Pickled cucumber

A pickled cucumber (commonly known as a pickle in the United States and Canada, and a gherkin in Britain, Ireland, Australia, South Africa and New Zealand) is a cucumber that has been pickled in a brine, vinegar, or other solution and left to ferment for a period of time, by either immersing the cucumbers in an acidic solution or through souring by lacto-fermentation. Pickled cucumbers are often part of mixed pickles.

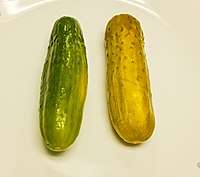

A deli pickle | |

| Alternative names | Pickle, gherkin |

|---|---|

| Course | Hors d'oeuvre |

| Main ingredients | Cucumber, brine or vinegar or other solution |

| Variations | Cornichon, gherkin |

Historical origins

It is often claimed that pickled cucumbers were first developed for workers building the Great Wall of China,[1] though another hypothesis is that they were first made in the Tigris Valley of Mesopotamia, using cucumbers brought originally from India.[2]

Types

Brined pickles

Brined pickles are prepared using the traditional process of natural fermentation in a brine which makes them grow sour. The brine concentration can vary between 20 and more than 40 grams of salt per litre of water (3.2–6.4 oz/imp gal or 2.7–5.3 oz/US gal). There is no vinegar used in the brine of naturally fermented pickled cucumbers.

The fermentation process is dependent on the Lactobacillus bacteria that naturally occur on the skin of a growing cucumber. These may be removed during commercial harvesting and packing processes. Bacteria cultures can be reintroduced to the vegetables by adding already fermented foods such as yogurt or other fermented milk products, pieces of sourdough bread, or pickled vegetables such as sauerkraut.

Typically, small cucumbers are placed in a glass or ceramic vessel or a wooden barrel, together with a variety of spices. Among those traditionally used in many recipes are garlic, horseradish, whole dill stems with umbels and green seeds, white mustard seeds, grape, oak, cherry, blackcurrant and bay laurel leaves, dried allspice fruits, and—most importantly—salt. The container is then filled with cooled, boiled water and kept under a non-airtight cover (often cloth tied on with string or a rubber band) for several weeks, depending on taste and external temperature. Traditionally stones, also sterilized by boiling, are placed on top of the cucumbers to keep them under the water. The more salt is added the more sour the cucumbers become.

Since they are produced without vinegar, a film of bacteria forms on the top, but this does not indicate they have spoiled, and the film is simply removed. They do not, however, keep as long as cucumbers pickled with vinegar, and usually must be refrigerated. Some commercial manufacturers add vinegar as a preservative.

Bread-and-butter

Bread-and-butter pickles are a marinated pickle produced with sliced cucumbers in a solution of vinegar, sugar, and spices which may be processed either by canning or simply chilled as refrigerator pickles. The origin of the name and the spread of their popularity in the United States is attributed to Omar and Cora Fanning, a pair of Illinois cucumber farmers who started selling sweet and sour pickles in the 1920s and filed for the trademark "Fanning's Bread and Butter Pickles" in 1923 (though the recipe and similar ones are probably much older).[3] The story attached to the name is that the Fannings survived rough years by making the pickles with their surplus of undersized cucumbers and bartering them with their grocer for staples such as bread and butter.[4]

Gherkin

Gherkins, or baby pickles, are small cucumbers, typically those 1 inch (2.5 cm) to 5 inches (13 cm) in length, often with bumpy skin, which are typically used for pickling.[5][6][7] The word gherkin comes from early modern Dutch, gurken or augurken for "small pickled cucumber".[8]

Cornichons are tart French pickles made from gherkins pickled in vinegar and tarragon. They traditionally accompany pâtés and cold cuts.[9][10] Sweet gherkins, which contain sugar in the pickling brine, are also a popular variety.

The term "gherkin" is also used in the name West Indian gherkin for Cucumis anguria, a closely related species.[11][12][13] West Indian gherkins are also sometimes used as pickles.[14]

Kosher dill

A "kosher" dill pickle is not necessarily kosher in the sense that it has been prepared in accordance with Jewish dietary law. Rather, it is a pickle made in the traditional manner of Jewish New York City pickle makers, with generous addition of garlic and dill to a natural salt brine.[15][16][17]

In New York terminology, a "full-sour" kosher dill is one that has fully fermented, while a "half-sour", given a shorter stay in the brine, is still crisp and bright green.[18] Elsewhere, these pickles may sometimes be termed "old" and "new" dills.

Dill pickles (not necessarily described as "kosher") have been served in New York City since at least 1899.[19]

Hungarian

In Hungary, while regular vinegar-pickled cucumbers (Hungarian: savanyú uborka) are made during most of the year, during the summer kovászos uborka ("leavened pickles") are made without the use of vinegar. Cucumbers are placed in a glass vessel along with spices (usually dill and garlic), water and salt. Additionally, a slice or two of bread are placed at the top and bottom of the solution, and the container is left to sit in the sun for a few days so the yeast in the bread can help cause a fermentation process.[20]

Polish and German

The Polish- or German-style pickled cucumber (Polish: ogórek kiszony/kwaszony; German: Salzgurken), was developed in the northern parts of central and eastern Europe. It has been exported worldwide and is found in the cuisines of many countries, including the United States, where it was introduced by immigrants. It is sour, similar to the kosher dill, but tends to be seasoned differently.

