Karlsruhe

Karlsruhe (/ˈkɑːrlzruːə/, also US: /ˈkɑːrls-/,[2][3][4] German: [ˈkaʁlsˌʁuːə] (![]()

Karlsruhe | |

|---|---|

Karlsruhe Palace, view over Karlsruhe, Schlossplatz, Konzerthaus, Crown of Baden | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

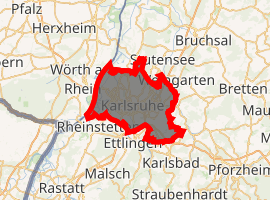

Location of Karlsruhe

| |

Karlsruhe  Karlsruhe | |

| Coordinates: 49°00′33″N 8°24′14″E | |

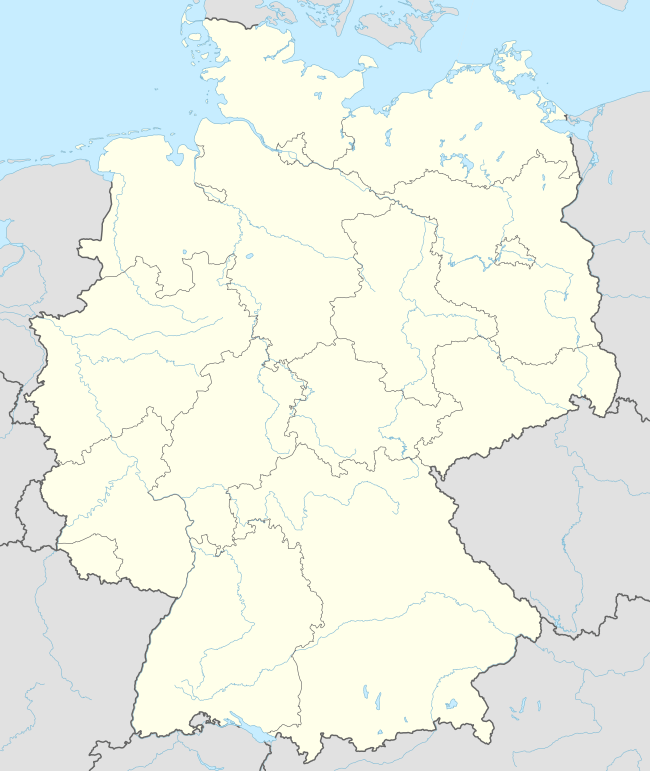

| Country | Germany |

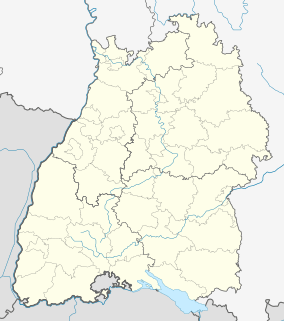

| State | Baden-Württemberg |

| Admin. region | Karlsruhe |

| District | Urban district |

| Founded | 1715 |

| Subdivisions | 27 quarters |

| Government | |

| • Lord Mayor | Frank Mentrup (SPD) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 173.46 km2 (66.97 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 115 m (377 ft) |

| Population (2018-12-31)[1] | |

| • Total | 313,092 |

| • Density | 1,800/km2 (4,700/sq mi) |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) |

| Postal codes | 76131–76229 |

| Dialling codes | 0721 |

| Vehicle registration | KA |

| Website | www.karlsruhe.de |

Karlsruhe was the capital of the Margraviate of Baden-Durlach (Durlach: 1565–1718; Karlsruhe: 1718–1771), the Margraviate of Baden (1771–1803), the Electorate of Baden (1803–1806), the Grand Duchy of Baden (1806–1918), and the Republic of Baden (1918–1945). Its most remarkable building is Karlsruhe Palace, which was built in 1715. There are nine institutions of higher education in the city, most notably the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (Karlsruher Institut für Technologie). Karlsruhe/Baden-Baden Airport (Flughafen Karlsruhe/Baden-Baden) is the second-busiest airport of Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart Airport, and the 17th-busiest airport of Germany.

In 2019 the UNESCO announced that Karlsruhe will join its network of "Creative Cities" as "City of Media Arts".[5][6]

Geography

Karlsruhe lies completely to the east of the Rhine, and almost completely on the Upper Rhine Plain. It contains the Turmberg in the east, and also lies on the borders of the Kraichgau leading to the Northern Black Forest.

The Rhine, one of the world's most important shipping routes, forms the western limits of the city, beyond which lie the towns of Maximiliansau and Wörth am Rhein in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate. The city centre is about 7.5 km (4.7 mi) from the river, as measured from the Marktplatz (Market Square). Two tributaries of the Rhine, the Alb and the Pfinz, flow through the city from the Kraichgau to eventually join the Rhine.

