Hòa Hảo

Đạo Hòa Hảo (Vietnamese: [ɗâːwˀ hwàː hâːw] (![]()

In Hòa Hảo homes, a plain brown cloth serves as an altar, at which the family prays morning and night. Separate altars are used to honor ancestors and the sacred directions. Only fresh water, flowers, and incense are used in worship; no bells or gongs accompany prayers. A believer away from home at prayer times faces west (i.e., toward India) to pray to the Buddha. Adherents are expected to attend communal services on the 1st and 15th of each lunar month and on other Buddhist holy days.

History

Huỳnh Phú Sổ faced a great deal of trouble when he began to spread the ideas of his religion, a large part of which was Vietnamese nationalism, a dangerous idea in that time of French colonial rule. He was put in an asylum because of his preaching, but supposedly converted his doctor to the Hòa Hảo belief. As the popularity of Hòa Hảo grew, Huỳnh Phú Sổ made a series of prophecies about the political future of Vietnam. He said that the "true king" would return to lead Vietnam to freedom and prosperity, which caused most Hòa Hảo to support the Nguyễn pretender: Marquis Cường Để, living abroad in Japan.

During World War II, the Hòa Hảo supported the Japanese occupation and planned for Cường Để to become Emperor of Vietnam. However, this never happened and the Hòa Hảo came into conflict with the communists both because the Việt Minh were anti-Japanese and because of their Marxist opposition to all religion. During the State of Vietnam (1949–1955), they made arrangements with the Head of State Bảo Đại, much like those made by the Cao Đài religion and the Bình Xuyên gang, which were in control of their own affairs in return for their nominal support of the Bảo Đại regime. In fact, the control of this government by France meant that most Hòa Hảo opposed it.

During the early years of the Vietnam War in the 1960s, An Giang Province and its capital Long Xuyên were among the few places in the Mekong Delta where Viet Cong activity was minimal and American and South Vietnamese troops could move without fear of sniper attack. After the war, the Hòa Hảo were allowed to remain, but like all religions, under strict Communist control.

Buu Son Ky Huong religion

The Đạo Bửu Sơn Kỳ Hương religion was described by its adherents as "committed to the world". The basis of the Buu Son Ky Huong religion was the Buddha Master's claim to be a messenger from Heaven who had come into the world to warn mankind of the imminence of apocalypse. The key to this cult was simplicity, flexibility, and frugality. No one could plead lack of means or difficult circumstances as a justification for not carrying out his own religious duties and for relying instead on monks, but these duties were kept to a minimum. The Buddha Master's advocacy of ritual frugality probably attracted many poor peasants by allowing them to turn practical necessity into religious virtue. Because of the overwhelmingly domestic nature of the cult, the French observer Georges Coulet called it in 1926 the " Third Buddhist Order, " explaining that it was neither monastic nor congregational but mostly lay. However, he observed, there were days when adepts were expected to gather in pagodas that belonged to the sect: " This cult is sensibly a Buddhist cult. It consists of the observance of fasts and abstinences, of the daily recitation of prayers, of invocations which must be said at certain hours of the day or night: it imposes visits to mountain pagodas on the fifteenth day of the first, seventh, and tenth months of the Annamite year. Fasts and abstinences can be once a month, once every two months, once a week, once every two weeks, or perpetual . . . Offices are celebrated thrice a day: at dawn, noon, and dusk. At these times, candles are lit on the altar, and joss-sticks are placed in the incense-burner; the caretaker of the temple gives several strokes of the bell and the faithful perform several prostrations in front of the altar, bowing their heads to the ground. Prayers are said in low voice; a few beads are recited. Finally, in exchange for a contribution in money or goods, amulets are distributed by a monk of the pagoda; these amulets preserve from death, illness, and misfortune.[2]

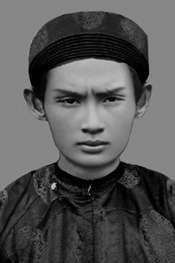

Huynh Phu So

Background

The founder of the Hoa Hao was Huynh Phu So, who took for the name of his sect the village of Hoa Hao, in the Thot Not District of what is now An Giang Province. So's background is not completely known; but most authorities agree that he was a mystic who saw a vision instructing him to launch a new religion. He organised his sect in 1930, declared himself a prophet, and began to preach a doctrine based on simplicity and faith. Within a year, he had gathered a following of over 100,000 converts; and through his preaching, he established contact with another two million people in the Mien Tay region.[3]

