Gansu

Gansu (![]()

Gansu Province 甘肃省 | |

|---|---|

| Name transcription(s) | |

| • Chinese | 甘肃省 (Gānsù Shěng) |

| • Abbreviation | GS / 甘 or 陇 (pinyin: Gān / Lǒng) |

(clockwise from top)

| |

.svg.png) Map showing the location of Gansu Province | |

| Coordinates: 38°N 102°E | |

| Named for | 甘 gān: Ganzhou District, Zhangye 肃/肅 sù: Suzhou District, Jiuquan |

| Capital (and largest city) | Lanzhou |

| Divisions | 14 prefectures, 86 counties, 1344 townships |

| Government | |

| • Secretary | Lin Duo |

| • Governor | Tang Renjian |

| Area | |

| • Total | 453,700 km2 (175,200 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 7th |

| Highest elevation | 5,830 m (19,130 ft) |

| Population (2010)[1] | |

| • Total | 25,575,254 |

| • Rank | 22nd |

| • Density | 56/km2 (150/sq mi) |

| • Density rank | 27th |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic composition | Han: 91% Hui: 5% Dongxiang: 2% Tibetan: 2% |

| • Languages and dialects | Zhongyuan Mandarin, Lanyin Mandarin, Amdo Tibetan |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-GS |

| GDP (2017[2]) | CNY 767.70 billion USD 113.70 billion (27th) |

| • per capita | CNY 29,326 USD 4,343 (31st) |

| HDI (2018) | medium · 27th |

| Website | Gansu.gov.cn (Simplified Chinese) |

| Gansu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png) "Gansu" in Simplified (top) and Traditional (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 甘肃 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 甘肅 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "Gan (zhou) and Su (zhou)" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tibetan | ཀན་སུའུ་ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The seventh-largest administrative district by area at 453,700 square kilometres (175,200 sq mi), Gansu lies between the Tibetan and Loess plateaus and borders Mongolia (Govi-Altai Province), Inner Mongolia and Ningxia to the north, Xinjiang and Qinghai to the west, Sichuan to the south and Shaanxi to the east. The Yellow River passes through the southern part of the province. Part of Gansu's territory is located in the Gobi Desert. The Qilian mountains are located in the south of the Province.

Gansu has a population of 26 million, ranking 22nd in China. Its population is mostly Han, along with Hui, Dongxiang and Tibetan minorities. The most common language is Mandarin. Gansu is among the poorest administrative divisions in China, ranking 31st in GDP per capita. Most of Gansu's economy is based on the mining industry and the extraction of minerals, especially rare earth elements. Tourism also plays a role in Gansu's economy.

The State of Qin originated in what is now southeastern Gansu and went on to form the first known Empire in what is now China. The Northern Silk Road ran through the Hexi Corridor, which passes through Gansu, resulting in it being an important strategic outpost and communications link for the Chinese empire.

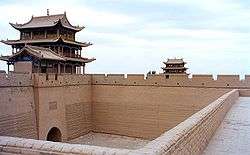

The city of Jiayuguan, the second most populated city in Gansu, is known for its section of the Great Wall and the Jiayuguan Pass fortress complex.

Name

Gansu is a compound of the names of Gānzhou (now the main urban district and seat of Zhangye) and Sùzhou (an old name and the modern seat of Jiuquan), formerly the two most important Chinese settlements in the Hexi Corridor.

Gansu is abbreviated as "甘" (Gān) or "陇" (Lǒng), and was also known as Longxi (陇西; '"[land] west of Long"') or Longyou (陇右; '"[land] right of Long"') prior to early Western Han dynasty, in reference to the Long Mountain (the modern day Liupan Mountain's southern section) between eastern Gansu and western Shaanxi.

History

Gansu's name is a compound name first used during the Song dynasty. It is a combination of the names of two prefecture (州) in the Sui and Tang dynasty: Gan (around Zhangye) and Su (around Jiuquan). Its eastern part forms part of one of the cradles of ancient Chinese civilisation.

Ancient Gansu

In prehistoric times, Gansu was host to Neolithic cultures. The Dadiwan culture, from where archaeologically significant artifacts have been excavated, flourished in the eastern end of Gansu from about 6000 BC to about 3000 BC.[5] The Majiayao culture and part of the Qijia culture took root in Gansu from 3100 BC to 2700 BC and 2400 BC to 1900 BC respectively.

The Yuezhi originally lived in the very western part of Gansu until they were forced to emigrate by the Xiongnu around 177 BCE.