The city lies at an altitude between 100 and 322 m (near the communications tower in the suburb of Grünwettersbach). Its geographical coordinates are 49°00′N 8°24′E; the 49th parallel runs through the city centre, which puts it at the same latitude as much of the Canada–United States border, the cities Vancouver (Canada), Paris (France), Regensburg (Germany), and Hulunbuir (China). Its course is marked by a stone and painted line in the Stadtgarten (municipal park). The total area of the city is 173.46 km2 (66.97 sq mi), hence it is the 30th largest city in Germany measured by land area. The longest north-south distance is 16.8 km (10.4 mi) and 19.3 km (12.0 mi) in the east-west direction.

Karlsruhe is part of the urban area of Karlsruhe/Pforzheim, to which certain other towns in the district of Karlsruhe such as Bruchsal, Ettlingen, Stutensee, and Rheinstetten, as well as the city of Pforzheim, belong.

The city was planned with the palace tower (Schloss) at the center and 32 streets radiating out from it like the spokes of a wheel, or the ribs of a folding fan, so that one nickname for Karlsruhe in German is the "fan city" (Fächerstadt). Almost all of these streets survive to this day. Because of this city layout, in metric geometry, Karlsruhe metric refers to a measure of distance that assumes travel is only possible along radial streets and along circular avenues around the centre.[7]

The city centre is the oldest part of town and lies south of the palace in the quadrant defined by nine of the radial streets. The central part of the palace runs east-west, with two wings, each at a 45° angle, directed southeast and southwest (i.e., parallel with the streets marking the boundaries of the quadrant defining the city center).

The market square lies on the street running south from the palace to Ettlingen. The market square has the town hall (Rathaus) to the west, the main Lutheran church (Evangelische Stadtkirche) to the east, and the tomb of Margrave Charles III William in a pyramid in the buildings, resulting in Karlsruhe being one of only three large cities in Germany where buildings are laid out in the neoclassical style.

The area north of the palace is a park and forest. Originally the area to the east of the palace consisted of gardens and forests, some of which remain, but the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (founded in 1825), Wildparkstadion football stadium, and residential areas have been built there. The area west of the palace is now mostly residential.

Climate

Karlsruhe experiences an oceanic climate (Köppen Cfb) and its winter climate is milder, compared to most other German cities, except for the Rhine-Ruhr area. Summers are also hotter than elsewhere in the country and it is one of the sunniest cities in Germany, like the Rhine-Palatinate area. Precipitation is almost evenly spread throughout the year. In 2008, the weather station in Karlsruhe, which had been operating since 1876, was closed; it was replaced by a weather station in Rheinstetten, south of Karlsruhe.[8]

| Climate data for Rheinstetten, elevation: 112 m, 1981–2010 normals.[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1948-2013 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.5 (63.5) |

22.0 (71.6) |

26.7 (80.1) |

29.2 (84.6) |

33.3 (91.9) |

37.2 (99.0) |

38.5 (101.3) |

40.2 (104.4) |

32.8 (91.0) |

29.5 (85.1) |

21.8 (71.2) |

19.2 (66.6) |

40.2 (104.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

6.8 (44.2) |

11.7 (53.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

20.9 (69.6) |

24.0 (75.2) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.5 (79.7) |

21.6 (70.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

9.1 (48.4) |

5.5 (41.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.0 (35.6) |

3.0 (37.4) |

6.9 (44.4) |

10.7 (51.3) |

15.2 (59.4) |

18.3 (64.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

20.1 (68.2) |

15.6 (60.1) |

10.9 (51.6) |

5.8 (42.4) |

2.9 (37.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.7 (30.7) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

2.7 (36.9) |

5.3 (41.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.8 (55.0) |

14.9 (58.8) |

14.6 (58.3) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

2.9 (37.2) |

0.4 (32.7) |

6.7 (44.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −20.0 (−4.0) |

−15.0 (5.0) |

−14.6 (5.7) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

3.6 (38.5) |

6.9 (44.4) |

6.3 (43.3) |

2.5 (36.5) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−9.3 (15.3) |

−18.7 (−1.7) |

−20.0 (−4.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 58.0 (2.28) |

55.8 (2.20) |

59.0 (2.32) |

52.7 (2.07) |

77.6 (3.06) |

76.4 (3.01) |

75.3 (2.96) |

58.7 (2.31) |

57.9 (2.28) |

73.5 (2.89) |

63.3 (2.49) |

75.2 (2.96) |

783.4 (30.84) |

| Average precipitation days | 15.4 | 12.2 | 14.3 | 12.9 | 13.5 | 14.6 | 12.1 | 10.3 | 10.7 | 13.5 | 14.0 | 15.6 | 159.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 56.7 | 87.8 | 131.2 | 182.7 | 218.4 | 232.1 | 253.9 | 237.3 | 174.4 | 110.9 | 65.5 | 45.6 | 1,796.4 |

| Source 1: DWD[10] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Climatebase.ru[9] | |||||||||||||

History

According to legend, the name Karlsruhe, which translates as "Charles’ repose" or "Charles' peace", was given to the new city after a hunting trip when Margrave Charles III William of Baden-Durlach woke from a dream in which he dreamt of founding his new city. A variation of this story claims that he built the new palace to find peace from his wife.

