Hyaluronic acid

Hyaluronic acid (/ˌhaɪ.əljʊəˈrɒnɪk/[2][3]; abbreviated HA; conjugate base hyaluronate), also called hyaluronan, is an anionic, nonsulfated glycosaminoglycan distributed widely throughout connective, epithelial, and neural tissues. It is unique among glycosaminoglycans in that it is nonsulfated, forms in the plasma membrane instead of the Golgi apparatus, and can be very large: human synovial HA averages about 7 million Da per molecule, or about 20000 disaccharide monomers,[4] while other sources mention 3–4 million Da.[5] As one of the chief components of the extracellular matrix, hyaluronan contributes significantly to cell proliferation and migration, and may also be involved in the progression of some malignant tumors.[6]

| |

Haworth projection | |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| |

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.029.695 |

| EC Number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| Properties | |

| (C14H21NO11)n | |

| Soluble (sodium salt) | |

| Pharmacology | |

| D03AX05 (WHO) M09AX01 (WHO), R01AX09 (WHO), S01KA01 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| S-phrases (outdated) | S22, S24/25 (sodium salt) |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose) |

> 2400 mg/kg (mouse, oral, sodium salt) 4000 mg/kg (mouse, subcutaneous, sodium salt) 1500 mg/kg (mouse, intraperitoneal, sodium salt)[1] |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds |

D-Glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (monomers) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

The average 70 kg (154 lb) person has roughly 15 grams of hyaluronan in the body, one-third of which is turned over (degraded and synthesized) every day.[7] Hyaluronic acid is also a component of the group A streptococcal extracellular capsule,[8] and is believed to play a role in virulence.[9][10]

Physiological function

Until the late 1970s, hyaluronic acid was described as a "goo" molecule, a ubiquitous carbohydrate polymer that is part of the extracellular matrix.[11] For example, hyaluronic acid is a major component of the synovial fluid, and was found to increase the viscosity of the fluid. Along with lubricin, it is one of the fluid's main lubricating components.

Hyaluronic acid is an important component of articular cartilage, where it is present as a coat around each cell (chondrocyte). When aggrecan monomers bind to hyaluronan in the presence of HAPLN1 (hyaluronanic acid and proteoglycan link protein 1), large, highly negatively charged aggregates form. These aggregates imbibe water and are responsible for the resilience of cartilage (its resistance to compression). The molecular weight (size) of hyaluronan in cartilage decreases with age, but the amount increases.[12]

A lubricating role of hyaluronan in muscular connective tissues to enhance the sliding between adjacent tissue layers has been suggested. A particular type of fibroblasts, embedded in dense fascial tissues, has been proposed as being cells specialized for the biosynthesis of the hyaluronan-rich matrix. Their related activity could be involved in regulating the sliding ability between adjacent muscular connective tissues.[13]

Hyaluronic acid is also a major component of skin, where it is involved in tissue repair. When skin is exposed to excessive UVB rays, it becomes inflamed (sunburn) and the cells in the dermis stop producing as much hyaluronan, and increase the rate of its degradation. Hyaluronan degradation products then accumulate in the skin after UV exposure.[14]

While it is abundant in extracellular matrices, hyaluronan also contributes to tissue hydrodynamics, movement and proliferation of cells, and participates in a number of cell surface receptor interactions, notably those including its primary receptors, CD44 and RHAMM. Upregulation of CD44 itself is widely accepted as a marker of cell activation in lymphocytes. Hyaluronan's contribution to tumor growth may be due to its interaction with CD44. Receptor CD44 participates in cell adhesion interactions required by tumor cells.

Although hyaluronan binds to receptor CD44, there is evidence hyaluronan degradation products transduce their inflammatory signal through toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), TLR4, or both TLR2 and TLR4 in macrophages and dendritic cells. TLR and hyaluronan play a role in innate immunity.

There are limitations including the in vivo loss of this compound limiting the duration of effect.[15]

Wound repair

Hyaluronic acid is a main component of the extracellular matrix, and has a key role in tissue regeneration, inflammation response, and angiogenesis, which are phases of skin wound repair.[16] As of 2016, reviews assessing its effect to promote wound healing, however, show only limited evidence from clinical research to affect burns, diabetic foot ulcers, or surgical skin repairs.[16] In gel form, hyaluronic acid combines with water and swells, making it useful in skin treatments as a dermal filler for treating facial wrinkles and lasting some 6 to 12 months, a clinical treatment with regulatory approval by the US Food and Drug Administration.[17]