Beliefs

Huynh Phu So taught that each member of the sect could achieve direct communion with the Lord Buddha, and that internal faith was more important than external ceremony. Moreover, the care of the living has priority over the welfare of the dead. Huynh Phu So restated that the doctrine was lay-oriented, and he advocated the reduction of cultic expenses not only in the practice of Buddhism but also on all ceremonial occasions. He attacked the custom of overspending at the New Year, of bankrupting one's family at funerals and weddings, and of trying to outdo one's neighbors in conspicuous consumption. It was wrong to conceive of religious piety as something separate from the rest of life, as a set of exercises that were to be performed on an occasional basis. Huynh Phu So's stated objective was to "combine the ideal of universal love and charity with a new method of organizing society in order to serve better our people and mankind.” But he had no real understanding of the workings of a complex social system and therefore could not evolve a strategy for bringing about the new order of things, except through the violent expansion of his sect. Huynh Phu So embroidered the idea that money is the source of evil, both for those who had not enough and for those who had too much.[2]

While Huynh Phu So is regarded by most commentators as a traditionalist, and indeed many of his teachings support such an interpretation, he also had a well-defined modernizing vision, evident, for example in his imprecation against superstition.[4]

Influence

No Vietnamese leader of the time possessed personal charisma to quite the same degree as Huynh Phu So. A measure of Huynh Phu So's powers of persuasion is that he made his mark as a healer despite his own well-publicised ill-health. Throughout his career, healing remained an important feature of his work; a substantial number of pamphlets describing the herbal remedies employed by Huynh Phu So still exist. So divided diseases into two categories: those that were the result of ordinary ill-fortune, and those that were the result of karmic retribution. The latter was not amenable to treatment; only repentance could alleviate it. Each of these new recruits were people of little education, interested in action rather than in doctrinal or political questions. They put themselves entirely at the service of Huynh Phu So. By August 1940, the Can Tho authorities were alarmed by their activities and by the destabilizing influence of Huynh Phu So. He was summoned for a psychiatric examination at Can Tho hospital. Huynh Phu So was taken to Cho Quan hospital in Cho Lon and put under the care of a Vietnamese doctor named Nguyen van Tam. The latter's verdict was more charitable: "This monk has never presented signs of agitation or insanity. He is mentally weak, with a disharmony of the intellectual faculties." In spite of being considered "mentally weak," So converted several of the hospital wardens and, more important, his own doctor. For a man who had never had any qualms about being called the Mad Monk, this was a resounding triumph which the sect exploited to the full. The doctor became a devoted follower of Huynh Phu So, until he was assassinated by the Viet Minh in 1948. In May 1945 Huynh Phu So issued a pamphlet called "Guidelines for the Practice of Religion" (Ton Chi Hanh Dao), in which he codified Hoa Hao cultic practices and for the first time imposed rules on admission into the sect. His adepts were exhorted to uphold the Three Bonds: between ruler and subject (transmuted into patriotism), father and son, and husband and wife. They were to observe the Five Virtues of benevolence, loyalty, propriety, intelligence, and integrity. Above all, they were to live in accord with one another. Whatever the usefulness of such a code of ethics in a modern, industrial society, it was quite effective within the confines of the average Hoa Hao village. Among themselves, the adepts relied on trust and did not bother to put doors on their houses to guard their belongings.[2]

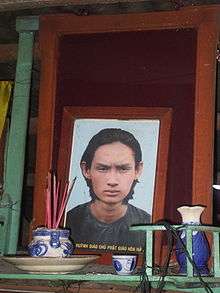

Death

Huynh Phu So was invited to a unity conference at a Viet Minh stronghold in the Plain of Reeds. On the way, he was led into a trap in which he and his four escorts were attacked but three were assassinated. The Viet Minh quartered his body and scattered it to prevent the Hoa Hao from recovering his remains and building a martyr's shrine. This rash and barbarous act resulted in a rupture incapable of subsequent reconciliation. The Hoa Hao vowed to wage eternal war against the Communists.[3]