Charles William founded the city on June 17, 1715, after a dispute with the citizens of his previous capital, Durlach. The founding of the city is closely linked to the construction of the palace. Karlsruhe became the capital of Baden-Durlach, and, in 1771, of the united Baden until 1945. Built in 1822, the Ständehaus was the first parliament building in a German state. In the aftermath of the democratic revolution of 1848, a republican government was elected there.

Karlsruhe was visited by Thomas Jefferson during his time as the American envoy to France; when Pierre Charles L'Enfant was planning the layout of Washington, D.C., Jefferson passed to him maps of 12 European towns to consult, one of which was a sketch he had made of Karlsruhe during his visit.[11]

In 1860, the first-ever international professional convention of chemists, the Karlsruhe Congress, was held in the city.[12]

Much of the central area, including the palace, was reduced to rubble by Allied bombing during World War II, but was rebuilt after the war. Located in the American zone of the postwar Allied occupation, Karlsruhe was home to an American military base, established in 1945. In 1995, the bases closed, and their facilities were turned over to the city of Karlsruhe.[13]

Population

The following list shows the most significant groups of foreigners residing in the city of Karlsruhe by country.

| Rank | Nationality | Population (31 December 2016)[14] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5,672 | |

| 2 | 5,657 | |

| 3 | 4,472 | |

| 4 | 3,153 | |

| 5 | 3,013 | |

| 6 | 2,579 | |

| 7 | 1,893 | |

| 8 | 1,743 | |

| 9 | 1,491 | |

| 10 | 1,336 | |

| 11 | 1,190 | |

| 12 | 1,176 | |

| 13 | 1,122 | |

| 14 | 1,115 | |

| 15 | 1,104 | |

| 16 | 892 |

Main sights

The Stadtgarten is a recreational area near the main railway station (Hauptbahnhof) and was rebuilt for the 1967 Federal Garden Show (Bundesgartenschau). It is also the site of the Karlsruhe Zoo.

The Durlacher Turmberg has a look-out tower (hence its name). It is a former keep dating back to the 13th century.

The city has two botanical gardens: the municipal Botanischer Garten Karlsruhe, which forms part of the Palace complex, and the Botanischer Garten der Universität Karlsruhe, which is maintained by the university.

The Marktplatz has a stone pyramid marking the grave of the city's founder. Built in 1825, it is the emblem of Karlsruhe. The city is nicknamed the "fan city" (die Fächerstadt) because of its design layout, with straight streets radiating fan-like from the Palace.

The Karlsruhe Palace (Schloss) is an interesting piece of architecture; the adjacent Schlossgarten includes the Botanical Garden with a palm, cactus and orchid house, and walking paths through the woods to the north.

The so-called Kleine Kirche (Little Church), built between 1773 and 1776, is the oldest church of Karlsruhe's city centre.

The architect Friedrich Weinbrenner designed many of the city's most important sights. Another sight is the Rondellplatz with its 'Constitution Building Columns' (1826). It is dedicated to Baden's first constitution in 1818, which was one of the most liberal of its time. The Münze (mint), erected in 1826/27, was also built by Weinbrenner.

The St. Stephan parish church is one of the masterpieces of neoclassical church architecture in.[15] Weinbrenner, who built this church between 1808 and 1814, orientated it to the Pantheon, Rome.

The neo-Gothic Grand Ducal Burial Chapel, built between 1889 and 1896, is a mausoleum rather than a church, and is located in the middle of the forest.

The main cemetery of Karlsruhe is the oldest park-like cemetery in Germany. The crematorium was the first to be built in the style of a church.

Karlsruhe is also home to a natural history museum (the State Museum of Natural History Karlsruhe), an opera house (the Baden State Theatre), as well as a number of independent theatres and art galleries. The State Art Gallery, built in 1846 by Heinrich Hübsch, displays paintings and sculptures from six centuries, particularly from France, Germany and Holland. Karlsruhe's newly renovated art museum is one of the most important art museums in Baden-Württemberg. Further cultural attractions are scattered throughout Karlsruhe's various incorporated suburbs. Established in 1924, the Scheffel Association is the largest literary society in Germany. Today the Prinz-Max-Palais, built between 1881 and 1884 in neoclassical style, houses the organisation and includes its museum.

Due to population growth in the late 19th century, Karlsruhe developed several suburban areas (Vorstadt) in the Gründerzeit and especially art nouveau styles of architecture, with many preserved examples.

Karlsruhe is also home to the Majolika-Manufaktur,[16] the only art-ceramics pottery studio in Germany. Founded in 1901, it is located in the Schlossgarten. A 'blue streak' (Blauer Strahl) consisting of 1,645 ceramic tiles, connects the studio with the Palace. It is the world's largest ceramic artwork.