The State of Qin, known in China as the founding state of the Chinese empire, grew out from the southeastern part of Gansu, specifically the Tianshui area. The Qin name is believed to have originated, in part, from the area.[6][7] Qin tombs and artifacts have been excavated from Fangmatan near Tianshui, including one 2200-year-old map of Guixian County.[8]

Imperial era

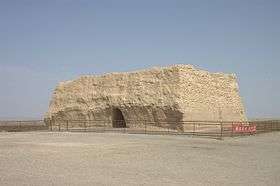

In imperial times, Gansu was an important strategic outpost and communications link for the Chinese empire, as the Hexi Corridor runs along the "neck" of the province. The Han dynasty extended the Great Wall across this corridor, building the strategic Yumenguan (Jade Gate Pass, near Dunhuang) and Yangguan fort towns along it. Remains of the wall and the towns can be found there. The Ming dynasty built the Jiayuguan outpost in Gansu. To the west of Yumenguan and the Qilian Mountains, at the northwestern end of the province, the Yuezhi, Wusun, and other nomadic tribes dwelt (Shiji 123), occasionally figuring in regional imperial Chinese geopolitics.

By the Qingshui treaty, concluded in 823 between the Tibetan Empire and the Tang dynasty, China lost much of western Gansu province for a significant period.[9]

After the fall of the Uyghur Khaganate, a Buddhist Yugur (Uyghur) state called the Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom was established by migrating Uyghurs from the Khaganate in part of Gansu that lasted from 848 to 1036 AD.

Along the Silk Road, Gansu was an economically important province, as well as a cultural transmission path. Temples and Buddhist grottoes[10] such as those at Mogao Caves ('Caves of the Thousand Buddhas') and Maijishan Caves contain artistically and historically revealing murals.[11] An early form of paper inscribed with Chinese characters and dating to about 8 BC was discovered at the site of a Western Han garrison near the Yumen pass in August 2006.[12]

The Xixia or Western Xia dynasty controlled much of Gansu as well as Ningxia.

The province was also the origin of the Dungan Revolt of 1862–77. Among the Qing forces were Muslim generals, including Ma Zhan'ao and Ma Anliang, who helped the Qing crush the rebel Muslims. The revolt had spread into Gansu from neighbouring Qinghai.

There was another Dungan revolt from 1895 to 1896.

Republican China

As a result of frequent earthquakes, droughts and famines, the economic progress of Gansu was significantly slower than that of other provinces of China until recently. Based on the area's abundant mineral resources it has begun developing into a vital industrial center. An earthquake in Gansu at 8.6 on the Richter scale killed around 180,000 people mostly in the present-day area of Ningxia in 1920, and another with a magnitude of 7.6 killed 275 in 1932.[13]

The Muslim Conflict in Gansu (1927–1930) was a conflict against the Guominjun.

While the Muslim General Ma Hongbin was acting chairman of the province, Muslim General Ma Buqing was in virtual control of Gansu in 1940. Liangzhou District in Wuwei was previously his headquarters in Gansu, where he controlled 15 million Muslims.[14] Xinjiang came under Kuomintang (Nationalist) control after their soldiers entered via Gansu.[15] Gansu's Tienshui was the site of a Japanese-Chinese warplane fight.[16]

Gansu was vulnerable to Soviet penetration via Xinjiang.[17] Gansu was a passageway for Soviet supplies during the Second Sino-Japanese War.[18] Lanzhou was a destination point via a road coming from Dihua (Ürümqi).[19] Lanzhou and Lhasa were designated to be recipients of a new railway.[20]

The Kuomintang Islamic insurgency in China (1950–1958) was a prolongation of the Chinese Civil War in several provinces including Gansu.

Geography

Gansu has an area of 454,000 square kilometres (175,000 sq mi), and the vast majority of its land is more than 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) above sea level. It lies between the Tibetan Plateau and the Loess Plateau, bordering Mongolia (Govi-Altai Province) to the northwest, Inner Mongolia and Ningxia to the north, Shaanxi to the east, Sichuan to the south, and Xinjiang to the west. The Yellow River passes through the southern part of the province. The province contains the geographical centre of China, marked by the Center of the Country Monument at 35°50′40.9″N 103°27′7.5″E.[21]

Part of the Gobi Desert is located in Gansu, as well as small parts of the Badain Jaran Desert and the Tengger Desert.

The Yellow River gets most of its water from Gansu, flowing straight through Lanzhou. The area around Wuwei is part of Shiyang River Basin.[22]

The landscape in Gansu is very mountainous in the south and flat in the north. The mountains in the south are part of the Qilian Mountains, while the far western Altyn-Tagh contains the province's highest point, at 5,830 metres (19,130 ft).

A natural land passage known as Hexi Corridor, stretching some 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) from Lanzhou to the Jade Gate, is situated within the province. It is bound from north by the Gobi Desert and Qilian Mountains from the south.

Gansu generally has a semi-arid to arid continental climate (Köppen BSk or BWk) with warm to hot summers and cold to very cold winters, although diurnal temperature ranges are often so large that maxima remain above 0 °C (32 °F) even in winter. However, due to extreme altitude, some areas of Gansu exhibit a subarctic climate (Dwc) – with winter temperatures sometimes dropping to −40 °C (−40 °F). Most of the limited precipitation is delivered in the summer months: winters are so dry that snow cover is confined to very high altitudes and the snow line can be as high as 5,500 metres (18,040 ft) in the southwest.

