Rocky Mountain Front

The Rocky Mountain Front is a somewhat unified geologic and ecosystem area in North America where the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains meet the plains.[1] In 1983, the Bureau of Land Management called the Rocky Mountain Front "a nationally significant area because of its high wildlife, recreation, and scenic values".[2] Conservationists Gregory Neudecker, Alison Duvall, and James Stutzman have described the Rocky Mountain Front as an area that warrants "the highest of conservation priorities" because it is largely unaltered by development and contains "unparalleled" numbers of wildlife.[3]

Defining the Rocky Mountain Front

Although the Rocky Mountain Front is clearly distinct from both plains and mountains, in places like the Wyoming Basin, Montana, and New Mexico it is more ambiguous.[4] One definition of the front is that it is a "transition zone between the Rocky Mountains and the mixed grass prairie ... [that] encompasses a wide variety of wetland, riparian, grassland, and forested habitats".[5] By one estimate there are more than 2,000,000 acres (8,100 km2) of Rocky Mountain Front land in Montana and Canada.[6]

The Rocky Mountain Front is such an important geologic feature that it affects the weather in North America. Warm air masses moving from the Gulf of Mexico are blocked by the front from moving west, causing hail, thunderstorms, tornadoes, and other kinds of violent weather which then move east. "Tornado Alley", that part of the Great Plains where tornadoes are most frequent, is a direct outcome of the front's effect on weather.[7]

Areas of the Rocky Mountain Front

British Columbia and Alberta

In Alberta, the Rocky Mountain Front is about 12 to 19 miles (19 to 31 km) wide.[8]

As early as 1935, it was well-recognized that significant coal resources underlay the Rocky Mountain Front in Alberta.[9] As of 2013, about 60 percent of all Canadian coal reserves are believed to be beneath the front in Alberta.[10] Natural gas is also very plentiful. Royal Dutch Shell began producing natural gas there in the Pincher Creek Gas Field in the 1950s, and built a sweetening plant there in 1957.[11] The Pincher Creek Gas Field can produce up to 150 million cubic feet of natural gas per day, and in the 1960s Shell Oil built a second sweetening plant near Waterton Lakes National Park.[12]

The Rocky Mountain Front in British Columbia and Alberta has long been inhabited by Plains Indians, and the area contains widely scattered but not uncommon Native American rock art sites.[13]

Development along the front is somewhat limited. In the 1940s, planners considered building the Alaska Highway along the Rocky Mountain Front in British Columbia and Alberta but ultimately decided on a coastal route.[14] In the early 2000s, the Nature Conservancy was working to secure environmental easements along the front in Alberta to protect grizzly bear habitat.[15]

Montana

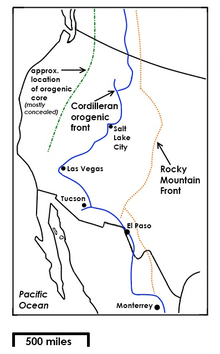

The Rocky Mountain Front in Montana from the Canada–US border south to about Helena is heavily deformed by faulting, folding, and overthrusting.[16] During the Sevier orogeny mountain-building event about 115 and 55 million years ago, what is known as the Cordilleran foreland thrust-and-fold event occurred along the east side of the Rocky Mountains in northwest Montana. The thrust-and-fold belt does not extend all the way south through Montana. Instead, it cuts west above Three Forks continues south—crossing the Snake River Plain and skirting the west side of the Colorado Plateau before cutting west again to enter California. Although most of this mountain-building has since been obliterated by additional orogeny and volcanic activity, most of it still exists in northwestern Montana.[17] The Rocky Mountain Front in this area represents some of the highest changes of elevation within a short distance anywhere in North America. Much of this part of the front, including the Lewis Range and Livingston Range, have suffered heavy glaciation.[18]

According to a definition used by the Christian Science Monitor, the Rocky Mountain Front in Montana extends only about 100 miles (160 km) south of the state's northern border.[12] But professors Tony Prato and Dan Fagre define the front in Montana as being 50 miles (80 km) wide and 200 miles (320 km) long.[19]

Ranches cover much of the Rocky Mountain Front in Montana.[20] The spectacular scenery also led to the creation of a number of guest ranches in the area, and some of the state's best-known guest ranches are near Choteau and Augusta.[21]

