Cleavage (crystal)

Cleavage, in mineralogy, is the tendency of crystalline materials to split along definite crystallographic structural planes. These planes of relative weakness are a result of the regular locations of atoms and ions in the crystal, which create smooth repeating surfaces that are visible both in the microscope and to the naked eye.[1]

Types of cleavage

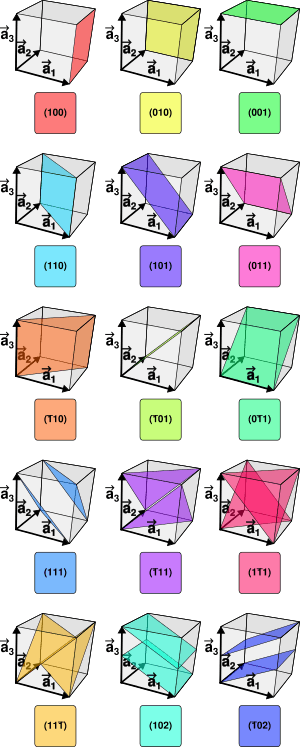

Cleavage forms parallel to crystallographic planes:[1]

- Basal or pinacoidal cleavage occurs when there is only one cleavage plane. Graphite has basal cleavage. Mica (like muscovite or biotite) also has basal cleavage; this is why mica can be peeled into thin sheets.

- Cubic cleavage occurs on when there are three cleavage planes intersecting at 90 degrees. Halite (or salt) has cubic cleavage, and therefore, when halite crystals are broken, they will form more cubes.

- Octahedral cleavage occurs when there are four cleavage planes in a crystal. Fluorite exhibits perfect octahedral cleavage. Octahedral cleavage is common for semiconductors. Diamond also has octahedral cleavage.

- Rhombohedral cleavage occurs when there are three cleavage planes intersecting at angles that are not 90 degrees. Calcite has rhombohedral cleavage.

- Prismatic cleavage occurs when there are two cleavage planes in a crystal. Spodumene exhibits prismatic cleavage.

- Dodecahedral cleavage occurs when there are six cleavage planes in a crystal. Sphalerite has dodecahedral cleavage.

Parting

Crystal parting occurs when minerals break along planes of structural weakness due to external stress or along twin composition planes. Parting breaks are very similar in appearance to cleavage, but only occur due to stress. Examples include magnetite which shows octahedral parting, the rhombohedral parting of corundum and basal parting in pyroxenes.[1]

Uses

Cleavage is a physical property traditionally used in mineral identification, both in hand specimen and microscopic examination of rock and mineral studies. As an example, the angles between the prismatic cleavage planes for the pyroxenes (88–92°) and the amphiboles (56–124°) are diagnostic.[1]

Crystal cleavage is of technical importance in the electronics industry and in the cutting of gemstones.

Precious stones are generally cleaved by impact, as in diamond cutting.

Synthetic single crystals of semiconductor materials are generally sold as thin wafers which are much easier to cleave. Simply pressing a silicon wafer against a soft surface and scratching its edge with a diamond scribe is usually enough to cause cleavage; however, when dicing a wafer to form chips, a procedure of scoring and breaking is often followed for greater control. Elemental semiconductors (Si, Ge, and diamond) are diamond cubic, a space group for which octahedral cleavage is observed. This means that some orientations of wafer allow near-perfect rectangles to be cleaved. Most other commercial semiconductors (GaAs, InSb, etc.) can be made in the related zinc blende structure, with similar cleavage planes.

See also

References

-

- Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Klein, Cornelis, 1985, Manual of Mineralogy, 20th ed., Wiley, ISBN 0-471-80580-7