.jpg) Qilian Mountains southeast of Jiuquan

Qilian Mountains southeast of Jiuquan Terrace farms near Tianshui

Terrace farms near Tianshui Grasslands in Min County

Grasslands in Min County Wetland by the Yellow River, Maqu County

Wetland by the Yellow River, Maqu County

Administrative divisions

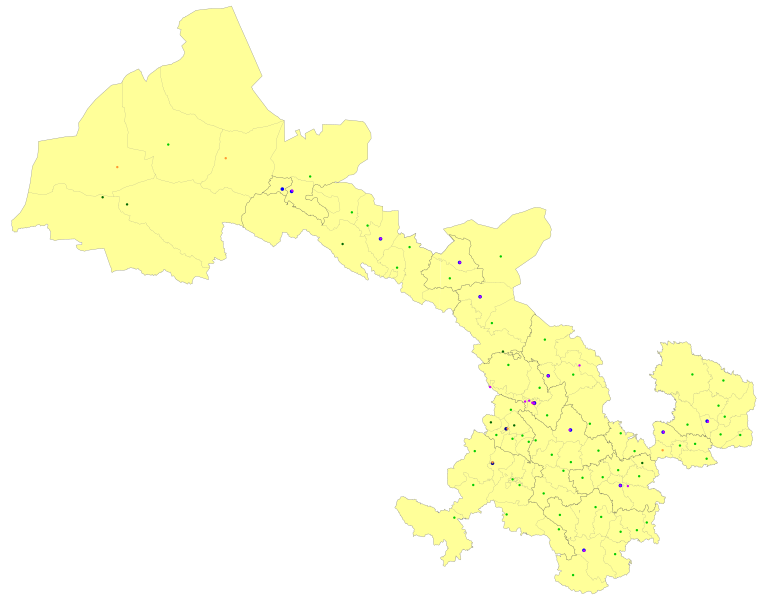

Gansu is divided into fourteen prefecture-level divisions: twelve prefecture-level cities and two autonomous prefectures:

| Administrative divisions of Gansu | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division code[23] | Division | Area in km2[24] | Population 2010[25] | Seat | Divisions[26] | ||||||

| Districts | Counties | Aut. counties | CL cities | ||||||||

| 620000 | Gansu Province | 425800.00 | 25,575,254 | Lanzhou city | 17 | 58 | 7 | 4 | |||

| 620100 | Lanzhou city | 13,103.04 | 3,616,163 | Chengguan District | 5 | 3 | |||||

| 620200 | Jiayuguan city* | 2,935.00 | 231,853 | Shengli Subdistrict | |||||||

| 620300 | Jinchang city | 7,568.84 | 464,050 | Jinchuan District | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 620400 | Baiyin city | 20,164.09 | 1,708,751 | Baiyin District | 2 | 3 | |||||

| 620500 | Tianshui city | 14,312.13 | 3,262,548 | Qinzhou District | 2 | 4 | 1 | ||||

| 620600 | Wuwei city | 32,516.91 | 1,815,054 | Liangzhou District | 1 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| 620700 | Zhangye city | 39,436.54 | 1,199,515 | Ganzhou District | 1 | 4 | 1 | ||||

| 620800 | Pingliang city | 11,196.71 | 2,068,033 | Kongtong District | 1 | 6 | |||||

| 620900 | Jiuquan city | 193,973.78 | 1,095,947 | Suzhou District | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 621000 | Qingyang city | 27,219.71 | 2,211,191 | Xifeng District | 1 | 7 | |||||

| 621100 | Dingxi city | 19,646.14 | 2,698,622 | Anding District | 1 | 6 | |||||

| 621200 | Longnan city | 27,856.69 | 2,567,718 | Wudu District | 1 | 8 | |||||

| 622900 | Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture | 8,116.57 | 1,946,677 | Linxia city | 5 | 2 | 1 | ||||

| 623000 | Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 38,311.56 | 689,132 | Hezuo city | 7 | 1 | |||||

| * – direct-piped cities – does not contain any county-level divisions | |||||||||||

| Administrative divisions in Chinese and varieties of romanizations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| English | Chinese | Pinyin | ||

| Gansu Province | 甘肃省 | Gānsù Shěng | ||

| Lanzhou city | 兰州市 | Lánzhōu Shì | ||

| Jiayuguan city | 嘉峪关市 | Jiāyùguān Shì | ||

| Jinchang city | 金昌市 | Jīnchāng Shì | ||

| Baiyin city | 白银市 | Báiyín Shì | ||

| Tianshui city | 天水市 | Tiānshuǐ Shì | ||

| Wuwei city | 武威市 | Wǔwēi Shì | ||

| Zhangye city | 张掖市 | Zhāngyè Shì | ||

| Pingliang city | 平凉市 | Píngliáng Shì | ||

| Jiuquan city | 酒泉市 | Jiǔquán Shì | ||

| Qingyang city | 庆阳市 | Qìngyáng Shì | ||

| Dingxi city | 定西市 | Dìngxī Shì | ||

| Longnan city | 陇南市 | Lǒngnán Shì | ||

| Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture | 临夏回族自治州 | Línxià Huízú Zìzhìzhōu | ||

| Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture | 甘南藏族自治州 | Gānnán Zàngzú Zìzhìzhōu | ||

