Gore-Tex

Gore-Tex is a waterproof, breathable fabric membrane and registered trademark of W. L. Gore and Associates. Invented in 1969, Gore-Tex can repel liquid water while allowing water vapor to pass through and is designed to be a lightweight, waterproof fabric for all-weather use. It is composed of stretched polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), which is more commonly known by the generic trademark Teflon. The material is formally known as the generic term expanded PTFE (ePTFE).

History

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

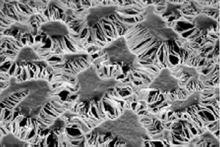

Gore-Tex was co-invented by Wilbert L. Gore and Gore's son, Robert W. Gore.[1] In 1969, Bob Gore stretched heated rods of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) and created expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE). His discovery of the right conditions for stretching PTFE was a happy accident, born partly of frustration. Instead of slowly stretching the heated material, he applied a sudden, accelerating yank. The solid PTFE unexpectedly stretched about 800%, forming a microporous structure that was about 70% air.[1] It was introduced to the public under the trademark Gore-Tex.[2]

Gore promptly applied for and obtained the following patents:

- U.S. Patent 3,953,566, issued April 27, 1976, for a porous form of polytetrafluoroethylene with a micro-structure characterized by nodes interconnected by fibrils

- U.S. Patent 4,187,390, issued February 5, 1980

- U.S. Patent 4,194,041 on March 18, 1980 for a "waterproof laminate", together with Samuel Allen

Another form of stretched PTFE tape was produced prior to Gore-Tex in 1966, by John W. Cropper of New Zealand. Cropper had developed and constructed a machine for this use. However, Cropper chose to keep the process of creating expanded PTFE as a closely held trade secret and as such, it had remained unpublished.[3][4]

In the 1970s Garlock, Inc. allegedly infringed Gore's patents by using Cropper's machine and was sued by Gore in the Federal District Court of Ohio. The District Court held Gore's product and process patents to be invalid after a "bitterly contested case" that "involved over two years of discovery, five weeks of trial, the testimony of 35 witnesses (19 live, 16 by deposition), and over 300 exhibits" (quoting the Federal Circuit). On appeal, however, the Federal Circuit disagreed in the famous case of Gore v. Garlock, reversing the lower court's decision on the ground, as well as others, that Cropper forfeited any superior claim to the invention by virtue of having concealed the process for making ePTFE from the public. As a public patent had not been filed, the new form of the material could not be legally recognised. Gore was thereby established as the legal inventor of ePTFE.[3][5]

Following the Gore v. Garlock decision, Gore sued C. R. Bard for allegedly infringing its patent by making ePTFE vascular grafts. Bard promptly settled and agreed to exit the market. Gore next sued IMPRA, Inc., a smaller maker of ePTFE vascular grafts, in the federal district court in Arizona. IMPRA had a competing patent application for the ePTFE vascular graft. In a nearly decade-long patent/antitrust battle (1984–1993), IMPRA proved that Gore-Tex was identical to prior art disclosed in a Japanese process patent by duplicating the prior art process and through statistical analysis, and also proved that Gore had withheld the best mode for using its patent, and the main claim of Gore's product patent was declared invalid in 1990.[6] In 1996, IMPRA was purchased by Bard and Bard was thereby able to reenter the market. After IMPRA's vascular graft patent was issued, Bard sued Gore for infringing it.

Gore-Tex is used in products manufactured by many different companies.

Other products have come to market exploiting similar technologies following the expiry of the main Gore-Tex patent.[7]

For his invention, Robert W. Gore was inducted into the U.S. National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2006.[8]

In 2015, Gore was ordered by the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals to pay Bard $1 billion in damages.[6] The U.S. Supreme Court declined to review the Federal Circuit's decision.[9][10]

Manufacture

PTFE is made using an emulsion polymerization process that utilizes the fluorosurfactant PFOA,[11][12] a persistent environmental contaminant. In 2013, Gore eliminated the use of PFOAs in the manufacture of its weatherproof functional fabrics.[13]

Design

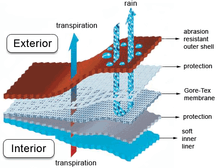

Gore-Tex materials are typically based on thermo-mechanically expanded PTFE and other fluoropolymer products. They are used in a wide variety of applications such as high-performance fabrics, medical implants, filter media, insulation for wires and cables, gaskets, and sealants. However, Gore-Tex fabric is best known for its use in protective, yet breathable, rainwear.