Another tourist attraction is the Centre for Art and Media (Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie, or ZKM), which is located in a converted ammunition factory.

Government

Justice

Karlsruhe is the seat of the German Federal Constitutional Court (Bundesverfassungsgericht) and the highest Court of Appeals in civil and criminal cases, the Bundesgerichtshof. The courts came to Karlsruhe after World War II, when the provinces of Baden and Württemberg were merged. Stuttgart, capital of Württemberg, became the capital of the new province (Württemberg-Baden in 1945 and Baden-Württemberg in 1952). In compensation for the state authorities relocated to Stuttgart, Karlsruhe applied to become the seat of the high court.[17]

Public health

There are four hospitals: The municipal Klinikum Karlsruhe provides the maximum level of medical services, the St. Vincentius-Kliniken and the Diakonissenkrankenhaus, connected to the Catholic and Protestant churches, respectively, offer central services, and the private Paracelsus-Klinik basic medical care, according to state hospital demand planning.

Economy

Germany's largest oil refinery is located in Karlsruhe, at the western edge of the city, directly on the river Rhine. The Technologieregion Karlsruhe is a loose confederation of the region's cities in order to promote high tech industries; today, about 20% of the region's jobs are in research and development. EnBW, one of Germany's biggest electric utility companies and a revenue of 19.2 billion € in 2012,[18] is headquartered in the city.

Internet activities

Due to the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology providing services until the late 1990, Karlsruhe became known as the internet capital of Germany.[19] The DENIC, Germany's Network Information Centre, has since moved to Frankfurt, though, where DE-CIX is located.

Two major internet service providers, WEB.DE and schlund+partner/1&1, now both owned by United Internet AG, are located at Karlsruhe.

The library of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology developed the Karlsruher Virtueller Katalog, the first internet site that allowed researchers worldwide (for free) to search multiple library catalogues worldwide.

In the year 2000 the regional online "newspaper" ka‑news.de was created. As a daily newspaper, it not only provides the news, but also informs readers about upcoming events in Karlsruhe and surrounding areas.

In addition to established companies, Karlsruhe has a vivid and spreading startup community with well-known startups like STAPPZ.[20][21] Together, the local high tech industry is responsible for over 22.000 jobs.[22]

Transport

The Verkehrsbetriebe Karlsruhe (VBK) operates the city's urban public transport network, comprising seven tram routes and a network of bus routes. This network is well developed and all city areas can be reached round the clock by tram and a night bus system. The Turmbergbahn funicular railway, to the east of the city centre, is also operated by the VBK.

The VBK is also a partner, with the Albtal-Verkehrs-Gesellschaft and Deutsche Bahn, in the operation of the Karlsruhe Stadtbahn, the rail system that serves a larger area around the city. This system makes it possible to reach other towns in the region, like Ettlingen, Wörth am Rhein, Pforzheim, Bad Wildbad, Bretten, Bruchsal, Heilbronn, Baden-Baden, and even Freudenstadt in the Black Forest right from the city centre. The Stadtbahn is well known in transport circles around the world for pioneering the concept of operating trams on train tracks, to achieve a more effective and attractive public transport system, to the extent that this is often known as the Karlsruhe model tram-train system.

Karlsruhe is well-connected via road and rail, with Autobahn and Intercity Express connections going to Frankfurt, Stuttgart/Munich and Freiburg/Basel from Karlsruhe Hauptbahnhof. Since June 2007 it has been connected to the TGV network, reducing travel time to Paris to only three hours (previously it had taken five hours).

Two ports on the Rhine provide transport capacity on cargo ships, especially for petroleum products.

The nearest airport is part of the Baden Airpark (officially Flughafen Karlsruhe/Baden-Baden) about 45 km (28 mi) southwest of Karlsruhe, with regular connections to airports in Germany and Europe in general. Frankfurt International Airport can be reached in about an hour and a half by car (one hour by Intercity Express); Stuttgart Airport can be reached in about one hour (about an hour and a half by train and S‑Bahn).

Two interesting facts in transportation history are that both Karl Drais, the inventor of the bicycle, as well as Karl Benz, the inventor of the automobile were born in Karlsruhe. Benz was born in Mühlburg, which later became a borough of Karlsruhe (in 1886). Benz also studied at the Karlsruhe University. It also is interesting that Benz’s wife Bertha took the world's first long distance-drive with an automobile from Mannheim to Karlsruhe-Grötzingen and Pforzheim (see Bertha Benz Memorial Route). Their professional lives led both men to the neighboring city of Mannheim, where they first applied their most famous inventions.

