Honan Chapel

The Honan Chapel (Irish: Séipéal Uí Eonáin,[4] formally Saint Finbarr's Collegiate Chapel, or The Honan Hostel Chapel[5]), is a small Catholic collegiate church built in the Celtic-Romanesque revival style on the grounds of University College Cork, Ireland. Designed in 1914, the building was completed in 1916 and fully furnished by 1917. Its architecture and fittings are representative of the Celtic revival movement which evoked the aesthetic style found in Ireland and Britain between the 7th and 12th centuries.[6]

| Honan Chapel | |

|---|---|

| Collegiate Chapel of St Finbarr[1] | |

Séipéal Uí Eonáin | |

West façade | |

| |

| 51.8935°N 8.4895°W | |

| Location | University College Cork, Cork |

| Country | Ireland |

| Denomination | Catholic Church |

| History | |

| Dedication | Fin Barre of Cork |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | James F. McMullen John O'Connell[2][3] |

| Architectural type | Romanesque Revival architecture |

| Style | Arts and Crafts movement Art Nouveau |

| Groundbreaking | 1915 |

| Completed | 1916 |

Its construction was initiated and supervised by a Dublin solicitor John O'Connell, a leading member of the Celtic revival and Arts and Crafts movements. He was funded by Isabella Honan (1861–1913), the last member of a wealthy Cork family, who provided large donations towards the build of the chapel. O'Connell oversaw both the architectural design and the commissioning of its exterior carvings and interior statuettes, floor, furniture and liturgical collection. He closely guided the architect James F. McMullen and the builders John Sisk and Sons, and hired the craftsmen and artists involved in its artwork, many of whom incorporated elements of the Art Nouveau style.

The Honan Chapel is internationally known[7] for its interior which is designed and fitted in a traditionally Irish style, but with an appreciation of contemporary trends in international art.[8] Its furnishings include the mosaic flooring, altar plates, metal work and enamels, liturgical textiles and sanctuary furnishings, and notably its nineteen stained glass windows; fifteen show Irish saints, the remainder show Jesus, Mary, St. Joseph and St. John. Eleven were designed and installed by Harry Clarke,Catherine O'Brien (artist)greatest work in stained glass".[9] A further eight were designed by A. E. Child, Catherine O'Brien and Ethel Rhind of An Túr Gloine ("The Glass Tower") cooperative studio, founded by Sarah Purser in 1903.

Background and construction

Population growth and migration in the early 20th century led to the development of a number of suburbs around Cork, including the building of churches to serve these new areas; the Honan Chapel was the first church to be built in Cork in the new century. Its development was rooted in a longstanding educational disagreement between the Protestant and Catholic hierarchies. Queens College Cork (today known as University College Cork, or UCC) was incorporated in 1845 as part of a nationwide series of new universities known as the Queen's Colleges,[11] under a charter that excluded Catholic students.[12] In 1911 the Queen's Colleges ceased as legal entities, and Catholics were thereafter eligible to attend. A few years previously, the Irish Universities Act of 1908 forbade government funding for any "church, chapel, or other place of religious worship or observance";[13] thus any centre for Catholic students would have to be built with private funding.[11]

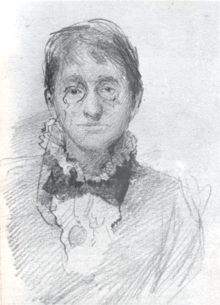

Isabella Honan (born Isabella Cunningham in 1861) was the sister-in-law of Robert Honan, the last male heir of a wealthy Catholic family of butter merchants.[14][15] Robert and his brother Matthew had both died by 1909,[16] and Robert had left his estate to Isabella. When she died in 1913[17] she left £40,000 to the city of Cork, including £10,000 which her executor, a Dublin solicitor John O'Connell, was instructed to use to establish a centre of worship for Catholic students in UCC, among other charitable and educational purposes.[18] These monies became known as the Honan Fund.[5][19] O'Connell used some of the money to fund scholarships for Catholic students at UCC,[20] and acquired the site of St Anthony's Hall (also known as Berkley Hall)[21] from the Franciscan order to develop an accommodation block for male Catholic students known as the Honan Hostel.[upper-alpha 1][2][22]

O'Connell was assisted in the chapel project by the University president, Sir Bertram Windle. The art historian Virginia Teehan[23] describes O'Connell and Windle as not only devout Catholics, but especially single-minded, creative, and energetic.[24]

The Honan Chapel was one of the first modern Irish churches conceived with a thematic design not directed by the clergy.[10] O'Connell, who became a priest in 1929 after the death of his wife,[25] was an active member of the Celtic revival movement, a member of the Irish Arts and Crafts Committee, a fellow of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, a member of the Royal Irish Academy, and was elected chairman of the Arts and Crafts Society of Ireland in 1917.[5][26][27] He was deeply interested in ecclesiastical archaeology,[20] and was acquainted with several members of the Irish Arts and Crafts and Celtic revival movements. O'Connell thus sought to construct a chapel that was "something more than merely sufficient ... a church designed and fashioned on the same lines and on the same plan as those which their forefathers had built for their priests and missioners all over Ireland nearly a thousand years ago."[28] He disliked the contemporary, international approach to church building – which he described as "machine made" – preferring a localised and uniquely Irish approach to style and form, which he sought from the most skilled local craftsmen available. He wanted work on the chapel to be "carried out in Cork, by Cork labour and with materials obtained from the City or County of Cork".[29]