Granulation

Granulation tissue is the perfused, fibrous connective tissue that replaces a fibrin clot in healing wounds. It typically grows from the base of a wound and is able to fill wounds of almost any size it heals. HA is abundant in granulation tissue matrix. A variety of cell functions that are essential for tissue repair may attribute to this HA-rich network. These functions include facilitation of cell migration into the provisional wound matrix, cell proliferation and organization of the granulation tissue matrix.[18] Initiation of inflammation is crucial for the formation of granulation tissue; therefore, the pro-inflammatory role of HA as discussed above also contributes to this stage of wound healing.[18]

Cell migration

Cell migration is essential for the formation of granulation tissue.[18] The early stage of granulation tissue is dominated by a HA-rich extracellular matrix, which is regarded as a conducive environment for migration of cells into this temporary wound matrix. Contributions of HA to cell migration may attribute to its physicochemical properties as stated above, as well as its direct interactions with cells. For the former scenario, HA provides an open hydrated matrix that facilitates cell migration,[18] whereas, in the latter scenario, directed migration and control of the cell locomotory mechanisms are mediated via the specific cell interaction between HA and cell surface HA receptors. As discussed before, the three principal cell surface receptors for HA are CD44, RHAMM, and ICAM-1. RHAMM is more related to cell migration. It forms links with several protein kinases associated with cell locomotion, for example, extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase (ERK), p125fak, and pp60c-src.[19][20][21] During fetal development, the migration path through which neural crest cells migrate is rich in HA.[18] HA is closely associated with the cell migration process in granulation tissue matrix, and studies show that cell movement can be inhibited, at least partially, by HA degradation or blocking HA receptor occupancy.[22]

By providing the dynamic force to the cell, HA synthesis has also been shown to associate with cell migration.[23] Basically, HA is synthesized at the plasma membrane and released directly into the extracellular environment.[18] This may contribute to the hydrated microenvironment at sites of synthesis, and is essential for cell migration by facilitating cell detachment.

Skin healing

HA plays an important role in the normal epidermis. HA also has crucial functions in the reepithelization process due to several of its properties. These include being an integral part of the extracellular matrix of basal keratinocytes, which are major constituents of the epidermis; its free-radical scavenging function and its role in keratinocyte proliferation and migration.[18]

In normal skin, HA is found in relatively high concentrations in the basal layer of the epidermis where proliferating keratinocytes are found.[24] CD44 is collocated with HA in the basal layer of epidermis where additionally it has been shown to be preferentially expressed on plasma membrane facing the HA-rich matrix pouches.[18][25] Maintaining the extracellular space and providing an open, as well as hydrated, structure for the passage of nutrients are the main functions of HA in epidermis. A report found HA content increases in the presence of retinoic acid (vitamin A).[24] The proposed effects of retinoic acid against skin photo-damage and aging may be correlated, at least in part, with an increase of skin HA content, giving rise to increase of tissue hydration. It has been suggested that the free-radical scavenging property of HA contributes to protection against solar radiation, supporting the role of CD44 acting as a HA receptor in the epidermis.[18]

Epidermal HA also functions as a manipulator in the process of keratinocyte proliferation, which is essential in normal epidermal function, as well as during reepithelization in tissue repair. In the wound healing process, HA is expressed in the wound margin, in the connective tissue matrix, and collocating with CD44 expression in migrating keratinocytes.[18][26] Kaya et al. found suppression of CD44 expression by an epidermis-specific antisense transgene resulted in animals with defective HA accumulation in the superficial dermis, accompanied by distinct morphologic alterations of basal keratinocytes and defective keratinocyte proliferation in response to mitogen and growth factors. Decrease in skin elasticity, impaired local inflammatory response, and impaired tissue repair were also observed.[18] Their observations are strongly supportive of the important roles HA and CD44 have in skin physiology and tissue repair.[18]

Medical uses

Hyaluronic acid has been FDA-approved to treat osteoarthritis of the knee via intra-articular injection.[27] A 2012 review showed that the quality of studies supporting this use was mostly poor, with general absence of significant benefit, and intra-articular injection of hyaluronic acid could possibly cause adverse effects.[28] A 2020 meta-analysis found that intra-articular injection of high molecular weight hyaluronic acid improved both pain and function in people with knee osteoarthritis.[29]

Dry, scaly skin, such as that caused by atopic dermatitis, may be treated with skin lotion containing sodium hyaluronate as its active ingredient.[30] Hyaluronic acid has been used in various formulations to create artificial tears to treat dry eye.[31]

Hyaluronic acid is a common ingredient in skin care products. Hyaluronic acid is used as a dermal filler in cosmetic surgery.[32] It is typically injected using either a classic sharp hypodermic needle or a micro-cannula. Complications include the severing of nerves and microvessels, pain, and bruising. In some cases, hyaluronic acid fillers result in a granulomatous foreign body reaction.[33]