Jewish community

Jews settled in Karlsruhe soon after its founding.[23] They were attracted by the numerous privileges granted by its founder to settlers, without discrimination as to creed. Official documents attest the presence of several Jewish families at Karlsruhe in 1717.[23] A year later the city council addressed to the margrave a report in which a question was raised as to the proportion of municipal charges to be borne by the newly arrived Jews, who in that year formed an organized congregation, with Rabbi Nathan Uri Kohen of Metz at its head. A document dated 1726 gives the names of twenty-four Jews who had taken part in an election of municipal officers.

As the city grew, permission to settle there became less easily obtained by Jews, and the community developed more slowly. A 1752 Jewry ordinance stated Jews were forbidden to leave the city on Sundays and Christian holidays, or to go out of their houses during church services, but they were exempted from service by court summonses on Sabbaths. They could sell wine only in inns owned by Jews and graze their cattle, not on the commons, but on the wayside only. Nethanael Weill was a rabbi in Karlsruhe from 1750 until his death.

In 1783, by a decree issued by Margrave Charles Frederick of Baden, the Jews ceased to be serfs, and consequently could settle wherever they pleased. The same decree freed them from the Todfall tax, paid to the clergy for each Jewish burial. In commemoration of these changes special prayers were prepared by the acting rabbi Jedidiah Tiah Weill, who, succeeding his father in 1770, held the office until 1805.

In 1808 the new constitution of what at that time, during the Napoleonic era, had become the Grand Duchy of Baden granted Jews citizenship status; a subsequent edict, in 1809, constitutionally acknowledged Jews as a religious group.[24][25] The latter edict provided for a hierarchical organization of the Jewish communities of Baden, under the umbrella of a central council of Baden Jewry (Oberrat der Israeliten Badens), with its seat in Karlsruhe,[24] and the appointment of a chief rabbi of Karlsruhe, as the spiritual head of the Jews in all of Baden.[23] The first chief rabbi of Karlsruhe and Baden was Rabbi Asher Loew, who served from 1809 until his death in 1837.[26]

Complete emancipation was given in 1862, Jews were elected to city council and Baden parliament, and from 1890 were appointed judges. Jews were persecuted in the 'Hep-Hep' riots that occurred in 1819; and anti-Jewish demonstrations were held in 1843, 1848, and the 1880s. The well-known German-Israeli artist Leo Kahn studied in Karlsruhe before leaving for France and Israel in the 1920s and 1930s.

Today, there are about 900 members in the Jewish community, many of whom are recent immigrants from Russia, and an orthodox rabbi.[27]

Karlsruhe has memorialized its Jewish community and notable pre-war synagogues with a memorial park.[28]

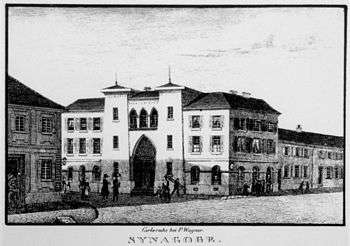

Karlsruhe Synagogue, built by Friedrich Weinbrenner in 1798, existed until 1871

Karlsruhe Synagogue, built by Friedrich Weinbrenner in 1798, existed until 1871 Holocaust memorial

Holocaust memorial The new synagogue

The new synagogue Public menorah on the Marktplatz

Public menorah on the Marktplatz

Karlsruhe and the Shoah

On 28 October 1938, all Jewish men of Polish extraction were expelled to the Polish border, their families joining them later and most ultimately perishing in the ghettoes and concentration camps. On Kristallnacht (9-10 November 1938), the Adass Jeshurun synagogue was burned to the ground, the main synagogue was damaged, and Jewish men were taken to the Dachau concentration camp after being beaten and tormented. Deportations commenced on 22 October 1940, when 893 Jews were loaded onto trains for the three-day journey to the Gurs concentration camp in France. Another 387 were deported in 1942-45 to lzbica in the Lublin district (Poland), Theresienstadt, and Auschwitz. Of the 1,280 Jews deported directly from Karlsruhe, 1,175 perished. Another 138 perished after deportation from other German cities or occupied Europe. In all, 1,421 of Karlsruhe’s Jews died during the Shoah. A new community was formed after the war by surviving former residents, with a new synagogue erected in 1971. It numbered 359 in 1980.[29]

Historical population

| Year | Inhabitants |

|---|---|

| 1719 | 2,000[30] |

| 1750 | 2,500[30] |

| 1815 | >15,000[30] |

| 1901 | 100,000[30] |

| 1933 | 155,000[30] |

| 1973 | 264,249[31] |

| 2003 | 282,595 |

| 2007 | 288,917 |

| 2012 | 296,033 |

| 2014 | 312,174[32] |

Famous people

- George Bayer, pioneer in the US state of Missouri

- Karl Benz (1844–1929), mechanical engineer and inventor of the first automobile as well as the founder of Benz & Co., Daimler-Benz, and Mercedes-Benz (now part of Daimler AG). He was born in the Karlsruhe borough of Mühlburg and educated at Karlsruhe Grammar School, the Lyceum, and Poly-Technical University

