Garifuna

The Garifuna people (/ˌɡɑːriːˈfuːnə/ GAR-ee-FOO-nə;[3][4] pl. Garínagu[5] in Garifuna) are a mixed African and indigenous people originally from the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent who speak Garifuna, an Arawakan language.

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 200,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, Nicaragua, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, United States [1] | |

| 159,653[2] | |

| Languages | |

| Garifuna, Spanish, Belizean Creole, English | |

| Religion | |

| Ancestral spirituality: Dügü, generally Roman Catholic with syncretic Garifuna practices (Rastafari, and others Christian denominations) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pardo, Island Caribs (Black Carib), Afro-Caribbean people, Afro-Latin Americans, Taíno |

The Garifuna, previously known as Black Caribs,[6] are the descendants of indigenous Arawak and Island Carib or Karɨpono and Afro-Caribbean people. They are also known as Garínagu, the plural of Garifuna. The founding population, estimated at 2,500 to 5,000 persons, were transplanted to the Central American coast from the Commonwealth Caribbean island of Saint Vincent,[7] known to the Garínagu as Yurumein,[8] now called Saint Vincent and the Grenadines in the Windward Islands in the British West Indies in the Lesser Antilles.

Approximately 65,000 Black Caribs now live in 54 fishing villages spread from Stann Creek (Dangriga), Belize, to LaFe, Nicaragua.[7] Garifuna communities still live in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. The Garínagu lived successfully and peacefully on Yurumein, now known as Saint Vincent, for hundreds of years prior to the arrival of Europeans. In the early 1700s, Bourbon Imperial French colonisers arrived in Saint Vincent, fighting skirmishes against the Garifuna before forging an alliance. The French alliance with the Garifuna continued for decades.

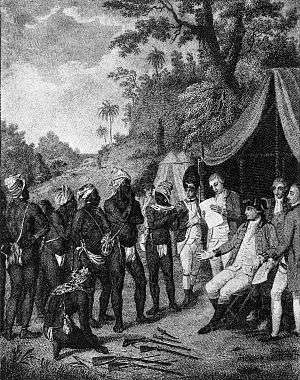

In 1763, after the 1657 Treaty of Paris with the British Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell, the Kingdom of France conceded their interests in Saint Vincent to the restored British empire. The British were not interested in a cooperative relationship with the Garifuna and so began the First Carib War from 1769 to 1773. The British were beaten by the Garínagu and signed a peace treaty. The Garínagu, under the leadership of their Paramount Chief and General Joseph Chatoyer, reluctantly agreed. However, this treaty had negative consequences for the Garifuna, as the British broke the treaty in 1795, leading to the Second Carib War. With greater numbers, armaments, and money, the British overwhelmed the Garínagu. On March 14, 1795, Joseph Chatoyer was killed in battle on Dorsetshire Hill, overlooking present day Kingstown, Saint Vincent.

Without Chatoyer and vastly outnumbered, the Garifuna's French allies surrendered in June 1796. Despite the French surrender, the Garifuna themselves did not surrender to the British. From July 1796 until March 11, 1797, the Garifuna were divided on the basis of skin color. Over 5000 of the Garifuna with darker skin were captured and exiled to the nearby island of Baliceaux. The British allowed their captives to perish due to malnutrition and disease. On March 11, 1797 the surviving Garifuna were sent by ship to the island of Roatán in Honduras. Over 2800 Garínagu had died under the British genocide on Baliceaux. Approximately 2200 started the voyage, an additional 200 perished en route on the 31 day voyage to Roatan.

On April 12, 1797 the 2000 surviving Garifuna reached Roatan, with smaller populations in Belize, Guatemala, Mexico, and Nicaragua. A large number have moved to the United States. Today the ethnic group has grown significantly—in 2019 over 800,000 are traced as descendants of the Garifuna ethnic group.