Structure

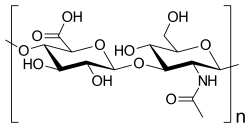

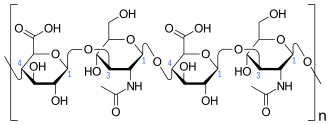

Hyaluronic acid is a polymer of disaccharides, themselves composed of D-glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, linked via alternating β-(1→4) and β-(1→3) glycosidic bonds. Hyaluronic acid can be 25,000 disaccharide repeats in length. Polymers of hyaluronic acid can range in size from 5,000 to 20,000,000 Da in vivo. The average molecular weight in human synovial fluid is 3–4 million Da, and hyaluronic acid purified from human umbilical cord is 3,140,000 Da;[5] other sources mention average molecular weight of 7 million Da for synovial fluid.[4] Hyaluronic acid also contains silicon, ranging between 350μg/g to 1900μg/g depending on location in the organism.[34]

Hyaluronic acid is energetically stable, in part because of the stereochemistry of its component disaccharides. Bulky groups on each sugar molecule are in sterically favored positions, whereas the smaller hydrogens assume the less-favorable axial positions.

Biological synthesis

Hyaluronic acid is synthesized by a class of integral membrane proteins called hyaluronan synthases, of which vertebrates have three types: HAS1, HAS2, and HAS3. These enzymes lengthen hyaluronan by repeatedly adding glucuronic acid and N-acetylglucosamine to the nascent polysaccharide as it is extruded via ABC-transporter through the cell membrane into the extracellular space.[35] The term fasciacyte was coined to describe fibroblast-like cells that synthesize HA.[36][37]

Hyaluronic acid synthesis has been shown to be inhibited by 4-methylumbelliferone (hymecromone, heparvit), a 7-hydroxy-4-methylcoumarin derivative.[38] This selective inhibition (without inhibiting other glycosaminoglycans) may prove useful in preventing metastasis of malignant tumor cells.[39] There is feedback inhibition of hyaluronan synthesis by low molecular weight hyaluronan (<500kDa) at high concentrations but stimulation by high molecular weight (>500kDa) HA when tested in cultured human synovial fibroblasts.[40]

Bacillus subtilis recently has been genetically modified to culture a proprietary formula to yield hyaluronans,[41] in a patented process producing human-grade product.

Fasciacyte

A fasciacyte is a type of biological cell that produces hyaluronan-rich extracellular matrix, and modulates the gliding of muscle fasciae.[36]

Fasciacytes are fibroblast-like cells found in fasciae. They are round-shaped with rounder nuclei, and have less elongated cellular processes when compared with fibroblasts. Fasciacytes are clustered along the upper and lower surfaces of a fascial layer.

Fasciacytes produce hyaluronan, which regulates fascial gliding.[36]

Degradation

Hyaluronic acid can be degraded by a family of enzymes called hyaluronidases. In humans, there are at least seven types of hyaluronidase-like enzymes, several of which are tumor suppressors. The degradation products of hyaluronan, the oligosaccharides and very low-molecular-weight hyaluronan, exhibit pro-angiogenic properties.[42] In addition, recent studies showed hyaluronan fragments, not the native high-molecular weight molecule, can induce inflammatory responses in macrophages and dendritic cells in tissue injury and in skin transplant.[43][44]

Hyaluronic acid can also be degraded via non-enzymatic reactions. These include acidic and alkaline hydrolysis, ultrasonic disintegration, thermal decomposition, and degradation by oxidants.[45]

Cell receptors for hyaluronic acid

So far, cell receptors that have been identified for HA fall into three main groups: CD44, Receptor for HA-mediated motility (RHAMM) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1). CD44 and ICAM-1 were already known as cell adhesion molecules with other recognized ligands before their HA binding properties were discovered.[46]

CD44 is widely distributed throughout the body, and the formal demonstration of HA-CD44 binding was proposed by Aruffo et al.[47] in 1990. To date, it is recognized as the main cell surface receptor for HA. CD44 mediates cell interaction with HA and the binding of the two functions as an important part in various physiologic events,[18][46] such as cell aggregation, migration, proliferation and activation; cell–cell and cell–substrate adhesion; endocytosis of HA, which leads to HA catabolism in macrophages; and assembly of pericellular matrices from HA and proteoglycan. Two significant roles of CD44 in skin were proposed.[26] The first is regulation of keratinocyte proliferation in response to extracellular stimuli, and the second is the maintenance of local HA homeostasis.[18]