The fourteen Prefecture of Gansu are subdivided into 82 county-level divisions (17 districts, 4 county-level cities, 58 counties, and 3 autonomous counties).

Urban areas

| Population by urban areas of prefecture & county cities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | City | Urban area[27] | District area[27] | City proper[27] | Census date |

| 1 | Lanzhou | 2,438,595 | 2,628,426 | 3,616,163 | 2010-11-01 |

| 2 | Tianshui | 544,441 | 1,197,174 | 3,262,549 | 2010-11-01 |

| 3 | Baiyin | 362,363 | 486,799 | 1,708,752 | 2010-11-01 |

| 4 | Wuwei | 331,370 | 1,010,295 | 1,815,059 | 2010-11-01 |

| 5 | Jiuquan | 255,739 | 428,346 | 1,095,947 | 2010-11-01 |

| 6 | Pingliang | 248,421 | 504,848 | 2,068,033 | 2010-11-01 |

| 7 | Linxia | 220,895 | 274,466 | part of Linxia Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

| 8 | Zhangye | 216,760 | 507,433 | 1,199,515 | 2010-11-01 |

| 9 | Jiayuguan | 216,362 | 231,853 | 231,853 | 2010-11-01 |

| 10 | Jinchang | 195,409 | 228,561 | 464,050 | 2010-11-01 |

| 11 | Qingyang | 181,780 | 377,528 | 2,211,191 | 2010-11-01 |

| 12 | Dingxi | 158,062 | 420,614 | 2,698,624 | 2010-11-01 |

| 13 | Longnan | 136,468 | 555,004 | 2,567,718 | 2010-11-01 |

| 14 | Dunhuang | 111,535 | 186,027 | see Jiuquan | 2010-11-01 |

| (15) | Huating[lower-alpha 1] | 88,454 | 189,333 | see Pingliang | 2010-11-01 |

| 16 | Yumen | 78,940 | 159,792 | see Jiuquan | 2010-11-01 |

| 17 | Hezuo | 57,384 | 90,290 | see Gannan Prefecture | 2010-11-01 |

- Huating County is currently known as Huating CLC after census.

Politics

Secretaries of the CPC Gansu Committee: The Secretary of the CPC Gansu Committee is the highest-ranking office within Gansu Province.[28]

- Zhang Desheng (张德生): 1949–1954

- Zhang Zhongliang (张仲良): 1954–1961

- Wang Feng (汪锋): 1961–1966

- Hu Jizong (胡继宗): 1966–1967

- Xian Henghan (冼恒汉): 1970–1977

- Song Ping (宋平): 1977–1981

- Feng Jixin (冯纪新): 1981–1983

- Li Ziqi (李子奇): 1983–1990

- Gu Jinchi (顾金池): 1990–1993

- Yan Haiwang (阎海旺): 1993–1998

- Sun Ying (孙英): 1998–2001

- Song Zhaosu (宋照肃): 2001–2003

- Su Rong (苏荣): 2003–2007

- Lu Hao (陆浩): April 2007 − December 2011

- Wang Sanyun (王三运): December 2011 − March 2017

- Lin Duo (林铎): March 2017 − incumbent

Governors of Gansu: The Governorship of Gansu is the second highest-ranking official within Gansu, behind the Secretary of the CPC Gansu Committee.[28] The governor is responsible for all issues related to economics, personnel, political initiatives, the environment and the foreign affairs of the province.[28] The Governor is appointed by the Gansu Provincial People's Congress, which is the province's legislative body.[28]

- Wang Shitai (王世泰): 1949–1950

- Deng Baoshan (邓宝姗): 1950–1967

- Xian Henghan (冼恒汉): 1967–1977

- Song Ping (宋平): 1977–1979

- Feng Jixin (冯纪新): 1979–1981

- Li Dengying (李登瀛): 1981–1983

- Chen Guangyi (陈光毅): 1983–1986

- Jia Zhijie (贾志杰): 1986–1993

- Yan Haiwang (阎海旺): 1993

- Zhang Wule (张吾乐): 1993–1996

- Sun Ying (孙英): 1996–1998

- Song Zhaosu (宋照肃): 1998–2001

- Lu Hao (陆浩): 2001–2006

- Xu Shousheng (徐守盛): January 2007 – July 2010[28]

