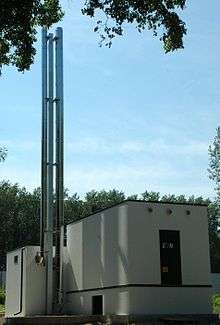

Biomass heating system

Biomass heating systems generate heat from biomass.

The systems fall under the categories of:

- direct combustion,

- gasification,

- combined heat and power (CHP),

- anaerobic digestion,

- aerobic digestion.

Benefits of biomass heating

The use of biomass in heating systems is beneficial because it uses agricultural, forest, urban and industrial residues and waste to produce heat and/or electricity with less effect on the environment than fossil fuels.[1] This type of energy production has a limited long-term effect on the environment because the carbon in biomass is part of the natural carbon cycle; while the carbon in fossil fuels is not, and permanently adds carbon to the environment when burned for fuel (carbon footprint).[2] Historically, before the use of fossil fuels in significant quantities, biomass in the form of wood fuel provided most of humanity's heating.

Forest Health

Because forest based biomass is typically derived from wood that has lower commercial value, forest biomass is typically harvested as a byproduct of other timber harvest operations. Biomass heating provides markets for lower value wood, which enables healthy and profitable forest management. In New England as of 2017, one of the greatest threats to forest health is conversion from forest to agriculture and development. Harvard Forest scientists reported in 2017, that 65 acres of forest were being lost per day by conversion. By providing markets for low grade wood, the value of forests is enhanced, which makes conversion to housing or agriculture less likely.[3]

Drawbacks of biomass heating

On a large scale, the use of agricultural biomass removes agricultural land from food production, reduces the carbon sequestration capacity of forests that are not managed sustainably, and extracts nutrients from the soil. Combustion of biomass creates air pollutants and adds significant quantities of carbon to the atmosphere that may not be returned to the soil for many decades.[4] The time delay between when biomass is burned and the time when carbon is pulled from the atmosphere as a plant or tree grows to replace it is known as carbon debt. The concept of carbon debt is subject to debate. Actual carbon impacts may be subject to philosophy, scale of harvest, land type, biomass type (grass, maize, new wood, waste wood, algae, for example), soil type, and other factors.[5]

Using biomass as a fuel produces air pollution in the form of carbon monoxide, NOx (nitrogen oxides), VOCs (volatile organic compounds), particulates and other pollutants, in some cases at levels above those from traditional fuel sources such as coal or natural gas.[6][7] Black carbon – a pollutant created by incomplete combustion of fossil fuels, biofuels, and biomass – is possibly the second largest contributor to global warming.[8] In 2009 a Swedish study of the giant brown haze that periodically covers large areas in South Asia determined that it had been principally produced by biomass burning, and to a lesser extent by fossil-fuel burning.[9] Researchers measured a significant concentration of 14C, which is associated with recent plant life rather than with fossil fuels.[10] Modern biomass burning appliances dramatically reduce harmful emissions with advanced technology such as oxygen trim systems.[11]

On combustion, the carbon from biomass is released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide (CO2). The amount of carbon stored in dry wood is approximately 50% by weight.[12] When from agricultural sources, plant matter used as a fuel can be replaced by planting for new growth. When the biomass is from forests, the time to recapture the carbon stored is generally longer, and the carbon storage capacity of the forest may be reduced overall if destructive forestry techniques are employed.[13][14][15][16]

The forest biomass-is-carbon-neutral proposal put forward in the early 1990s has been superseded by more recent science that recognizes that mature, intact forests sequester carbon more effectively than cut-over areas. When a tree’s carbon is released into the atmosphere in a single pulse, it contributes to climate change much more than woodland timber rotting slowly over decades.[17] Some studies indicate that "even after 50 years the forest has not recovered to its initial carbon storage" and "the optimal strategy is likely to be protection of the standing forest".[18] Other studies show that carbon storage is dependent upon the forest and the use of the harvested biomass. Forests are often managed for multiple aged trees with more frequent, smaller harvests of mature trees. These forests interact with carbon differently than mature forests that are clear-cut. Also, the more efficient the conversion of wood to energy, the less wood that is used and shorter the carbon cycle will be.[19]

Biomass heating in our world

The oil price increases since 2003 and consequent price increases for natural gas and coal have increased the value of biomass for heat generation. Forest renderings, agricultural waste, and crops grown specifically for energy production become competitive as the prices of energy dense fossil fuels rise. Efforts to develop this potential may have the effect of regenerating mismanaged croplands and be a cog in the wheel of a decentralized, multi-dimensional renewable energy industry. Efforts to promote and advance these methods became common throughout the European Union through the 2000s. In other areas of the world, inefficient and polluting means to generate heat from biomass coupled with poor forest practices have significantly added to environmental degradation.