ICAM-1 is known mainly as a metabolic cell surface receptor for HA, and this protein may be responsible mainly for the clearance of HA from lymph and blood plasma, which accounts for perhaps most of its whole-body turnover.[46][48] Ligand binding of this receptor, thus, triggers a highly coordinated cascade of events that includes the formation of an endocytotic vesicle, its fusion with primary lysosomes, enzymatic digestion to monosaccharides, active transmembrane transport of these sugars to cell sap, phosphorylation of GlcNAc and enzymatic deacetylation.[46][49][50] Like its name, ICAM-1 may also serve as a cell adhesion molecule, and the binding of HA to ICAM-1 may contribute to the control of ICAM-1-mediated inflammatory activation.[18]

Etymology

Hyaluronic acid is derived from hyalos (Greek for vitreous, meaning ‘glass-like’) and uronic acid because it was first isolated from the vitreous humour and possesses a high uronic acid content.

The term hyaluronate refers to the conjugate base of hyaluronic acid. Because the molecule typically exists in vivo in its polyanionic form, it is most commonly referred to as hyaluronan.

History

Hyaluronic acid was first obtained by Karl Meyer and John Palmer in 1934 from the vitreous body in the cow's eye.[51] The first hyaluronan biomedical product, Healon, was developed in the 1970s and 1980s by Pharmacia, and approved for use in eye surgery (i.e., corneal transplantation, cataract surgery, glaucoma surgery, and surgery to repair retinal detachment). Other biomedical companies also produce brands of hyaluronan for ophthalmic surgery.

Native hyaluronic acid has a relatively short half-life (shown in rabbits)[52] so various manufacturing techniques have been deployed to extend the length of the chain and stabilise the molecule for its use in medical applications. The introduction of protein-based cross-links,[53] the introduction of free-radical scavenging molecules such as sorbitol,[54] and minimal stabilisation of the HA chains through chemical agents such as NASHA (non-animal stabilised hyaluronic acid)[55] are all techniques that have been used.[56]

In the late 1970s, intraocular lens implantation was often followed by severe corneal edema, due to endothelial cell damage during the surgery. It was evident that a viscous, clear, physiologic lubricant to prevent such scraping of the endothelial cells was needed.[57][58]

The name "hyaluronan" is also used to infer a salt.[59]

Other animals

Hyaluronan is used in treatment of articular disorders in horses, in particular those in competition or heavy work. It is indicated for carpal and fetlock joint dysfunctions, but not when joint sepsis or fracture are suspected. It is especially used for synovitis associated with equine osteoarthritis. It can be injected directly into an affected joint, or intravenously for less localized disorders. It may cause mild heating of the joint if directly injected, but this does not affect the clinical outcome. Intra-articularly administered medicine is fully metabolized in less than a week.[60]

Note that, according to Canadian regulation, hyaluronan in HY-50 preparation should not be administered to animals to be slaughtered for horse meat.[61] In Europe, however, the same preparation is not considered to have any such effect, and edibility of the horse meat is not affected.[62]

Naked mole rats have very high molecular weight hyaluronan (6–12 MDa) that has been shown to give them resistance to cancer.[63] This large HA is due to both differently sequenced HAS2 and lower HA degradation mechanisms.

Research

Due to its high biocompatibility and its common presence in the extracellular matrix of tissues, hyaluronan is gaining popularity as a biomaterial scaffold in tissue engineering research.[64][65][66] In particular, a number of research groups have found hyaluronan's properties for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine are significantly improved with crosslinking, producing a hydrogel. The pioneering work on crosslinked hyaluronan derivatives was initiated by a small research group headed by Prof. Aurelio Romeo[67] in the late 1980s.[68][69] Crosslinking allows a researcher to form a desired shape, as well as to deliver therapeutic molecules, into a host.[70] Hyaluronan can be crosslinked by attaching thiols (trade names: Extracel, HyStem),[70] methacrylates,[71] hexadecylamides (trade name: Hymovis),[72] and tyramines (trade name: Corgel).[73] Hyaluronan can also be crosslinked directly with formaldehyde (trade name: Hylan-A) or with divinylsulfone (trade name: Hylan-B).[74]