- Liu Weiping (刘伟平): July 2010 – April 2016

- Lin Duo (林铎): April 2016 – April 2017

- Tang Renjian (唐仁健): April 2017−incumbent

Economy

Agricultural production includes cotton, linseed oil, maize, melons (such as the honeydew melon, known locally as the Bailan melon or "Wallace" due to its introduction by US vice president Henry A. Wallace),[29] millet, and wheat. Gansu is known as a source for wild medicinal herbs which are used in Chinese medicine. However, pollution by heavy metals, such as cadmium in irrigation water, has resulted in the poisoning of many acres of agricultural land. The extent and nature of the heavy metal pollution is considered a state secret.[30]

However, most of Gansu's economy is based on mining and the extraction of minerals, especially rare earth elements. The province has significant deposits of antimony, chromium, coal, cobalt, copper, fluorite, gypsum, iridium, iron, lead, limestone, mercury, mirabilite, nickel, crude oil, platinum, troilite, tungsten, and zinc among others. The oil fields at Yumen and Changqing are considered significant.

Gansu has China's largest nickel deposits accounting for over 90% of China's total nickel reserves.

Industries other than mining include electricity generation, petrochemicals, oil exploration machinery, and building materials.

According to some sources, the province is also a center of China's nuclear industry.

Despite recent growth in Gansu and the booming economy in the rest of China, Gansu is still considered to be one of the poorest provinces in China. Its nominal GDP for 2017 was about 767.7 billion yuan (US$113.70 billion) and per capita of 29,326 RMB (US$4,343). Tourism has been a bright spot in contributing to Gansu's overall economy. As mentioned below, Gansu offers a wide variety of choices for national and international tourists.

As stipulated in the country's 12th Five Year Plan, the local government of Gansu hopes to grow the province's GDP by 10% annually by focusing investments on five pillar industries: renewable energy, coal, chemicals, nonferrous metals, pharmaceuticals and services.

Economic and technological development zones

The following economic and technological zones are situated in Gansu:

- Lanzhou National Economic and Technological Development Zone was established in 1993, located in the center of Lanzhou Anning District. The zone has a planned area of 9.53 km2 (3.68 sq mi). 17 colleges, 11 scientific research institutions, 21 large and medium-size companies and other 1735 enterprises have been set up in the zone. Main industries include textile mills, rubber, fertilizer plants, oil refinery, petrochemical, machinery, and metallurgical industry.[31]

- Lanzhou New & Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone, Lanzhou Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone, one of the first 27 national hi-tech industrial development zones, was established in 1998 covering more than 10 km2 (3.9 sq mi). It is expected to expand another 19 km2 (7.3 sq mi). The zone mainly focuses on Biotechnology, chemical industry, building decoration materials and information technology.[32]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1912[33] | 4,990,000 | — |

| 1928[34] | 6,281,000 | +25.9% |

| 1936–37[35] | 6,716,000 | +6.9% |

| 1947[36] | 7,091,000 | +5.6% |

| 1954[37] | 12,928,102 | +82.3% |

| 1964[38] | 12,630,569 | −2.3% |

| 1982[39] | 19,569,261 | +54.9% |

| 1990[40] | 22,371,141 | +14.3% |

| 2000[41] | 25,124,282 | +12.3% |

| 2010[42] | 25,575,254 | +1.8% |

| Ningxia Province/AR was part of Gansu Province until 1929 and 1954–1958. | ||

Gansu province is home to 30,711,287 people. 73% of the population is rural. Gansu is 92% Han and also has Hui, Tibetan, Dongxiang, Tu, Yugur, Bonan, Mongolian, Salar, and Kazakh minorities. Gansu province's community of Chinese Hui Muslims was bolstered by Hui Muslims resettled from Shaanxi province during the Dungan Revolt. Gansu is also a historical home, along with Shaanxi, of the dialect of the Dungans, who migrated to Central Asia. The southwestern corner of Gansu is home to a large ethnic Tibetan population.

Languages

Most of the inhabitants of Gansu speak dialects of Northern Mandarin Chinese. On the border areas of Gansu one might encounter Tu, Amdo Tibetan, Mongolian, and the Kazakh language. Most of the minorities also speak Chinese.

Culture

The cuisine of Gansu is based on the staple crops grown there: wheat, barley, millet, beans, and sweet potatoes. Within China, Gansu is known for its lamian (pulled noodles), and Muslim restaurants which feature authentic Gansu cuisine.

Religion

According to a 2012 survey[43] only around 12% of the population of Gansu belongs to organised religions, the largest groups being Buddhists with 8.2%, followed by Muslims with 3.4%, Protestants with 0.4% and Catholic with 0.1% (in total, as of 2012 Christians comprise 0.5% of the population, decreasing from 1.02% in 2004[44]) Around 88% of the population may be either irreligious or involved in worship of nature deities, Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, and folk religious sects.

