Aluku

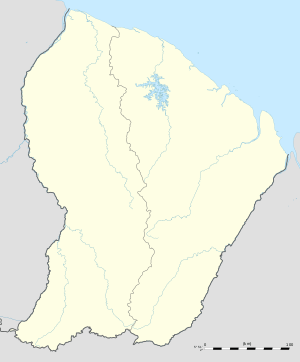

The Aluku are a Bushinengue ethnic group living mainly on the riverbank in Maripasoula in southwest French Guiana. The group are sometimes called Boni, referring to the 18th-century leader, Bokilifu Boni.

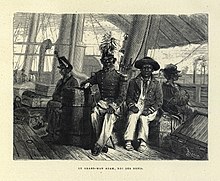

Granman Adam (1862 or 63) | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 11,600[1] (2018, est.) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Tribal French Guiana (Maripasoula & Papaïchton) | 6,600 |

| Urban French Guiana (mainly Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni) | 3,200 |

| Internationally | 1,800 |

| Languages | |

| Aluku, French | |

| Religion | |

| Winti | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ndyuka | |

| Granman of the Aluku people | |

|---|---|

| Residence | Maripasoula |

History

The Aluku are an ethnic group in French Guiana whose people are descended in part from African slaves who escaped in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries from the Dutch plantations in what is now known as Suriname.[3] Intermarrying with Native Americans, toward the end of the eighteenth century, they initially settled east of the Cottica River in what is nowadays the Marowijne District in Suriname.[4] They were initially called Cottica-Maroons.[5]

Boni Wars

In 1760, the Ndyuka people who lived nearby, signed a peace treaty with the colonists offering them territorial autonomy.[6] The Aluku also desired a peace treaty, however the Society of Suriname, started a war against them[7] In 1768, the first village was discovered and destroyed.[8]

In 1770, two other Maroon groups joined the tribe which became known as the Boni after their leader.[5] Boni used guerilla tactics against the colonists, and kept retreating into the heavily guarded Fort Boekoe located in a swamp.[9] On 20 September 1772,[9] after seven months of fighting, an army of 300 freed slaves finally managed to conquer the fort.[5] The Aluku moved southwards, and settled along the Lawa River,[7] a river that formed the border between French Guiana and Suriname. The Ndyuka initially attacked them for encroaching into their territory. In late 1779, a peace treaty was signed between the two tribes, and Boni promised not to raid the Dutch plantations.[10] During the period of peace, the Aluku had been approached by the French to settle on the La Mana River. Boni did not trust them, and had ignored the offer.[11]

Peace was maintained until 1788 when plantation Clarenbeek was attacked.[10] In 1789,[10] the neighbouring Ndyuka joined forces with the colonists,[5][7] and by 1791 Lieutenant colonel Beutler had chased the remaining Aluku from Suriname into French Guiana.[7] On 19 February 1793, Bokilifu Boni was killed by Bambi, a Ndyuka chief.[5]

Stateless people

Between 1793 and 1837, the Aluku settled around Gaa Daï (Abunasunga).[12] During that period, there were close contacts with the Amerindian Wayana tribe with two tribes often living together in the same villages.[13] In 1815 the Aluku and Wayana became blood brothers.[14]

In 1836, the Navy chemist Le Prieux, who was on an expedition to the southern border of French Guiana, arrived at the Aluku. Le Prieux pretended that he was on an official mission, and made a peace treaty on behalf of the French State. He also installed Gongo as granman. When the Ndyuka granman Beeyman heard about this, he summoned Gongo and told him that the treaty was unacceptable. Fearing a French invasion, Beeyman mobilized his army. This turn of events, upset the Surinamese government who asked Gongo to stand down his army, and that they would contact the French Governor. On 9 November 1836 an agreement was signed between French Guiana and Suriname stating that Le Prieux had no authority whatsoever, and that the Aluku should leave the French territory and submit to the Ndyuka.[15]

On 7 July 1841, a delegation of 12 people was sent to the French Governor to ask permission to settle on the Oyapock River,[12] however 11 including granman Gongo were killed.[16] Therefore, attempts at diplomacy were abandoned, and part of the tribe settled on the Lawa River where they founded the villages Pobiansi,[12] Assissi, Puumofu and Kormontibo.[17] In 1860, the Ndyuka on the centennial of their autonomy, signed a peace treaty with the Aluku in Albina, and allowed them to settle in Abunasunga.[12]