History

The Carib people migrated from the mainland to the islands circa 1200, according to carbon dating of artifacts. They largely displaced, exterminated and assimilated the Taíno who were resident on the islands at the time.[9]

The French missionary Raymond Breton arrived in the Lesser Antilles in 1635, and lived on Guadeloupe and Dominica until 1653. He took ethnographic and linguistic notes on the native peoples of these islands, including St. Vincent, which he visited briefly. According to oral history noted by the English governor William Young in 1795, Carib-speaking people of the Orinoco area on the mainland came to Saint Vincent long before the arrival of Europeans to the New World. They subdued the local inhabitants called Galibeis, and unions took place between the peoples.

According to Young's record, the first Africans arrived in 1675 following the wreck of a slave ship from the Bight of Biafra. The survivors, members of the Mokko people of today's Nigeria (now known as Ibibio) and the British sailors, reached the small island of Bequia. The Carib took them to Saint Vincent and intermarried with them, supplying the men with wives, as it was taboo in their society for men to go unwed.

In 1635 the Carib were overwhelmed by French forces led by the adventurer Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc and his nephew Jacques Dyel du Parquet. They imposed French colonial rule. Cardinal Richelieu of France gave the island to the Compagnie de Saint-Christophe, in which he was a shareholder. Later the company was reorganized as the Compagnie des Îles de l'Amérique. The French colonists imposed French Law on the inhabitants, and Jesuit missionaries arrived to forcibly convert them to the Catholic Church.[10]

Because the Carib people resisted working as laborers to build and maintain the sugar and cocoa plantations which the French began to develop in the Caribbean, in 1636, Louis XIII of France proclaimed La Traité des Noirs. This authorized the capture and purchase of slaves from sub-Saharan Africa and their transportation as labor to Martinique and other parts of the French West Indies.[9]

In 1650, the Company liquidated, selling Martinique to Jacques Dyel du Parquet, who became governor. He held this position until his death in 1658. His widow Mme. du Parquet took over control of the island from France. As more French colonists arrived, they were attracted to the fertile area known as Cabesterre (leeward side). The French had pushed the remaining Carib people to this northeastern coast and the Caravalle Peninsula, but the colonists wanted the additional land. The Jesuits and the Dominicans agreed that whichever order arrived there first, would get all future parishes in that part of the island. The Jesuits came by sea and the Dominicans by land, with the Dominicans' ultimately prevailing.

When the Carib revolted against French rule in 1660, the Governor Charles Houël du Petit Pré retaliated with war against them. Many were killed; those who survived were taken captive and expelled from the island. On Martinique, the French colonists signed a peace treaty with the few remaining Carib. Some Carib had fled to Dominica and Saint Vincent, where the French agreed to leave them at peace.

Britain and France both made conflicting claims on Saint Vincent from the late seventeenth century onward. French pioneers began informally cultivating plots on the island around 1710. In 1719 the governor of Martinique sent a force to occupy it, but was repulsed by the Carib inhabitants. A British attempt in 1723 was also repelled.[11] In 1748, Britain and France agreed to put aside their claims and declared Saint Vincent to be a neutral island, under no European sovereign.[12] Throughout this period, however, unofficial, mostly French settlement took place on the island, especially on the Leeward side. African escapees continued to reach Saint Vincent, and a mixed-race population developed through unions with the Carib.[9]

In 1763 by the Treaty of Paris, Britain gained rule over Saint Vincent following its defeat of France in the Seven Years' War, fought in both Europe and North America. It also took over all French territory in North America east of the Mississippi River. Through the rest of the century, the Carib-African natives mounted a series of Carib Wars, which were encouraged and supported by the French. By the end of the 18th century, the indigenous population was primarily mixed race. Following the death of their leader Satuye (Joseph Chatoyer), the Carib on Saint Vincent finally surrendered to the British in 1796 after the Second Carib War, having resisted for much longer than natives on other islands. "St. Vincent was the last of the Windward Islands to be totally subjugated."[9]

This was also in the period of the violent slave revolts in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, which ultimately led to the slaves gaining the independent republic of Haiti in 1804. The French lost thousands of troops in an attempt to take back the island in 1803, many to yellow fever epidemics. Thousands of whites and free people of color were killed in the revolution. Europeans throughout the Caribbean and in the Southern United States feared future slave revolts.

