Hematite

Hematite, also spelled as haematite, is a common iron oxide with a formula of Fe2O3 and is widespread in rocks and soils.[5] Hematite forms in the shape of crystals through the rhombohedral lattice system, and it has the same crystal structure as ilmenite and corundum. Hematite and ilmenite form a complete solid solution at temperatures above 950 °C (1,740 °F).

| Hematite | |

|---|---|

Brazilian trigonal hematite crystal | |

| General | |

| Category | Oxide minerals |

| Formula (repeating unit) | iron(III) oxide, Fe2O3, α-Fe2O3[1] |

| Strunz classification | 4.CB.05 |

| Dana classification | 4.3.1.2 |

| Crystal system | Trigonal |

| Crystal class | Hexagonal scalenohedral (3m) H–M symbol: (3 2/m) |

| Space group | R3c |

| Unit cell | a = 5.038(2) Å; c = 13.772(12) Å; Z = 6 |

| Identification | |

| Color | Metallic gray, dull to bright "rust-red" in earthy, compact, fine-grained material, steel-grey to black in crystals and massively crystalline ores |

| Crystal habit | Tabular to thick crystals; micaceous or platy, commonly in rosettes; radiating fibrous, reniform, botryoidal or stalactitic masses, columnar; earthy, granular, oolitic |

| Twinning | Penetration and lamellar |

| Cleavage | None, may show partings on {0001} and {1011} |

| Fracture | Uneven to sub-conchoidal |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 5.5–6.5 |

| Luster | Metallic to splendent |

| Streak | Bright red to dark red |

| Diaphaneity | Opaque |

| Specific gravity | 5.26 |

| Density | 5.3 |

| Optical properties | Uniaxial (−) |

| Refractive index | nω = 3.150–3.220, nε = 2.870–2.940 |

| Birefringence | δ = 0.280 |

| Pleochroism | O = brownish red; E = yellowish red |

| References | [2][3][4] |

Hematite is colored black to steel or silver-gray, brown to reddish-brown, or red. It is mined as the main ore of iron. Varieties include kidney ore, martite (pseudomorphs after magnetite), iron rose and specularite (specular hematite). While these forms vary, they all have a rust-red streak. Hematite is harder than pure iron, but much more brittle. Maghemite is a hematite- and magnetite-related oxide mineral.

Large deposits of hematite are found in banded iron formations. Gray hematite is typically found in places that can have still, standing water or mineral hot springs, such as those in Yellowstone National Park in North America. The mineral can precipitate out of water and collect in layers at the bottom of a lake, spring, or other standing water. Hematite can also occur without water, usually as the result of volcanic activity.

Clay-sized hematite crystals can also occur as a secondary mineral formed by weathering processes in soil, and along with other iron oxides or oxyhydroxides such as goethite, is responsible for the red color of many tropical, ancient, or otherwise highly weathered soils.

Etymology and history

The name hematite is derived from the Greek word for blood αἷμα (haima), due to the red coloration found in some varieties of hematite.[5] The color of hematite lends itself to use as a pigment. The English name of the stone is derived from Middle French hématite pierre, which was imported from Latin lapis haematites c. the 15th century, which originated from Ancient Greek αἱματίτης λίθος (haimatitēs lithos, "blood-red stone").

Ochre is a clay that is colored by varying amounts of hematite, varying between 20% and 70%.[6] Red ochre contains unhydrated hematite, whereas yellow ochre contains hydrated hematite (Fe2O3 · H2O). The principal use of ochre is for tinting with a permanent color.[6]

The red chalk writing of this mineral was one of the earliest in the history of humans. The powdery mineral was first used 164,000 years ago by the Pinnacle-Point man, possibly for social purposes.[7] Hematite residues are also found in graves from 80,000 years ago. Near Rydno in Poland and Lovas in Hungary red chalk mines have been found that are from 5000 BC, belonging to the Linear Pottery culture at the Upper Rhine.[8]

Rich deposits of hematite have been found on the island of Elba that have been mined since the time of the Etruscans.

Magnetism

Hematite is an antiferromagnetic material below the Morin transition at 250 K (−23 °C), and a canted antiferromagnet or weakly ferromagnetic above the Morin transition and below its Néel temperature at 948 K (675 °C), above which it is paramagnetic.

