,510 households, and 1,598 families residing in the borough. The population density was 7,605.8 people per square mile (2,953.7/km2). There were 2,605 housing units at an average density of 3,083.3 per square mile (1,197.4/km2). The racial makeup of the borough was 83.29% White, 12.03% African American, 0.25% Native American, 2.47% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 0.50% from other races, and 1.40% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.13% of the population.

There were 2,510 households, out of which 29.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.7% were married couples living together, 13.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.3% were non-families. 30.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.45 and the average family size was 3.08.

In the borough the population was spread out, with 23.5% under the age of 18, 7.0% from 18 to 24, 32.5% from 25 to 44, 19.7% from 45 to 64, and 17.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37 years. For every 100 females there were 86.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 81.8 males.

The median income for a household in the borough was $47,014, and the median income for a family was $51,235. Males had a median income of $40,305 versus $30,735 for females. The per capita income for the borough was $21,688. About 2.4% of families and 5.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 6.8% of those under age 18 and 4.9% of those age 65 or over.

Politics and government

Ambler has a city manager form of government with a mayor and a nine-member borough council. The mayor is Jeanne Sorg.[44] The borough is part of the Fourth Congressional District (represented by Rep. Madeleine Dean), the 148th State House District (represented by Rep. Mary Jo Daley)[45] and the 12th State Senate District (represented by Sen. Maria Collett).

Education

The Borough of Ambler is served by the Wissahickon School District. In 2004, the Wissahickon School District had 4,535 students. Wissahickon School District has six schools: four elementary, one middle (grades 6-8) and one high school (grades 9-12).[46]

There is an area Catholic grade school, Our Lady of Mercy Regional Catholic School, in Maple Glen. Our Lady of Mercy was formed in 2012 by the merger of St. Anthony-St. Joseph in Ambler, St. Alphonsus in Maple Glen, and St. Catherine of Siena in Horsham.[47]

Temple University, whose main campus is in nearby urban Philadelphia, has a suburban campus that is referred to as the Ambler Campus.[48] The main contact address for the campus has an Ambler postal address, 580 Meetinghouse Road, Ambler, PA 19002.[49] However, it is technically outside the borough limits, in Upper Dublin Township,[50] and is in the purview of the Upper Dublin Township Police. Temple University Ambler was founded in 1910 as the Pennsylvania School of Horticulture for Women.[49] It offers an array of undergraduate, graduate, and non-credit programs.[51]

Arts and culture

Act II Playhouse

Act II Playhouse is a 130-seat professional theatre founded in 1998. Act II has been nominated for 31 Barrymore Awards and has won six.[52]

Ambler Symphony Orchestra

Founded in 1951, the Ambler Symphony Orchestra currently performs several concerts per year under the musical direction of WRTI program director Jack Moore.[53]

Ambler Theater

Originally opened in 1927 as a Warner Brothers movie theater, the recently restored and renovated Ambler Theater is a non-profit, community owned movie theater that shows independent, art and limited-distribution films.[54]

Post Office

Post office murals were produced from 1934 to 1943 in the United States through the Section of Painting and Sculpture, later called the Section of Fine Arts, of the Treasury Department. The murals were intended to boost the morale of the American people from the effects of the Depression by depicting uplifting subjects.[55] The murals were funded as a part of the cost of the construction or renovation with 1% of the cost set aside for artistic enhancements.[56] In 1939, artist Harry Sternberg completed the mural, The Family, Industry and Architecture for the town's post office. The artist and his family are the main figures in the painting.

People from Ambler

- John Di Domenico - Comedian, actor, and writer

Transportation

Butler Avenue serves as the main street through Ambler, with the road known as Butler Pike outside the borough. Butler Pike heads southwest to Plymouth Meeting and northeast to Horsham Township. Bethlehem Pike runs along the eastern border of Ambler and heads north to Montgomeryville and south to Philadelphia. Pennsylvania Route 309 passes to the east of Ambler on a freeway called the Fort Washington Expressway, with access to Ambler at a southbound exit and northbound entrance at Butler Pike and a northbound exit and southbound entrance at Susquehanna Road. The Pennsylvania Turnpike (Interstate 276) has an interchange with PA 309 south of Ambler in Fort Washington.[57]

Ambler is served by SEPTA Regional Rail's Lansdale/Doylestown Line, which provides service to Center City Philadelphia, Lansdale, Doylestown and other intermediate points, at the Ambler station, which is a major park-and-ride facility on the line. SEPTA Suburban Division bus routes 94 and 95 also serve Ambler, with Route 94 connecting Ambler to the Chestnut Hill section of Philadelphia and the Montgomery Mall and Route 95 connecting Ambler to Willow Grove and Gulph Mills.[58]

Sister cities

Ambler is a sister city with:

References

- P. H. Hough, Dr. Mary (1936). "Early history of Ambler". The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Introduction to the Lenni Lenape, or Delaware Indians". Penn Treaty Museum. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Newman, Andrew (2013). "Treaty of Shackamaxon". The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Rutgers University. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Myers, Albert Cook (1902). Quaker arrivals at Philadelphia, 1682-1750; being a list of certificates of removal received at Philadelphia monthly meeting of Friends,. Philadelphia: Ferris & Leach. pp. 5–6. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- "Ambler Open Space Plan". Montgomery County, PA. Ambler Borough. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Bean, Theodore Weber (1884). History of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: Everts & Peck. pp. 1092–1093.