O'Connell employed the firm of Cork architects James Finbarre McMullen and Associates[30] which had overseen the construction of the Eye, Ear & Throat hospital.[31] The building's plans were drawn up in 1914. The contractor John Sisk, also from Cork, was the principal builder[30] and completed the work at a cost of £8,000.[upper-alpha 2][32] The foundation stone, laid on 18 May 1915 by Thomas A. O'Callaghan D.D., Bishop of Cork,[33] records that the chapel was built "by the charity of Isabella Honan for the scholars and students of Munster".[32] It was consecrated on 5 November 1916, dedicated to Saint Finbarr, patron saint of Cork city and of the Diocese of Cork;[12][34] the grounds are close to a reputed early Christian monastic site founded by Finbarr.[35]

Architecture

O'Connell was mainly inspired by medieval architecture and the Honan Chapel's architectural style is Celtic-Romanesque.[18][28] Compared to the decorative and sculpted elements of the interior, its architecture is austere and modest, and has been described by architectural historian and conservationist Frank Keohane as "a little too commonplace and formulaic".[36][37]

The site is located on a hillside overlooking the valley of the River Lee.[28] The western entrance is approached by double-hinged wrought iron gates.[30] Its front was influenced by St. Cronan's Church, Roscrea and contains an arcade and gabled wall. Keohane describes its Antae as "surmounted by improbable pinnacles...and probably better regarded as clasping buttresses".[36]

The doorway contains moldings carved from lozenge and pellets,[36] and once contained an iron grille which has since been removed. It is capped by three limestone ribbed vaults,[38] supported by capitals carrying reliefs of the heads of six Munster saints: Finnbarr of Cork, Coleman of Cloyne; St. Gobnait of Ballyvourney; Brendan of Kerry, Declán of Ardmore and Íte of Killeedy.[39] Each figure is further represented in the stained glass windows. The reliefs were sculpted by Henry Emery, assisted by students at the nearby Cork School of Art.[39] The tympanum over the door was designed by the sculptor Oliver Sheppard, and is dominated by the figure of St. Finbarr, dressed in bishop's vestments.[36][38] The timber doors hang on wrought-iron strap-work hinges designed by the architect William Scott in (according to the writer Paul Larmour) a "Celticized art nouveau" style.[39]

The chapel's small interior has a very simple layout:[33] a main entrance, six-bay nave, two-bay square chancel and a nunnery.[30] It does not contain either aisles or transepts.[40] The oblong nave is 72 by 28 feet (22 by 8.5 m), and contained within a timber barrel vaulted ceiling that ends at a square ended area around the chancel 26 by 18 feet (7.9 by 5.5 m). The sacristy is on the north side (left, looking towards the altar) under the bell tower.[33]

The nave is relatively plain,[28][30] and lacks shrines where persons could light candles or place flowers near devotional images; in this way, it is similar to a Protestant church.[41] Its plan and round campanile are inspired by 9th-century round towers.[30]

The building is listed as a protected structure under Section 51 of the Irish Planning and Development Act.[42]

Mosaic floor

The mosaic flooring was designed and installed by the UK-based mosaic artist Ludwig Oppenheimer.[43] It is decorated with symbols of the zodiac,[42] images based on the mythological "River of Life",[30][44] and depictions of flora, fauna and river scenes.[19] These designs celebrate the Genesis creation narrative, and illustrate passages from the Old Testament including the "Benedicite" (also known as "A Song of Creation") from the Book of Daniel, which was sung during the office of lauds on Sundays and feast days. The pattern at the entrance contains a verse from Psalm 148 ("Praise to the Lord from Creation").[45]

The floor consists of four sections. The main entrance on the west side is dominated by a sunburst and stars surrounded by signs of the zodiac, while the imagery on the aisle depicts the head of a beast whose jaws open as the mouth of a river[46] from which fish swim toward the chancel. The east side of the nave shows a large coiled sea creature which is part serpent, part dragon, and part whale.[37] There are stags, deer, sheep and other animals drinking from a river and surrounded by exotic birds flying in a forest.[37] The section inside the chancel show a globe and symbols of creation, including animals, plants and planets.[47] The four sections are unified by interlaced Celtic and zoomorphic border designs.[48]

