Spread spectrum

In telecommunication and radio communication, spread-spectrum techniques are methods by which a signal (e.g., an electrical, electromagnetic, or acoustic signal) generated with a particular bandwidth is deliberately spread in the frequency domain, resulting in a signal with a wider bandwidth. These techniques are used for a variety of reasons, including the establishment of secure communications, increasing resistance to natural interference, noise, and jamming, to prevent detection, to limit power flux density (e.g., in satellite down links), and to enable multiple-access communications.

| Passband modulation |

|---|

| Analog modulation |

| Digital modulation |

| Hierarchical modulation |

| Spread spectrum |

| See also |

|

| Multiplexing |

|---|

|

| Analog modulation |

|

Statistical multiplexing (variable bandwidth) |

|

| Related topics |

| Part of a series on |

| Antennas |

|---|

|

|

Common types |

|

Safety and regulation

|

|

Radiation sources / regions

|

Telecommunications

Spread spectrum generally makes use of a sequential noise-like signal structure to spread the normally narrowband information signal over a relatively wideband (radio) band of frequencies. The receiver correlates the received signals to retrieve the original information signal. Originally there were two motivations: either to resist enemy efforts to jam the communications (anti-jam, or AJ), or to hide the fact that communication was even taking place, sometimes called low probability of intercept (LPI).[1]

Frequency-hopping spread spectrum (FHSS), direct-sequence spread spectrum (DSSS), time-hopping spread spectrum (THSS), chirp spread spectrum (CSS), and combinations of these techniques are forms of spread spectrum. The first two of these techniques employ pseudorandom number sequences—created using pseudorandom number generators—to determine and control the spreading pattern of the signal across the allocated bandwidth. Wireless standard IEEE 802.11 uses either FHSS or DSSS in its radio interface.

- Techniques known since the 1940s and used in military communication systems since the 1950s "spread" a radio signal over a wide frequency range several magnitudes higher than minimum requirement. The core principle of spread spectrum is the use of noise-like carrier waves, and, as the name implies, bandwidths much wider than that required for simple point-to-point communication at the same data rate.

- Resistance to jamming (interference). Direct sequence (DS) is good at resisting continuous-time narrowband jamming, while frequency hopping (FH) is better at resisting pulse jamming. In DS systems, narrowband jamming affects detection performance about as much as if the amount of jamming power is spread over the whole signal bandwidth, where it will often not be much stronger than background noise. By contrast, in narrowband systems where the signal bandwidth is low, the received signal quality will be severely lowered if the jamming power happens to be concentrated on the signal bandwidth.

- Resistance to eavesdropping. The spreading sequence (in DS systems) or the frequency-hopping pattern (in FH systems) is often unknown by anyone for whom the signal is unintended, in which case it obscures the signal and reduces the chance of an adversary making sense of it. Moreover, for a given noise power spectral density (PSD), spread-spectrum systems require the same amount of energy per bit before spreading as narrowband systems and therefore the same amount of power if the bitrate before spreading is the same, but since the signal power is spread over a large bandwidth, the signal PSD is much lower — often significantly lower than the noise PSD — so that the adversary may be unable to determine whether the signal exists at all. However, for mission-critical applications, particularly those employing commercially available radios, spread-spectrum radios do not provide adequate security unless, at a minimum, long nonlinear spreading sequences are used and the messages are encrypted.

- Resistance to fading. The high bandwidth occupied by spread-spectrum signals offer some frequency diversity; i.e., it is unlikely that the signal will encounter severe multipath fading over its whole bandwidth. In direct-sequence systems, the signal can be detected by using a rake receiver.

- Multiple access capability, known as code-division multiple access (CDMA) or code-division multiplexing (CDM). Multiple users can transmit simultaneously in the same frequency band as long as they use different spreading sequences.

Invention of frequency hopping

The idea of trying to protect and avoid interference in radio transmissions dates back to the beginning of radio wave signaling. In 1899 Guglielmo Marconi experimented with frequency-selective reception in an attempt to minimize interference.[2] The concept of Frequency-hopping was adopted by the German radio company Telefunken and also described in part of a 1903 US patent by Nikola Tesla.[3][4] Radio pioneer Jonathan Zenneck's 1908 German book Wireless Telegraphy describes the process and notes that Telefunken was using it previously.[5] It saw limited use by the German military in World War I,[6] was put forward by Polish engineer Leonard Danilewicz in 1929,[7] showed up in a patent in the 1930s by Willem Broertjes (U.S. Patent 1,869,659, issued Aug. 2, 1932), and in the top-secret US Army Signal Corps World War II communications system named SIGSALY.

During World War II, Golden Age of Hollywood actress Hedy Lamarr and avant-garde composer George Antheil developed an intended jamming-resistant radio guidance system for use in Allied torpedoes, patenting the device under US Patent 2,292,387 "Secret Communications System" on August 11, 1942. Their approach was unique in that frequency coordination was done with paper player piano rolls - a novel approach which was never put into practice.[8]

Clock signal generation

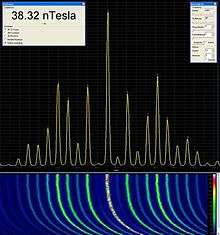

Spread-spectrum clock generation (SSCG) is used in some synchronous digital systems, especially those containing microprocessors, to reduce the spectral density of the electromagnetic interference (EMI) that these systems generate. A synchronous digital system is one that is driven by a clock signal and, because of its periodic nature, has an unavoidably narrow frequency spectrum. In fact, a perfect clock signal would have all its energy concentrated at a single frequency (the desired clock frequency) and its harmonics. Practical synchronous digital systems radiate electromagnetic energy on a number of narrow bands spread on the clock frequency and its harmonics, resulting in a frequency spectrum that, at certain frequencies, can exceed the regulatory limits for electromagnetic interference (e.g. those of the FCC in the United States, JEITA in Japan and the IEC in Europe).