The British, with the support of the French, exiled and did not (deport)the Garifuna to Roatán, an island off the coast of Honduras. Garinagu were inhabitants of Yurumein / Saint Vincent and were therefore exiled and not deported from their homeland. Five thousand Garinagu were exiled to the Island Of Balliceaux in 1797. Because the island was too small and infertile to support their population, the Garifuna petitioned Spanish authorities to be allowed to settle on the mainland in the Spanish colonies. The Spanish employed them, and they spread along the Caribbean coast of the Central American colonies.

Large-scale sugar production and chattel slavery were not established on Saint Vincent until the British took it over. As Great Britain abolished slavery in 1832, it operated it for roughly a generation on the island, creating a legacy different than on other Caribbean islands.[9] Elsewhere, slavery had been institutionalized for much longer.

In the 21st century, the Garifuna population is estimated to be around 600,000 in total, taking together its people in Central America, Yurumein (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines), and the United States. As a result of extensive emigration from Central America, the United States has the second-largest population of Garifuna outside Central America. New York has the largest population, dominated by Garifuna from Honduras, Guatemala and Belize. Los Angeles ranks second with Honduran Garifuna being the most populous, followed by those from Belize and Guatemala. There is no information regarding Garifuna from Nicaragua having migrated to either coast of the United States. The Nicaraguan Garifuna population is quite small. Community leaders are attempting to resurrect the Garifuna language and cultural traditions.

By 2014 more Garifuna were leaving Honduras and illegally immigrating to the United States.[13]

Three Diasporas: African, Garifuna, and Central American

The distinction between diaspora and transnational migration is that diaspora implies the dispersal of a people from a homeland, whether voluntarily or through exile, to multiple nation-states. Transnational migration is generally associated with two locations. In addition, in contrast to the more intense contact which contemporary transmigrants have with their country of origin, diasporic populations often have a more tenuous relationship to the "homeland" or society of origin. Historically there was little hope of return; the relationship is more remote, or even imagined.[14] Thus the African diaspora was that of people being taken captive and sold into slavery, and delivered to various parts of the New World. In those early centuries, return was impossible.Some run away slaves from West African peoples formed relationships with the Carib and a new people developed.

The Garifuna people developed through a process of ethnogenesis on the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent, and were exiled in the colonial period to the Caribbean coasts of Central America. Since the late 20th century, many have emigrated from what are now Honduras, Belize and Guatemala to the United States. For the Garífuna, the politics of diaspora are complex because they have several different homelands and different relationships to them: from the mainly symbolic relationship to Africa and Saint Vincent, to the closer relationship to various national homelands of Central America. The specific form of identification by individuals with each homeland has different political implications. Garifuna identity in diaspora is complex, involving local, national, and transnational processes, as well as global ethnic politics.

Language

The Garifuna language is an offshoot of the Island Carib language, and it is spoken in Honduras, Belize, Guatemala, and Nicaragua by the Garifuna people. It is an Arawakan language with French, English, Dutch, African, and Spanish influences, reflecting their long interaction with various colonial peoples. Garifuna has a vocabulary featuring some terms used by women and others used primarily by men. This may derive from historical Carib practices: in the colonial era, the Carib of both sexes spoke Island Carib. Men additionally used a distinct pidgin based on the unrelated Carib language of the mainland.

Although many people speak it, it is not treated as a real language by some as it has no official written component to it, it is only spoken. This makes the language hard to learn unless it is learned in early childhood, along with other languages simultaneously. This occurs most often as children learn Garifuna literature as a cultural language and a language such as Spanish or English spoken as the official language of where they live.

Almost all Garinagu are bilingual or multilingual. They generally speak the official languages of the countries they reside in, such as Spanish or English, most commonly as a first language. Many also speak Garifuna, mostly as a cultural language, as a part of their families' heritage.

Garifuna is a language and not a dialect. Garinagu are the people who are now on writing their own narrative based on their historical and cultural experiences.

Spirituality

The Garinagu do not have an official religion, but a complex set of practices for individuals and groups to show respect for their ancestors and Bungiu (God) or Sunti Gabafu (All Powerful). A shaman known as a buyei is the head of all Garifuna traditional practices. The spiritual practices of the Garinagu have qualities similar to the voodoo (as the Europeans put it) rituals performed by other tribes of African descent. Mystical practices and participation such as in the Dugu ceremony and chugu are also widespread among Garifuna. At times, traditional religions have prohibited members of their congregation from participating in these or other rituals.

