Gnathostomata

Gnathostomata /ˌneɪθoʊstoʊˈmɑːtə/ are the jawed vertebrates. The term derives from Greek: γνάθος (gnathos) "jaw" + στόμα (stoma) "mouth". Gnathostome diversity comprises roughly 60,000 species, which accounts for 99% of all living vertebrates. In addition to opposing jaws, living gnathostomes have teeth, paired appendages,[1] and a horizontal semicircular canal of the inner ear, along with physiological and cellular anatomical characters such as the myelin sheaths of neurons. Another is an adaptive immune system that uses V(D)J recombination to create antigen recognition sites, rather than using genetic recombination in the variable lymphocyte receptor gene.[2]

| Jawed vertebrates | |

|---|---|

| |

| Example of jawed vertebrates: a Siberian tiger (Tetrapoda), an Australian lungfish (Osteichthyes), a Tiger shark (Chondrichthyes) and a Dunkleosteus (Placodermi). | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Olfactores |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Infraphylum: | Gnathostomata |

| Subgroups | |

| |

It is now assumed that Gnathostomata evolved from ancestors that already possessed a pair of both pectoral and pelvic fins.[3] Until recently these ancestors, known as antiarchs, were thought to have lacked pectoral or pelvic fins.[3] In addition to this, some placoderms were shown to have a third pair of paired appendages, that had been modified to claspers in males and basal plates in females—a pattern not seen in any other vertebrate group.[4]

The Osteostraci are generally considered the sister taxon of Gnathostomata.[1][5][6]

It is believed that the jaws evolved from anterior gill support arches that had acquired a new role, being modified to pump water over the gills by opening and closing the mouth more effectively – the buccal pump mechanism. The mouth could then grow bigger and wider, making it possible to capture larger prey. This close and open mechanism would, with time, become stronger and tougher, being transformed into real jaws.

Newer research suggests that a branch of Placoderms was most likely the ancestor of present-day gnathostomes. A 419-million-year-old fossil of a placoderm named Entelognathus had a bony skeleton and anatomical details associated with cartilaginous and bony fish, demonstrating that the absence of a bony skeleton in Chondrichthyes is a derived trait.[7] The fossil findings of primitive bony fishes such as Guiyu oneiros and Psarolepis, which lived contemporaneously with Entelognathus and had pelvic girdles more in common with placoderms than with other bony fish, show that it was a relative rather than a direct ancestor of the extant gnathostomes.[8] It also indicates that spiny sharks and Chondrichthyes represent a single sister group to the bony fishes.[9] Fossils findings of juvenile placoderms, which had true teeth that grew on the surface of the jawbone and had no roots, making them impossible to replace or regrow as they broke or wore down as they grew older, proves the common ancestor of all gnathostomes had teeth and place the origin of teeth along with, or soon after, the evolution of jaws.[10][11]

Late Ordovician-aged microfossils of what have been identified as scales of either acanthodians[12] or "shark-like fishes",[13] may mark Gnathostomata's first appearance in the fossil record. Undeniably unambiguous gnathostome fossils, mostly of primitive acanthodians, begin appearing by the early Silurian, and become abundant by the start of the Devonian.

Classification

The group is traditionally a superclass, broken into three top-level groupings: Chondrichthyes, or the cartilaginous fish; Placodermi, an extinct clade of armored fish; and Teleostomi, which includes the familiar classes of bony fish, birds, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians. Some classification systems have used the term Amphirhina. It is a sister group of the jawless craniates Agnatha.

| Vertebrata |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Subgroups of jawed vertebrates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup | Common name | Example | Comments | |

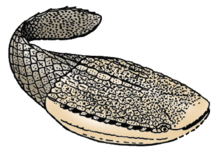

| †Placodermi (extinct) |

Armoured fish | †Placodermi (plate-skinned) is an extinct class of armoured prehistoric fish, known from fossils, which lived from the late Silurian to the end of the Devonian Period. Their head and thorax were covered by articulated armoured plates and the rest of the body was scaled or naked, depending on the species. Placoderms were among the first jawed fish; their jaws likely evolved from the first of their gill arches. A 380-million-year-old fossil of one species represents the oldest known example of live birth.[14] The first identifiable placoderms evolved in the late Silurian; they began a dramatic decline during the Late Devonian extinctions, and the class was entirely extinct by the end of the Devonian. | ||

| Chondrichthyes | Cartilaginous fishes | Chondrichthyes (cartilage-fish) or cartilaginous fishes are jawed fish with paired fins, paired nares, scales, a heart with its chambers in series, and skeletons made of cartilage rather than bone. The class is divided into two subclasses: Elasmobranchii (sharks, rays and skates) and Holocephali (chimaeras, sometimes called ghost sharks, which are sometimes separated into their own class). Within the infraphylum Gnathostomata, cartilaginous fishes are distinct from all other jawed vertebrates, the extant members of which all fall into Teleostomi. | ||

