Eteocypriot language

Eteocypriot was a pre-Indo-European language spoken in Iron Age Cyprus. The name means "true" or "original Cypriot" parallel to Eteocretan, both of which names are used by modern scholarship to mean the pre-Greek languages of those places.[3] Eteocypriot was written in the Cypriot syllabary, a syllabic script derived from Linear A (via the Cypro-Minoan variant Linear C). The language was under pressure from Arcadocypriot Greek from about the 10th century BC and finally became extinct in about the 4th century BC.

| Eteocypriot | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Formerly spoken in Cyprus |

| Region | Eastern Mediterranean Sea |

| Era | 10th to 4th century BC[1] |

| Cypriot syllabary | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | ecy |

ecy | |

| Glottolog | eteo1240[2] |

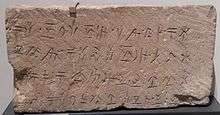

One of the Eteocypriot inscriptions from Amathus | |

The language is as yet unknown except for a small vocabulary attested in bilingual inscriptions. Such topics as syntax and possible inflection or agglutination remain a mystery. Partial translations depend to a large extent on the language or language group assumed by the translator, but there is no consistency. It is conjectured by some linguists to be related to the Etruscan and Lemnian languages, and by others to be Northwest Semitic. Those who do not advocate any of those theories often adopt the default of an unknown pre-Greek language. Due to the small number of texts found, there is currently much unproven speculation.

Eteocypriot may be descended from the language of the Cypro-Minoan inscriptions, a collection of poorly-understood inscriptions from Bronze Age Cyprus. Both Cypro-Minoan and Eteocypriot share a common genitive suffix -o-ti.[4]

Corpus

Several hundred inscriptions written in the Cypriot syllabary (VI-III BC) cannot be interpreted in Greek. While it does not necessarily imply that all of them are non-Greek, there are at least two locations where multiple inscriptions with clearly non-Greek content were found:

- Amathus (including a bilingual Eteocypriot-Greek text)

- a few short inscriptions from Golgoi (currently Athienou: Markus Egetmeyer suggested that their language (which he calls Golgian resp. Golgisch in German) may be different from those of Amathus[5]).

While the language of Cypro-Minoan inscriptions is often supposed to be the same as (or ancestral to) Eteocypriot, that has yet to be proven, as the script is only partly legible.

Amathus bilingual

The most famous Eteocypriot inscription is a bilingual text inscribed on a black marble slab found on the acropolis of Amathus about 1913, dated to around 600 BC and written in both the Attic dialect of Ancient Greek and Eteocypriot. The Eteocypriot text in Cypriot characters runs right to left; the Greek text in all capital Greek letters, left to right. The following are the syllabic values of the symbols of the Eteocypriot text (left to right) and the Greek text as is:

- Eteocypriot:

- 1: a-na ma-to-ri u-mi-e-s[a]-i mu-ku-la-i la-sa-na a-ri-si-to-no-se a-ra-to-wa-na-ka-so-ko-o-se

- 2: ke-ra-ke-re-tu-lo-se ta-ka-na-[?-?]-so-ti a-lo ka-i-li-po-ti[6]

- A suggested pronunciation is:

- 1: Ana mator-i um-iesa-i Mukula-i Lasana Ariston-ose Artowanaksoko-ose

- 2: kera keretul-ose. Ta kana (kuno) sot-i, ail-o kail-i pot-i.

- Greek:

- 3: Η ПΟΛΙΣ Η АΜАΘΟΥΣΙΩΝ ΑΡΙΣΤΩΝΑ

- 4: ΑΡΙΣΤΩΝΑΚΤΟΣ ΕΥΠΑΤΡΙΔΗΝ

- which might be rendered into modern script as:

- 3: Ἡ πόλις ἡ Ἀμαθουσίων Ἀριστῶνα

- 4: 'Ἀριστώνακτος, εὐπατρίδην.

Cyrus H. Gordon translates this text as

- The city of the Amathusans (honored) the noble Ariston (son) of Aristonax.[7]

Gordon's translation is based on Greek inscriptions in general and the fact that "the noble Ariston" is in the accusative case, implying a transitive verb. Gordon explains that "the verb is omitted ... in such dedicatory inscriptions".

The inscription is important as verifying that the symbols of the unknown language, in fact, have about the same phonetic values as they do when they are used to represent Greek. Gordon says, "This bilingual proves that the signs in Eteocypriot texts have the same values as in the Cypriot Greek texts...."[7] However, as a bilingual it uses only a few Greek syllables to translate many Eteocypriot ones, which adds to its mystery.

See also

- Aegean language family

- Cypriot syllabary

- Cypro-Minoan language

- Eteocretan

References

- Eteocypriot at MultiTree on the Linguist List

- Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds. (2017). "Eteocypriot". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- The derivation is given in Partridge, Eric (1983) Origins: A short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English, New York: Greenwich House, ISBN 0-517-41425-2. The term Eteocypriot was devised by Friedrich in 1932, according to Olivier Masson in ETEO-CYPRIOT, an article in Zbornik, Issues 4–5, 2002–2003. Eteocretan is based on a genuine Ancient Greek word.

- Valério 2016

- M. Egetmeyer, ‘„Sprechen Sie Golgisch?“ Anmerkungen zu einer übersehenen Sprache’ Études mycéniennes 2010: 427-434

- The inscription is given as portrayed in Gordon, Evidence, Page 5. Breaks in the stone obscure the syllables in brackets.

- Forgotten Scripts, p. 120.

Sources

- Duhoux, Yves. Eteocypriot and Cypro-Minoan.

- Gordon, Cyrus (1966). Evidence for the Minoan Language. Ventnor, New Jersey: Ventnor Publishers.

- Gordon, Cyrus (1982). Forgotten Scripts: Their Ongoing Discovery and Decipherment: Revised and Enlarged Edition. New York: Basic Books, Inc. ISBN 0-465-02484-X.

- Jones, Tom B., Notes on the Eteocypriot inscriptions, American journal of philology. LXXI 1950, c. 401–407

- Steele, Philippa M. (2013). A linguistic history of Ancient Cyprus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-04286-5.