Black Caribs

Black Caribs refer to the Garifuna ethnic group native to the island of St. Vincent. The Black Caribs or Garinagu are a mix of Amerindian and African people native to the island of Yurumein now called St Vincent. The Garifuna, singular of Garinagu, population retains the traditional Caribbean culture and language. The Garifuna people and Nation has grown significantly since their major wars with the British empire, which resulted in their exile from St Vincent. On April 12, 1797 only 2,000 Garinagu arrived on Roatan from over 4,000 originally expelled to the island of Baliceuax, near Yurumein, now known as St Vincent, the homeland of the Garinagu people. The terrible loss of life due to genocide by the British. In 2018 over 800,000 people have been traced as descendants of those original 2,000 Garifuna people who reached Roatan. The history of the Black Caribs or Garinagu is widely evidenced & known due to the diaries of Columbus who wrote of the large African presence on St Vincent during his voyage there in the 1490s as outlined by Dr Barry Fell, PhD Harvard University. The 1700 British colonists have also wrote about Black Carib presence in St Vincent in their early diaries held in the British archives. Many of the Black Caribs or Garifuns were expelled from St. Vincent in 1797 and exported to the island of Roatán, Honduras, from there the majority migrated to the coast of the mainland of Central America, spread as far as Belize and Nicaragua, There is a small settlement remaining in St Vincent.[1]

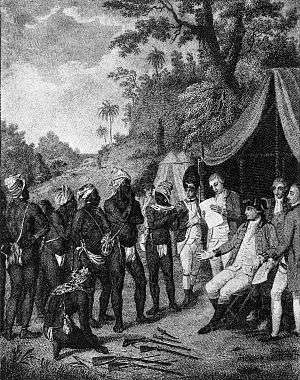

Depiction of treaty negotiations between Black Caribs and British authorities on the Caribbean island of Saint Vincent, 1773. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Unknown up to 2.0% of the Caribbean Community | |

| Languages | |

| English | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Garifuna people, Afro-Vincentians, English colonists, Zambos |

History

Upon arrival of the Europeans, the island of St. Vincent was populated by the indigenous Black Carib (Garifuna) It is said that the Black Carib (Garifuna) were also excellent fishermen.

William Young's version

After the arrival of the British to St. Vincent in 1667, the British Major John Scott wrote a report for the British crown, explaining that St. Vincent was populated by indigenous people and some blacks from two Spanish ships wrecked on its shores. Later, in 1795, the British governor of St. Vincent, William Young, explained in another report, also addressed to the British Crown, the island was populated by black slaves from two Spanish ships that had sunk near the island of San Vincent in 1635 (although according other authors as Idiáquez, the two slave ships wrecked between 1664 and 1670). The ships carrying slaves headed to the West Indies (Bahamas and Antilles). According to Young's report, after the wreck, slaves from the ethnic group Hebo (Negro) from Nigeria, escaped and reached the small island of Bequia. There, the yellow Caribs enslaved them and brought them to Saint Vincent. However, according to Young, the slaves were too independent of "spirit", prompting Caribbean teachers to plan to kill all the African male children. When Africans heard about the yellow Caribs' plan, they rebelled and killed all the Caribs they could, then headed to the mountains, where they settled and lived with other slaves who had taken refuge there before them. From the mountains, the former slaves attacked and killed the Caribs continually, reducing them in number.[1]

Current version

However, researchers such as the linguist specializing in the Garifuna language Itarala, reject the theory of Young. According to them, most of the slaves arrived in Saint Vincent came, actually, from other Caribbean islands, who had settled in Saint Vincent in order to escape slavery in his land. So, to Saint Vincent, came Maroons from all surrounding plantations from the islands, but were diluted in the strong culture of resistance Caribbean.[2] Although most of the slaves came from Barbados [1] (most of the slaves of this island were of present Nigeria and Ghana), but slaves also came from places like St. Lucia (where slaves were probably from the present Senegal, Nigeria, Angola (Ambundu) and Akan people) and Grenada (where there were many slaves from Guineas, Sierra Leone, Nigeria (specifically Igbo), Angolans, Yoruba, Kongo and Ghana). The Bajans and Saint Lucians arrived on the island in pre-1735 dates. Later, after 1775, most of the slaves who came running from other islands were Saint Lucians and Grenadians.[3] After arriving at the island, they were received by the Caribs, who offered protection,[4] enslaved them [5] and, eventually, mixed with them.

In addition to the African refugees, the Caribs captured slaves from neighboring islands (although they also had white people and their own people as slaves), while they were in fighting against the British and French. Many of the captured slaves were integrated into their communities (this also occurred in islands like Dominica). After the African rebellion against the Caribs, and their escape to the mountains, over time, according to Itarala, the Africans from the mountains would come down from the mountains to have sexual intercourse with Amerindian women - perhaps because most Africans were men - or to search for other kinds of food.[4] The sexual intercourse did not necessarily lead to marriage.