| †?Acanthodii (extinct) |

Spiny sharks |  |

†Acanthodii, or spiny sharks are a class of extinct fishes, sharing features with both bony and cartilaginous fishes, now understood to be a paraphyletic assemblage leading to modern Chondrichthyes.[9] In form they resembled sharks, but their epidermis was covered with tiny rhomboid platelets like the scales of holosteans (gars, bowfins). They may have been an independent phylogenetic branch of fishes, which had evolved from little-specialized forms close to Recent Chondrichthyes. Acanthodians did, in fact, have a cartilaginous skeleton, but their fins had a wide, bony base and were reinforced on their anterior margin with a dentine spine. They are distinguished in two respects: they were the earliest known jawed vertebrates, and they had stout spines supporting their fins, fixed in place and non-movable (like a shark's dorsal fin). The acanthodians' jaws are presumed to have evolved from the first gill arch of some ancestral jawless fishes that had a gill skeleton made of pieces of jointed cartilage. The common name "spiny sharks" is really a misnomer for these early jawed fishes. The name was coined because they were superficially shark-shaped, with a streamlined body, paired fins, and a strongly upturned tail; stout bony spines supported all the fins except the tail - hence, "spiny sharks". | |

| Osteichthyes | Bony fishes |  |

Osteichthyes or bony fishes are a taxonomic group of fish that have bone, as opposed to cartilaginous skeletons. The vast majority of fish are osteichthyes, which is an extremely diverse and abundant group consisting of 45 orders, with over 435 families and 28,000 species.[15] It is the largest class of vertebrates in existence today. Osteichthyes is divided into the ray-finned fish (Actinopterygii) and lobe-finned fish (Sarcopterygii). The oldest known fossils of bony fish are about 420 million years ago, which are also transitional fossils, showing a tooth pattern that is in between the tooth rows of sharks and bony fishes.[16] | |

| Tetrapoda | Tetrapods | .jpg) |

Tetrapoda (four-feet) or tetrapods are the group of all four-limbed vertebrates, including living and extinct amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. Amphibians today generally remain semi-aquatic, living the first stage of their lives as fish-like tadpoles. Several groups of tetrapods, such as the reptillian snakes and mammalian cetaceans, have lost some or all of their limbs, and many tetrapods have returned to partially aquatic or (in the case of cetaceans and sirenians) fully aquatic lives. The tetrapods evolved from the lobe-finned fishes about 395 million years ago in the Devonian.[17] The specific aquatic ancestors of the tetrapods, and the process by which land colonization occurred, remain unclear, and are areas of active research and debate among palaeontologists at present. | |

References

- Zaccone, Giacomo; Dabrowski, Konrad; Hedrick, Michael S. (5 August 2015). Phylogeny, Anatomy and Physiology of Ancient Fishes. CRC Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-4987-0756-5. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- Cooper MD, Alder MN (February 2006). "The evolution of adaptive immune systems". Cell. 124 (4): 815–22. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.001. PMID 16497590.

- New study showing pelvic girdles arose before the origin of movable jaws

- "The first vertebrate sexual organs evolved as an extra pair of legs". Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2014-07-04.

- Keating, Joseph N.; Sansom, Robert S.; Purnell, Mark A. (2012). "A new osteostracan fauna from the Devonian of the Welsh Borderlands and observations on the taxonomy and growth of Osteostraci" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (5): 1002–1017. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.693555. ISSN 0272-4634.

- Sansom, R. S.; Randle, E.; Donoghue, P. C. J. (2014). "Discriminating signal from noise in the fossil record of early vertebrates reveals cryptic evolutionary history". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282 (1800): 2014–2245. doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.2245. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 4298210. PMID 25520359.

- Scientists make jaw dropping discovery

- Zhu, Min; Yu, Xiaobo; Choo, Brian; Qu, Qingming; Jia, Liantao; Zhao, Wenjin; Qiao, Tuo; Lu, Jing (2012). "Fossil Fishes from China Provide First Evidence of Dermal Pelvic Girdles in Osteichthyans". PLOS ONE. 7 (4): e35103. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...735103Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0035103. PMC 3318012. PMID 22509388.

- Min Zhu; et al. (10 October 2013). "A Silurian placoderm with osteichthyan-like marginal jaw bones". Nature. 502 (7470): 188–193. Bibcode:2013Natur.502..188Z. doi:10.1038/nature12617. PMID 24067611.

- Choi, Charles Q. (17 October 2012). "Evolution's Bite: Ancient Armored Fish Was Toothy, Too". Live Science.

- ScienceShot: Ancient Jaws Had Real Teeth

- Hanke, Gavin F.; Wilson, Mark V. H. (2004). "New teleostome fishes and acanthodian systematics." (PDF). Recent advances in the origin and early radiation of vertebrates. pp. 189–216.

... record of acanthodian fishes is limited to microremains from the latest Ordovician (JANVIER 1996)

- Sansom, Ivan J.; Smith, Moya M.; Smith, M. Paul (February 15, 1996). "Scales of thelodont and shark-like fishes from the Ordovician of Colorado". Nature. 379 (6566): 628–630. Bibcode:1996Natur.379..628S. doi:10.1038/379628a0.

- "Fossil reveals oldest live birth". BBC. May 28, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- Bony fishes Archived 2013-06-06 at the Wayback Machine SeaWorld. Retrieved 2 February 2013.

- Jaws, Teeth of Earliest Bony Fish Discovered

- Clack 2012