Teachings

Impact

Hoa Hao religion combines the two kinds of Buddhism into one orientation: prescribing that all should strive to become monks for life but doing so at home and supporting themselves rather than turning into a caste of specialists permanently dependent on the community. The proscription on displaying Buddha statues on the household altar is borrowed from Islam’s proscription on the worship of images. The presence of a significant Islamic community in the local area has an impact on the Hoa Hao religion. A large community of ethnic Cham converts to Islam live in close proximity to Hoa Hao village. The surrounding area is full of mosques and its residents number many devout Muslims. Huynh Phu So, the founder of the Hoa Hao went to school in Tan Chau, in a heavily Muslim area. The influences are evident in the Hoa Hao’s religious practices; doctrine and architecture; the approach to prayer and preaching houses. A number of the towers, such as the one located by the Mekong River in Tan Chau town, have ornate sculpted decorations in an Islamic style and domed roofs. The Hoa Hao religion has been open to a range of different influences, including Marxism and US-style modernization ideology. For example, the combination of nationalist sentiments with the cult of heroes, the concept of a supreme being and US civic religion is found in this statement made by a contributor to a Hoa Hao Buddhist journal in the USA on the prospects for the democratization of Vietnam: I am praying to a higher power and to the sacred soul of the land, to the souls of heroes who have fallen on behalf of their beliefs and for the defense of the nation, so that they can prod and move and defeat this wave of atheism which is currently washing over Vietnam so that our people can welcome the light of Freedom and Democracy.[4]

Development

Return of the French colonial regime was a major disappointment to the Hoa Hao, as it was to Vietnamese nationalists of all political persuasions. Huynh Phu So had hoped that his sect would become the de facto ruling power throughout most of Cochinchina. But the return of the French in strength too numerous for the Hoa Hao "army" to oppose effectively put a temporary end to such hopes. The Hoa Hao turned their attention inward, both to solidify their sectarian strength and to increase their political influence in the delta. The French, becoming increasingly distrustful of the Viet Minh, soon gave the Hoa Hao territorial hegemony in the southwestern delta. Huynh Phu So for his part was willing to engage in alliances with the colonialists in return for support against the Viet Minh. Eventually the French provided arms for some 20,000 Hoa Hao troops. Such an accommodation was not considered by the Hoa Hao as a betrayal of their nationalist goals, because the ultimate aim of sectarian independence was not compromised. The Hoa Hao had long been suspicious of the National Front and the Viet Minh, and had actively fought the latter for years. The shift in loyalty from the colonialists to the National Front movement did not represent a major break for the Hoa Hao. As in their prior maneuverings, their action was primarily a move to solidify their own control of the western delta. Strengthened by French armaments, the Hoa Hao now turned against the French because they were convinced that colonial rule in Vietnam was destined to be ended by Asians. The Hoa Hao were certain that the French could and would be forced out of Indochina in the not-too-distinct future. But the Hoa Hao "alliance" with the Viet Minh was short-lived. It soon became clear that religious autonomy and the attendant political freedom demanded by the Hoa Hao were incompatible with Viet Minh plans. Before long, Huynh Phu So was preaching with growing frenzy against the Viet Minh, which he now perceived as an even greater threat to the sect than the French. The struggle with the Viet Minh became a fanatical religious war. So preached that any Hoa Hao killing ten Viet Minh would have a straight pathway to heaven. Although the Hoa Hao had an "army" of four combat battalions, they were eventually defeated by Saigon's much larger forces. The final Saigon victories in 1962 signaled the end of the independent Hao Hao army. But despite military defeat at the hands of Saigon, the Hoa Hao continued to maintain their religious and political hold over the territory west of the Bassac River and the delta capital city of Can Tho. They also held onto their arms, and organized militia forces to defend the geographical heartland of the movement. The Hoa Hao were too strong a force to allow the Saigon government the luxury of continued political or religious warfare. As a result, the Hoa Hao were thereafter left alone, and won tacit permission to maintain a kind of sovereignty in the Transbassac. In return, the Hoa Hao recognized the authority of the Saigon regime. No longer forced to devote their military forces to the struggle against the central government, they were able to resume their feud with the Communists. The Hoa Hao took full advantage of this new-found independence to wage total war against the Communists, now known as the Viet Cong. While political influence was welcome, the Hoa Hao had also achieved their primary goal-religious independence. Being a Hoa Hao was no longer a bar to participation in government, and the sect was no longer subject to religious discrimination by the orthodox Buddhist hierarchy. But it was the military strength of the Hoa Hao that gave the sect its strongest lever of influence, and its ability to provide a high degree of local security in the provinces it controlled. Huynh Phu So insisted on being referred to by his proper name of So and on using for his sect the name of his native village of Hoa Hao which meant "peace and plenty." He would no longer be one of many healers and preachers but the prophet of a distinct religious movement with its own name, built on the Buu Son Ky Huong tradition rather than simply part of it.[3]