French period

In 1891, Czar Alexander III of Russia was asked to delimit the border between French Guiana and Suriname. Both nations promised to respect the rights of the tribes living on the islands,[18] therefore tribes living on the river had to choose their nationality. A meeting was called in Paramaribo with granman Ochi to persuade the Aluku to become Dutch citizens.[18] The Aluku opted for French citizenship on 25 May 1891.[17] One of Aluku elders used the following words: "Sir, when you have a chicken whom you never feed, and your neighbour takes care of the animal would you think that the animal would stay with you, or do you think that it will leave and go to your neighbour? Well, the same applies to us."[19]

Until the dissolution of the Inini territory in 1969, the Aluku lived autonomously with little or no interference of the French government.[3] Along with the establishment of communes, came a government structure, and francisation.[3] It has resulted into two incompatible systems (traditional government and communes) existing side-by-side where the communes keep on gaining the upper hand.[20] Most importantly, it led to the concentration in bigger villages and the near abandonment of smaller settlements.[3]

In February 2018, the Grand Conseil coutumier des Populations Amérindiennes et Bushinengué (Great traditional council of Amerindian and Maroon populations) was established with six Aluku Captains and two Aluku leaders among its members.[21] One of the main issues raised in 2009, was the absence of traditional leaders from the working sessions of the municipal council.[22]

The Aluku granman used to reside in Papaïchton. In 1992, there were two granman installed,[23] Paul Doudou who was granman in Papaïchton until his death in 2014,[24] and Joachim-Joseph Adochini who was chosen by election, and not part of maternal lineage.[25] Adochini resides in Maripasoula.[2]

Settlements

In the late eighteenth century, the Aluku had settlements in the region of Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni, Apatou, and Grand-Santi.[3]

The main settlements are in the county of Maripasoula, consisting of:

- the municipalities and city of Maripasoula and the capital city of Papaïchton, and the traditional villages of Kormontibo, Assissi, Loca, Tabiki, and Agoodé, in French Guiana; and

- Cottica, in Suriname.[17] Abandoned during the Boni Wars, but resettled in 1902.[26]

A large part of the Aluku population resides in the urban areas of Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni, Cayenne, Matoury, and Kourou in French Guiana.[27] Many Aluku in Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni live in makeshift "villages" on the outside of town without any infrastructure.[28] The urban population was estimated at about 3,200 people in 2018.[1]

Economy and agriculture

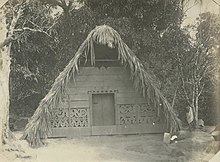

Traditionally, the Aluku people lived by subsistence farming, hunting, gathering, and fishing. Necessities were obtained by trading with neighbouring Maroon and indigenous tribes.[3] There was a moral obligation to share among the clan.[29] There were many smaller villages with farms around the main settlements to prevent depletion of the soil.[3]

They have adapted in part to modernity, taking part in the market economy, and the consumption society. Some are hired by the Army as river boat drivers. According to Bernard Delpech, the Aluku have undergone "destabilization of the basic traditional material, cultural transformation, altering the rules of collective life".[30]

Religion

The traditional religion of the Maroon people was Winti, a synthesis of African religion traditions.[31] Among the Matawai and Saramaka people in Suriname, the missionary activities of the Moravian Church using Maroon missionaries[32] resulted in a large scale conversion to Christianity. In French Guiana, the Jesuits had been active under the Amerindian tribes, however the introduction of European diseases forced the Jesuits to cease their activities in 1763.[33] The absence of missionary activities among the Aluku preserved continuation of Winti as the dominant religion.[31]

The main god for the Aluku is Odun, Four Pantheons, mystical spirits, are distinguished which play an integral part in everyday life. The funeral rites are very extensive,[34] and can last many months.[31]

Language

| Aluku | |

|---|---|

| Aluku or Boni | |

| Native to | French Guiana, Suriname |

Native speakers | c. 6,000 (2002)[35] |

English Creole

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | aluk1239[36] |

Aluku (also Aluku Tongo[37]) is the eponymous term for their language. Richard Price estimated about 6,000 speakers in 2002.[35] Many of its speakers are also bilingual in French.

The Aluku language is a creole of English (inherited from the British colonies that took over from the Dutch in Suriname) as well as Dutch, a variety of African languages and,[38] more recently, French.[3] The language is derived from Plantation Creole which is nowadays known as Sranan Tongo, however the branch diverted around 1712, and evolved separately.[37]

It is related and mutual intelligibile to the languages spoken by the Pamaka and Ndyuka peoples.[39] The main difference is in the phonological system and lexicon used.[37]

See also

References

- Price 2018, Table 1.