On the other hand, if the Maroons abducted to Arauaco-Caribbean women or married them, is another of the contradictions between the French documents and memory of the Garinagu. Andrade Coelho states that "whatever the case, the Caribs never consented to give their daughters in marriage to blacks".[6] Conversely, Sebastian R. Cayetano, argues that "Africans were married with women Caribs of the islands, giving birth to the Garifuna".[7] According to Charles Gullick some Caribs were mixed peacefully with the Maroons and some not, creating two factions, that of the Black Caribs and the Yellow Caribs, who fought on more than one occasion in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth.[8] According to Itarala, many intermarried between indigenous and African people, was which caused the origin of the Black Caribs.[4]

One datum in favour of the idea of Gullick is the physical separation between black Caribs and Yellow Caribs in the late 17th century. Perhaps because of its numerical dominance, the black community pushed the Yellow Caribs towards the leeward side of the island, staying them with the most flat and fertile part (but also more liable to be attacked from the sea) of windward. It also seems true that in 1700 the Yellows asked the intervention of the French against the Black Caribs, however, when visualized they should share their scarce land, preferred to give up the alliance.[9]

Carib wars

When in 1627 the British began to claim the St. Vincent island, they opposed the French settlements (which had started around 1610 by cultivating plots) and its partnerships with the Caribs. Over time, the Black Caribs were getting power and social prestige on the other native peoples and they were considered by the British, who wanted to occupy the island and give it to the British Crown, as a threat that had to be eradicated. The governor of the island, William Young, complained that the Black Caribs had the best land and they had no right to live there. Moreover, the friendship of the French settlers with the Black Caribs, drove them, even though they had also tried to stay with San Vicente, tried to support them in their struggle. All this caused the "War Caribbean". The First Carib War began in 1769. Led primarily by Black Carib chieftain Joseph Chatoyer, the Caribs successfully defended the windward side of the island against a military survey expedition in 1769, and rebuffed repeated demands that they sell their land to representatives of the British colonial government. The effective defense of the Caribs, the British ignorance of the region and London opposition to the war made this be halted. With military matters at a stalemate, a peace agreement was signed in 1773 that delineated boundaries between British and Carib areas of the island.[4] The treaty delimited the area inhabited by the Caribs, and demanded repayment of the English and French plantations of runaway slaves who took refuge in St. Vincent. This last clause, and the prohibition of trade with neighbouring islands, so little endeared the Caribs. Three years later, the French supported American independence (1776-1783);[10] the Caribs aligned against the British. Apparently, in 1779 the Caribs inspired such terror to the British colonists that surrender to the French was preferred than firing a gun.[11]

Later, in 1795, the Caribs again rebelled against British rule of the island, causing the Second Carib War. This war was very bloody, and had the extra incentive, after its completion, the epidemic spread of a deadly disease that killed most of the Black Caribs. Despite them, the Caribs successfully gained control of most of the island except for the immediate area around Kingstown, which was saved from direct assault on several occasions by the timely arrival of British reinforcements. British efforts to penetrate and control the interior and windward areas of the island were repeatedly frustrated by incompetence, disease, and effective Carib defences, which were eventually supplemented by the arrival of some French troops. A major military expedition by General Ralph Abercromby was eventually successful in crushing the Carib opposition in 1796.

After the war, the surrender the Caribs to the British and be regarded as enemies his, the British decided to expel the Caribs of St. Vincent by force. In this way, and in that year, two Englishmen wrote reports to the British crown explaining that slaves that had arrived in San Vicente, already they not were native of there (they not were indigenous or settlers) and the British had not brought them, they should be deported. The intent of this document was, as we have said, probably, that the crown would allow them to deport the Black Caribs from the island, because they were enemies of the British and allies of the French.

To make the document was credible, William Young indicated a particular location from which the slaves came: Nigeria and a specific ethnic group: Ibibios, and there were indicated that the slaves came, according to the author, from two Spanish or a Spanish and a Dutch ships that had sunk into the shores of the island in 1635 and that the slaves who survived the sinking were established on the island (after the publication of these reports, later chroniclers merely simply copy this information over and over again until the event became well known). Thus, the crown allowed them that the Black Caribs were deported and, in 1797, the British chose between the Black Caribs slaves darker or more African traits had inherited, considering them as the cause of the revolt, and originally exported them to Jamaica, and then they were transported to the island of Roatan in Honduras. Meanwhile, the Black Caribs with higher Amerindian traits were maintained on the island. Such, more than 5,000 Black Caribs were deported, but when the British landed on Roatan on April 12, 1797, only about 2,500 survived the trip to the islands. Since that this was too small and infertile to maintain the population, the Black Caribs asked the Spanish authorities of Honduras to be allowed to live on land. The Spanish are allowed to change the use them as soldiers. After settling in the Honduran coast, they were expanded by the Caribbean coast of Central America, coming to Belize and Guatemala to the north, and the south to Nicaragua. Over time, the Black Caribs would be denominated in the mainland of Central America as "Garifuna". This word, according to Gonzalez (2008, p. Xv), derived from "Kalinago", the name by which were designated by Spanish peoples when found them in the Lesser Antilles on arrival in the region since 1492.[1]