- "The History of the Harmer-Morris-Detwiler-Zabriskie House". Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Quattrone, Frank D. (2004). Ambler. Portsmouth, NH: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0738534831.

- Hough, Mary Paul Hallowell (1936). Early History of Ambler, 1682-1888. Ambler, PA: Harry Hellar Kelly.

- Wiley, Samuel T. (1895). Biographical and portrait cyclopedia of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania : containing biographical sketches of prominent and representative citizens of the county, together with an introductory historical sketch. Philadelphia: Biographical Publishing Company. p. 571. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Mary Ambler and the Great Train Accident". The Borough of Ambler. Archived from the original on 2015-09-25. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Mary Johnson Ambler". Find A Grave. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Mary Ambler: Heroine of the Great Train Wreck". Historic Wissahickon Valley. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Dougherty, Bernadette (June 25, 2013). "Letter: Happy 125th birthday, Ambler!". Ambler Gazette. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- Kennedy, Joseph S. (September 5, 1999). "How A Physician Met A Pharmacist, Found A Fortune In Ambler Dr. Richard V. Mattison And Henry G. Keasbey Turned The Tiny Burg Into A Thriving Company Town". Philly.com. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- O'Hara, L. M. (2001). The town that asbestos built: The industrialization of Ambler, Pennsylvania (Honors Thesis). University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University.

- Toll, Jean Barth; Schwager, Michael J. (1983). Montgomery County, the second hundred years (1st ed.). Norristown, PA: Montgomery County Federation of Historical Societies. ISBN 9780961241827.

- "A History of Trinity Episcopal Church, Ambler: The first hundred years, 1898-1998" (PDF). Trinity Ambler. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- Conroy, Theresa; Price, Bill (June 17, 1986). "Fire Destroys Upper Dublin Church". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- Reiny, Samson (2015). "Living in the Town Asbestos Built". Distillations Magazine. 1 (2): 26–35. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- Ciccarelli, Maura C. (August 23, 1987). "When Man's Home Really Was His Castle". Philly.com. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- "Ambler forms twinship with Maida, Italy". Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- Burke, Richard (July 27, 1987). "A Bitter Legacy Left By Nicolet Asbestos Waste Stays In Ambler". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- Cooke WE (1924-07-26). "Fibrosis of the Lungs due to the Inhalation of Asbestos Dust". Br Med J. 2 (3317): 140–2, 147. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.3317.147. PMC 2304688. PMID 20771679.

- "National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan; National Priorities List" (PDF). Federal Register. U.S Government Printing Office. 61 (173). 5 September 1996.

- "The White Elephant". Distillations Magazine. 1 (3): 48. 2015.

- "Federal-Mogul Completes T&N Acquisition". PR Newswire. March 6, 1998. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Federal-Mogul Corporation Files Voluntary Chapter 11 And Administration Petitions to Resolve Asbestos Claims". Federal Mogul Press Release. October 1, 2001. Archived from the original on 17 November 2018. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "REACH Ambler: From factory to the future in Ambler, Pennsylvania". REACH Ambler. Science History Institute. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- "Ambler Asbestos Piles". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- "BoRit Asbestos Site". United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- Mercier, Dominic (March 29, 2013). "Generating New Life At The Ambler Boiler House". Hidden City Philadelphia. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Moon, Robert C. (1908). The Morris family of Philadelphia; descendants of Anthony Morris, born 1654-1721 died. 4. Philadelphia: R. C. Moon. pp. 156–157.

- Kenna, Eileen (March 7, 1991). "Ambler Firm's Legacy Is Town's Victorian Jewels". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Finarelli, Linda (April 28, 2015). "Lindenwold Castle anticipated centerpiece of development". Ambler Gazette. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "Census of Population and Housing: Decennial Censuses". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-03-04.

- "Incorporated Places and Minor Civil Divisions Datasets: Subcounty Resident Population Estimates: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012". Population Estimates. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 11 June 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "Montgomery County Election Results". Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. Retrieved January 16, 2017.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Ambler Borough Council". The Borough of Ambler. Archived from the original on 2015-09-26. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- "Mary Jo Daley". Pennsylvania House of Representatives. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- "District Background". Wissahickon School District. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- "2012 Catholic grade school consolidations/closings". Catholicphilly.com. 2012-07-15. Retrieved 2020-04-22.

- "Ambler Campus". Temple University. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- "History The Historic Ambler Campus". Temple University. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- Sokil, Dan (July 9, 2010). "Temple Ambler campus housing closes". The Reporter News. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- "Degree Programs". Ambler Campus. Temple University. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- "Our Mission". Act II Playhouse. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- "About". Ambler Symphony Orchestra. Retrieved 26 September 2015.

- "History Since 1928". Ambler Theater, Inc. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Rediscovering the People's Art: New Deal Murals in Pennsylvania’s Post Offices". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission: 2014.

- University of Central Arkansas. "Arkansas Post Office Murals".

- Montgomery County, Pennsylvania (Map) (18th ed.). 1"=2000'. ADC Map. 2006. ISBN 0-87530-775-2.

- SEPTA Official Transit & Street Map Suburban (PDF) (Map). SEPTA. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ambler, Pennsylvania. |