Muslim restaurants are known as "qingzhen restaurants" ("pure truth restaurants"), and feature typical Chinese dishes, but without any pork products, and instead an emphasis on lamb and mutton. Gansu has many works of Buddhist art, including the Maijishan Grottoes. Dunhuang was a major centre of Buddhism in the Middle Ages.

|

Tourism

.jpg)

Jiayuguan Pass of the Great Wall

Jiayuguan Pass, in Jiayuguan city, is the largest and most intact pass, or entrance, of the Great Wall. Jiayuguan Pass was built in the early Ming dynasty, somewhere around the year 1372. It was built near an oasis that was then on the extreme western edge of China. Jiayuguan Pass was the first pass on the west end of the great wall so it earned the name "The First And Greatest Pass Under Heaven".

An extra brick is said to rest on a ledge over one of the gates. One legend holds that the official in charge asked the designer to calculate how many bricks would be used. The designer gave him the number and when the project was finished, only one brick was left. It was put on the top of the pass as a symbol of commemoration. Another account holds that the building project was assigned to a military manager and an architect. The architect presented the manager with a requisition for the total number of bricks that he would need. When the manager found out that the architect had not asked for any extra bricks, he demanded that the architect make some provision for unforeseen circumstances. The architect, taking this as an insult to his planning ability, added a single extra brick to the request. When the gate was finished, the single extra brick was, in fact, extra and was left on the ledge over the gate.[46]

Mogao Grottoes

The Mogao Grottoes near Dunhuang have a collection of Buddhist art. Originally there were a thousand grottoes, but now only 492 cave temples remain. Each temple has a large statue of a buddha or bodhisattva and paintings of religious scenes. In 336 AD, a monk named Le Zun (Lo-tsun) came near Echoing Sand Mountain, when he had a vision. He started to carve the first grotto. During the Five Dynasties period they ran out of room on the cliff and could not build any more grottoes.

Silk Road and Dunhuang City

The historic Silk Road starts in Chang'an and goes to Constantinople. On the way merchants would go to Dunhuang in Gansu. In Dunhuang they would get fresh camels, food and guards for the journey around the dangerous Taklamakan Desert. Before departing Dunhuang they would pray to the Mogao Grottoes for a safe journey, if they came back alive they would thank the gods at the grottoes. Across the desert they would form a train of camels to protect themselves from thieving bandits. The next stop, Kashi (Kashgar), was a welcome sight to the merchants. At Kashi most would trade and go back and the ones who stayed would eat fruit and trade their Bactrian camels for single humped ones. After Kashi they would keep going until they reached their next destination.

Located about 5 km (3.1 mi) southwest of the city, the Crescent Lake or Yueyaquan is an oasis and popular spot for tourists seeking respite from the heat of the desert. Activities includes camel and 4x4 rides.

Silk Route Museum

The Silk Route Museum is located in Jiuquan along the Silk Road, a trading route connecting Rome to China, used by Marco Polo. It is also built over the tomb of the Western Liang King.[47]

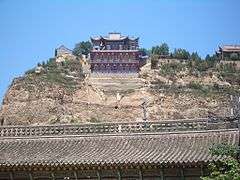

Bingling Temple

Bingling Temple, or Bingling Grottoes, is a Buddhist cave complex in a canyon along the Yellow River. Begun in 420 AD during the Jin dynasty, the site contains dozens of caves and caverns filled with outstanding examples of carvings, sculpture, and frescoes. The great Maitreya Buddha is more than 27 meters tall and is similar in style to the great Buddhas that once lined the cliffs of Bamiyan, Afghanistan. Access to the site is by boat from Yongjing in the summer or fall. There is no other access point.

Labrang Monastery

Labrang Tashikyil Monastery is located in Xiahe County, Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, located in the southern part of Gansu, and part of the traditional Tibetan province of Amdo. It is one of the six major monasteries of the Gelukpa tradition of Tibetan Buddhism in Tibet, and the most important one in Amdo. Built in 1710, it is headed by the Jamyang-zhaypa. It has 6 dratsang (colleges), and houses over sixty thousand religious texts and other works of literature as well as other cultural artifacts.