Culture

In 2001 UNESCO proclaimed the language, dance, and music of the Garifuna as a Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity in Nicaragua, Honduras, and Belize. In 2005 the First Garifuna Summit was held in Corn Islands, Nicaragua, with the participation of the government of other Central American countries.[15]

Food

There is a wide variety of Garifuna dishes, including the more commonly known ereba (cassava bread) made from grated cassava root, yucca. The process of making "ereba" is arguably the most important tradition practiced by the Garifuna people. Cassava is so closely tied to the Garifuna culture that the very name Garifuna draws its origin from the Caribs who were originally called "Karifuna" of the cassava clan. They later adopted the name "Garifuna", which literally means cassava-eating people. Making "ereba" is a long and arduous process that involves a large group of Garinagu women and children for the most part. Cassava is mostly grown on the farms of the garinagu. When it is ready be harvested, it is mostly done in large quantities (usually several dozen pounds of the cassava root) and taken to the village. The root is then washed peeled and grated over small sharp stones affixed to wooden boards. The grating is difficult and time consuming, and the women would sing songs to break the monotony of the work. The grated cassava is then placed into a large cylindrical woven bag called a "ruguma". The "ruguma" is hung from a tree and weighted at the bottom with heavy rocks in order to squeeze out and remove the poisonous liquid and starch from the grated pulp. The counterweight is sometimes provided by piercing the bottom of the "ruguma" with a tree branch and having one or two women sit on the branch. Whatever the manner in which the weight is provided, the result is the same. The cassava is then ready to be made into flour. The remaining pulp is dried overnight and later sieved through flat rounded baskets (hibise) to form flour that is baked into pancakes on a large iron griddle (Comal). Ereba is eaten with fish, machuca (pounded green and ripe plantains) or alone with gravy (lasusu) often made with a fish soup called "hudutu". Other accompanying dishes may include: bundiga (a green banana lasusu), mazapan (breadfruit), and bimecacule (sticky sweet rice), as well as a coconut rice made with red beans. Nigerians also make "eba", "gari" and "fufu" from dried, grated cassava flour and similar accompanying dishes such as "efo-riro" (made from spinach leaves) or egusi" (made with grounded melon seeds) soup. An alcoholic drink called gifiti is commonly made at home; it is rum-based bitters, made by soaking roots and herbs.

Music

Garifuna music is quite different from that of the rest of Central America. The most famous form is punta. In its associated dance style, dancers move their hips in a circular motion. An evolved form of traditional music, still usually played using traditional instruments, punta has seen some modernization and electrification in the 1970s; this is called punta rock. Traditional punta dancing is consciously competitive. Artists like Pen Cayetano helped innovate modern punta rock by adding guitars to the traditional music, and paved the way for later artists like Andy Palacio, Children of the Most High, and Black Coral. Punta was popular across the region, especially in Belize, by the mid-1980s, culminating in the release of Punta Rockers in 1987, a compilation featuring many of the genre's biggest stars. Punta musicians in Central America, the US, and elsewhere made further advances with the introduction of the piano, woodwind, brass and string instruments. Punta-rock has grown since the early 1980s to include other electronic instruments such as the synthesizer and electric bass guitar as well as other percussive instruments.

Punta along with Reggaeton music are predominantly popular and influential among the entire population in Honduras. Often mixed with Spanish, Punta has a widespread audience due to the immigration of Hondurans and Guatemalan to the United States, other parts of Latin America and Europe, notably Spain. Punta bands in Honduras such as Kazzabe, Shabakan, Silver Star, Los Rolands, Banda Blanca, Los Gatos Bravos and Grupo Zambat have appeal for Latin American migrant communities. Honduran Punta has caused Belizean and Guatemalan Punta to use more Spanish due to the commercial success achieved by bands that use it.

