Toyohara Chikanobu

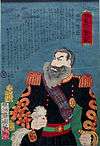

Toyohara Chikanobu (豊原周延, 1838–1912), better known to his contemporaries as Yōshū Chikanobu (楊洲周延), was a prolific woodblock artist of Japan's Meiji (era).

Names

Chikanobu signed his artwork "Yōshū Chikanobu" (楊洲周延). This was his "art name" (作品名, sakuhinmei). The artist's "real name" (本名, honmyō) was Hashimoto Naoyoshi (橋本直義); and it was published in his obituary.[1]

Many of his earliest works were signed "studio of Yōshū Chikanobu" (楊洲齋周延, Yōshū-sai Chikanobu); a small number of his early creations were simply signed "Yōshū" (楊洲). At least one triptych from 12 Meiji (1879) exists signed "Yōshū Naoyoshi" (楊洲直義).

The portrait of the Emperor Meiji held by the British Museum is inscribed "drawn by Yōshū Chikanobu by special request" (應需楊洲周延筆, motome ni ōjite Yōshū Chikanobu hitsu).[2]

No works have surfaced that are signed either "Toyohara Chikanobu" or "Hashimoto Chikanobu".[3]

Military career

Chikanobu was a retainer of the Sakakibara clan of Takada Domain in Echigo Province. After the collapse of the Tokugawa Shogunate, he joined the Shōgitai and fought in the Battle of Ueno.[1]

He joined Tokugawa loyalists in Hakodate, Hokkaidō, where he fought in the Battle of Hakodate at the Goryōkaku star fort. He served under the leadership of Enomoto Takeaki and Ōtori Keisuke; and he achieved fame for his bravery.[1]

Following the Shōgitai's surrender, he was remanded along with others to the authorities in the Takada domain.[1]

Artistic career

In 1875 (Meiji 8), he decided to try to make a living as an artist. He travelled to Tokyo. He found work as an artist for the Kaishin Shimbun.[4] In addition, he produced nishiki-e artworks.[1] In his younger days, he had studied the Kanō school of painting; but his interest was drawn to ukiyo-e. He studied with a disciple of Keisai Eisen and then he joined the school of Ichiyūsai Kuniyoshi; during this period, he called himself Yoshitsuru. After Kuniyoshi’s death, he studied with Kunisada. He also referred to himself as Yōshū.[1]

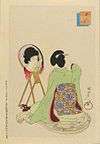

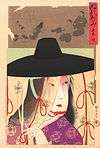

Like many ukiyo-e artists, Chikanobu turned his attention towards a great variety of subjects. His work ranged from Japanese mythology to depictions of the battlefields of his lifetime to women's fashions. As well as a number of the other artists of this period, he too portrayed kabuki actors in character, and is well known for his impressions of the mie (mise en scène) of kabuki productions. Chikanobu was known as a master of bijinga.[1] images of beautiful women, and for illustrating changes in women's fashion, including both traditional and Western clothing. His work illustrated the changes in coiffures and make-up across time. For example, in Chikanobu's images in Mirror of Ages (1897), the hair styles of the Tenmei era, 1781-1789[5] are distinguished from those of the Keiō era, 1865-1867.[6] His works capture the transition from the age of the samurai to Meiji modernity, the artistic chaos of the Meiji period exemplifying the concept of "furumekashii/imamekashii".[7]

.jpg)

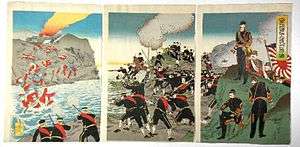

Chikanobu is a recognizable Meiji period artist,[8] but his subjects were sometimes drawn from earlier historical eras. For example, one print illustrates an incident during the 1855 Ansei Edo earthquake.[9] The early Meiji period was marked by clashes between disputing samurai forces with differing views about ending Japan's self-imposed isolation and about the changing relationship between the Imperial court and the Tokugawa shogunate.[10] He created a range of impressions and scenes of the Satsuma Rebellion and Saigō Takamori.[11] Some of these prints illustrated the period of domestic unrest and other subjects of topical interest, including prints like the 1882 image of the Imo Incident, also known as the Jingo Incident (壬午事変, jingo jihen) at right.

The greatest number of Chikanobu's war prints (戦争絵, sensō-e) appeared in triptych format. These works documented the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895. For example, the "Victory at Asan"[12] was published with a contemporaneous account of the July 29, 1894 battle.