Due to its ability to regulate angiogenesis by stimulating endothelial cells to proliferate, hyaluronan can be used to create hydrogels to study vascular morphogenesis.[75] These hydrogels have properties similar to human soft tissue, but are also easily controlled and modified, making HA very suitable for tissue-engineering studies. For example, HA hydrogels are appealing for engineering vasculature from endothelial progenitor cells by using appropriate growth factors such as VEGF and Ang-1 to promote proliferation and vascular network formation. Vacuole and lumen formation have been observed in these gels, followed by branching and sprouting through degradation of the hydrogel and finally complex network formation. The ability to generate vascular networks using HA hydrogels leads to opportunities for in vivo and clinical applications. One in vivo study, where HA hydrogels with endothelial colony forming cells were implanted into mice three days after hydrogel formation, saw evidence that the host and engineered vessels joined within 2 weeks of implantation, indicating viability and functionality of the engineered vasculature.[76]

See also

References

- Hyaluronate Sodium in the ChemIDplus database, consulté le 12 février 2009

- https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/hyaluronic_acid

- https://www.wordreference.com/definition/Hyaluronic%20acid

- Fraser JR, Laurent TC, Laurent UB (1997). "Hyaluronan: its nature, distribution, functions and turnover". J. Intern. Med. 242 (1): 27–33. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.00170.x. PMID 9260563.

- Saari H, Konttinen YT, Friman C, Sorsa T (1993). "Differential effects of reactive oxygen species on native synovial fluid and purified human umbilical cord hyaluronate". Inflammation. 17 (4): 403–15. doi:10.1007/bf00916581. PMID 8406685.

- Stern, edited by Robert (2009). Hyaluronan in cancer biology (1st ed.). San Diego, CA: Academic Press/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-12-374178-3.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Stern R (2004). "Hyaluronan catabolism: a new metabolic pathway". Eur. J. Cell Biol. 83 (7): 317–25. doi:10.1078/0171-9335-00392. PMID 15503855.

- Sugahara K, Schwartz NB, Dorfman A (1979). "Biosynthesis of hyaluronic acid by Streptococcus" (PDF). J. Biol. Chem. 254 (14): 6252–6261. PMID 376529.

- Wessels MR, Moses AE, Goldberg JB, DiCesare TJ (1991). "Hyaluronic acid capsule is a virulence factor for mucoid group A streptococci" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 88 (19): 8317–8321. doi:10.1073/pnas.88.19.8317. PMC 52499. PMID 1656437.

- Schrager HM, Rheinwald JG, Wessels MR (1996). "Hyaluronic acid capsule and the role of streptococcal entry into keratinocytes in invasive skin infection". J. Clin. Invest. 98 (9): 1954–1958. doi:10.1172/JCI118998. PMC 507637. PMID 8903312.

- Toole BP (2000). "Hyaluronan is not just a goo!". J. Clin. Invest. 106 (3): 335–336. doi:10.1172/JCI10706. PMC 314333. PMID 10930435.

- Holmes MW, et al. (1988). "Hyaluronic acid in human articular cartilage. Age-related changes in content and size". Biochem. J. 250 (2): 435–441. doi:10.1042/bj2500435. PMC 1148875. PMID 3355532.

- Stecco C, Stern R, Porzionato A, Macchi V, Masiero S, Stecco A, De Caro R (2011). "Hyaluronan within fascia in the etiology of myofascial pain". Surg Radiol Anat. 33 (10): 891–6. doi:10.1007/s00276-011-0876-9. PMID 21964857.

- Averbeck M, Gebhardt CA, Voigt S, Beilharz S, Anderegg U, Termeer CC, Sleeman JP, Simon JC (2007). "Differential regulation of hyaluronan metabolism in the epidermal and dermal compartments of human skin by UVB irradiation". J. Invest. Dermatol. 127 (3): 687–97. doi:10.1038/sj.jid.5700614. PMID 17082783.

- "Synvisc-One (hylan GF-20) – P940015/S012". Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2014-11-23.

- Shaharudin, A.; Aziz, Z. (2 October 2016). "Effectiveness of hyaluronic acid and its derivatives on chronic wounds: a systematic review". Journal of Wound Care. 25 (10): 585–592. doi:10.12968/jowc.2016.25.10.585. ISSN 0969-0700. PMID 27681589.

- "Dermal Fillers Approved by the Center for Devices and Radiological Health". U S Food and Drug Administration. 26 November 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- Chen WYJ, Abatangelo G (1999). "Functions of hyaluronan in wound repair". Wound Repair Regen. 7 (2): 79–89. doi:10.1046/j.1524-475x.1999.00079.x. PMID 10231509.

- Hardwick C, Hoare K, Owens R, Hohn HP, Hook M, Moore D, Cripps V, Austen L, Nance DM, Turley EA (1992). "Molecular cloning of a novel hyaluronan receptor that mediates tumor cell motility". J. Cell Biol. 117 (6): 1343–50. doi:10.1083/jcb.117.6.1343. PMC 2289508. PMID 1376732.