When Banda Blanca of Honduras sold over 3 million copies of "Sopa De Caracol" ("Conch Soup"), originally written by Belizean Chico Ramos, the Garifunas of Belize felt cheated but celebrated the success. The genre is continuing to develop a strong following in the United States and South America and the Caribbean.

Belizean punta is distinctive from traditional punta in that songs are usually in Kriol or Garifuna and rarely in Spanish or English. calypso and soca have had some effect on it. Like calypso and soca, Belizean punta provides social commentary and risqué humor, though the initial wave of punta acts eschewed the former. Calypso Rose, Lord Rhaburn and the Cross Culture Band assisted the acceptance of punta by Belizean Kriol people by singing calypso songs about punta - songs such as "Gumagrugu Watah" and "Punta Rock Eena Babylon".[14]

Prominent broadcasters of Punta music include WAVE Radio and Krem Radio.

Other forms of Garifuna music and dance include: hungu-hungu, combination, wanaragua, abaimahani, matamuerte, laremuna wadaguman, gunjai, sambai, charikanari, eremuna egi, paranda, berusu, teremuna ligilisi, arumahani, and Mali-amalihani. However, punta is the most popular dance in Garifuna culture. It is performed around holidays and at parties and other social events. Punta lyrics are usually composed by the women. Chumba and hunguhungu involve circular dancing to a three-beat rhythm, which is often combined with punta. There are other types of songs typical of each gender: women having eremwu eu and abaimajani, rhythmic a cappella songs, and laremuna wadaguman; and men having work songs, chumba, and hunguhungu.

Drums play a very important role in Garifuna music. Primarily two types of drums are used: the primero (tenor drum) and the segunda (bass drum). These drums are typically made of hollowed-out hardwood, such as mahogany or mayflower, with the skins coming from the peccary (wild bush pig), deer, or sheep.

Also used in combination with the drums are the sisera, which are shakers made from the dried fruit of the gourd tree, filled with seeds, and then fitted with hardwood handles.

Paranda music developed soon after the Garifunas' arrival in Central America. The music is instrumental and percussion-based. The music was barely recorded until the 1990s, when Ivan Duran of Stonetree Records began the Paranda Project.

In contemporary Belize there has been a resurgence of Garifuna music, popularized by musicians such as Andy Palacio, Mohobub Flores, and Aurelio Martinez. These musicians have taken many aspects from traditional Garifuna music forms and fused them with more modern sounds. Described as a mixture of punta rock and paranda, this music is exemplified in Andy Palacio's album Watina, and in Umalali: The Garifuna Women's Project, both of which were released on the Belizean record label, Stonetree Records. Canadian musician Danny Michel has also recorded an album, Black Birds Are Dancing Over Me, with a collective of Garifuna musicians.[16]

In the Garifuna culture there is another dance called "dugu", which is included as part of a ritual done following a death in the family so as to pay respect to the departed loved one.

Through traditional dance and music, musicians have come together to raise awareness of HIV/AIDS.[17]

Society

Gender roles within the Garifuna communities are significantly defined by the job opportunities available to everyone. The Garifuna people have relied on farming for a steady income in the past, but much of this land was taken by fruit companies in the 20th century.[18] These companies were welcomed at first because the production helped bring an income to the local communities, but as business declined these large companies sold the land and it has become inhabited by mestizo farmers.[19] Since this time the Garifuna people have been forced to travel and find jobs with foreign companies. The Garifuna people mainly rely on export businesses for steady jobs; however, women are highly discriminated against and are usually unable to get these jobs.[20] Men generally work for foreign-owned companies collecting timber and chicle to be exported, or work as fishermen.[21]

Garifuna people live in a matrilocal society, but the women are forced to rely on men for a steady income in order to support their families, because the few jobs that are available, housework and selling homemade goods, do not create enough of an income to survive on.[22] Although women have power within their homes, they rely heavily on the income of their husbands.

Although men can be away at work for large amounts of time they still believe that there is a strong connection between men and their newborn sons. Garifunas believe that a baby boy and his father have a special bond, and they are attached spiritually.[22] It is important for a son's father to take care of him, which means that he must give up some of his duties in order to spend time with his child.[22] During this time women gain more responsibility and authority within the household.