The magnetic structure of α-hematite was the subject of considerable discussion and debate during the 1950s, as it appeared to be ferromagnetic with a Curie temperature of approximately 1,000 K (730 °C), but with an extremely small magnetic moment (0.002 Bohr magnetons). Adding to the surprise was a transition with a decrease in temperature at around 260 K (−13 °C) to a phase with no net magnetic moment. It was shown that the system is essentially antiferromagnetic, but that the low symmetry of the cation sites allows spin–orbit coupling to cause canting of the moments when they are in the plane perpendicular to the c axis. The disappearance of the moment with a decrease in temperature at 260 K (−13 °C) is caused by a change in the anisotropy which causes the moments to align along the c axis. In this configuration, spin canting does not reduce the energy.[9][10] The magnetic properties of bulk hematite differ from their nanoscale counterparts. For example, the Morin transition temperature of hematite decreases with a decrease in the particle size. The suppression of this transition has been observed in hematite nanoparticles and is attributed to the presence of impurities, water molecules and defects in the crystals lattice. Hematite is part of a complex solid solution oxyhydroxide system having various contents of water, hydroxyl groups and vacancy substitutions that affect the mineral's magnetic and crystal chemical properties.[11] Two other end-members are referred to as protohematite and hydrohematite.

Enhanced magnetic coercivities for hematite have been achieved by dry-heating a two-line ferrihydrite precursor prepared from solution. Hematite exhibited temperature-dependent magnetic coercivity values ranging from 289 to 5,027 oersteds (23–400 kA/m). The origin of these high coercivity values has been interpreted as a consequence of the subparticle structure induced by the different particle and crystallite size growth rates at increasing annealing temperature. These differences in the growth rates are translated into a progressive development of a subparticle structure at the nanoscale. At lower temperatures (350–600 °C), single particles crystallize however; at higher temperatures (600–1000 °C), the growth of crystalline aggregates with a subparticle structure is favored.[12]

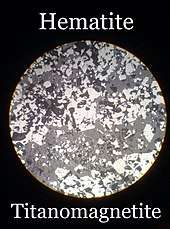

A microscopic picture of hematite

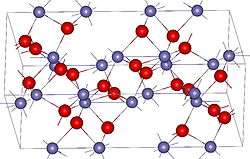

A microscopic picture of hematite Crystal structure of hematite

Crystal structure of hematite

Mine tailings

Hematite is present in the waste tailings of iron mines. A recently developed process, magnetation, uses magnets to glean waste hematite from old mine tailings in Minnesota's vast Mesabi Range iron district.[13] Falu red is a pigment used in traditional Swedish house paints. Originally, it was made from tailings of the Falu mine.[14]

Mars

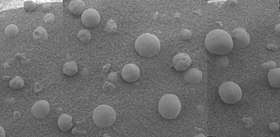

The spectral signature of hematite was seen on the planet Mars by the infrared spectrometer on the NASA Mars Global Surveyor[15] and 2001 Mars Odyssey spacecraft in orbit around Mars. The mineral was seen in abundance at two sites[16] on the planet, the Terra Meridiani site, near the Martian equator at 0° longitude, and the Aram Chaos site near the Valles Marineris.[17] Several other sites also showed hematite, such as Aureum Chaos.[18] Because terrestrial hematite is typically a mineral formed in aqueous environments or by aqueous alteration, this detection was scientifically interesting enough that the second of the two Mars Exploration Rovers was sent to a site in the Terra Meridiani region designated Meridiani Planum. In-situ investigations by the Opportunity rover showed a significant amount of hematite, much of it in the form of small spherules that were informally named "blueberries" by the science team. Analysis indicates that these spherules are apparently concretions formed from a water solution. "Knowing just how the hematite on Mars was formed will help us characterize the past environment and determine whether that environment was favorable for life".[19]

Jewelry

Hematite's popularity in jewelry rose in England during the Victorian era, due to its use in mourning jewelry.[20][21] Certain types of hematite- or iron-oxide-rich clay, especially Armenian bole, have been used in gilding. Hematite is also used in art such as in the creation of intaglio engraved gems. Hematine is a synthetic material sold as magnetic hematite.[22]

Gallery

- A rare pseudo-scalenohedral crystal habit

Three gemmy quartz crystals containing bright rust-red inclusions of hematite, on a field of sparkly black specular hematite

Three gemmy quartz crystals containing bright rust-red inclusions of hematite, on a field of sparkly black specular hematite Golden acicular crystals of rutile radiating from a center of platy hematite

Golden acicular crystals of rutile radiating from a center of platy hematite Cypro-Minoan cylinder seal (left) made from hematite with corresponding impression (right), approximately 14th century BC

Cypro-Minoan cylinder seal (left) made from hematite with corresponding impression (right), approximately 14th century BC A cluster of parallel-growth, mirror-bright, metallic-gray hematite blades from Brazil

A cluster of parallel-growth, mirror-bright, metallic-gray hematite blades from Brazil Hematite carving, 5 cm (2 in) long

Hematite carving, 5 cm (2 in) long Hematite, variant specularite (specular hematite), with fine grain shown

Hematite, variant specularite (specular hematite), with fine grain shown Red hematite from banded iron formation in Wyoming

Red hematite from banded iron formation in Wyoming Hematite on Mars as found in form of "blueberries" (named by Nasa)

Hematite on Mars as found in form of "blueberries" (named by Nasa) Streak plate, showing that Hematite consistently leaves a rust-red streak.