The representations of the sun and surrounding night stars at the entrance signify both the new day and the resurrection, as Jesus is traditionally believed to have risen at dawn. Reflecting 12th-century Christian art, the presence of signs of the zodiac symbolise God's dominion over time.[49] The beast's head in the aisle contains a series of tripartite motifs representing the Trinity: spirals, trefoil knots and interlace containing three saltire crosses. The sea creature at the east end of the nave is mentioned in the verse on the floor by the entrance dracones et omnes abyssi ("Dragons and all the depths");[50] alongside are the words cete et omnia quae moventur in aquis ("whales and all that move in the water"), which in medieval exegesis conjured images of death and reference the Biblical story of Jonah.[49]

The colouring of the floor by and inside the chancel is more subdued and the imagery more restrained. The images show a paradise which can be interpreted both as the garden of Eden and the eternal paradise promised at the end of time. The imagery is of the seasons, the classical elements, and symbols of the resurrection.[51]

A similar depiction on a 5th-century sarcophagus in the Lateran Museum shows Jonah swimming towards the open jaws of a whale with horned ears, and a long, coiled tail.[49][52] In both examples, the reference serves to emphasise how Jesus overcame death. This connection is further made by the inclusion of the trees (the tree of life) which in mythology grow in paradise and represent Christ, and the surrounding animals at rest, presented as symbols of his Christian followers.[53]

Altar

The chapel has had two altars; the original was a plain slab of Irish limestone selected to contrast with the ornately carved Italian marble then in fashion which O'Connell disliked.[29] It contained silver fittings by Edmond Johnson, Dublin and William Egan and Sons of St Patrick's Street, Cork.[54] The altar was positioned on a five-legged table, each leg lined with an Irish crucifix[55] formed from simple geometric designs including zig-zag patterns in lozenge and saltire, continuous dots, and chevrons.[56][57]

The chapel's original design contravened the requirements of the Second Vatican Council in several ways:[58] it was based on medieval churches and the old rites; it was built with a large spatial divide between the nave and chancel; and the altar was positioned at the very back of the chancel with the priest facing away from the congregation.[59] In 1986, in response to these changed liturgical requirements, the chapel authorities commissioned the architect Richard Hurley to redesign elements of its fixtures.[60] He in turn employed the German-Irish sculptor Imogen Stuart to undertake a redevelopment, including replacement of the altar, pulpit, the ceremonial chairs and the baptismal font.[16]

Stuart's replacement altar was constructed in oak, and depicts two of the Evangelists.[58] Being movable it allowed clergy and attendants to be closer to the congregation.[59] Although first intended for the centre of the chancel at the focal point of the mosaic floor, this proved to be too far back and was impractical during ceremonies.[61] Although Stuart works with other materials, she favours wooden carvings, as exemplified by those at the front of the Honan altar.[62]

Tabernacle

The tabernacle is positioned at the far end of the chancel and is the chapel's focal point. It is formed from carved stone and shaped in a manner reminiscent of the arched roofs and entrances of medieval Irish churches.[63] Its upper, triangular, panel is set in the gable of the "entrance", and shows the Trinity of God the father, the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove, and Jesus crucified; around them, two angels carry the sun, moon, and other symbols of creation.[64]

The lower, rectangular, panel represents the doorway and is set against a background of branches and leaves attached in silver-gilt; it shows the Adoration of the Lamb, with the lamb standing on a brightly coloured altar decorated with three ringed crosses, and two angels acting as servers kneeling before it.[16][64] The dove is surrounded by what Teehan describes as "the deep blue void of Heaven".[64] Here he is accompanied by flights of angels, carrying instruments of the Passion.[16] These enamel embellishments were by the Irish craftsman and stained glass specialist Oswald Reeves,[65] and have been described as the best of his work.[64]

Stained glass windows

.jpg)

Since Ireland had no extant medieval glass tradition to emulate, O'Connell initially planned that Sarah Purser's studio, An Túr Gloine, would produce all of the windows for the chapel, Purser's studio being at that time the art's leading proponent. However he was impressed by Clarke's early designs, and set Clarke studio and An Túr Gloine in competition for the commission.[66] [67] After seeing Clarke's designs for the St. Gobnait window, the contract was awarded jointly with the greater number of windows being assigned to Clarke.[68] After the chapel's opening, the collector Thomas Bodkin wrote that "nothing like Mr Clarke's windows had been seen before in Ireland" and praised their "sustained magnificence of colour ... intricate drawing [and] lavish and mysterious symbolism."[69]

The chapel contains nineteen windows: six on each side of the nave, four in the chancel, and three in the west gable.[70] Of these, eleven were designed by Harry Clarke, and eight by An Túr Gloine. Of the latter, four are by A. E. Child, three by Catherine O'Brien, and one by Ethel Rhind.[58] Although the windows from each studio contain similar imagery, their styles differ greatly.[70] Clarke's are highly detailed while An Túr Gloine's are deliberately simple. Both studios were asked to depict Gaelic saints from the early-medieval, so called "golden age", of Christianity in Ireland.[71] Each displayed their cartoons in Dublin before they were physically realised in Cork; both shows were highly praised, and critics debated which group was superior.[72]