Genetics

According to one genetic study the ancestry of the Garifuna people on average, is 76% African, 20% Arawak/Carib and 4% European.[23] The admixture levels vary greatly between island and Central American Garinagu Communities with Stann Creek, Belize Garinagu having 79.9% African, 2.7% European and 17.4% Amerindian and Sandy Bay, St. Vincent Garinagu having 41.1% African, 16.7% European and 42.2% Amerindian.[24]

Economics

The Garifuna culture is greatly affected by the economic atmosphere surrounding the community. This makes the communities extremely susceptible to outside influence. Many worry that the area will become extremely commercialized since there are few economic opportunities within it.[25]

Notable Garifuna

- Joseph Chatoyer

- Barauda ( wife of Joseph Chatoyer )

- Theodore Aranda

- Rosita Baltazar

- Mirtha Colón

- Abraham Laboriel

- Abe Laboriel Jr.

- Aurelio Martínez

- Bernard Martínez Valerio

- Paul Nabor

- Rakeem Nuñez-Roches

- Clifford Palacio

- Miriam Miranda

- Trevor “ Aura Buni Amurü Nuni” Palacio

See also

References

- Post Rust, Susie. "Fishing villages along Central America's coast pulse with the joyous rhythms of this Afro-Caribbean people". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 17 November 2007. Retrieved 21 September 2007.

- "2005 American Community Survey: Race and Hispanic or Latino". U.S. Census Bureau. 2000. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- "Garifuna". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Garifuna". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- Remembering How Anthony Bourdain Advocated for Latinos Published June 8, 2018, retrieved June 15, 2018

- Haurholm-Larsen, Steffen (22 September 2016). A Grammar of Garifuna: A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Humanities Department of Linguistics University of Bern in pursuit of the title Doctor of Philosophy. p. 6.

- Crawford, MH; Gonzalez, NL; Schanfield, MS; Dykes, DD; Skradski, K; Polesky, HF (February 1981). "The Black Caribs (Garifuna) of Livingston, Guatemala: Genetic Markers and Admixture Estimates". Human biology. 53 (1): 87. PMID 7239494.

- Wilfried Raussert (6 January 2017). The Routledge Companion to Inter-American Studies. Taylor & Francis. p. 390. ISBN 978-1-317-29065-0.

- Sweeney, James L. (2007). "Caribs, Maroons, Jacobins, Brigands, and Sugar Barons: The Last Stand of the Black Caribs on St. Vincent", African Diaspora Archaeology Network, March 2007, retrieved 26 April 2007

- "Institutional History of Martinique" Archived 25 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Martinique Official site, French Government (translation by Maryanne Dassonville). Retrieved 26 April 2007

- Young, Black Charaibs, pp. 12–13.

- Young, Black Charaibs, p. 4.

- Garsd, Jasmine. " VIVA LA LIBRE CIRCULACIÓN DE PERSONAS Garifuna: The Young Black Latino Exodus You’ve Never Heard About" (Archive). Fusion. June 4, 2014. Retrieved on September 7, 2015.

- Anderson, Mark. "Black Indigenism: The Making of Ethnic Politics and State Multiculturalism", Black and Indigenous: Garifuna Activism and Consumer Culture in Honduras. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009: 136.

- Sletto, Jacqueline W. "ANCESTRAL TIES THAT BIND." America 43.1 (1991): 20–28. Print.

- "World Cafe Next: Danny Michel And The Garifuna Collective". NPR, 15 July 2013.

- "The Forgotten: HIV and the Garifuna of Honduras". Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- Women and Religion in the African Diaspora: Knowledge, Power, and Performance, page 51, 2006.

- Neither Enemies Nor Friends: Latinos, Blacks, Afro-Latinos, page 105, 2005.

- Sex Roles and Social Change in Native Lower Central American Societies, page 24, 1982.

- Sex Roles and Social Change in Native Lower Central American Societies, page 25, 1982.

- Chernela, Janet M. Symbolic Inaction in Rituals of Gender and Procreation among the Garifuna (Black Caribs) of Honduras Ethos 19.1 (1991): 52–67.