Buffer tanks

Buffer tanks store the hot water the biomass appliance generates and circulates it around the heating system.[20] Sometimes referred to as 'thermal stores', they are crucial for the efficient operation of all biomass boilers where the system loading fluctuates rapidly, or the volume of water in the complete hydraulic system is relatively small. Using a suitably sized buffer vessel prevents rapid cycling of the boiler when the loading is below the minimum boiler output. Rapid cycling of the boiler causes a large increase in harmful emissions such as Carbon monoxide, dust, and NOx, greatly reduces boiler efficiency and increases electrical consumption of the unit. In addition, service and maintenance requirements will be increased as parts are stressed by rapid heating and cooling cycles. Although most boilers claim to be able to turn down to 30% of nominal output, in the real world this is often not achievable due to differences in the fuel from the 'ideal' or test fuel. A suitably sized buffer tank should therefore be considered where the loading of the boiler drops below 50% of the nominal output – in other words unless the biomass component is purely base load, the system should include a buffer tank. In any case where the secondary system does not contain sufficient water for safe removal of residual heat from the biomass boiler irrespective of the loading conditions, the system must include a suitably sized buffer tank. The residual heat from a biomass unit varies greatly depending on the boiler design and the thermal mass of the combustion chamber. Light weight, fast response boilers require only 10L/kW, while industrial wet wood units with very high thermal mass require 40L/kW.[21]

Types of biomass heating systems

The use of Biomass in heating systems has a use in many different types of buildings, and all have different uses. There are four main types of heating systems that use biomass to heat a boiler. The types are Fully Automated, Semi-Automated, Pellet-Fired, and Combined Heat and Power.

Fully automated

In fully automated systems chipped or ground up waste wood is brought to the site by delivery trucks and dropped into a holding tank. A system of conveyors then transports the wood from the holding tank to the boiler at a certain managed rate. This rate is managed by computer controls and a laser that measures the load of fuel the conveyor is bringing in. The system automatically goes on and off to maintain the pressure and temperature within the boiler. Fully automated systems offer a great deal of ease in their operation because they only require the operator of the system to control the computer, and not the transport of wood while offering comprehensive and cost effective solutions to complex industrial challenges.[22][23]

Semi-automated or "surge bin"

Semi-automated or "Surge Bin" systems are very similar to fully automated systems except they require more manpower to keep operational. They have smaller holding tanks, and a much simpler conveyor systems which will require personnel to maintain the systems operation. The reasoning for the changes from the fully automated system is the efficiency of the system. The heat created by the combustor can be used to directly heat the air or it can be used to heat water in a boiler system which acts as the medium by which the heat is delivered.[24] Wood fire fueled boilers are most efficient when they are running at their highest capacity, and the heat required most days of the year will not be the peak heat requirement for the year. Considering that the system will only need to run at a high capacity a few days of the year, it is made to meet the requirements for the majority of the year to maintain its high efficiency.[23]

Pellet-fired

The third main type of biomass heating systems are pellet-fired systems. Pellets are a processed form of wood, which make them more expensive. Although they are more expensive, they are much more condensed and uniform, and therefore are more efficient. Further, it is relatively easy to automatically feed pellets to boilers. In these systems, the pellets are stored in a grain-type storage silo, and gravity is used to move them to the boiler. The storage requirements are much smaller for pellet-fired systems because of their condensed nature, which also helps cut down costs. these systems are used for a wide variety of facilities, but they are most efficient and cost effective for places where space for storage and conveyor systems is limited, and where the pellets are made fairly close to the facility.[23]