- Hermann Billing, Art Nouveau architect, was born and lived in Karlsruhe, where he built his first famous works

- Siegfried Buback, (1920–1977), then-Attorney General of Germany who fell victim to terrorists of the Rote Armee Fraktion in April 1977 in Karlsruhe

- Berthold von Deimling (1853-1944), Prussian general

- Karl Drais, (1785–1851), inventor of the two-wheeler principle basic to bicycle and motorcycle, key typewriter, and earliest stenograph, was born and died in Karlsruhe (1785–1851)

- Theodor von Dusch (1824–1890), physician remembered for experiments involving cotton-wool filters for bacteria

- Ludwig Eichrodt, writer

- Erik H. Erikson (1902-1994), children's psychoanalyst and theoretical pioneer in the field of study of identity building, spent his childhood and school time (Bismarck-Gymnasium) in Karlsruhe.

- Harry L. Ettlinger, US Army private who assisted the MFAA in the recovery of art looted by the Nazis. He was the last Jewish boy to celebrate his bar mitzvah in Karlsruhe's Kronenstrasse Synagogue, on September 24, 1938.

- Clara Mathilda Faisst (1872–1948), pianist and composer

- Hans Frank (1900–1946), Obergruppenführer SA, Gauleiter and governor-general of Nazi-occupied Poland; hanged at Nuremberg for his war crimes during World War II

- Reinhold Frank, (1896–1945), lawyer who worked for the resistance in Nazi Germany, ran a law practice in Karlsruhe; in his honour the street in Karlsruhe where the lawyer's chambers were founded bears his name

- Gottfried Fuchs (1889–1972), German-Canadian Olympic soccer player

- Karoline von Günderrode, poet, was born in Karlsruhe (1780–1806)

- Johann Peter Hebel, writer and poet, lived in Karlsruhe for most of his life

- Heinrich Rudolf Hertz: discovered electromagnetic waves at the University of Karlsruhe in the late 1880s. A lecture room named after Hertz lies close to the very spot where the discovery was made.

- Friedrich Hund, physicist of the pioneering generation of quantum mechanics (see Hund's rules); was born here

- Hedwig Kettler (1851–1937), founded the first German Mädchengymnasium (girls' high school), located in Karlsruhe

- Gustav Landauer, (1870–1919), theorist of anarchism in Germany, was born in Karlsruhe

- Markus Lüpertz worked and lives in Karlsruhe; he created the Narrenbrunnen (Fool's Fountain) in the city center

- Composer Wolfgang Rihm is a resident of Karlsruhe

- In 1886, Joseph Viktor von Scheffel, poet and novelist, was born in Karlsruhe

- Peter Sloterdijk, (born 1947), German philosopher

- Rahel Straus (1880–1963), German-Jewish medical doctor and feminist

- Johann Gottfried Tulla (born in 1770 in Karlsruhe): instrumental in stabilizing and straightening the course of the southern Rhine; a co-founder of the Karlsruhe University (1825)

- Victoria of Baden (1862–1930), born in Karlsruhe, queen consort of Sweden by her marriage to King Gustaf V of Sweden

- Friedrich Weinbrenner, (1766–1826) architect of neoclassicism; his tomb is situated in the main Protestant church in Karlsruhe

- Thomas Ernst Josef Wiedemann (1950–2001), German-British historian, born in Karlsruhe

- Richard Willstätter, recipient of 1915 Nobel Prize for Chemistry

Notable contemporary entertainment and sports figures

- Dennis Aogo, German football defender who currently plays for VfB Stuttgart

- Christa Bauch, female bodybuilder

- Walther Bensemann is one of the founders of the first southern German soccer club Karlsruher FV and later he became one of the founders of DFB and the founder of Kicker, which is Germany's leading soccer magazine

- Oliver Bierhoff, (born 1968), retired German football striker and former national team captain for the Germany and Italian Serie A clubs Udinese, A.C. Milan and Chievo; currently working as the German national team manager

- Andi Deris, (born 1964) German musician and songwriter, lead singer of the power metal band Helloween

- Karl Elzer, stage and film actor

- Gottfried Fuchs (1889–1972), was born in Karlsruhe and holds the record of ten goals in one single international soccer match for the German national team

- Regina Halmich, (born 1976), retired female boxing flyweight world champion

- Vincenzo Italiano, Italian footballer currently plays for Calcio Padova

- Sead Kolašinac (born 20 June 1993) is a Bosnian footballer who plays as a left back for Arsenal FC

- Oliver Kahn, (born 1969), retired goalkeeper of Karlsruher SC, Bayern Munich and Germany

- Sebastian Koch, (born 1962), German actor

- Renate Lingor, former German national football player

- Mehmet Scholl, (born 1970), German retired footballer for Karlsruher SC, later Bayern Munich and the German national team

- Susanne Stichler (born 1969), German journalist and television presenter

- Muhammed Suiçmez, (born 1975), Turkish guitarist and composer for German technical death metal band Necrophagist

- Eugene Weingand (1934–1986), actor and television host who claimed to be Peter Lorre Jr.