The simplest sort of rain wear is a two layer sandwich. The outer layer is typically nylon or polyester and provides strength. The inner one is polyurethane (abbreviated: PU), and provides water resistance, at the cost of breathability.

Early Gore-Tex fabric replaced the inner layer of PU with a thin, porous fluoropolymer membrane (Teflon) coating that is bonded to a fabric. This membrane had about 9 billion pores per square inch (around 1.4 billion pores per square centimeter). Each pore is approximately 1⁄20,000 the size of a water droplet, making it impenetrable to liquid water while still allowing the more volatile water vapour molecules to pass through.

The outer layer of Gore-Tex fabric is coated on the outside with a Durable Water Repellent (DWR) treatment. The DWR prevents the main outer layer from becoming wet, which would reduce the breathability of the whole fabric. However, the DWR is not responsible for the jacket being waterproof. Without the DWR, the outer layer would become soaked, there would be no breathability, and the wearer's sweat being produced on the inside would fail to evaporate, leading to dampness there. This might give the appearance that the fabric is leaking, but it is not. Wear and cleaning will reduce the performance of Gore-Tex fabric by wearing away this Durable Water Repellent (DWR) treatment. The DWR can be reinvigorated by tumble drying the garment or ironing on a low setting.[14]

Gore requires that all garments made from their material have taping over the seams, to eliminate leaks. Gore's sister product, Windstopper, is similar to Gore-Tex in being windproof and breathable and it can stretch but it is not waterproof. The Gore naming system does not imply specific technology or material but instead specific set of performance characteristics.[15]

Clothing technology and lifestyle

Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene is used in clothing due to its breathability and water protection capabilities. It is used in rain jackets, and ePTFE can now be found in space suits and heart patches.[16]

Gore-Tex Armacor® product technology

Some waterproof Gore-Tex Pro garments for motorcycling contain Armacor (made from 700D Cordura, plus Kevlar every fourth thread). Gore claims that Armacor offers increased tear and abrasion resistance – while still being light in weight and allowing mobility.[17] Independent testing by Austria’s Motorcycle Clothing Assessment Program (MotoCAP) supports this assertion.

In Motorcycle personal protective equipment, Armacor competes against SuperFabric. MotoCAP has tested garments with Armacor and SuperFabric.[18] It found Armacor typically provided just 2 seconds of abrasion resistance; while SuperFabric (as used by Klim) provided about 4 seconds abrasion resistance. Both materials were significantly more protective than non-reinforced Gore-Tex Pro (only 0.69 seconds of abrasion resistance).

Other uses

Gore-Tex is also used internally in medical applications, because it is nearly inert inside the body. Specifically, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (E-PTFE) can undergo the form of a fabric-like mesh. Implementing and applying the mesh form in the medical field is a promising type of technological material feature.[19] In addition, the porosity of Gore-Tex permits the body's own tissue to grow through the material, integrating grafted material into the circulation system.[20] Gore-Tex is used in a wide variety of medical applications, including sutures, vascular grafts, heart patches, and synthetic knee ligaments, which have saved thousands of lives.[21] In the form of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (E-PTFE), Gore-Tex has been shown to be a reliable synthetic, medical material in treating patients with nasal dorsal interruptions.[22] In more recent observations, expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (E-PTFE) has recently been used as membrane implants for glaucoma surgery.[23]

Gore-Tex has been used for many years in the conservation of illuminated manuscripts.[24]

Explosive sensors have been printed on Gore-Tex clothing leading to the sensitive voltametric detection of nitroaromatic compounds.[25]

Gore-Tex is also used as a membrane in sealed battery products, to allow pressure relief from outgassing, but preventing ingress of moisture.

The "Gore-Tex" brand name was formerly used for industrial and medical products.[26][27]

Gore-Tex membrane under an electron microscope

Gore-Tex membrane under an electron microscope Gore-Tex Medical Devices Sample Kit, Science History Institute

Gore-Tex Medical Devices Sample Kit, Science History Institute

References

- "Robert W. Gore". Science History Institute. Retrieved March 20, 2018.

- Clough, Norman E. "Innovations in ePTFE Fiber Technology" (PDF). W. L. Gore & Associates, Inc.

- W. L. Gore Associates v. Garlock, Inc, 721 F.2d 1540. 220 U.S.P.Q. 303 (Fed. Cir. 1983).