The Rocky Mountain Front in Montana contains some of the last relatively untouched native prairies in the northern Great Plains.[22] The front forms the eastern boundary of what is called the "Crown of the Continent Ecosystem".[19] This area of Montana is prime habitat for wildlife, including the black bear, cougar, deer, elk, grizzly bear, lynx, moose, wolf, and wolverine. It is one of the few places in North America where grizzly bear habitat still extends onto the prairie.[23] Extensive numbers of prairie rattlesnake are also found there.[24]

Heavy coal, oil, and natural gas development along the Rocky Mountain Front in Montana began in the 1970s.[25] By the early 2000s, there were estimates of as much as 2.2 trillion cubic feet of natural gas below the front in Montana, although only 200 billion cubic feet was available on leasable land. By 2003, much of the Rocky Mountain Front in the state consisted of land owned by the U.S. federal government and managed by the United States Forest Service and the federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM).[12] By one count, BLM alone managed 13,000 acres (53 km2) of land on the Rocky Mountain Front in the state.[26] Beginning in 2001, petroleum exploration was banned for a six-year period on Forest Service land in the front. In the fall of 2002, BLM issued new regulations making it easier to engage in oil and gas production along the Montana front. Conservationists have actively worked to protect the region from energy exploration.[12]

Wyoming

Southwest Wyoming, where the borders of Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming come together, is another area where the Cordilleran foreland thrust-and-fold remains largely intact. (The other is northwest Montana, as noted above.)[17]

The Rocky Mountain Front in Wyoming is believed to have extensive oil and natural gas reserves. In the late 1970s, the U.S Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management attempted to open these lands to energy exploration. This led to extensive litigation and changes in federal land use regulations.[27]

Colorado

In Colorado, the Rocky Mountain Front extends from the west-northcentral part of the border with Wyoming south to the city Pueblo and the Arkansas River. Peaks within the front include Pikes Peak, Mount Evans, and Longs Peak. Just east of the Rocky Mountain Front is the Colorado Piedmont, and within the Piedmont is the most heavily urbanized part of the United States between Chicago and the West Coast. The only pass through the Rocky Mountains in the area is the Tennessee Pass.[28]

The Rocky Mountain Front forms the eastern boundary of a triangular area of volcanic activity centered on western Colorado.[29] Several sandstone horizons underlie the Colorado Rocky Mountain Front as well, and decline steeply to the east.[30]

In popular culture

"The Rocky Mountain Front" is the title of an essay by noted Montana author A. B. Guthrie, Jr. It first appeared in Montana, The Magazine of Western History in 1987.[31]

References

- Fitz-Diaz, Hudleston, and Tolson, p. 149; Welsch and Moore, p. 115; Kershaw, p. 25.

- Montana State Office, p. 46.

- Neudecker, Duvall, and Stutzman, p. 229.

- Wishart, p. xvi-xvii.

- Kudray and Cooper, p. 4. Accessed 2013-07-30.

- Brunner, et al., p. 147.

- Prothero, p. 190.

- Mathews and Monger, p. 287.

- Geological Survey of Canada, p. 50.

- Mayda, p. 401.

- In its natural state, natural gas is laced with hydrogen sulfide, which is lethal if inhaled in even tiny concentrations. This gas is called "sour gas" in the petroleum industry. Hydrogen sulfide can be removed from natural gas—a process called "sweetening"—by exposing it to dissolved soda ash.

- Herring, Hal. "In Montana, the Next Arctic Refuge Debate." Christian Science Monitor. October 30, 2003. Accessed 2013-07-30.

- Keyser and Klassen, p. 100.

- Molvar, Scenic Driving Alaska and the Yukon, p. 25.

- Heuer, p. 42.

- Baron, p. 28.

- DiPietro, p. 182.

- DiPietro, p. 182, 184.

- Prato and Fagre, p. 12.

- Prato and Fagre, p. 13.

- Jewell and McRae, p. 428.

- Prato and Fagre, p. 3.

- Prato and Fagre, p. 12-13.

- Long, p. 27.

- Baron, p. 6.

- Long, p. 32.

- Committee on Onshore Oil and Gas Leasing, p. 44.

- Hudson, p. 290-291.

- Steven, p. 75.

- Darton, p. 332.

- Benson, p. 282.

Bibliography

- Baron, Jill. Rocky Mountain Futures: An Ecological Perspective. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2002.