Agricultural pellet systems

One subcategory of pellet systems are boilers or burners capable of burning pellet with higher ash rate (paper pellets, hay pellets, straw pellets). One of this kind is PETROJET pellet burner with rotating cylindrical burning chamber.[25] In terms of efficiencies advanced pellet boilers can exceed other forms of biomass because of the more stable fuel charataristics. Advanced pellet boilers can even work in condensing mode and cool down combustion gases to 30-40 °C, instead of 120 °C before sent into the flue.[26]

Combined heat and power

Combined heat and power systems are very useful systems in which wood waste, such as wood chips, is used to generate power, and heat is created as a byproduct of the power generation system. They have a very high cost because of the high pressure operation. Because of this high pressure operation, the need for a highly trained operator is mandatory, and will raise the cost of operation. Another drawback is that while they produce electricity they will produce heat, and if producing heat is not desirable for certain parts of the year, the addition of a cooling tower is necessary, and will also raise the cost.

There are certain situations where CHP is a good option. Wood product manufacturers would use a combined heat and power system because they have a large supply of waste wood, and a need for both heat and power. Other places where these systems would be optimal are hospitals and prisons, which need energy, and heat for hot water. These systems are sized so that they will produce enough heat to match the average heat load so that no additional heat is needed, and a cooling tower is not needed.[23]

See also

References

- Vallios, I; Tsoutsos, T; Papadakis, G (2009). "Design of Biomass District Heating". Biomass & Bioenergy. 33 (4): 659–678.

- "Wood Fuelled Heating". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- "Wildlands & Woodlands | Harvard Forest". harvardforest.fas.harvard.edu. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- "Opinion of the EEA Scientific Committee on Greenhouse Gas Accounting in Relation to Bioenergy".

- Malmsheimer, Robert (October 2016). "Biomass Boilers, Greenhouse Gases, and Climate Change: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Carbon Emissions from your Biomass Boiler but were Afraid to Ask!" (PDF).

- "George Lopez visits the Fox Theatre". Michigan Messenger. 22 February 1999. Archived from the original on 5 February 2010.

- "Household air pollution from coal and biomass fuels in China: measurements, health impacts, and interventions". Environ. Health Perspect. 115 (6): 848–55. June 2007. doi:10.1289/ehp.9479. PMC 1892127. PMID 17589590.

- 2009 State of the World, Into a Warming World,Worldwatch Institute, 56–57, ISBN 978-0-393-33418-0

- Science, 2009, 323, 495

- Biomass burning leads to Asian brown cloud, Chemical & Engineering News, 87, 4, 31

- Nussbaumer, Thomas (April 2008). "Biomass Combustion in Europe Overview On Technologies and Regulations" (PDF).

- "Forest volume-to-biomass models and estimates of mass for live and standing dead trees of U.S. forests" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2007.

- Prasad, Ram. "SUSTAINABLE FOREST MANAGEMENT FOR DRY FORESTS OF SOUTH ASIA". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "Treetrouble: Testimonies on the Negative Impact of Large-scale Tree Plantations prepared for the sixth Conference of the Parties of the Framework Convention on Climate Change". Friends of the Earth International. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Laiho, Raija; Sanchez, Felipe; Tiarks, Allan; Dougherty, Phillip M.; Trettin, Carl C. "Impacts of intensive forestry on early rotation trends in site carbon pools in the southeastern US". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- "THE FINANCIAL AND INSTITUTIONAL FEASIBILITY OF SUSTAINABLE FOREST MANAGEMENT". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 11 August 2010.

- Mary S. Booth. "Biomass Briefing, October 2009" (PDF). massenvironmentalenergy.org. Massachusetts Environmental Energy Alliance. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2010.

- Edmunds, Joe; Richard Richets; Marshall Wise, "Future Fossil Fuel Carbon Emissions without Policy Intervention: A Review". In T. M. L. Wigley, David Steven Schimel, The carbon cycle. Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp.171–189

- "Past Project: Woody Biomass Energy". Manomet. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- "Buffer Tanks and Hot Water Storage - Treco". www.treco.co.uk. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- "Buffer tanks".

- "Automation: Combustion Control & Burner Management Systems". Sigma Thermal. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- "Types of Biomass Heating Systems".

- "Biomass System Design - Selected Eco Energy". Selected Eco Energy. Retrieved 18 October 2016.

- "Great results from Swedish testing laboratory | Petrojet Trade s.r.o". Horakypetrojet.cz. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- "Okofen condesing pellet boiler".