The windows in the chancel are: Our Lord (or "Christ in Majesty") (Child), Our Lady of Sorrows (Clarke), St. John (O'Brien) and St. Joseph (Clarke).[73] To the right of the chancel looking down are: St. Finnbar (Clarke), St. Albert (Clarke), St. Declan (Clarke), St. Ailbe (Child), St. Fauchtna (Child) and St. Munchin (O'Brien). To the left are: St. Ita (Clarke), St. Coleman (Child), St. Brendan (Clarke), St. Gobnait (Clarke), St. Flannan (O'Brien) and St. Carthage (Rhind). The windows in the west gable are all by Clarke and represent St. Patrick, St. Brigid and St. Columcille.[58][74]

Some of Clarke's windows were endangered by nearby fighting during the 1916 Easter Rising in Dublin,[75] and the designs and illustrations for several of his other works were destroyed.[76]

Harry Clarke

Clarke offered five designs for the Honan project, including a cartoon for the St, Gobnait window.[77] He was then in his early twenties and his Honan windows – his first in a public space – established his reputation as a significant international artist.[upper-alpha 3][68][78] A contemporary reviewer, comparing the windows to French medieval glass, including those in the Gothic royal chapel of Sainte-Chapelle, described them as "remarkable" and a "distinct advance on anything which has been heretofore done in Ireland in stained glass.[41] In particular, his blending of bold and dark colours has been praised, especially in the effects they achieve in morning light.[79] The designer Percy Oswald Reeves highlighted the windows for their "beauty of ... colour, quality and treatment of each piece of glass."[80] His merging of Catholic and early medieval imagery in a modern and individualised style was at odds with prevailing trends in Irish church art.[81][82] According to scholar Luke Gibbons, Clarke's break "from episcopal interference ... enabled [him] to exploit vernacular traditions of local saints ... that belonged more to legend and folklore ... and whose popular appeal lay outside the highly centralised power of post-famine ultramontane Catholicism."[78]

Clarke's windows are all single light, each consisting of nine separate panels, with rich colouring and a deep, thick royal blue throughout. They contain simplified, often whimsical forms which are nevertheless highly stylised. The writer M. J. O'Kelly suggests they evoke, "the spirit of the ancient Celt".[63] His designs blend Catholic iconography with motifs from Celtic mythology[75] in a style that draws heavily from Art Nouveau, in particular the darker, fin de siècle works of Gustav Klimt, Aubrey Beardsley and Egon Schiele.[78]

The Brendan, Gobnait and Declan windows were completed as a group in the late summer and autumn of 1916. Following the 1916 Easter Rising, Clarke and his wife left Dublin to move into a cottage in Mount Merrion, Blackrock. Clarke was under considerable pressure to complete and install the three windows in time for the chapel's November 5 consecration.[83]

Brigid, Patrick and Columcille

Designed in 1915, the Brigid, Patrick and Columcille windows were the first of Clarke's designs to be completed. The three-light windows are located on the west wall above the main entrance door[84] with a base of five lilies under Patrick's light. The deep blue and green hues in Patrick's window were achieved using sheets of "antique" pot metal glass which were made on special order by Chance's in Birmingham.[85]

Brigid is depicted alongside a calf, Patrick with a shamrock in his right hand, and Columcille alongside two flying doves. The Brigid light is especially but moved for a time detailed and contains an angel at the top of the window and another four hovering at its foot. The writer Lucy Costigan suggests that the lilies may represent Brigid's miracles, prophesies, prayers and charities.[86]

Gobnait

The windows contain Celtic designs and motifs, as well as figures and incidents from the life of each saint. The most obvious Celtic embellishments are Mary's red hair and green halo, and Brendan's pampooties.[78] A number of the early Honan windows were completed by assistants working from his designs, but the Gobnait window, on the north side of the chapel, was fully executed by him and is widely considered the high point of his career.[87] Gobnait was a healer who established a convent in Ballyvourney and became the patron saint of bees.[upper-alpha 4] She is shown in half-profile with a pale, thin and ascetic face and individualistic, unmistakably Irish features. She wears royal blue and purple robes adorned with lozenged jewels, a veil and a silver cloak.[70][87] The window's borders are lined with beaded decorations in ruby and blue.[17] Her clothing draws from Léon Bakst's costume for Ida Rubinstein's 1911 performance of "Le Martyre de saint Sébastien".[88] Her right arm is outstretched in a pose that draws from both Beardsley and Alesso Baldovinetti's c. 1465 Portrait of a Lady in Yellow. Clarke and his assistant Kathleen Quigly completed the study under time pressure over five weeks in 1914, during the offer period for the commission.[77]

The window was described by Teehan as "kaleidoscopically sumptuous" and "filled with a wealth of art historical allusions, often unexpected".[88] According to the Irish novelist E. Œ. Somerville, it conjures late 19th century decadence in its resemblance to an Aubrey Beardsley–type female face, which "though horrible [is] so modern and conventionally unconventional ... [Clarke's] windows have a kind of hellish splendour."[89]