Streak plate, showing that Hematite consistently leaves a rust-red streak.- Hematite in Scanning Electron Microscope, magnification 100x.

See also

References

- Dunlop, David J.; Özdemir, Özden (2001). Rock Magnetism: Fundamentals and Frontiers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 73. ISBN 9780521000987.

- Anthony, John W.; Bideaux, Richard A.; Bladh, Kenneth W.; Nichols, Monte C. (eds.). "Hematite" (PDF). Handbook of Mineralogy. III. Chantilly, VA: Mineralogical Society of America. ISBN 978-0962209727. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- "Hematite Mineral Data". WebMineral.com. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- "Hematite". Mindat.org. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- Cornell, Rochelle M.; Schwertmann, Udo (1996). The Iron Oxides. Germany: Wiley. pp. 4, 26. ISBN 9783527285761. LCCN 96031931. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- "Ochre". Industrial Minerals. Minerals Zone. Archived from the original on November 15, 2016. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- "Researchers find earliest evidence for modern human behavior in South Africa" (Press release). AAAS. ASU News. October 17, 2007. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- Levato, Chiara (2016). "Iron Oxides Prehistoric Mines: A European Overview" (PDF). Anthropologica et Præhistorica. 126: 9–23. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- Dzyaloshinsky, I. E. (1958). "A thermodynamic theory of "weak" ferromagnetism of antiferromagnetics". Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids. 4 (4): 241–255. Bibcode:1958JPCS....4..241D. doi:10.1016/0022-3697(58)90076-3.

- Moriya, Tōru (1960). "Anisotropic Superexchange Interaction and Weak Ferromagnetism" (PDF). Physical Review. 120 (1): 91. Bibcode:1960PhRv..120...91M. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.120.91.

- Dang, M.-Z.; Rancourt, D. G.; Dutrizac, J. E.; Lamarche, G.; Provencher, R. (1998). "Interplay of surface conditions, particle size, stoichiometry, cell parameters, and magnetism in synthetic hematite-like materials". Hyperfine Interactions. 117 (1–4): 271–319. Bibcode:1998HyInt.117..271D. doi:10.1023/A:1012655729417.

- Vallina, B.; Rodriguez-Blanco, J. D.; Brown, A. P.; Benning, L. G.; Blanco, J. A. (2014). "Enhanced magnetic coercivity of α-Fe2O3 obtained from carbonated 2-line ferrihydrite" (PDF). Journal of Nanoparticle Research. 16 (3): 2322. Bibcode:2014JNR....16.2322V. doi:10.1007/s11051-014-2322-5.

- Redman, Chris (May 20, 2009). "The next iron rush". Money.cnn.com. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- "Sveriges mest beprövade husfärg" [Sweden's most proven house color] (in Northern Sami). Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- "Mars Global Surveyor TES Instrument Identification of Hematite on Mars" (Press release). NASA. May 27, 1998. Archived from the original on May 13, 2007. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- Bandfield, Joshua L. (2002). "Global mineral distributions on Mars" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 107 (E6): E65042. Bibcode:2002JGRE..107.5042B. doi:10.1029/2001JE001510.

- Glotch, Timothy D.; Christensen, Philip R. (2005). "Geologic and mineralogic mapping of Aram Chaos: Evidence for a water-rich history". Journal of Geophysical Research. 110 (E9): E09006. Bibcode:2005JGRE..110.9006G. doi:10.1029/2004JE002389.

- Glotch, Timothy D.; Rogers, D.; Christensen, Philip R. (2005). "A Newly Discovered Hematite-Rich Unit in Aureum Chaos: Comparison of Hematite and Associated Units With Those in Aram Chaos" (PDF). Lunar and Planetary Science. 36: 2159. Bibcode:2005LPI....36.2159G.

- "Hematite". NASA. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- "Black Gemstones, Diamonds and Opals: The Popular New Jewelry Trend". TrueFacet.com. October 23, 2015. Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- "(What's the Story) Mourning Jewelry?". Retrieved December 22, 2018.

- "Magnetic Hematite". Mindat.org. Retrieved December 22, 2018.