- Moon Gayoung, (born 1996), South Korea actress

Education

Karlsruhe is a renowned research and study centre, with one of Germany's finest institutions of higher education.

Technology, engineering, and business

The Karlsruhe University (Universität Karlsruhe-TH), the oldest technical university in Germany, is home to the Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe (Karlsruhe Research Center), where engineering and scientific research is performed in the areas of health, earth, and environmental sciences. The Karlsruhe University of Applied Sciences (Hochschule Karlsruhe-HS) is the largest university of technology in the state of Baden-Württemberg, offering both professional and academic education in engineering sciences and business. In 2009, the University of Karlsruhe joined the Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe to form the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT).

The arts

The Academy of Fine Arts, Karlsruhe is one of the smallest universities in Germany, with average 300 students, but it is known as one of the most significant academies of fine arts. The Karlsruhe University of Arts and Design (HfG) was founded to the same time as its sister institution, the Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe (Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie). The HfG teaching and research focuses on new media and media art. The Hochschule für Musik Karlsruhe is a music conservatory that offers degrees in composition, music performance, education, and radio journalism. Since 1989 it has been located in the Gottesaue Palace.

International education

The Karlshochschule International University (formerly known as Merkur Internationale Fachhochschule) was founded in 2004. As a foundation-owned, state-approved management school, Karlshochschule offers undergraduate education in both German and English, focusing on international and intercultural management, as well as service- and culture-related industries. Furthermore, an international consecutive Master of Arts in leadership studies is offered in English.

European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT)

Karlsruhe hosts one of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology's Knowledge and Innovation Communities (KICs) focusing on sustainable energy. Other co‑centres are based in Grenoble, France (CC Alps Valleys); Eindhoven, the Netherlands, and Leuven, Belgium (CC Benelux); Barcelona, Spain (CC Iberia); Kraków, Poland (CC PolandPlus); and Stockholm, Sweden (CC Sweden).[33]

University of Education

The Karlsruhe University of Education was founded in 1962. It is specialized in educational processes. The University has about 3700 students and 180 full-time researchers and lecturers. It offers a wide range of educational studies, like teaching profession for primary and secondary schools (both optional with a European Teaching Certificate profile), Bachelor programs that specializes in Early Childhood Education and in Health and Leisure Education, Master programs in Educational Science, Intercultural Education, Migration and Multilingualism. Furthermore, the University of Education Karlsruhe offers a Master program for Biodiversity and Environmental Education.[34]

Culture

In 1999 the ZKM (Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie, Centre for Art and Media) was opened. Within a short time it built up a worldwide reputation as a cultural institution. Linking new media theory and practice, the ZKM is located in a former weapons factory. Among the institutes related to the ZKM are the Staatliche Hochschule für Gestaltung (State University of Design), whose president is philosopher Peter Sloterdijk and the Museum for Contemporary Art.

International relations

Twin towns—sister cities

Karlsruhe is twinned with:[35]

Legacy

- Ukrainian village Stepove near the city of Mykolaiv in southern Ukraine was established by German colonists as Karlsruhe.

Events

Every year in July there is a large open-air festival lasting three days called simply Das Fest ("The Festival").[37][38]

The Baden State Theatre has sponsored the Händel Festival since 1978.

The city hosted the 23rd and 31st European Juggling Conventions (EJC) in 2000 and 2008.

In July the African Summer Festival is held in the city's Nordstadt. Markets, drumming workshops, exhibitions, a varied children's programme, and musical performances take place during the three days festival.[39]

In the past Karlsruhe has been the host of LinuxTag (the biggest Linux event in Europe) and until 2006 hosted the annual Linux Audio Conference.[40]

Visitors and locals watched the total solar eclipse at noon on August 11, 1999. The city was not only located within the eclipse path but was one of the few within Germany not plagued by bad weather.

Sport

- Football

- Karlsruher SC (KSC), DFB (2. Liga)

- Basketball

- PS Karlsruhe Lions, Basketball-Pro-Liga A (second division)

Karlsruhe co-hosted the FIBA EuroBasket 1985.

- Tennis

- TC Rueppurr (TCR), [Tennis-Bundesliga] (women's first division)

- Baseball, softball

- Karlsruhe Cougars, Regional League South-East (men's baseball), 1st Bundesliga South (women's softball I) and State League South (women's softball II)

- American football

- Badener Greifs, currently competing in the Regional League Central but formerly a member of the German Football League's 1st Bundesliga, lost to the Berlin Adler in the 1987 German Bowl (see also: German Football League)

Notes

- Except precipitation days which are for 1980-2012.[9]

References

- "Bevölkerung nach Nationalität und Geschlecht am 31. Dezember 2018". Statistisches Landesamt Baden-Württemberg (in German). July 2019.