Among those influenced by Chikanobu were Nobukazu (楊斎延一, Yōsai Nobukazu) and Gyokuei (楊堂玉英, Yōdō Gyokuei).[1]

Genres

Battle scenes

Examples of battle scenes (戦争絵, sensō-e) include:

- Boshin War 1868–1869 (戊辰戦争, Boshin sensō)

- Satsuma Rebellion 1877 (西南戦争, Seinan sensō)

Examples of scenes from this war include:

A scene from the battle at Kagoshima

A scene from the battle at Kagoshima An Assemblage of the Heroines of Kagoshima

An Assemblage of the Heroines of Kagoshima The battle at Nobeoka

The battle at Nobeoka

- Jingo Incident Korea 1882 (壬午事変, Jingo Jihen)

Examples of scenes from this war include:

A sea-land battle from the Korean Uprising

A sea-land battle from the Korean Uprising The Japanese Mission to the Koreans

The Japanese Mission to the Koreans A battle scene from the Korean Incident

A battle scene from the Korean Incident

- Sino-Japanese War 1894–1895 (日清戦争, Nisshin sensō)

Examples of scenes from this war include:

A battle scene from the First Sino-Japanese War

A battle scene from the First Sino-Japanese War A battle scene from the First Sino-Japanese War

A battle scene from the First Sino-Japanese War A battle scene from the First Sino-Japanese War

A battle scene from the First Sino-Japanese War

- Russo-Japanese War 1904–5 (日露戦争, Nichiro sensō)

Examples of scenes from this war include:

A battle scene from the Russo-Japanese War

A battle scene from the Russo-Japanese War

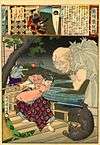

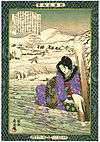

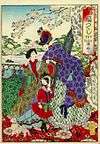

Warrior prints

Examples of warrior prints (武者絵, Musha-e) include:

Gempei Seisuiki series,Miura Daisuke Yoshiaki (1093-1181)

Gempei Seisuiki series,Miura Daisuke Yoshiaki (1093-1181) Azuma nishiki chūya kurabe series, Kusunoki Masatsura attacking an oni

Azuma nishiki chūya kurabe series, Kusunoki Masatsura attacking an oni Setsu Gekka (1st series),Takiyasha-hime, daughter of Taira no Masakado

Setsu Gekka (1st series),Takiyasha-hime, daughter of Taira no Masakado

Sakakibara Yasumasa and Toyotomi Hideyoshi on Mt. Komaki

Sakakibara Yasumasa and Toyotomi Hideyoshi on Mt. Komaki Tomoe Gozen with Uchida Ieyoshi and Hatakeyama no Shigetada

Tomoe Gozen with Uchida Ieyoshi and Hatakeyama no Shigetada

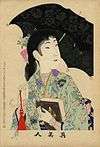

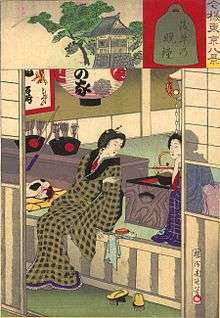

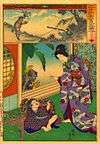

Beauty pictures

Examples of "beauty pictures" (美人画, Bijin-ga) include:

Azuma series, keshō

Azuma series, keshō Shin Bijin series, No. 12

Shin Bijin series, No. 12 Setsu Gekka (second series), suimen no tsuki

Setsu Gekka (second series), suimen no tsuki Gentō Shashin Kurabe series, Arashiyama

Gentō Shashin Kurabe series, Arashiyama Jidai Kagami series, Kenmu nengō (era)

Jidai Kagami series, Kenmu nengō (era) azuma fūzoku nenjū gyōji series, 6th month

azuma fūzoku nenjū gyōji series, 6th month Kyōdō risshiki album No. 42 Chikako

Kyōdō risshiki album No. 42 Chikako

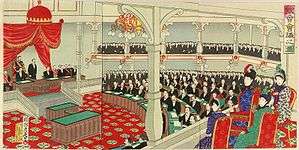

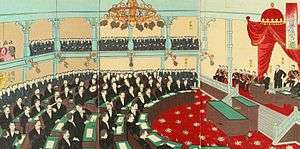

Historical pictures

Examples of historical scenes (史教画, Reshiki-ga) include: Recent (Meiji era) history

A scene of the Japanese Diet

A scene of the Japanese Diet A Scene in the House of Peers

A Scene in the House of Peers A scene of a meeting of the Privy Council

A scene of a meeting of the Privy Council

Ancient history

Nihon Rekishi Kyokun series – Lessons from Japan's History - Shiragi Saburō and Tokiaki