- Wang C, Thor AD, Moore DH, Zhao Y, Kerschmann R, Stern R, Watson PH, Turley EA (1998). "The overexpression of RHAMM, a hyaluronan-binding protein that regulates ras signaling, correlates with overexpression of mitogen-activated protein kinase and is a significant parameter in breast cancer progression". Clin. Cancer Res. 4 (3): 567–76. PMID 9533523.

- Hall CL, Lange LA, Prober DA, Zhang S, Turley EA (1996). "pp60(c-src) is required for cell locomotion regulated by the hyaluronanreceptor RHAMM". Oncogene. 13 (10): 2213–24. PMID 8950989.

- Morriss-Kay GM, Tuckett F, Solursh M (1986). "The effects of Streptomyces hyaluronidase on tissue organization and cell cycle time in rat embryos". J Embryol Exp Morphol. 98: 59–70. PMID 3655652.

- Ellis IR, Schor SL (1996). "Differential effects of TGF-beta1 on hyaluronan synthesis by fetal and adult skin fibroblasts: implications for cell migration and wound healing". Exp. Cell Res. 228 (2): 326–33. doi:10.1006/excr.1996.0332. PMID 8912726.

- Tammi R, Ripellino JA, Margolis RU, Maibach HI, Tammi M (1989). "Hyaluronate accumulation in human epidermis treated with retinoic acid in skin organ culture". J. Invest. Dermatol. 92 (3): 326–32. doi:10.1111/1523-1747.ep12277125. PMID 2465358.

- Tuhkanen AL, Tammi M, Pelttari A, Agren UM, Tammi R (1998). "Ultrastructural analysis of human epidermal CD44 reveals preferential distribution on plasma membrane domains facing the hyaluronan-rich matrix pouches". J. Histochem. Cytochem. 46 (2): 241–8. doi:10.1177/002215549804600213. PMID 9446831.

- Kaya, G; Rodriguez, I; Jorcano, J L; Vassalli, P; Stamenkovic, I (1997). "Selective suppression of CD44 in keratinocytes of mice bearing an antisense CD44 transgene driven by a tissue-specific promoter disrupts hyaluronate metabolism in the skin and impairs keratinocyte proliferation". Genes & Development. 11 (8): 996–1007. doi:10.1101/gad.11.8.996. ISSN 0890-9369. PMID 9136928.

- Timothy Gower. "Hyaluronic acid injections for osteoarthritis". US Arthritis Foundation. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Rutjes AW, Jüni P, da Costa BR, Trelle S, Nüesch E, Reichenbach S (2012). "Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Ann. Intern. Med. 157 (3): 180–91. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-3-201208070-00473. PMID 22868835.

- Mark Phillips, Christopher Vannabouathong, Tahira Devji, Rahil Patel, Zoya Gomes, Ashaka Patel, Mykaelah Dixon, Mohit Bhandari (2020). "Differentiating factors of intra‑articular injectables have a meaningful impact on knee osteoarthritis outcomes: a network meta‑analysis". Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. doi:10.1007/s00167-019-05763-1. PMID 31897550.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Hylira gel: Indications, Side Effects, Warnings". Drugs.com. 14 February 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Pucker AD, Ng SM, Nichols JJ (2016). "Over the counter (OTC) artificial tear drops for dry eye syndrome". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2: CD009729. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009729.pub2. PMC 5045033. PMID 26905373.

- "Hyaluronic Acid: Uses, Side Effects, Interactions, Dosage, and Warning". WebMD. 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Edwards, PC; Fantasia, JE (2007). "Review of long-term adverse effects associated with the use of chemically-modified animal and nonanimal source hyaluronic acid dermal fillers". Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2 (4): 509–19. doi:10.2147/cia.s382. PMC 2686337. PMID 18225451.

- Schwarz, K. (1973-05-01). "A bound form of silicon in glycosaminoglycans and polyuronides". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 70 (5): 1608–1612. doi:10.1073/pnas.70.5.1608. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 433552. PMID 4268099.

- Schulz T, Schumacher U, Prehm P (2007). "Hyaluronan export by the ABC transporter MRP5 and its modulation by intracellular cGMP". J. Biol. Chem. 282 (29): 20999–1004. doi:10.1074/jbc.M700915200. PMID 17540771.

- Stecco, Carla; Fede, Caterina; Macchi, Veronica; Porzionato, Andrea; Petrelli, Lucia; Biz, Carlo; Stern, Robert; De Caro, Raffaele (2018-04-14). "The fasciacytes: A new cell devoted to fascial gliding regulation". Clinical Anatomy. 31 (5): 667–676. doi:10.1002/ca.23072. ISSN 0897-3806. PMID 29575206.