- Crawford, M.H. 1997 Biocultural adaptation to disease in the Caribbean: Case study of a migrant population Archived 5 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Journal of Caribbean Studies. Health and Disease in the Caribbean. 12(1): 141–155.

- Crawford, M.H. 1983 The anthropological genetics of the black The anthropological genetics of the Black Caribs (Garifuna) of Central America and the Caribbean . Yearbook of Physical Anthropology. 26: 161-192 (1983).

- Anderson, Mark. When Afro Becomes (like) Indigenous: Garifuna and Afro-Indigenous Politics in Honduras. Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 12.2 (2007): 384–413.

- "Nunez-Roches helps others". Hattiesburg American. 26 November 2014.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Mark. When Afro Becomes (like) Indigenous: Garifuna and Afro-Indigenous Politics in Honduras. Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology 12.2 (2007): 384–413. AnthroSource. Web. 20 January 2010.

- Breton, Raymond (1877) [1635]. Grammaire caraibe, composée par le p. Raymond Breton, suivie du Catéchisme caraibe. Bibliothèque linguistique américaine, no. 3 (1635 original MS. republication ed.). Paris: Maisonneuve. OCLC 8046575.

- Chernela, Janet M. Symbolic Inaction in Rituals of Gender and Procreation among the Garifuna (Black Caribs) of Honduras. Ethos 19.1 (1991): 52–67. AnthroSource. Web. 13 January 2010.

- Dzizzienyo, Anani, and Suzanne Oboler, eds. Neither Enemies Nor Friends: Latinos, Blacks, Afro-Latinos. 2005.

- Flores, Barbara A.T. (2001) Religious education and theological praxis in a context of colonization: Garifuna spirituality as a means of resistance. Ph.D. Dissertation, Garrett/Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois. OCLC 47773227

- Franzone, Dorothy (1995) A Critical and Cultural Analysis of an African People in the Americas: Africanisms in the Garifuna Culture of Belize. PhD Thesis, Temple University. UMI Dissertation Services (151–152). OCLC 37128913

- Gonzalez, Nancie L. Solien (1988). The Sojourners of the Caribbean: Ethnogenesis and Ethnohistory of the Garifuna. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01453-6. OCLC 15519873.

- Gonzalez, Nancie L. Solien (1997). "The Garifuna of Central America". In Samuel M. Wilson (ed.). The Indigenous People of the Caribbean. The Ripley P. Bullen series. Organized by the Virgin Islands Humanities Council. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. pp. 197–205. ISBN 978-0-8130-1531-6. OCLC 36817335.

- Griffith, Marie, and Darbara Dianne Savage, eds. Women and Religion in the African Diaspora: Knowledge, Power, and Performance. 2006.

- Herlihy, Laura Hobson. Sexual Magic and Money: Miskitu women’s Strategies in Northern Honduras. Ethnology 46.2 (2006): 143–159. Web. 13 January 2010.

- Loveland, Christine A., and Frank O. Loveland, eds. Sex Roles and Social Change in Native Lower Central American Societies.

- McClaurin, Irma. Women of Belize: Gender and Change in Central America. 1996. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 2000.

- Palacio, Myrtle (1993). The First Primer on the People Called Garifuna. Belize City: Glessima Research & Services. OCLC 30746656.

- Sutherland, Anne (1998). The Making of Belize: Globalization in the Margins. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey. ISBN 978-0-89789-579-8. OCLC 38024169.

- Taylor, Christopher (2012). The Black Carib Wars: Freedom, Survival, and the Making of the Garifuna. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Garifuna. |

- Garifuna Heritage Foundation – St Vincent

- Garifuna Research Institute

- Garifuna Heritage Foundation

- Garifuna in Honduras

- Warasa Garifuna Drum School

- Garífunas Confront Their Own Decline by Michael Deibert, Inter Press Service, Oct 6, 2008

- Examining the impact of changing livelihood strategies upon Garifuna Cultural Identity, Cayos Cochinos, Honduras

- The Garifuna on NationalGeographic.com

- Garifuna.org

- ONECA (Organización Negra Centroamericana)

- Vacation in Hopkins a Garifuna Community

- Pen Cayetano

- – "We are free" Mali Cayetano