- Schechter, Roger; Thomas, John (2008). "16.3.2.8 First Inventor Defense". Schechter and Thomas' Intellectual Property: The Law of Copyrights, Patents and Trademarks (Hornbook Series). West Academic. ISBN 9781628105186.

- Bridges, Jon (September 2014). No 8 Rewired: 202 New Zealand Inventions that Changed the World. Penguin Group. ISBN 9780143571957.

- "Bard Peripheral Vascular, Inc. v. W.L. Gore & Assocs., Inc., No. 14-1114 (Fed. Cir. 2015)". Justia Law. Justia. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- Logue, Victoria. (2005). Hiking and Backpacking. Menasha Ridge Press. p. 74. ISBN 0-89732-584-2.

- "Robert W. Gore". National Inventors Hall of Fame. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- "W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc., Petitioner v.Bard Peripheral Vascular, Inc., et al., No. 15-41". SCOTUSblog. United States Supreme Court. October 5, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- "Docket for No. 15-41, W.L. Gore & Associates, Inc., Petitioner v. Bard Peripheral Vascular, Inc., et al." (TEXT). www.supremecourt.gov. United States Supreme Court. October 5, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2017.

- Lehmler, HJ (2005). "Synthesis of environmentally relevant fluorinated surfactants—a review". Chemosphere. 58 (11): 1471–96. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.11.078. PMID 15694468.

- Lau C, Anitole K, Hodes C, Lai D, Pfahles-Hutchens A, Seed J (2007). "Perfluoroalkyl acids: a review of monitoring and toxicological findings". Toxicol. Sci. 99 (2): 366–94. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfm128. PMID 17519394.

- "GORE completes elimination of PFOA from raw material of its functional fabrics" (Press release). W. L. Gore & Associates. January 10, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- "Care Centre". W. L. Gore & Associates. Archived from the original on July 10, 2010. Retrieved January 20, 2011.

- "Fall 2008 Fabrics and Technologies". Ames Adventure Outfitters. October 18, 2007. Archived from the original on July 11, 2011.

- Keats, Jonathon. "The Accidental Origins of an Outdoor Clothing Essential". Wired. Wired, Conde Nast. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- https://www.gore-tex.com/technology/original-gore-tex-products/pro

- https://motocap.com.au/

- Simonovsky, Felix. "Biomaterials Tutorial Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)". University of Washington Engineered Biomaterials. University of Washington Engineered Biomaterials. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

- Bowden, Mary Ellen. "The Cyborg Transformed". Chemical Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on July 12, 2016. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- "Wilbert L. "Bill" Gore". Plastics Academy Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- Lohuis, P.J.F.M.; Watts, S.J.; Vuyk, H.D. (2001). "Augmentation of the nasal dorsum using Gore‐Tex®: intermediate results of a retrospective analysis of experience in 66 patients". Clinical Otolaryngology and Allied Sciences. 26 (3): 214–217. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2273.2001.00453.x.

- Wang X, Khan R, Coleman A (2015). "Device-modified trabeculectomy for glaucoma". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12: CD010472. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010472.pub2. PMC 4715269. PMID 26625212.

- Singer, Hannah (1992). "The Conservation of Parchment Objects Using Gore-Tex Laminate". The Paper Conservator. 16: 40. doi:10.1080/03094227.1992.9638574.

- Chuang, Min-Chieh; Windmiller, Joshua Ray; Santhosh, Padmanabhan; Ramírez, Gabriela Valdés; Galik, Michal; Chou, Tzu-Yang; Wang, Joseph (2010). "Textile-based Electrochemical Sensing: Effect of Fabric Substrate and Detection of Nitroaromatic Explosives". Electroanalysis. 22 (21): 2511. doi:10.1002/elan.201000434.

- Roolker, W.; Patt, T. W.; Van Dijk, C. N.; Vegter, M.; Marti, R. K. (2000). "The Gore-Tex prosthetic ligament as a salvage procedure in deficient knees". Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 8: 20. doi:10.1007/s001670050005.

- Grethel, EJ; Cortes, RA; Wagner, AJ; Clifton, MS; Lee, H; Farmer, DL; Harrison, MR; Keller, RL; Nobuhara, KK (2006). "Prosthetic patches for congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair: Surgisis vs Gore-Tex". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 41 (1): 29–33, discussion 29–33. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2005.10.005. PMID 16410103.

.svg.png)