Nakayama Tadayasu

Marquess Nakayama Tadayasu (Japanese 中山 忠能, 17 December 1809 – 12 June 1888) was a Japanese nobleman and courtier of the Edo period and then one of the Kazoku of the post-1867 Empire of Japan. He was the father of Nakayama Yoshiko (1834–1907), mother of the Emperor Meiji, who was born and brought up in Nakayama's household.[1] He had the rare honour of being awarded the Order of the Chrysanthemum while still alive.[2]

Early life

The second son of Nakayama Tadayori, a member of the Kuge, or court nobility,[3] in 1821, at the age of eleven, Nakayama was named as Provisional Major-General of the Imperial Guard of the Left.[4]

Nakayama married Matsura Aiko (1818–1906), a daughter of Matsura Kiyoshi (1760–1841), ninth daimyō (feudal ruler) of Hirado and a famous swordsman.[2]

Courtier

Nakayama received a series of court appointments in the service of the Emperor Ninkō (1800–1846) and his successor Kōmei (1831–1867). In 1844 he became a Provisional Middle Councillor, in 1847 a Provisional Grand Councillor, and the next year a Senior Second-rank Councillor. From 1849 he was several times the Emperor Kōmei's personal envoy and secretary. In 1851 one of Nakayama's daughters, Yoshiko, joined the court as a Provisional Lady-in-Waiting, and the next year she gave birth to the Emperor's son.[4] Nakayama was entrusted with the upbringing of his grandson, Mutsuhito, the future Emperor Meiji, and many years later with that of his great-grandson Yoshihito, another future emperor.[5] In the case of Mutsuhito, Nakayama was also officially his guardian.[6] Yoshihito was moved to Nakayama's house on 7 December 1879, when barely three months old. He was a sickly infant, and Nakayama spent many days and nights with him.[7]

In 1858, Nakayama was a leader of courtiers protesting against the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Japan and the United States, which opened the ports of Kanagawa, Kobe, Nagasaki, Niigata, and Hakodate to foreign trade and also to settlement by Americans.[4] In December 1862, Nakayama was appointed as the Emperor's Special Consultant for National Affairs, but in 1864 he was sent away from court as a consequence of his involvement in the Kinmon Incident, an attempt to control the Emperor. However, this banishment was ended in January 1867 when Kōmei died unexpectedly and Nakayama's grandson, a boy aged only fourteen, came to the imperial throne.[4]

On 3 January 1868, when Iwakura Tomomi arranged the seizure of the Kyoto Imperial Palace and initiated the Meiji Restoration, which resulted in the creation of the post-Shōgun Empire of Japan, Nakayama was among the courtiers who supported this action. According to Peter Kornicki, "Nakayama's cooperation with Iwakura had been essential to the success of the coup d'etat".[8] Nakayama and Iwakura both became influential courtier-politicians in the Meiji period.[9]

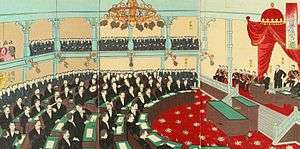

Appointed a member of the Order of the Rising Sun, first class, in 1880, Nakayama was created a Marquess in 1884,[6] when the Emperor created a new hierarchical peerage on European lines. This gave him a seat in the House of Peers, the upper house of the Imperial Diet. On 14 May 1888, a month before his death, he received the supreme accolade of being awarded the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum during his lifetime,[2] a rarely bestowed honour.

Honours

Court ranks

- Fifth rank, junior grade (1810)

- Fifth rank, senior grade (1812)

- Senior fifth rank, junior grade (1814)

- Fourth rank, junior grade (1816)

- Fourth rank, senior grade (1818)

- Senior fourth rank, junior grade (1820)

- Senior fourth rank, senior grade (1834)

- Third rank (1841)

- Senior third rank (1843)

- Second rank (1845)

- Senior second rank (1848)

- First rank (1868)

Titles

- Marquess (7 July 1884)

Decorations

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun (2 November 1880)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Chrysanthemum (14 May 1888)[10]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Nakayama Tadayasu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes

- Ben-Ami Shillony, The Emperors of Modern Japan (2008), p. 213

- The "Japan Gazette" Peerage of Japan (Japan Gazette, 1st edition, 1912), p. 57

- Norman Havens, Nobutaka Inoue, An Encyclopedia of Shinto (Shinto Jiten) (2006), p. 185

- Takeda Hideaki, Nakayama Tadayasu (1809–88) at kokugakuin.ac, accessed 24 September 2013

- Donald Calman, Nature and Origins of Japanese Imperialism (2013), pp. 92–93

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Vol. 32 (1922), p. 1,094

- Donald Keene, Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852–1912 (2001; reprinted 2013), p. 321

- Peter Francis Kornicki, The emergence of the Meiji state (1998), p. 115

- Masako Gavin, Ben Middleton, Japan and the High Treason Incident (2013), p. 50

- Genealogy

- "中山家(羽林家) (Nakayama genealogy)". Reichsarchiv. Retrieved 26 October 2017. (in Japanese)