Education

Colleges and universities

- Lanzhou University, Lanzhou (兰州大学)

- Northwest Normal University, Lanzhou (西北师范大学)

- Lanzhou University of Technology, Lanzhou (兰州理工大学)

- Lanzhou Jiaotong University, Lanzhou (兰州交通大学)

- Northwest University of Nationalities, Lanzhou (西北民族大学)

- Gansu Agricultural University, Lanzhou (甘肃农业大学)

- Lanzhou City University, Lanzhou (兰州城市学院)

- Gansu Political Science and Law Institute, Lanzhou (甘肃政法学院)

- Gansu University of Technology

- Lanzhou Commercial College

- Lanzhou Polytechnic College

- Northwest Minority University

- Tianshui Normal College (Tianshui)

- Longdong College (Qingyang)

Natural resources

Land

- 166,400 square kilometres (64,200 sq mi) grassland

- 46,700 square kilometres (18,000 sq mi) mountain slopes suitable for livestock breeding

- 46,200 square kilometres (17,800 sq mi) forests (standing timber reserves of 0.2 cubic kilometres (0.048 cu mi))

- 35,300 square kilometres (13,600 sq mi) cultivated land (1,400 square metres (15,000 sq ft) per capita)

- 66,600 square kilometres (25,700 sq mi) wasteland suitable for forestation

- 10,000 square kilometres (3,900 sq mi) wasteland suitable for farming

Minerals

Three thousand deposits of 145 different minerals. Ninety-four minerals have been found and ascertained, including nickel, cobalt, platinum, selenium, casting clay, finishing serpentine, whose reserves are the largest in China. Gansu has advantages in getting nickel, zinc, cobalt, platinum, iridium, copper, barite, and baudisserite.

Energy

Among Gansu's most important sources of energy are its water resources: the Yellow River and other inland river drainage basins. Gansu is placed ninth among China's provinces in annual hydropower potential and water discharge. Gansu produces 17.24 gigawatts of hydropower a year. Twenty-nine hydropower stations have been constructed in Gansu, altogether(?) capable of generating 30 gigawatts. Gansu has an estimated coal reserve of 8.92 billion tons and petroleum reserve of 700 million tons.

There is also good potential for wind and solar power development. The Gansu Wind Farm project – already producing 7.965GW in 2015[48] – is expected to achieve 20GW by 2020, at which time it will likely become the world's biggest collective windfarm.

In November 2017 an agreement between the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Gansu government was announced, to site and begin operations of a molten salt reactor pilot project in the province by 2020.[49]

Flora and fauna

Gansu has 659 species of wild animals.[50] It has twenty-four rare animals which are under a state protection.

Gansu's mammals include some of the world's most charismatic: the giant panda, golden monkeys, lynx, snow leopards, sika deer, musk deer, and the Bactrian camel.

Among zoologists who study moles, the Gansu mole is of great interest. For a reason that can only be speculated, it is taxologically a New World mole living among Old World moles: that is to say, an American mole living in a sea of Euro-Asians.

Gansu is home to 441 species of birds; it is a center of endemism and home to many species and subspecies which occur nowhere else in the world.

Gansu is China's second-largest producer of medicinal plants and herbs, including some produced nowhere else, such as the hairy asiabell root, fritillary bulb, and Chinese caterpillar fungus.

Environment

Natural disasters

On 16 December 1920, Gansu witnessed the deadliest landslide ever recorded. A series of landslides, triggered by a single earthquake, accounted for most of the 180,000 people killed in the event.[51]

Anti-desertification project

The Asian Development Bank is working with the State Forestry Administration of China on the Silk Road Ecosystem Restoration Project, designed to prevent degradation and desertification in Gansu. It is estimated to cost up to US$150 million.

Space launch center

The Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center, located in the Gobi desert, is named after the city of Jiuquan, Gansu, the nearest city, although the center itself is in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.

See also

References

- "Communiqué of the National Bureau of Statistics of People's Republic of China on Major Figures of the 2010 Population Census [1] (No. 2)". National Bureau of Statistics of China. 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- 甘肃省2017年国民经济和社会发展统计公报 [Statistical Communiqué of Gansu Province on the 2017 National Economic and Social Development] (in Chinese). Statistical Bureau of Gansu. 18 April 2018. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- "Sub-national HDI - Subnational HDI - Global Data Lab". globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 17 April 2020.

- 1957–, Powers, John (2017). The Buddha party: how the people's Republic of China works to define and control Tibetan Buddhism. New York. pp. Appendix B, page 6. ISBN 9780199358151. OCLC 947145370.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Dadiwan Relics Break Archeological Records

- Xinhua – English Archived 5 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- People's Daily Online – Chinese surname history: Qin

- Over 2,200-Year-old Map Discovered in NW China Archived 12 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Turghun Almas, "Uygurlar", Kashgar, 1989.

- English.people.com.cn

- "Artistic treasures of Maiji Mountain caves" by Alok Shrotriya and Zhou Xue-ying. Asianart.com

- Xinhuanet.com

- NGDC. "Comments for the Significant Earthquake". Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- Harrison Forman (19 July 1942). "Moslem War Lord Isolated by China; Ma Pu-ching Sent to Swamps of Tibet With the Title of Reclamation Commissioner Member of a Noted Clan Vital Route to Russia Passes Through Area With 15,000,000 Believers in the Koran". The New York Times.