Demography

The Black Caribs currently make up 2% of the population of St. Vincent and Grenadines. They excelled in commercial activities, negotiation and alliances with other people. The Black Caribs currently have their villages flanking the volcano, and are known as the poorest people on St. Vincent and Grenadines.The Black Caribs were also agricultural and navigation techniques and military skills, which were recognized by the colonial authorities and the European settlers of the island. Besides that they were also important ritual practices, whose realization is established in relation to dead people and illness (now called "ancestor worship"). These activities still characterize the Black Caribs as specific ethnic people.[12]

African origins of the Black Caribs

It is likely that the document was written for Young was written for expel Black Caribs rebels because in reality, we know that no slave ship came to the island ever directly from Africa. (nor did any of the dozens of registered vessels that crashed between 1630 and 1680 crash into the island or anywhere close. All of those registered vessels were marked "triumphant" and crashed during those years.) We also know that slave ships that came to the Americas were laden with slaves from different areas and ethnic groups from Africa with their own languages, to try to prevent slaves from speaking to each other and riot or revolt, which would endanger slavery. The slaves did not come from a single village, as Young tried to convince.

So, according to some authors, basing on oral tradition of the Black Caribs and Garifuna, they are descendants of Caribbeans with the African origins Efik (Nigeria-Cameroon residents), Ibo (Nigerian), Fons (residents between Benin - Nigeria), Ashanti (from Ashanti Region, in central Ghana), Yoruba (resident in Togo, Benin, Nigeria) and Kongo (resident in Gabon, Congo, DR Congo and Angola), obtained in the coastal regions of West and Central Africa by Spanish and Portuguese traders of slaves. This slaves were trafficked to other Caribbean islands, from where emigrated or were captured (they or their descendants) to Sain Vicent.[13]

In this way, the anthropologist and Garifuna historian Belizean Sebastian R. Cayetano says African ancestors of the Garifuna are ethnically West African "specifically of the Yoruba, Ibo, and Ashanti tribes, in what is now Ghana, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone, to mention only a few." [14] To Roger Bastide, the Garifuna almost inaccessible fortress of Northeast Saint Vincent integrated constantly to Yoruba, Fon, Fanti-Ashanti and Kongo fugitives.[15] These African origins are true at least in the masculine gender. For the female gender, the origins comes from the union of black slaves with Caribs.[13] Based on 18th-century English documents, Ruy Galvao de Andrade Coelho suggests that came from Nigeria, Gold Coast, Dahomey, Congo "and other West African regions".[16]

At the beginning of the 18th century the population in Saint Vincent was already mostly black and although during this century there were extensive mixtures and black people and Carib Indians, they kept the existence of a ″racially pure″ Caribbean group, which was called Red Caribs to differentiate the Black Caribs.[1]

See also

- Afro-Vincentian

- Garifuna people

References

- Garifuna reach: Historia de los garífunas. Posted by Itarala. Retrieved 19:30 pm.

- “Escala de intensidad de los africanos en el Nuevo Mundo”, ibidem, p. 136.

- A Brief History of St. Vincent Archived 2013-04-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Marshall, Bernard (December 1973). "The Black Caribs — Native Resistance to British Penetration Into the Windward Side of St. Vincent 1763-1773". Caribbean Quarterly (Vol. 19, Number 4). JSTOR 23050239.

- Charles Gullick, Myths of a minority, Assen: Van Gorcum, 1985.

- R. G. de Andrade Coelho, page. 37.

- Ibidem, p. 66

- Charles Gullick, “Ethnic interaction and carib language”, page. 4.

- Ensayos de Libros: Garifuna - Caribe.(Trials of Books)

- David K. Fieldhouse. Los imperios coloniales desde el siglo XVIII (in Spanish: Colonial Empires since the 18th century). Mexico: Siglo XXI, 1984, page 36.

- Rafael Leiva Vivas, page. 139

- "Afrodescendencia" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-08-18. Retrieved 2013-06-03.

- Jesús Muñoz Tábora (2003). Instrumentos musicales autóctonos de Honduras (in Spanish: Indigenous musical instruments of Honduras). Editorial guaymuras, Tegucigalpa, Honduras. p. 47. Second Edition.

- Garifuna History, language, and Culture, page 32.

- Roger Bastide. African Civilizations in the New World. Londres: Hurst, 1971, p. 77.

- Ruy Galvão de Andrade Coelho. Los negros caribes de Honduras, page. 36