The sect expanded rapidly under Japanese protection. Even though Huynh Phu So was unable to leave Saigon, his apostles recruited on his behalf, using the familiar mixture of doom-laden predictions and veiled threats against those who did not join and distributing cures and amulets. By 1943, the Hoa Hao sect was thus moving in the direction of greater institutionalization. The death of Huynh Phu So thus marked the end of the Hoa Hao millenarianism and the beginning of purely communal politics. Within the Hoa Hao communities, the preachers of old were replaced by lay administrators who were elected and unpaid. Healing was now the province of a health service operated free of charge by the sect. Evangelizing took the form of religious and academic education. The sect opened schools at all levels, and in the early 1970s it even established a university. Western technology in fact provided the sect with a new tool of mass education when the focus of Hoa Hao village life, the reading-room, was connected to a public-address system. The sayings of Patriarch Huynh were thus broadcast daily over loudspeakers. Charity also became organized: the sect offered relief for veterans and prisoners, for victims of floods and fire, for old people and orphans. Life in Hoa Hao villages continued to be led along simple lines. The adepts were guided by Huynh Phu So's teachings concerning cultic practices and daily conduct, and they kept the number of ceremonies low and the expenses connected with them minimal. Neither adepts nor leaders were particularly interested any longer in promoting radical change or even in pursuing the violent expansion of the sect. Their energies were now devoted to the preservation of the communitarian style of life which was the other Buu Son Ky Huong ideal. But communitarianism proved ill-suited to the social complexities of an urban environment. Furthermore, the adepts are virtually leaderless. The establishment of the sectarian infrastructure helped preserve their cohesion, but the corollary de-emphasis on charisma made it harder to mobilize the collectivity of the adepts into action.[2]

General features

The Hoa Hao works images of globes into their iconography which is an aesthetic expression of universalism reflecting an imagining of the spatial condition as global. This symbol has a mnemonic function as one of the four injunctions of the Hoa Hao faith is to recognize one’s debt to humanity. Yet it is also a reminder to followers that the propagation of the Hoa Hao faith is considered a sacred mission in order to reform mankind. This value is also reinforced in the prescribed color for the altar cloth and flag, which is brown. As brown is considered the combination of all colors, it is used to symbolize human harmony and the connectedness and interdependence of all people. Hoa Hao Buddhism is generally considered an apocalyptic religion: believers are held to anticipate the impending destruction of the world and seek refuge provided by faith. This illuminates the history of violence in which the Hoa Hao have been involved.[4]

Goal

The ultimate goal of the Hoa Hao religion is the preservation of their religious identity and independence. Temporary alliances with past enemies were formed only as a means of survival and to gain strength for the future. Originally concerned only with religious autonomy, the Hoa Hao became a nationalist anti-French movement before World War II; then increasingly anti-Communist as it struggled for supremacy with the Viet Minh; then overtly pro-Japanese for purely tactical reasons. With the end of the war, the Hoa Hao joined with their old enemy, the French colonialists, to strengthen themselves against a more serious foe, the Viet Minh. But the ultimate goal of the movement was always to control its own destiny without interference from any outside source.[3]

Followers

The earliest followers of the Hoa Hao were not just landless peasants impoverished by capitalism but small holders and there are those who work in transport, light industry and trade. The leaders of the Hoa Hao faith were recruited from schoolteachers, itinerant drivers and motor coach and river launch conductors, people on the nodes of the most important communicative pathways of colonial society. Today, some of the most cosmopolitan people in the delta, boat captains, traders, café owners and physicians, belong to this religion. Taylor has found members of the faith, like many residents of the Mekong Delta, to have wide horizons. They are informed about and engaged with current developments, interested in news of the outside world, focused on social work, improving the physical infrastructure of their locale and the building of a moral community.[4]

Followers' contributions

Of a less revolutionary order of activity, members of the faith are also very active in health care provision, community development activities and philanthropy. Such activities in accordance with the Master’s injunction to social engagement represent a viable and promising basis for the Hoa Hao to secure broader political support.[4]