- "Statement by Gaanman Joachim-Joseph Adochini, Paramount Chief of the Aluku (Boni) People". Smithsonian Institution. 1992. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- "The Aluku and the Communes in French Guiana". Cultural Survival. September 1989. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- Wim Hoogbergen, (2015), De Boni-oorlogen Slavenverzet, marronage en guerrilla, Vaco, Paramaribo p71 (in dutch)

- "Boni (ca. 1730 – 1793), leider van de slavenrevoltes in Suriname". Is Geschiedenis (in Dutch). Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "The Ndyuka Treaty Of 1760: A Conversation with Granman Gazon". Cultural Survival (in Dutch). Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "Encyclopaedie van Nederlandsch West-Indië - Page 154 - Boschnegers" (PDF). Digital Library for Dutch Literature (in Dutch). 1916. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- Dobbeleir 2008, p. 13.

- "Op zoek naar Fort Boekoe". Trouw (in Dutch). Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- Groot 1970, p. 294.

- Fleury 2018, p. 23.

- "L'historie des Boni en Guyane at du Suriname". nofi.media (in French). Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- Fleury 2018, p. 30.

- Fleury 2018, p. 32.

- Scholtens 1994, p. 29.

- Scholtens 1994, p. 30.

- "Parcours La Source". Parc-Amazonien-Guyane (in French). Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Scholtens 1994, p. 63.

- Scholtens 1994, p. 65: "Meneer, wanneer u een kip er op nahoudt, die u nooit te eten geeft en uw buurman trekt zich het lot van het dier aan, zoudt u dan denken, dat het beest bij u zou blijven, of gelooft u ook niet, dat het u zal verlaten en naar uw buurman gaan? Welnu, datzelfde is het geval met ons."

- Scholtens 1994, p. 117.

- Price 2018, pp. 275-283.

- "L'heure du bilan pour le Grand Conseil coutumier". Guyane la 1ère (in French). Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- Bassargette & Di Meo 2008, p. 57.

- "Décès du Gran Man Paul Doudou : les condoléances". Blada (in French). Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Scholtens 1997, p. 120.

- Scholtens 1994, pp. 65-68.

- Kenneth M. Bilby (1990). "The remaking of the Aluku: culture, politics, and Maroon ethnicity in French South America". Yale University. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- Delpech 1993, p. 187.

- Delpech 1993, p. 178.

- Delpech 1993, p. 175.

- Richard Price (1987). "Encyclopedia of Religions" (PDF). Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- "Creole drum". Digital Library for Dutch Literature. 1975. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "Guide Camopi". Petit Futé (in French). Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "Aluku". Populations de Guyane (in French). Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- "Survey chapter: Nengee". Apics Online.info. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Aluku". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- Bettina Migge (September 2003). "Grammaire du nengee: Introduction aux langues aluku, ndyuka et pamaka". Research Gate (in French). Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- Borges 2014, p. 188.

- Borges 2014, pp. 97-98.

Bibliography

- Bassargette, Denis; Di Meo, Guy (2008). "Les limites du modèle communal français en Guyane : le cas de Maripasoula". Open Edition (in French).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Borges, Roger (2014). The Life of Language. Dynamics of language contact in Suriname (PDF) (Thesis). Utrecht: Radboud University Nijmegen.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Delpech, Bernard (1993). "Les Aluku de Guyane à un tournant : de l'économie de subsistance à la société de consommation". Persée. Les Cahiers d’Outre-Mer nº 182 (in French). Retrieved 23 July 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dobbeleir, Céline (2008). De politieke mobilisatie en organisatie van vijf etnische groepen in Suriname (PDF). Kennis Bank SU (in Dutch). University of Gent.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fleury, Marie (2018). "Gaan Mawina, le Marouini (haut Maroni) au cœur de l'histoire des Noirs marrons Boni/Aluku et des Amérindiens Wayana". Open edition. Revue d’ethnoécologie 13, 2018 (in French).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Groot, Silvia, de (1970). "Rebellie der Zwarte Jagers. De nasleep van de Bonni-oorlogen 1788-1809". Digital Library of Dutch Literature. De Gids (in Dutch).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Price, Richard (2018). "Maroons in Guyane". New West Indian Guide / Nieuwe West-Indische Gids Volume 92: Issue 3-4. Brill Publishers. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Scholtens, Ben (1994). Bosneger en overheid in Suriname. Radboud University Nijmegen (Thesis) (in Dutch). Paramaribo: Afdeling Cultuurstudies/Minov. ISBN 9991410155.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External link