Brendan

.jpg)

The St. Brendan window references a number of incidents from the "Voyage of Saint Brendan the Abbot", first recorded c. 900 AD. Brendan wears a robe of blue, purple, greens and gold hues, and (reflecting his reputation as a seaman and voyager) he holds a paddle in his left hand.[90] In the lower panel a grotesque, claw-limbed Judas Iscariot,[41] appears as a "devilish figure surrounded by red and yellow flames";[90] Brendan is said to have found Judas abandoned on a rock in the ocean, to be tormented for eternity by demons. In another chapter, he arrives at an island, the "Paradise of Birds", where birds sing psalms "as if with one voice"[71] in praise of God; Clarke depicts this in the sketches of birds on the window's borders.[71]

Declan

.jpg)

Declán of Ardmore was patron saint of the Decii clan of County Waterford. The upper panel of his window depicts his return from Wales, carrying the bell sent to him as a gift from Heaven.[91]

The lower panel shows Declan meeting St. Patrick on the road from Rome.[92]

Albert of Cashel

Albert of Cashel wears a purple chasuble, crimson stole and a bishop's mitre. His window contains several Celtic motifs, including bronze spirals around his hair and beard.[93] Depictions of Albert sometimes detail magical feats associated with him, which Gibbon describes in Clarke's work as "daring" for a church window, given such deeds owe more to pagan legend rather than "respectable traits of virtue and holiness."[78]

Our Lady and St. Joseph

Clarke's two chancel windows, of Our Lady and St. Joseph, were installed in 1917, a year after the chapel was opened.[94]

Clarke, St Finbarr, central panel

Clarke, St Finbarr, central panel Clarke, St Finbarr, lower register

Clarke, St Finbarr, lower register Clarke, St. Albert, detail

Clarke, St. Albert, detail Clarke, St. Ita, lower register

Clarke, St. Ita, lower register

An Túr Gloine

.jpg)

Sarah Purser and Edward Martyn formed the workshop An Túr Gloine ("The Glass Tower")[9] in 1902 to advance the artistic quality stained-glass production in Ireland.[36] It consisted of pupil's of A. E. Child, who was then teaching at the Metropolitan School of Art in Dublin, who she employed to managed the workshop.[95][96] Their cartoons were, like those from Clarke's studio, designed and built in Dublin before installation in Cork. Their eight windows are attributed to Child (St. Ailbe, St. Fachtna and St. Coleman), and his then pupils Catherine O'Brien (St. John, St. Flannan and St. Munchin) and Ethel Rhind (St. Carthagh).[63]

.jpg)

Although their subject matter is similar to Clarke's, they are very different in style and not of the same quality, being somewhat conventional by comparison.[58] They are minimalist in line and colour, consisting of a dominating but simply rendered and naturalistic central figure in pale hues,[70] surrounded by uncomplicated, largely empty opaque sub-panels. The most prominently placed window is Child's "Our Lord" on the east gable above the altar.[70] Child depicts the risen Christ in simple forms and subdued colours, and with a strong but dignified facial expression. O'Kelly's describes the portrait of Christ's eyes "as look[ing] out on humanity with a welcoming and understanding sympathy."[97]

St. John

O'Brien's "St. John" window in the only in the chapel to portray a biblical narrative,[98] and is usually considered the strongest of An Túr Gloine's windows. It is divided into three registers, each containing pairs of medallions. Its imagery mostly concerns the life of Christ as told in the Gospel of John, and draws more from close readings of scripture than traditions of iconography. The upper register is based on Revelations 1:1, and shows a vision of the glorified Christ in Majesty, with the Alpha and Omega symbols and the seven candles. More characteristic of Protestant than Catholic iconography[upper-alpha 5] is the depiction of a serpent with its mouth open, coiled around the cross below Jesus' feet.[99]

.jpg) "St. Ailbe" (detail), Child, c. 1916

"St. Ailbe" (detail), Child, c. 1916.jpg) "St. Flannan" (detail), O'Brien, c. 1916

"St. Flannan" (detail), O'Brien, c. 1916

Furnishings, textiles and other objects

O'Connell commissioned Egan & Sons for the altar plate and vestments. He had a strong view on how the chapel should be presented and was keen that its artwork would draw from Ireland's ancient culture. In this, he was heavily influenced by 19th century antiquarian research into early Christian and early medieval traditions and art, in particular the early medieval metal and stone works, and illuminated manuscripts at the time being rediscovered. He wanted the Honan Chapel to further reflect and promote the earlier period's emergent influence on Irish literature and visual culture.[29]