Traditionally, pickles were preserved in wooden barrels, but are now sold in glass jars. A cucumber only pickled for a few days is different in taste (less sour) than one pickled for a longer time and is called ogórek małosolny, which literally means "low-salt cucumber." This distinction is similar to the one between half- and full-sour types of kosher dills (see above).

Another kind of pickled cucumber popular in Poland is ogórek konserwowy ("preserved cucumber") which is rather sweet and vinegary in taste, due to different composition of the preserving solution.

Lime

Lime pickles are soaked in pickling lime (not to be confused with the citrus fruit) rather than in a salt brine.[21] This is done more to enhance texture (by making them crisper) rather than as a preservative. The lime is then rinsed off the pickles. Vinegar and sugar are often added after the 24-hour soak in lime, along with pickling spices.

Nutrition

Like pickled vegetables such as sauerkraut, sour pickled cucumbers (technically a fruit) are low in calories. They also contain a moderate amount of vitamin K, specifically in the form of K1. 30-gram sour pickled cucumber offers 12–16 µg, or approximately 15–20%, of the Recommended Daily Allowance of vitamin K. It also offers 3 kilocalories (13 kJ), most of which come from carbohydrate.[23] However, most sour pickled cucumbers are also high in sodium; one pickled cucumber can contain 350–500 mg, or 15–20% of the American recommended daily limit of 2400 mg.[24]

Sweet pickled cucumbers, including bread-and-butter pickles, are higher in calories due to their sugar content; a similar 30-gram portion may contain 20 to 30 kilocalories (84 to 126 kJ). Sweet pickled cucumbers also tend to contain significantly less sodium than sour pickles.[25]

Pickles are being researched for their ability to act as vegetables with a high probiotic content. Probiotics are typically associated with dairy products, but lactobacilli species such as L. plantarum and L. brevis have been shown to add to the nutritional value of pickles.[26]

Serving

In the United States, pickles are often served as a side dish accompanying meals. This often takes the form of a "pickle spear", which is a pickled cucumber cut length-wise into quarters or sixths. Pickles may be used as a condiment on a hamburger or other sandwich (usually in slice form), or on a sausage or hot dog in chopped form as pickle relish.

Soured cucumbers are commonly used in a variety of dishes—for example, pickle-stuffed meatloaf,[27] potato salad or chicken salad—or consumed alone as an appetizer.

Pickles are sometimes served alone as festival foods, often on a stick. This is also done in Japan, where it is referred to as "stick pickle" (一本漬, ippon-tsuke).

Dill pickles can be fried, typically deep-fried with a breading or batter surrounding the spear or slice. This is a popular dish in the southern US, and a rising trend elsewhere in the US.[28]

In Russia and Ukraine, pickles are used in rassolnik: a traditional soup made from pickled cucumbers, pearl barley, pork or beef kidneys, and various herbs. The dish is known to have existed as far back as the 15th century, when it was called kalya.

In southern England, large gherkins pickled in vinegar are served as an accompaniment to fish and chips, and are sold from big jars on the counter at a fish and chip shop, along with pickled onions.[29] In the Cockney dialect of London, this type of gherkin is called a "wally".[30]

Etymology

The term pickle is derived from the Dutch word pekel, meaning brine.[31] In the United States and Canada, the word pickle alone refers to a pickled cucumber (other types of pickles will be described as "pickled onion", "pickled beets", etc.). In the UK pickle generally refers to ploughman's pickle made from various vegetables, such as Branston pickle, traditionally served with a ploughman's lunch.

Gallery

Fresh pickling cucumbers for sale in Kraków

Fresh pickling cucumbers for sale in Kraków Cucumbers in salted water with dill (Poland)

Cucumbers in salted water with dill (Poland) German pickles called Spreewald gherkins

German pickles called Spreewald gherkins Cover for 1906 U.S. ragtime piece "Dill Pickles"

Cover for 1906 U.S. ragtime piece "Dill Pickles"- Large gherkins and pickled onions in a fish and chip shop in London

See also

- List of pickled foods – List of links to Wikipedia articles on pickled foods

- Pickle soup

- Glowing pickle demonstration – Ions within the pickle emit light as a result of atomic electron transitions

References

- Brown, Amy Christine (2018-01-01). Understanding Food: Principles and Preparation. Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781337557566.

- "History in a Jar: Story of Pickles | The History Kitchen | PBS Food". PBS Food. 2014-09-03. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- United States Patent and Trademark Office. "Trademark Electronic Search System (TESS)". tmsearch.uspto.gov. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- Oulton, Randal W. "Bread and Butter Pickles". CooksInfo.com. Retrieved 22 January 2015.