- Stecco, Carla; Stern, R.; Porzionato, A.; Macchi, V.; Masiero, S.; Stecco, A.; De Caro, R. (2011-10-02). "Hyaluronan within fascia in the etiology of myofascial pain". Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy. 33 (10): 891–896. doi:10.1007/s00276-011-0876-9. ISSN 0930-1038. PMID 21964857.

- Kakizaki I, Kojima K, Takagaki K, Endo M, Kannagi R, Ito M, Maruo Y, Sato H, Yasuda T, et al. (2004). "A novel mechanism for the inhibition of hyaluronan biosynthesis by 4-methylumbelliferone". J. Biol. Chem. 279 (32): 33281–33289. doi:10.1074/jbc.M405918200. PMID 15190064.

- Yoshihara S, Kon A, Kudo D, Nakazawa H, Kakizaki I, Sasaki M, Endo M, Takagaki K (2005). "A hyaluronan synthase suppressor, 4-methylumbelliferone, inhibits liver metastasis of melanoma cells". FEBS Lett. 579 (12): 2722–6. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2005.03.079. PMID 15862315.

- Smith, MM; Ghosh, P (1987). "The synthesis of hyaluronic acid by human synovial fibroblasts is influenced by the nature of the hyaluronate in the extracellular environment". Rheumatol Int. 7 (3): 113–22. doi:10.1007/bf00270463. PMID 3671989.

- "Novozymes Biopharma | Produced without the use of animal-derived materials or solvents". Archived from the original on 2010-09-15. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

- Matou-Nasri S, Gaffney J, Kumar S, Slevin M (2009). "Oligosaccharides of hyaluronan induce angiogenesis through distinct CD44 and RHAMM-mediated signalling pathways involving Cdc2 and gamma-adducin". Int. J. Oncol. 35 (4): 761–773. doi:10.3892/ijo_00000389. PMID 19724912.

- Yung S, Chan TM (2011). "Pathophysiology of the peritoneal membrane during peritoneal dialysis: the role of hyaluronan". J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011: 1–11. doi:10.1155/2011/180594. PMC 3238805. PMID 22203782.

- Tesar BM, Jiang D, Liang J, Palmer SM, Noble PW, Goldstein DR (2006). "The role of hyaluronan degradation products as innate alloimmune agonists". Am. J. Transplant. 6 (11): 2622–2635. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01537.x. PMID 17049055.

- Stern, Robert; Kogan, Grigorij; Jedrzejas, Mark J.; Šoltés, Ladislav (1 November 2007). "The many ways to cleave hyaluronan". Biotechnology Advances. 25 (6): 537–557. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2007.07.001. PMID 17716848.

- Wayne D. Comper, Extracellular Matrix Volume 2 Molecular Components and Interactions, 1996, Harwood Academic Publishers

- Aruffo A, Stamenkovic I, Melnick M, Underhill CB, Seed B (1990). "CD44 is the principal cell surface receptor for hyaluronate". Cell. 61 (7): 1303–13. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(90)90694-a. PMID 1694723.

- Laurent UB, Reed RK (1991). "Turnover of hyaluronan in the tissues". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 7 (2): 237–256. doi:10.1016/0169-409x(91)90004-v.

- Fraser JR, Kimpton WG, Laurent TC, Cahill RN, Vakakis N (1988). "Uptake and degradation of hyaluronan in lymphatic tissue". Biochem. J. 256 (1): 153–8. doi:10.1042/bj2560153. PMC 1135381. PMID 3223897.

- Campbell P, Thompson JN, Fraser JR, Laurent TC, Pertoft H, Rodén L (1990). "N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase in hepatocytes, Kupffer cells and sinusoidal endothelial cells from rat liver". Hepatology. 11 (2): 199–204. doi:10.1002/hep.1840110207. PMID 2307398.

- Necas J, Bartosikova L, Brauner P, Kolar J (5 September 2008). "Hyaluronic acid (hyaluronan): a review". Veterinární Medicína. 53 (8): 397–411. doi:10.17221/1930-VETMED.

- Brown TJ, Laurent UB, Fraser JR (1991). "Turnover of hyaluronan in synovial joints: elimination of labelled hyaluronan from the knee joint of the rabbit". Exp. Physiol. 76 (1): 125–134. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.1991.sp003474. PMID 2015069.

- Frampton JE (2010). "Hylan G-F 20 single-injection formulation". Drugs Aging. 27 (1): 77–85. doi:10.2165/11203900-000000000-00000. PMID 20030435.