The chapel contains relatively few furnishings; O'Connell did not want excessive ornamentation, and instead, become what Teehan describes as a "peaceful, dignified space."[100] The furnishings and pews were designed to blend into the chapel's Celtic Revival style and (according to Teehan) create "a way that represented the spirit and skill of earlier times [that] could be nonetheless be fully appreciated by contemporary society. The overall effect is one of simplicity and restfulness."[100] Such pieces include the circular iron ventilation ceiling panels and the oak chair and kneeler reserved for the president. Most of these fittings were designed by McMullen, most of the remainder, including the 28-long and 3-short oak pews,[101] by Sisk & Son. Changes in liturgy following Vatican II meant that a number of furnishings had to be replaced,[100] a project overseen by the chapel's then dean, Gearóid Ó Súilleabháin.[62]

The chapel has an extensive collection of metalwork and enamel pieces built by Edmond Johnson's and Egan & Sons, all in the Celtic Revival style. A highlight is the large processional cross, a replica of the 12th-century Cross of Cong,[36] which contains a number of inscriptions, including a remembrance for the chapel's benefactors Mathew, Robert and Isabella Honan; and for John and Mary O'Connell.[16][102] Other items include further processional crosses, chalices, candlesticks, dishes, bells, hinges, and the iron gates at the entrance.[103]

Most of the textile collection was designed by the Durn Emer guild, Dublin, and includes vestments, chasubles, burses, veils, stoles, maniples, altar cloths, wall hangings and altar fronts. The tapestry dossal on the east wall was designed and woven by Evelyn Gleeson, and contains Celtic symbols borrowed from the Book of Durrow.[104] Materials vary from silk embroidery, gold braid, gold thread, linen, poplin and cotton. The names of seamstresses from the Egan workshop are embroidered in the lining of some of the textile commissions.[23] In general the textiles are coloured in line with changes in the seasons of the liturgical year. Most of the designs are centred around the Life of Mary, or the Passion, or Crucifixion, with black and white being the predominant colours.[105]

Michael Barry Egan's firm designed and sew many of the vestments.[106] A highlight is the Y-shaped, silver threaded chasuble in black poplin cloth, used as a vestment for funerals. A violet altar cloth with a frontlet, decorated with Celtic interlacing in shades of purple silk, orange and yellow highlights, and a border of lemon and violet cotton satin, is used to decorate the altar and candlesticks.[107] The "Black set" of Honan textiles includes an altar frontal with a Celtic cross based on a grave stone from Tullylease Church in Cork, a black cope and hood containing a crown of thorns design and a black chasuble designed for funeral masses containing Celtic interlace patterns.[105]

The pipe organ is on the west wall in a timber frame.[30] It was built by Wicklow native Kenneth Jones and installed in 1996.[16][42]

Administration and liturgical services

The chapel's day-to-day operations are run in conjunction with UCC's chaplaincy department, while management and funding is provided by the Honan Trust, established in 1915.[108] The Honan is a separate legal identity to the university, and owns its own land, which is bounded by the chapel gates.[109] Its dean is secretary to the Board of Governors of the trust, and manages the staff and finances, and is responsible for the chapel's conservation and maintenance.[110]

The Honan holds daily and Sunday masses, as well as memorial services for deceased students and staff.[111] Morning prayers are held each Monday, and daily during Advent and Lent.[111] It hosts an average of 150 wedding services per year for graduates, which is a funding source for the chapel.[112][113] It also host a number of musical and other cultural events.[114]

Footnotes

- The chapel remains standing, but the nearby Honan Hostel (opened 1914) was demolished and replaced by the O'Rahilly Humanities Building in 1998. See UCC Conservation plan

- In 1996, Sisk's company were contractors on the O'Rahilly Building project - a complex built on the site of the former Honan Hostel that stood between 1914 and 1991. See UCC website

- Clarke's career in stained-glass peaked early; from the mid 1920s he was preoccupied with legacy commissions left over from his father's workshop. See Gordon Bowe (1985), p. 36

- Gobnait was born in County Clare but lived for a time on Inisheer, where she founded a church. Clarke often visited the island during in the 1900s and later honeymooned there. According to the art historian Patricia Rogers, he "certainly would have seen the famous ruins of Gobnet's first church on Inisheer, and these may have attracted him to the subject of this saint." See Rogers (1997), p. 209

- O'Brien, who joined An Túr Gloine in 1904, came from an Anglo-Irish and devout Church of Ireland family and is credited with three of the chapel's windows. See Hayes & Rogers (2012), pp. 130, 131

References

Citations

- "Honan Chapel History". honanchapel.com. Archived from the original on 22 November 2018.

- Leland 2004.

- Larmour 1992.

- "Honan Chapel - Séipéal Uí Eonáin". UCC. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- Wilson 2013, p. 24.

- Sheehy 1980, pp. 163, 164.

- Teehan 2016, p. 80.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 3.

- Gordon Bowe 1985, p. 39.

- Keohane 2020, p. 209.

- O'Callaghan 2016, p. 163.

- Baker 1999, p. 165.

- "Irish Universities Act, 1908". irishstatutebook.ie. Government of Ireland. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- O'Connell 1916, p. 11.

- Ryan 2016, p. 3.