Nihon Rekishi Kyokun series – Lessons from Japan's History - Shiragi Saburō and Tokiaki Nihon Rekishi Kyokun series – Lessons from Japan's History - Tajima no kami Norimasa

Nihon Rekishi Kyokun series – Lessons from Japan's History - Tajima no kami Norimasa

Famous places

Examples of scenic spots (名所絵, Meisho-e) include:

Meisho Bijin Awase series, Matsushima in Rikuzen Province |

gentō shashin kurabe series, Oji no taki |

Nikko Mesho series, Hannya and Hoto Waterfalls |

Kameido Tenjin Shrine |

Enlightenment pictures

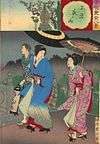

Examples of "enlightenment pictures" (文明開化絵, Bunmei kaika-e) include:

Women and girls in Western dress with various hairstyles

|

shin bijin series:Woman with Western-style umbella and book

|

azuma fūzoku fuku tsukushi series:Western-style clothing |

mitate jūnishi series:Depiction of mixed clothing styles |

Theatre scenes

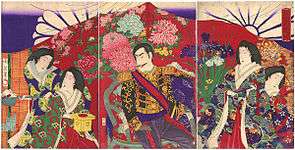

Examples of "kabuki scenes/actor portraits" (役者絵, Yakusha-e) include:

Kabuki scene

Kabuki scene Kabuki scene

Kabuki scene Kuronushi attempting to cut down a cherry tree[13]

Kuronushi attempting to cut down a cherry tree[13] Kabuki scene

Kabuki scene Kabuki scene depicting a samurai of the Sanada carrying a cannon

Kabuki scene depicting a samurai of the Sanada carrying a cannon Kabuki scene

Kabuki scene

Memorial prints

Examples of "Memorial prints" (死絵, Shini-e) include:

Iwai Hanshiro VIII, 1829-1882

Iwai Hanshiro VIII, 1829-1882 Iwai Hanshiro VIII

Iwai Hanshiro VIII

Women's pastimes

Examples of "Etiquette and Manners for Women" (女禮式, joreishiki) include:

Azuma kai series:Watching cherry blossoms fall (hanami)

Azuma kai series:Watching cherry blossoms fall (hanami) Kaika kyōiku mari uta series:teaching songs with koto and gekkin

Kaika kyōiku mari uta series:teaching songs with koto and gekkin Shin bijin series:Practicing kanji

Shin bijin series:Practicing kanji Nijūshi kō mitate e awase series:Weaving Tōei

Nijūshi kō mitate e awase series:Weaving Tōei Setsu gekka series II:creating bonseki

Setsu gekka series II:creating bonseki Azuma fūzoku fuku tsukushiseries:purchasing kimono cloth at the drapers

Azuma fūzoku fuku tsukushiseries:purchasing kimono cloth at the drapers Fugaku shū series:Women digging clams at the beach

Fugaku shū series:Women digging clams at the beach

Typical Meiji era pastimes

Typical Meiji era pastimes

Japanese Flower Arranging Ikebana

Japanese Flower Arranging Ikebana

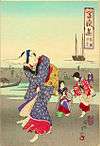

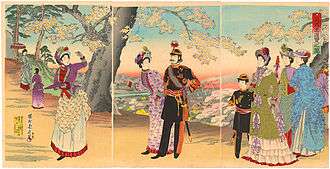

Emperor Meiji pictures

Examples of Emperor Meiji relaxing include:

Emperor Meiji at a Flower Show

Emperor Meiji at a Flower Show Emperor Meiji at Asukayama Park

Emperor Meiji at Asukayama Park Emperor Meiji enjoying the cool evening

Emperor Meiji enjoying the cool evening

Contrast pictures

Examples of "Contrast prints" (見立絵, Mitate-e) include:

Mitate jūni shi series The Sign of the Ox

Mitate jūni shi series The Sign of the Ox Gentō shashin kurabe series Kanjinchō

Gentō shashin kurabe series Kanjinchō Imayō tōkyō hakkei series Evening bell at Asakusa

Imayō tōkyō hakkei series Evening bell at Asakusa Nijūshi Kō Mitate E Awase series The Deer Milker

Nijūshi Kō Mitate E Awase series The Deer Milker

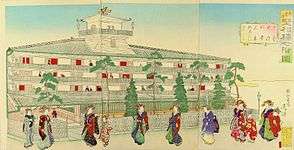

Glorification of the Geisha

Examples of this genre include:

meiyo iro no sakiwake series:reading a letter

|

Katamura-rō in the Yoshiwara

|

imayō tōkyō hakkei series:walking with an escort

|

Formats

Like the majority of his contemporaries, he worked mostly in the ōban tate-e[14] format. There are quite a number of single panel series, as well as many other prints in this format which are not a part of any series.