- "Karlsruhe". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "Karlsruhe" (US) and "Karlsruhe". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "Karlsruhe". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "Karlsruhe | Creative Cities Network". en.unesco.org. Retrieved 2020-01-08.

- "Zwei deutsche Städte ins Netzwerk der UNESCO-Creative Cities aufgenommen | Deutsche UNESCO-Kommission". unesco.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-01-08.

- Rashid Bin Muhammad. "Karlsruhe-Metric Voronoi Diagram". Personal.kent.edu. Retrieved 2011-04-07.

- "Die Wetterstationen in Karlsruhe". Wetter.im-licht-der-natur.de. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Карлсруэ, Баден-Вюртемберг, Германия #10727". climatebase.ru. Retrieved 2019-08-06.

- "Ausgabe der Klimadaten: Monatswerte".

- Volker C. Ihle (2011). Karlsruhe and the United States. Sonstige. pp. 35–37.

- Ihde, Aaron J. (February 1961). "The Karlsruhe Congress: A centennial retrospective". Journal of Chemical Education. 38 (2): 83–86. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- Elkins, Walter. "U.S. Army Installations - Karlsruhe". U.S. Army in Germany. Retrieved 2012-07-21.

- "Statistisches Jahrbuch 2017" (PDF). Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- Southern Germany

- Staatliche Majolika Manufaktur Karlsruhe GmbH. "Majolika-Manufaktur". Majolika-karlsruhe.com. Retrieved 2011-04-07.

- Stadt Karlsruhe Stadtarchiv (ed.): Karlsruhe. Die Stadtgeschichte. Badenia, Karlsruhe 1998, ISBN 3-7617-0353-8, p. 591–594

- "Financial Report 2012" (PDF). EnBW. p. 3.

- See , a webpage by the Federal Foreign Office

- "Interview mit einem Gründer aus Karlsruhe". Retrieved 2015-05-08.

- "STAPPZ App from Karlsruhe, Homepage". Retrieved 2015-05-08.

- "Region: Mittlerer Oberrhein Informationstechnologie, IT-Anwendungen / Unternehmenssoftware". Retrieved 2015-05-08.

- "Karlsruhe (Carlsruhe)" (1906). The Jewish Encyclopedia. Ed. Isidore Singer. Vol. 7. p. 448-449.

- Dubnow, Simon (1920). Die neueste Geschichte des Jüdischen Volkes (1789-1914). (in German) Translated from the Russian by Alexander Eliasberg. Vol. 1. Einleitung. Erste Abteilung: Das Zeitalter der ersten Emanzipation (1789-1815). Berlin: Jüdischer Verlag. p. 288.

- Kober, Adolf (1942). "Mannheim." The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia. Ed. Isaac Landman. Vol. 7. New York: Universal Jewish Encyclopedia, Inc. p. 330-332; here: p. 331.

- Oelsner, Toni (2007). "Karlsruhe." Encyclopaedia Judaica. 2nd ed. Vol. 11. Detroit: Macmillan Reference. p. 810-811.

- "Jewish Community Karlsruhe - Karlsruhe, Germany".

- "images/Images%2021/ka%20syn". alemannia-judaica.de. Retrieved 2014-07-24.

- http://db.yadvashem.org/deportation/place.html?language=en&itemId=5433380

- Bräunche, Ernst Otto; Koch, Manfred (2015-04-16). "Karlsruher Stadtgeschichte". Stadtarchiv & Historische Museen (in German). Stadt Karlsruhe. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- "Eingliederung ehemals selbständiger Gemeinden". Amt für Stadtentwicklung (in German). Stadt Karlsruhe. 2010-06-07. Archived from the original on 2011-12-22. Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- http://web1.karlsruhe.de/Stadtentwicklung/siska/pdf/Bevoelkerung%202014-06.pdf%5B%5D

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-22. Retrieved 2009-12-19.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Karlsruhe University of Education". ph-karlsruhe.de. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- "Partnerstädte". karlsruhe.de (in German). Karlsruhe. Retrieved 2019-11-26.

- "Partneri- ja kummikaupungit (Partnership and twinning cities)". Oulun kaupunki (City of Oulu) (in Finnish). Retrieved 2013-07-27.

- "das FEST". Retrieved 2015-04-01.

- "das FEST" (in German). Retrieved 2011-01-05.

- "Karlsruhe Afrikamarkt & Festival 2011". Africansummerfestival.de. Retrieved 2011-04-07.

- "http://lac.zkm.de/". lac.zkm.de. Retrieved 2014-07-24. External link in

|title=(help)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Karlsruhe. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Karlsruhe. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Karlsruhe. |

- Official website

- Map of Karlsruhe

- City wiki of Karlsruhe (in German and English)

- Karlsruhe Nuclide Chart

-Portrait-Portr_07881.tif.jpg)