- "Gherkins". Venlo, Netherlands: Zon. 2017. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- "Cucumbers" (PDF). University of California-Davis: Western Institute for Food Safety and Security, US Department of Agriculture. May 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- "Cucumbers and gherkins". Agricultural and Processed Food Products Export Development Authority, Government of India. 2015. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- "Word origin and history for gherkin". Dictionary.com. 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- Cornichons. CooksInfo.com. Published 8 June 2007. Updated 8 June 2007. Web. Retrieved 26 October 2012 from http://www.cooksinfo.com/cornichons

- "What's The Deal With Cornichons?". The Kitchn. 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- "West Indian gherkin, Cucumis anguria L." Plants for a Future. 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- Kathryn Hawkins (2007). Allotment Cookbook. New Holland Publishers. p. 42.

- Martin Anderson, Texas AgriLife Extension Service. "Cucumber - Archives - Aggie Horticulture". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Cucumis anguria". EcoCrop. FAO. 1993–2007. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- "Untitled Document". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Zeldes, Leah A. (20 July 2010). "Origins of neon relish and other Chicago hot dog conundrums". Dining Chicago. Chicago's Restaurant & Entertainment Guide, Inc. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

'Kosher-style' means the pickles are naturally fermented in a salt brine....

- "Judaism 101: Kashrut: Jewish Dietary Laws". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Dill Pickles". CooksInfo.com. 5 March 2010. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- "DINNER [held by] HAAN'S [at] "PARK ROW BUILDING, [NY]" (REST;)". NYPL Digital Collections. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Kovászos Uborka". Chew.hu. All Hungary Media Group. 22 July 2009. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- "RecipeSource: Lime Pickles". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Edge, John T. (9 May 2007). "A Sweet So Sour: Kool-Aid Dills". The New York Times.

- USDA SR22 (http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/search/ Archived 2015-03-03 at the Wayback Machine) -- "Pickles, cucumber, sour", (30 g): 0.10 g protein; 0.68 g carbohydrates; 0.06 g fat

- "Nutrition Facts". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Nutrition Facts". Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Tokatli, Mehmet; Gulgor, Goksen; Elmaci, Simel Bagder; Isleyen, Nurdan Arslankoz; Ozcelik, Filiz (17 May 2015). "In Vitro Properties of Potential Probiotic Indigenous Lactic Acid Bacteria Originating from Traditional Pickles". BioMed Research International. 2015: 1. doi:10.1155/2015/315819. PMC 4460932. PMID 26101771.

- Pickled Stuffed Meatloaf Archived 2007-10-23 at the Wayback Machine at ilovepickles.org

- Zeldes, Leah A. (2 December 2009). "Eat this! Southern-fried dill pickles, a rising trend". Dining Chicago. Chicago's Restaurant & Entertainment Guide, Inc. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- Le Vay, Benedict (2005). Eccentric Britain: The Bradt Guide to Britain's Follies and Foibles. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 261. ISBN 978-1841620114.

- Dale, Rodney (2000). The Wordsworth Dictionary of Culinary & Menu Terms. Wordsworth Editions Ltd. p. 460. ISBN 978-1840223002.

- Online Etymology Dictionary. "Pickle". Douglas Harper. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

Sources

- Battcock, Mike; Azam-Ali, Sue (1998). Fermented Fruits and Vegetables: A Global Perspective. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 92-5-104226-8. OCLC 41178885.

- Cross, Nanna (2006). "Pickle Manufacturing in the United States: Quality Assurance and Establishment Inspection". In Hui, Yiu H. (ed.). Handbook of Food Science, Technology, and Engineering. vol. 2. Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 70/1–70/12. ISBN 978-0-8493-9848-3.

- Elkner, Krystyna (2016). "Jakość ogórków kiszonych" [Quality of pickled cucumbers]. Hasło Ogrodnicze (in Polish). Kraków: Plantpress (8).

- Fleming, H.P.; McFeeters, R.F.; Breidt, F. (2001). "Fermented and Acidified Vegetables". In Downes, Pouch; Ito, Keith (eds.). Compendium of Methods for the Microbiological Examination of Foods (PDF). Washington, DC: American Public Health Association. pp. 521–532.

- Frazier, William C.; Westoff, Dennis C.; Vanitha, K.N. (1971). Food Microbiology. McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-93-39-20322-1.

- Marks, Gil (2008). Olive Trees and Honey: A Treasury of Vegetarian Recipes from Jewish Communities Around the World. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7645-4413-2.

- Osińska, Jadwiga (1950). Ogórki kiszone [Pickled cucumbers] (in Polish). Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwa Techniczne.

- Swain, Manas Ranjan; Anandharaj, Marimuthu; Ray, Ramesh Chandra; Parveen Rani, Rizwana (2014). "Fermented Fruits and Vegetables of Asia: A Potential Source of Probiotics". Biotechnology Research International. Hindawi Publishing Corporation. 2014: 250424. doi:10.1155/2014/250424. ISSN 2090-3146. PMC 4058509. PMID 25343046.

- "The Pickle Wing". New York: The NY Food Museum.

- Wacher, Carmen; Díaz-Ruiz, Gloria; Tamang, Jyoti Prakash (2010). "Fermented Vegetable Products". In Tamang, J.P.; Kailasapathy, Kasipathy (eds.). Fermented Foods and Beverages of the World. Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 151–190. ISBN 978-1-4200-9496-1.

External links