He produced several series in the ōban yoko-e[15] format, which were usually then folded cross-wise to produce an album.

Although he is, perhaps, best known for his triptychs, single topics and series, two diptych series are known as well. There are, at least, two polyptych[16] prints known.[17]

His signature may also be found in the line drawings and illustrations in a number of ehon (絵本), which were mostly of a historical nature. In addition, there are fan prints uchiwa-e (団扇絵), as well as number of sheets of sugoroku (すごろく) with his signature that still exist and at least three prints in the kakemono-e[18] format were produced in his latter years.

Selected works

In a statistical overview derived from writings by and about Hashimoto Toyohara, OCLC/WorldCat encompasses roughly 300+ works in 300+ publications in 2 languages and 700+ library holdings[19]

- 鳥追阿松海上新話. 初編 (1878)

- 鳥追阿松海上新話. 2編 (1878)

- 五人殲苦魔物語. 初編 (1879)

- 艷娘毒蛇淵. 2編上の卷 (1880)

- 白菖阿繁顛末. 3編 (1880)

- 沢村田之助曙草紙. 初編 (1880)

- 浪枕江の島新語. 3編下之卷 (1880)

- 浪枕江の島新語. 3編中之卷 (1880)

- 浪枕江の島新語. 3編上之卷 (1880)

- 浪枕江の島新語. 初編上之卷 (1880)

- 浪枕江の島新語. 2編下之卷 (1880)

- 坂東彥三倭一流. 初編 (1880)

- 川上行義復讐新話. 2編下の卷 (1881)

- 川上行義復讐新話. 初編上之卷 (1881)

- 真田三代記 : 絵本. 初編 (1882)

- 明良双葉艸. 8編上 (1888)

- 明良双葉艸. 5編上 (1888)

- 千代田之大奥 by 楊洲周延 (1895)

Notes

- See "Yōshū Chikanobu [obituary]," Miyako Shimbun, No. 8847 (October 2, 1912). p. 195:

"Yōshū Chikanobu, who represented in nishiki-e the Great Interior of the Chiyoda Castle and was famous as a master of bijin-ga, had retired to Shimo-Ōsaki at the foot of Goten-yama five years ago and led an elegant life away from the world, but suffered from stomach cancer starting this past June, and finally died on the night of September 28th at the age of seventy-five.

His real name being Hashimoto Naoyoshi, he was a retainer of the Sakakibara clan of Takada domain in Echigo province. After the collapse of the Tokugawa Shogunate, he joined the Shōgitai and fought in the Battle of Ueno. After the defeat at Ueno, he fled to Hakodate, Hokkaidō, fought in the Battle of Hakodate at the Goryōkaku star fort under the leadership of Enomoto Takeaki and Ōtori Keisuke achieving fame for his bravery. But following the Shōgitai’s surrender, he was handed over to the authorities in the Takada domain. In the eighth year of Meiji, with the intention of making a living in the way that he was fond of, went to the capital and lived in Yushima-Tenjin town. He became an artist for the Kaishin Shimbun, and on the side, produced many nishiki-e pieces. Regarding his artistic background: when he was younger he studied the Kanō school of painting, but later switched to ukiyo-e and studied with a disciple of Keisai Eisen; and next joining the school of Utagawa Kuniyoshi , called himself Yoshitsuru. After Kuniyoshi’s death, he studied with Kunisada. Later he studied nigao-e with Toyohara Kunichika, and called himself Isshunsai Chikanobu. He also referred to himself as Yōshū.

Among his disciples were Nobukazu (楊斎延一, Yōsai Nobukazu) and Gyokuei (楊堂玉英, Yōdō Gyokuei) as a painter of images on fans (uchiwa-e), and several others. Gyokuei produced Kajita Hanko. Since only Nobukazu now is in good health, there is no one to succeed to Chikanobu’s bijin-ga, and thus Edo-e, after the death of Kunichika, has perished with Chikanobu. It is most regrettable." — trans. by Kyoko Iriye Selden (October 2, 1936, Tokyo-January 20, 2013, Ithaca), Senior Lecturer, Department of Asian Studies, Cornell University, ret'd. - British Museum, woodblock print. Portrait of the Meiji Emperor

- Library of Congress

- 改進新聞 (かいしんしんぶん)

- "Tenmei, 1781-1789 :: Chikanobu and Yoshitoshi Woodblock Prints". Ccdl.libraries.claremont.edu. Retrieved 2012-10-08.