- Anteis | Change starts here

- Avantaggiato, A; Girardi, A; Palmieri, A; Pascali, M; Carinci, F (August 2015). "Bio-Revitalization: Effects of NASHA on Genes Involving Tissue Remodeling". Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. 39 (4): 459–64. doi:10.1007/s00266-015-0514-8. PMID 26085225.

- Medicijnvrije behandeling van artrose en artritis

- Miller, D.; O'Connor, P.; William, J. (1977). "Use of Na-Hyaluronate during intraocular lens implantation in rabbits". Ophthal. Surg. 8: 58–61.

- Miller, D.; Stegmann, R. (1983). Healon: A Comprehensive Guide to its Use in Ophthalmic Surgery. New York: J Wiley.

- John H. Brekke; Gregory E. Rutkowski; Kipling Thacker (2011). "Chapter 19 Hyaluronan". In Jeffrey O. Hollinger (ed.). An Introduction to Biomaterials (2nd ed.).

- Genitrix HY-50 Vet datasheet

- HY-50 for veterinary use Archived June 7, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Genitrix HY-50 Vet brochure Archived June 1, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Tian X, Azpurua J, Hine C, Vaidya A, Myakishev-Rempel M, Ablaeva J, Mao Z, Nevo E, Gorbunova V, Seluanov A (2013). "High-molecular-mass hyaluronan mediates the cancer resistance of the naked mole rat". Nature. 499 (7458): 346–9. doi:10.1038/nature12234. PMC 3720720. PMID 23783513.

- Segura T, Anderson BC, Chung PH, Webber RE, Shull KR, Shea LD (2005). "Crosslinked hyaluronic acid hydrogels: a strategy to functionalize and pattern". Biomaterials. 26 (4): 359–71. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.067. PMID 15275810.

- Segura T, Anderson BC, Chung PH, Webber RE, Shull KR, Shea LD (2005). "Crosslinked hyaluronic acid hydrogels: a strategy to functionalize and pattern" (PDF). Biomaterials. 26 (4): 359–71. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.02.067. PMID 15275810. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-25.

- Bio-skin FAQ

- it:Aurelio Romeo

- Della Valle F, Romeo A (1987). "New polysaccharide esters and their salts". Eur.Pat. Appl. EP0216453 A2 19870401.

- Della Valle F, Romeo A (1989). "Crosslinked carboxy polysaccharides". Eur. Pat. Appl. EP0341745 A1 19891115.

- Zheng Shu X, Liu Y, Palumbo FS, Luo Y, Prestwich GD (2004). "In situ crosslinkable hyaluronan hydrogels for tissue engineering". Biomaterials. 25 (7–8): 1339–48. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.08.014. PMID 14643608.

- Gerecht S, Burdick JA, Ferreira LS, Townsend SA, Langer R, Vunjak-Novakovic G (2007). "Hyaluronic acid hydrogel for controlled self-renewal and differentiation of human embryonic stem cells". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (27): 11298–303. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703723104. PMC 2040893. PMID 17581871.

- Smith MM, Russell AK, Schiavinato A, Little CB (2013). "A hexadecylamide derivative of hyaluronan (HYMOVIS®) has superior beneficial effects on human osteoarthritic chondrocytes and synoviocytes than unmodified hyaluronan". J Inflamm (Lond). 10: 26. doi:10.1186/1476-9255-10-26. PMC 3727958. PMID 23889808.

- Dar A, Calabro A: Synthesis and characterization of tyramine-based hyaluronan hydrogels. J Mater Sci: Mater Med, 20:33–44, 2009.

- Wnek GE, Bowlin GL, eds. (2008). Encyclopedia of Biomaterials and Biomedical Engineering. Informa Healthcare.

- Genasetti A, Vigetti D, Viola M, Karousou E, Moretto P, Rizzi M, Bartolini B, Clerici M, Pallotti F, De Luca G, Passi A (2008). "Hyaluronan and human endothelial cell behavior". Connect. Tissue Res. 49 (3): 120–3. doi:10.1080/03008200802148462. PMID 18661325.

- Hanjaya-Putra D, Bose V, Shen YI, Yee J, Khetan S, Fox-Talbot K, Steenbergen C, Burdick JA, Gerecht S (2011). "Controlled activation of morphogenesis to generate a functional human microvasculature in a synthetic matrix". Blood. 118 (3): 804–15. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-12-327338. PMC 3142913. PMID 21527523.

External links

- ATC codes: D03AX05 (WHO), M09AX01 (WHO), R01AX09 (WHO), S01KA01 (WHO)

- Hyaluronan at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)