Followers' thoughts about the future of the religion

The Hòa Hảo followers with whom Taylor spoke consider their home at the epicentre of world Buddhism, the Buddha having re-incarnated as Huynh Phu So. Many believe that Hoa Hao Buddhism spread from Vietnam to the rest of the world, following his overseas travels. In each land he visited the creed has been adapted to the local customs and is called by a different name. Today many members of the Hoa Hao still consider themselves engaged in a desperate struggle for survival, Some followers with whom Taylor spoke in Vietnam believed that the religion has recently secured limited recognition because of the large number of Hoa Hao believers who are in the local party and state administration quietly pushing for change.[4]

Reported persecution

Although Hòa Hảo Buddhism is an officially recognized religion in Vietnam, many members refuse the forceful governmental affiliation which is entailed by official recognition and an unknown number of religious leaders have been detained for this reason. Two Hòa Hảo Buddhists self-immolated in 2005 to protest against religious persecution and more recently, after a wave of arrests of Hòa Hảo Buddhists, nine more were imprisoned in May 2007.[5] Hòa Hảoists reportedly do not believe their founder died under torture. They surmise that he is still among the living. In 2007, the Vietnamese government had the printed prophesies of the founder seized and reprinted to a volume slightly more than half the original size. The ceremonies commemorating the birth of this prophet were outlawed. Since then, Hòa Hảo split into two factions – more and less militant.

Some Hòa Hảo adherents migrated to the United States. The largest number of Hòa Hảo-ists live in Santa Ana, California, USA.[6]

Hoa Hao claim to have faced restrictions on their religious and political activities after 1975, in part because of their previous armed opposition to Communist forces. A tentative easing of control on the religion began in 1999. There were, however, crackdowns in the face of demands that the government speed up this process. In 2001 there were again serious protests and arrests; a female member of the religion reportedly committed self-immolation to protest against restrictions on religious freedom[4]

Teachings

Hoa Hao Buddhism draws upon an earlier Buddhist millenarian movement called Bửu Sơn Kỳ Hương and reveres Đoàn Minh Huyên (14 November 1807 - 10 September 1856) who started the movement as a living, healing Buddha. He is referred to as Phật Thầy Tây An or "Buddha Master of the Western Peace". However, the founder of Hoa Hao Buddhism, Huynh Phu So, also organized Hoa Hao teachings into a more structured movement focused on self-cultivation, filial piety and reverence toward the Three Treasures of Buddhism (the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha).

As a lay-Buddhist organization primarily focused on Vietnamese peasants, it also eschews elaborate Buddhist rituals, maintains no monastic order, and teaches home practice.[7]

References

- Lei Hui-cui. A Preliminary Study of Hoahaoism. Department of the Vietnamese Language, School of Foreign Studies, University of International Business and Economics, Beijing, China.

- Ho Tai. MILLENARIANISM AND PEASANT POLITICS IN VIETNAM. Harvard University Press.

- Haseman (1976). "The Hoa Hao: A Half-Century of Conflict". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Taylor. "Apocalypse Now? Hoa Hao Buddhism Emerging from the Shadows of War". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "UNPO: Montagnards, Khmer Krom: Religious Intolerance Rewarded by UN". www.unpo.org. Archived from the original on 5 March 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-11-26. Retrieved 2013-07-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Dutton, George E.; Werner, Jayne S.; Whitmore, John K., eds. (2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Columbia University Press. p. 438. ISBN 0231511108.

Bibliography

- Ho Tai, Hue-Tam. Millenarianism and Peasant Politics in Vietnam. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1983.

- My-Van, Tran (2003). Beneath the Japanese Umbrella: Vietnam's Hòa Hào during and after the Pacific War, Crossroads: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 17 (1), 60-107

- Nguyễn Long Thành Nam. Hòa Hảo Buddhism in the Course of Việtnam's History. NY: Nova Science Publishing, 2004.

- Phạm Bích Hợp. Làng Hòa Hảo Xưa và Này (Hòa Hảo Village Past and Present) Ho Chi Minh City: Nha Xuat Ban Thanh Pho Ho Chi Minh, 1999.

- Taylor, Philip. "Apocalypse Now? Hòa Hảo Buddhism Emerging from the Shadows of War", The Australian Journal of Anthropology, Vol. 12, No. 3 (2001): 339-354.

- John B. Haseman. "The Hoa Hao: A Half-Century of Conflict", Asian Affairs, Vol. 3, No. 6, 373-383.