- Hsiao-ting Lin (13 September 2010). Modern China's Ethnic Frontiers: A Journey to the West. Routledge. pp. 76–. ISBN 978-1-136-92393-7.

- Alan Armstrong (2006). Preemptive Strike: The Secret Plan that Would Have Prevented the Attack on Pearl Harbor. Lyons Press. pp. 122–. ISBN 978-1-59228-913-4.

airfield kansu.

- Peter Fleming (19 August 2014). News from Tartary: An Epic Journey Across Central Asia. I.B.Tauris. pp. 264–. ISBN 978-0-85773-495-2.

- Andrew D. W. Forbes (9 October 1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: A Political History of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. CUP Archive. pp. 146–. ISBN 978-0-521-25514-1.

- Tetsuya Kataoka (1974). Resistance and Revolution in China: The Communists and the Second United Front. University of California Press. pp. 170–. ISBN 978-0-520-02553-0.

airfield kansu.

- Ginsburgs (11 November 2013). Communist China and Tibet: The First Dozen Years. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 100–. ISBN 978-94-017-5057-8.

- English.people.com.cn

- FutureWater. "Groundwater Management Exploration Package". # Wageningen, Netherlands. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2009.

- 中华人民共和国县以上行政区划代码 (in Chinese). Ministry of Civil Affairs.

- Shenzhen Bureau of Statistics. 《深圳统计年鉴2014》 (in Chinese). China Statistics Print. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Census Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China; Population and Employment Statistics Division of the National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China (2012). 中国2010年人口普查分乡、镇、街道资料 (1 ed.). Beijing: China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-6660-2.

- Ministry of Civil Affairs (August 2014). 《中国民政统计年鉴2014》 (in Chinese). China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-7130-9.

- 国务院人口普查办公室、国家统计局人口和社会科技统计司编 (2012). 中国2010年人口普查分县资料. Beijing: China Statistics Print. ISBN 978-7-5037-6659-6.

- "Xu Shousheng re-elected governor of northwest China's Gansu Province". Xinhua. 27 January 2008. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- Hudong.com This simplified Chinese page discusses how the seeds were brought to China, the connection to Wallace, dates, etc.

- Liu Hongqiao (1 March 2013). "The Poison Eaters of Gansu Province: Pollution is not a problem some western farmers can choose to ignore, as many say they have suffered from chronic bone pains for decades". Caixin. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- RightSite.asia Archived 11 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Lanzhou Economic and Technological Development Zone

- RightSite.asia Archived 17 July 2012 at Archive.today, Lanzhou Hi-Tech Industrial Development Zone

- 1912年中国人口. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- 1928年中国人口. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- 1936–37年中国人口. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- 1947年全国人口. Retrieved 6 March 2014.

- 中华人民共和国国家统计局关于第一次全国人口调查登记结果的公报. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on 5 August 2009.

- 第二次全国人口普查结果的几项主要统计数字. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012.

- 中华人民共和国国家统计局关于一九八二年人口普查主要数字的公报. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012.

- 中华人民共和国国家统计局关于一九九〇年人口普查主要数据的公报. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on 19 June 2012.

- 现将2000年第五次全国人口普查快速汇总的人口地区分布数据公布如下. National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on 29 August 2012.

- "Communiqué of the National Bureau of Statistics of People's Republic of China on Major Figures of the 2010 Population Census". National Bureau of Statistics of China. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013.

- 当代中国宗教状况报告——基于CFPS(2012)调查数据 [China Family Panel Studies 2012] (PDF) (in Chinese). Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014.. p. 013

- China General Social Survey 2009, Chinese Spiritual Life Survey (CSLS) 2007. Report by: Xiuhua Wang (2015, p. 15) Archived 25 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Wang Xudang, Li Zuixiong, and Zhang Lu (2010). "Condition, Conservation, and Reinforcement of the Yumen Pass and Hecang Earthen Ruins Near Dunhuang", in Neville Agnew (ed), Conservation of Ancient Sites on the Silk Road: Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Conservation of Grotto Sites, Mogao Grottoes, Dunhuang, People's Republic of China, 28 June – 3 July 2004, 351–357. Los Angeles: The Getty Conservation Institute, J. Paul Getty Trust. ISBN 978-1-60606-013-1, pp 351–352.

- "The Great Wall in Gansu". Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- Silk Route Museum China Tourist Information Tourist Link.

- "South Africa's biggest wind farms vs the world". BusinessTech. 22 July 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- 中科院与甘肃省签署钍基熔盐堆核能系统项目战略合作框架协议----中国科学院. Chinese Academy of Sciences. 10 November 2017.

- Gansu.gov.cn Archived 15 November 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Glenday, Craig (2013). Guinness world records 2014. The Jim Pattison Group. pp. 015. ISBN 978-1-908843-15-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gansu. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Gansu. |

- Gansu Government official website

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.