- O'Callaghan 2016, p. 168.

- Rogers 1997, p. 209.

- O'Callaghan 2016, p. 164.

- Leyland, Mary (25 January 2010). "An Irishwoman's Diary". Irish Times. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Good 2016.

- 90th anniversary of the dedication of the Honan Chapel, Cork (PDF) (Report). University College Cork. 5 November 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2017.

- Fennessy 2014, p. 282.

- "Forgotten Faces of Art: The women of the Honan Chapel". University College Cork. 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 31.

- Keogh & Keogh 2010, pp. 111–139.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 29-30.

- Gordon Bowe 1985, pp. 29–40.

- J.J.H. 1916, p. 613.

- Wilson 2018, p. 21.

- NIAH 2000.

- "McMullen, James Finbarre". Dictionary of Irish Architects. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- O'Callaghan 2016, p. 165.

- O'Kelly 1950, p. 291.

- MacErlean 1909.

- Wilson 2013, p. 25.

- Keohane 2020, p. 210.

- O'Kelly 1950, p. 293.

- O'Kelly 1950, p. 292.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 40.

- O'Connell 1916, p. 36.

- Wilson 2018, p. 25.

- McClatchie 2006, p. 14.

- "Oppenheimer, Ludwig, Ltd". Dictionary of Irish Architects. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- Field 2006.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 114.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 107.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, pp. 111, 112.

- O'Kelly 1950, pp. 293, 294.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 117.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 116.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, pp. 120–121.

- Lawrence 1962, pp. 289–296.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 118.

- Wincott Heckett 2000, p. 167.

- O'Kelly 1950, p. 294–295.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, pp. 55, 56.

- Wilson 2013, p. 27.

- Keohane 2020, p. 211.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 196.

- Stuart 2016.

- "Portfolio: Honan Chapel, University College Cork". Richard Hurley & Associates Architects. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- "The Big Story: Imogen is carving a life of her own". Irish Independent. 28 August 2014. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- O'Kelly 1950, p. 295.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 86.

- Larmour 1992, p. 186.

- Kennedy 2015, p. 99.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, pp. 166-167.

- Gordon Bowe 1979, p. 99.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 163.

- O'Kelly 1950, p. 294.

- Wilson 2018, p. 28.

- O'Kelly 1950, p. 294-295.

- Hayes & Rogers 2012, pp. 128, 130.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, pp. 102, 167.

- Wilson 2018, p. 19.

- Costigan & Cullen 2010, p. 20.

- Rogers 1997, p. 207.

- Gibbons 2018, p. 332.

- Costigan & Cullen 2010, p. 97.

- Gordon Bowe 1985, p. 36.

- J.J.H. 1916, p. 612.

- Wilson 2018, p. 29.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 174.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 168.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, pp. 169, 173.

- Costigan & Cullen 2019, pp. 77–78.

- Costigan, Lucy. "St. Gobnait". harryclarke.net. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 181.

- Costigan 2019.

- Costigan, Lucy (27 March 2020). "St. Brendan". harryclarke.net.

- O'Connell 1916, p. 45.

- O'Connell 1916, p. 46.

- Costigan & Cullen 2019, p. 57.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 169.

- Gibbons 2018, p. 311.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, pp. 99, 167.

- O'Kelly 1950, p. 294-5.

- Hayes & Rogers 2012, p. 128.

- Hayes & Rogers 2012, p. 129.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 232.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 233.

- Beecher 1971, p. 53.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, pp. 202–209.

- O'Connell 1916, p. 56.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, pp. 210–225.

- O'Connell 1916, p. 57.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, pp. 201.

- Peer Review Group 2008, p. 16.

- Teehan & Heckett 2005, p. 21.

- Peer Review Group 2008, pp. 14, 15.

- Peer Review Group 2008, p. 11.

- Peer Review Group 2008, pp. 14, 16.

- "Marriage at the Honan Chapel, Cork". Diocese of Cork and Ross. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Peer Review Group 2008, p. 14.

Sources

- Baker, R. A. (1999). "Rev. William Hincks (1794-1871) and the Early Development of Natural History at Queen's College (University College), Cork". The Irish Naturalists' Journal. Irish Naturalists' Journal. 26 (5/6). JSTOR 25536241.

- Beecher, Seán (1971). The Story of Cork. Cork: Mercier Press. ISBN 978-1-4000-3490-1.

- Costigan, Lucy; Cullen, Michael (2019). Dark Beauty: Hidden Detail in Harry Clarke’s Stained Glass. Dublin: Irish Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-7853-7233-9.

- Costigan, Lucy; Cullen, Michael (2010). Strangest Genius: The Stained Glass of Harry Clarke. Dublin: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-8458-8971-5.

- Fennessy, Ignatius (2014). "Some Papers Concerning Brother Jarlath Prendergast, OFM, and also St Anthony's Hostel, Cork". Collectanea Hibernica. 46/47. JSTOR 30004738.