Spread-spectrum clocking avoids this problem by using one of the methods previously described to reduce the peak radiated energy and, therefore, its electromagnetic emissions and so comply with electromagnetic compatibility (EMC) regulations.

It has become a popular technique to gain regulatory approval because it requires only simple equipment modification. It is even more popular in portable electronics devices because of faster clock speeds and increasing integration of high-resolution LCD displays into ever smaller devices. As these devices are designed to be lightweight and inexpensive, traditional passive, electronic measures to reduce EMI, such as capacitors or metal shielding, are not viable. Active EMI reduction techniques such as spread-spectrum clocking are needed in these cases.

However, spread-spectrum clocking, like other kinds of dynamic frequency change, can also create challenges for designers. Principal among these is clock/data misalignment, or clock skew. Consequently, an ability to disable spread-spectrum clocking in computer systems is considered useful.

Note that this method does not reduce total radiated energy, and therefore systems are not necessarily less likely to cause interference. Spreading energy over a larger bandwidth effectively reduces electrical and magnetic readings within narrow bandwidths. Typical measuring receivers used by EMC testing laboratories divide the electromagnetic spectrum into frequency bands approximately 120 kHz wide.[9] If the system under test were to radiate all its energy in a narrow bandwidth, it would register a large peak. Distributing this same energy into a larger bandwidth prevents systems from putting enough energy into any one narrowband to exceed the statutory limits. The usefulness of this method as a means to reduce real-life interference problems is often debated, as it is perceived that spread-spectrum clocking hides rather than resolves higher radiated energy issues by simple exploitation of loopholes in EMC legislation or certification procedures. This situation results in electronic equipment sensitive to narrow bandwidth(s) experiencing much less interference, while those with broadband sensitivity, or even operated at other higher frequencies (such as a radio receiver tuned to a different station), will experience more interference.

FCC certification testing is often completed with the spread-spectrum function enabled in order to reduce the measured emissions to within acceptable legal limits. However, the spread-spectrum functionality may be disabled by the user in some cases. As an example, in the area of personal computers, some BIOS writers include the ability to disable spread-spectrum clock generation as a user setting, thereby defeating the object of the EMI regulations. This might be considered a loophole, but is generally overlooked as long as spread-spectrum is enabled by default.

See also

- Direct-sequence spread spectrum

- Electromagnetic compatibility (EMC)

- Electromagnetic interference (EMI)

- Frequency allocation

- Frequency-hopping spread spectrum

- George Antheil

- HAVE QUICK military frequency-hopping UHF radio voice communication system

- Hedy Lamarr

- Open spectrum

- Orthogonal variable spreading factor (OVSF)

- Spread-spectrum time-domain reflectometry

- Time-hopping spread spectrum

- Ultra-wideband

Notes

- Torrieri, Don (2018). Principles of Spread-Spectrum Communication Systems, 4th ed.

- David Kahn, How I Discovered World War II's Greatest Spy and Other Stories of Intelligence and Code, CRC Press - 2014, pages 157-158

- Tony Rothman, Random Paths to Frequency Hopping, American Scientist, January-February 2019 Volume 107, Number 1, Page 46 americanscientist.org

- Jonathan Adolf Wilhelm Zenneck, Wireless Telegraphy, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Incorporated, 1915, page 331

- David Kahn, How I Discovered World War II's Greatest Spy and Other Stories of Intelligence and Code, CRC Press - 2014, pages 157-158

- Denis Winter, Haig's Command - A Reassessment

- Danilewicz later recalled: "In 1929 we proposed to the General Staff a device of my design for secret radio telegraphy which fortunately did not win acceptance, as it was a truly barbaric idea consisting in constant changes of transmitter frequency. The commission did, however, see fit to grant me 5,000 złotych for executing a model and as encouragement to further work." Cited in Władysław Kozaczuk, Enigma: How the German Machine Cipher Was Broken, and How It Was Read by the Allies in World War II, 1984, p. 27.

- Ari Ben-Menahem, Historical Encyclopedia of Natural and Mathematical Sciences, Volume 1, Springer Science & Business Media - 2009, pages 4527-4530

- American National Standard for Electromagnetic Noise and Field Strength Instrumentation, 10 Hz to 40 GHz—Specifications, ANSI C63.2-1996, Section 8.2 Overall Bandwidth

Sources

- NTIA Manual of Regulations and Procedures for Federal Radio Frequency Management

- National Information Systems Security Glossary

- History on spread spectrum, as given in "Smart Mobs, The Next Social Revolution", Howard Rheingold, ISBN 0-7382-0608-3

- Władysław Kozaczuk, Enigma: How the German Machine Cipher Was Broken, and How It Was Read by the Allies in World War Two, edited and translated by Christopher Kasparek, Frederick, MD, University Publications of America, 1984, ISBN 0-89093-547-5.

- Andrew S. Tanenbaum and David J. Wetherall, Computer Networks, Fifth Edition.