- "Keio, 1865-1867 :: Chikanobu and Yoshitoshi Woodblock Prints". Ccdl.libraries.claremont.edu. Retrieved 2012-10-08.

- Miner, Odagiri and Morrell in the Princeton Companion to Classical Japanese Literature, pp. 9, 27.

- Gobrich, Marius. "Edo to Meiji: Ukiyo-e artist Yoshu Chikanobu tracked the transformation of Japanese culture," Japan Times. March 6, 2009; excerpt, "We think the characteristics of the artist start to show around the late 1880s.... Before this, in his early works, he tends to imitate his teacher, Toyohara Kunichika."

- Gobrich, "Edo to Meiji," Japan Times. March 6, 2009; excerpt, " One picture shows people escaping from a collapsing house during the Ansei Edo earthquake of 1855, which reportedly killed over 6,000 people and destroyed much of the city. What gives this image a particularly timeless feel is the fact that the noble lady of the house — in accordance with the rules of etiquette and social decorum — has taken the trouble to get into her palanquin first before being carried out of the collapsing house.."

- "Yōshū Chikanobu [obituary]," Miyako Shimbun, No. 8847 (October 2, 1912). p. 195; Gobrich, "Edo to Meiji," Japan Times. March 6, 2009; excerpt, "[Chikanobu] was originally a samurai vassal of the Tokugawa Shogunate who saw action in the Boshin War (1868-69), which ended the country's feudal system."

- British Museum, Meiji shoshi nenkai kiji, 1877; woodblock print, triptych. Saigo Takamori and his followers in the Satsuma rebellion

- "Victory at Asan, Korea; Sino-Japanese war :: Chikanobu and Yoshitoshi Woodblock Prints". Ccdl.libraries.claremont.edu. 2001-02-26. Retrieved 2012-10-08.

- Cavaye, Ronald et al. (2004). A Guide to the Japanese Stage: from Traditional to Cutting Edge, pp. 138-139., p. 138, at Google Books

- The ōban tate-e (大判竪絵) format is ~35 x 24.5 cm or about 14" x 9.75" and is vertically oriented. For further information about woodblock formats, please see Woodblock printing in Japan

- The ōban yoko-e (大判竪絵) format is ~24.5 x ~35 cm or about 9.75" x 14" and is horizontally positioned. For further information about woodblock formats, please see Woodblock printing in Japan

- referring in this case to more than three panels

- one of which is a five panel print from the series, "The Imperial Ladies' Quarters at Chiyoda Palace" entitled, konrei (こんれい) The Marriage Ceremony. The other is a very well known nine-panel print entitled Meiji Sanjū-Ichi-Nen Shi-Gatsu Tōka: Tento Sanjū-Nen Shukugakai Yokyō Gyōretsu no Zu (明治31年4月10日: 奠都30年祝賀會餘興行列の図), The Procession in Commemoration of the Thirtieth Anniversary of the Transfer of the Capital.

- The kakemono-e (掛物絵) format is ~71.8 x ~24.4 cm or about 28.3" x 9.6" and consists of two vertically positioned oban tate-e prints joined on the shorter side. For further information about woodblock formats, please see Woodblock printing in Japan

- "鳥追阿松海上新話. 初編". Worldcat.org. Retrieved 2012-10-08.

Further reading

- Cavaye, Ronald; Paul Griffith; Akihiko Senda and Mansai Nomura. (2004). A Guide to the Japanese Stage: from Traditional to Cutting Edge. Tokyo: Kōdansha. ISBN 978-4-7700-2987-4; OCLC 148109695

- Coats, Bruce; Kyoko Kurita; Joshua S. Mostow and Allen Hockley. (2006). Chikanobu: Modernity And Nostalgia in Japanese Prints. Leiden: Hotei. ISBN 978-90-04-15490-2; ISBN 978-90-74822-88-6; OCLC 255142506

- Till, Barry. (2010). "Woodblock Prints of Meiji Japan (1868-1912): A View of History Though Art". Hong Kong: Arts of Asia. Vol. XL, no.4, pp. 76–98. ISSN 0004-4083; OCLC 1514382

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Toyohara Chikanobu. |