- Field, Robert (2006). "L. Oppenheimer Ltd And The Mosaics Of Eric Newton" (PDF). Tiles and Architectural Ceramics Society. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- Gibbons, Luke (2018). "Afterword: 'Cloistral Silverveined', Harry Clarke and the Intensely Modern". In Griffith, Angela; Kennedy, Róisín; Helmers, Marguerite (eds.). Harry Clarke and Artistic Visions of the New Irish State. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-7885-5045-1.

- Good, Wendy (3 November 2016). "UCC's Honan Chapel celebrates centenary". Cork Independent.

- Gordon Bowe, Nicola (1985). "The Arts and Crafts Society of Ireland (1894-1925) with particular reference to Harry Clarke". The Journal of the Decorative Arts Society 1850 - the Present. 9. JSTOR 41809143.

- Gordon Bowe, Nicola (1979). A Monograph and Catalogue Published to Coincide with the Exhibition "Harry Clarke", 12 November to 8 December 1979 at the Douglas Hyde Gallery". Douglas Hyde Gallery, Trinity College.

- Keogh, Ann; Keogh, Dermot (2010). Bertram Windle: The Honan Bequest and the Modernisation of University College Cork, 1904-1919. Cork: Cork University Press. ISBN 978-1-8591-8473-8.

- Keohane, Frank (2020). Cork: City and County. Buildings of Ireland. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-22487-0.

- Hayes, Myra; Rogers, Jessie (2012). "Lost in Translation". Irish Arts Review. 29 (4). JSTOR 41763156.

- J.J.H. (1916). "Reviewed Work: The Honan Hostel Chapel, Cork. Some Notes on the Building and the Ideals which inspired it by John R. O'Connell". Studies: An Irish Quarterly Review. Franciscan Province of Ireland. 5 (20). JSTOR 25701079.

- Kennedy, Róisín (2015). "The Revival and Visual Art – Harry Clarke's Geneva Window" (PDF). University College Dublin. Retrieved 10 August 2019.

- Larmour, Paul (1992). The Arts and Crafts Movement in Ireland. Belfast: Friar's Bush Press. ISBN 978-0-9468-7253-4.

- Lawrence, Marion (1962). "Ships, Monsters and Jonah". American Journal of Archaeology. 66 (3). JSTOR 501457.

- Leland, Mary (2004). "Relics of a resurgent Ireland". Irish Times. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- McClatchie, Katherine, ed. (2006). Guide to Protected Structures in Cork City (PDF) (Report). Cork City Council.

- MacErlean, Andrew (1909). "St. Finbar". Vol. 6. New York: The Catholic Encyclopedia. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - NIAH (2000). "Honan Chapel, Donovan Road, Cork, Cork City". buildingsofireland.ie. National Inventory of Architectural Heritage. Retrieved 22 November 2018.

- O'Callaghan, Antóin (2016). The Churches of Cork City. Dublin: The History Press Ireland. ISBN 978-1-845-88893-0.

- O'Connell, John (1916). The Honan Hostel Chapel Cork: Some Notes on the Building and the Ideas which Inspired It. Cork: Guy & Company.

- O'Kelly, Micheal J. (1950). "The Honan Chapel". The Furrow. 1 (6). JSTOR 27655609.

- Peer Review Group (2008). "Peer Review Group Report: Chaplaincy" (PDF). University College Cork. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Rogers, Patricia (1997). "Bees and Butterflies: Two Drawings by Harry Clarke". Journal of Glass Studies. 39. JSTOR 24190174.

- Ryan, Niamh (2016). "Made in Cork, The Arts & Crafts Movement 1880s-1920s," (PDF). Crawford Art Gallery. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- Sheehy, Jeanne (1980). The Rediscovery of Ireland's Past: Celtic Revival, 1830-1930. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-5000-1221-5.

- Stuart, Imogen (2016). "Signature pieces in Honan Chapel". Irish Times. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Teehan, Virginia (2016). "Celtic renaissance". Irish Arts Review. 33 (1). JSTOR 24891719.

- Teehan, Virginia; Heckett, Elizabeth (2005). The Honan Chapel: A Golden Vision. Cork: Cork University Press. ISBN 978-1-8591-8346-5.

- Wilson, Ann (2018). "Early Twentieth Century Irish Catholic Devotional Imagery: The Honan Chapel Windows". In Griffith, Angela; Kennedy, Róisín; Helmers, Marguerite (eds.). Harry Clarke and Artistic Visions of the New Irish State. Irish Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-7885-5045-1.

- Wilson, Ann (2013). "Arts and Crafts and Revivalism in Catholic Church Decoration: A Brief Duration". Éire-Ireland. 48 (3/4).

- Wincott Heckett, Elizabeth (2000). "Heavens' Embroidered Cloths: Textiles from the Honan Chapel, University College Cork". Textile Society of America.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Honan Chapel. |

- "Honan Collection Online". Archived from the original on 29 January 2019.

- Notre Dame Folk Choir performing in the Honan, 2016