- Benson, Jackson J. Under the Big Sky: A Biography of A.B. Guthrie Jr. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

- Brunner, Ronald D.; Steelman, Toddi I.; Coe-Juell, Lindy; Cromley, Christina M.; Edwards, Christine M.; and Tucker, Donna W. Adaptive Governance: Integrating Science, Policy, and Decision Making. New York: Columbia University Press, 2005.

- Committee on Onshore Oil and Gas Leasing. Land Use Planning and Oil and Gas Leasing on Onshore Federal Lands. National Research Council. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press, 1989.

- Darton, Nelson Horatio. Preliminary Report on the Geology and Underground Water Resources of the Central Great Plains. Professional Paper No. 32. U.S. Geological Survey. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1905.

- DiPietro, Joseph A. Landscape Evolution in the United States: An Introduction to the Geography, Geology, and Natural History. Burlington, Mass.: Elsevier, 2013.

- Fitz-Diaz, Elisa; Hudleston, Peter; and Tolson, Gustavo. "Comparison of Tectonic Styles in the Mexican and Canadian Rocky Mountain Fold-Thrust Belt." In Kinematic Evolution and Structural Styles of Fold- and Thrust Belts. Josep Poblet and Richard J. Lisle, eds. London: Geological Society, 2010.

- Heuer, Karsten. Walking the Big Wild: From Yellowstone to the Yukon on the Grizzly Bears' Trail. Seattle, Wash.: Mountaineers Books, 2004.

- Hudson, John C. Across This Land: A Regional Geography of the United States and Canada. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

- Jewell, Judy and McRae, Bill. Moon Montana. Berkeley, Calif.: Avalon Travel, 2012.

- Kershaw, Robert. Exploring the Castle: Discovering the Backbone of the World in Southern Alberta. Surrey, B.C.: Rocky Mountain Books, 2008.

- Keyser, James D. and Klassen, Michael A. Plains Indian Rock Art. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001.

- Kudray, Gregory M. and Cooper, Steven V. "Montana's Rocky Mountain Front: Vegetation Map and Type Descriptions. Report to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service." Helena, Mont.: Montana Natural Heritage Program, 2006.

- Long, Ben. "The Crown of the Continent Ecosystem: Describing a Treasured Landscape." In Sustaining Rocky Mountain Landscapes: Science, Policy, and Management for the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem. Tony Prato and Dan Fagre, eds. New York: Routledge, 2013.

- Mathews, William Henry and Monger, J.W.H. Roadside Geology of Southern British Columbia. Missoula, Mont.: Mountain Press Publishing Co., 2005.

- Mayda, Chris. A Regional Geography of the United States and Canada: Toward a Sustainable Future. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2013.

- Molvar, Erik. Scenic Driving Alaska and the Yukon. Guilford, Conn.: Insiders' Guide, 2005.

- Montana State Office. Resource Management Plan: Environmental Impact Statement for the Headwaters Resource Area, Butte District, Montana. Bureau of Land Management. U.S. Department of the Interior. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Land Management, November 1983.

- Neudecker, Gregory A.; Duvall, Alison L.; Stutzman, James W. "Community-Based Landscape Conservation: A Roadmap for the Future." In Energy Development and Wildlife Conservation in Western North America. David E. Naugle, ed. Washington, D.C.: Island Press, 2011.

- Prato, Tony and Fagre, Dan. "The Crown of the Continent: Striving for Ecosystem Sustainability." In Sustaining Rocky Mountain Landscapes: Science, Policy, and Management for the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem. Tony Prato and Dan Fagre, eds. New York: Routledge, 2013.

- Prothero, Donald R. Catastrophes!: Earthquakes, Tsunamis, Tornadoes, and Other Earth-Shattering Disasters. Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011.

- Steven, Thomas A. "Middle Tertiary Volcanic Field in the Southern Rocky Mountains." In Cenozoic History of the Southern Rocky Mountains: Papers Derived From a Symposium Presented at the Rocky Mountain Section Meeting of The Geological Society of America, Boulder, Colorado, 1973. Bruce Franklin Curtis, ed. Boulder, Colo.: Geological Society of America, 1975.

- Welsch, Jeff and Moore, Sherry. Backroads and Byways of Montana: Drives, Day Trips and Weekend Excursions. Woodstock, Vt.: The Countryman Press, 2011.

- Wishart, David J. "The Great Plains Region." In Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. David J. Wishart, ed. Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 2004.