Empress Shōken

Empress Shōken (昭憲皇后, Shōken-kōgō, 9 May 1849 – 9 April 1914), also known as Empress Dowager Shōken (昭憲皇太后, Shōken-kōtaigō), was the wife of Emperor Meiji of Japan.

| Shōken | |

|---|---|

| |

| Empress consort of Japan | |

| Tenure | 11 January 1869 – 30 July 1912 |

| Enthronement | 11 January 1869 |

| Born | Masako Ichijō (一条勝子) 9 May 1849 Heian-kyō, Japan |

| Died | 9 April 1914 (aged 64) Numazu, Japan |

| Burial | Fushimi Momoyama no Misasagi, Fushimi-ku, Kyoto, Japan |

| Spouse | |

| House | Imperial House of Japan |

| Father | Tadaka Ichijō |

| Mother | Tamiko Shinbata |

| Religion | Shinto |

Early life

Born Masako Ichijō (一条勝子, Ichijō Masako), Shōken was the third daughter of Tadaka Ichijō, former Minister of the Left and head of the Ichijō branch of the Fujiwara clan. Her official mother was a daughter of Prince Fushimi Kuniie, while her biological mother was Tamiko Shinbata, daughter of a doctor from the Ichijō family.

As a child, Princess Masako was somewhat of a prodigy; she was able to read poetry from the Kokin Wakashū by age four and had composed some waka verses of her own by age five. By age seven, she was able to read some texts in classical Chinese, with some assistance, and was studying Japanese calligraphy. By age twelve, she had studied the koto and was fond of Noh drama. She had also studied ikebana and the Japanese tea ceremony. Unusually for the time, she had also been vaccinated against smallpox. The major obstacle to her eligibility to be empress consort was the fact that she was three years older than Emperor Meiji, but this issue was resolved by changing her official birth date from 1849 to 1850.[1]

She became engaged to Emperor Meiji on 2 September 1867 and she adopted the given name Haruko (美子), which was intended to reflect her diminutive size and serene beauty. The Tokugawa Bakufu promised 15,000 ryō in gold for the wedding, and assigned her an annual income of 500 koku, but as the Meiji Restoration occurred before the wedding could be completed, the promised amounts were never delivered. The wedding was delayed partly due to periods of mourning for Emperor Kōmei, and for her brother Ichijō Saneyoshi, and due to political disturbances around Kyoto in 1867 and 1868. The wedding was finally officially celebrated on 11 January 1869.[1]

She was the first imperial consort to receive the title of both nyōgō and of kōgō (literally, the emperor's wife, translated as "empress consort"), in several hundred years.

Although she was the first Japanese empress consort to play a public role, it soon became clear that Empress Haruko was unable to bear children. Emperor Meiji had fifteen children by five official ladies-in-waiting. As it had long been the custom in Japanese monarchy, she adopted Yoshihito, her husband's eldest son by one of her husband's concubines (in this specific case, Lady Yanagihara Naruko). Yoshihito thus became the official heir to the throne, and at Emperor Meiji's death, succeeded him as Emperor Taishō.

Empress Consort

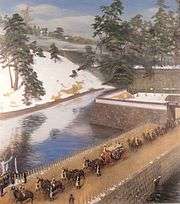

The Empress departed from Kyoto on 8 November 1869 for the new capital of Tokyo.[2] In a break from tradition, Emperor Meiji insisted that she, as well as the senior ladies-in-waiting, attend the educational lectures given to the Emperor on a regular basis about conditions in Japan, as well as developments in overseas nations.[3]

On 30 July 1886, the Empress attended the graduation ceremony of the Peeresses School in Western clothing, and on 10 August, she received foreign guests in Western clothing for the first time when hosting a Western Music concert with the Emperor.[4] From this point onward, the Empress and her entourage wore only Western style clothes in public and in January 1887 she issued a memorandum on the subject, contending that traditional Japanese dress was not only unsuited to modern life, but that in fact, Western style dress was closer than the kimono to clothes worn by Japanese women in ancient times.[5]

In the diplomatic field, the Empress hosted the wife of former US President Ulysses S. Grant during his visit to Japan, and was also present for the Emperor's meetings with Hawaiian King Kalākaua in 1881. Later that same year, she helped host the visit of the sons of future British King Edward VII, Prince Albert Victor and Prince George (the future George V), who presented her with a pair of pet wallabies from Australia.[6]

The Empress accompanied her husband to Yokosuka, Kanagawa on 26 November 1886 to observe the new Imperial Japanese Navy cruisers Naniwa and Takachiho firing torpedoes and performing other maneuvers. From 1887, she was often at the Emperor's side, in his official visits to schools, factories, and even Army maneuvers.[7] When Emperor Meiji fell ill in 1888, she took his place in welcoming envoys from Siam, launching warships and visiting Tokyo Imperial University.[8]

In 1889, she accompanied Emperor Meiji on his official visit to Nagoya and Kyoto. While the Emperor continued on to visit naval bases at Kure and Sasebo, she went to Nara, to worship at the principal Shinto shrines.[9]

Known throughout her reign for her support of charity work, and of women's education, during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–95), the Empress also worked for the establishment of the Japanese Red Cross Society. Especially concerned about Red Cross activities in peacetime, she created a fund for the International Red Cross, which was later named "The Empress Shōken Fund". It is presently used for international welfare activities. During the war, after the Emperor moved his military headquarters from Tokyo to Hiroshima to be closer to the lines of communications with his troops, the Empress, traveling together with his two favorite concubines, joined him in Hiroshima from March 1895. While in Hiroshima, she insisted on visiting hospitals, where wounded soldiers were recovering, every other day during her stay.[10]

Empress Dowager

On the death of Emperor Meiji in 1912, she was granted the title Empress Dowager (皇太后, Kōtaigō) by Emperor Taishō.

She died in 1914 at the Imperial Villa in Numazu, Shizuoka, and was buried in the East Mound of the Fushimi Momoyama Ryo in Fushimi, Kyoto, next to Emperor Meiji. Her soul was enshrined in Meiji Shrine in Tokyo. On 9 May 1914, she received the posthumous name Shōken Kōtaigō.[11]

The railway-carriage of the empress, as well as that of Emperor Meiji, can be seen today in the Meiji Mura Museum, in Inuyama, Aichi prefecture.

Titles and styles

| Styles of Empress Shōken | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | Her Imperial Majesty |

| Spoken style | Your Imperial Majesty |

- 9 May 1849 – 11 January 1869: Lady Masako Ichijō

- 11 January 1869 – 30 July 1912: Her Imperial Majesty The Empress

- 30 July 1912 – 9 April 1914: Her Imperial Majesty The Empress Dowager

- Posthumous title: Her Majesty Empress Shōken

Honours

National

- Grand Cordon of the Order of the Precious Crown - 1 November 1888

Foreign

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Empress Shōken[13] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Japanese empresses

- Ōmiya Palace

Notes

- Keene, Donald. (2005). Emperor of Japan:Meiji and His World, pp. 106-108.

- Keene, p. 188.

- Keene, p. 202.

- Donald Keene, Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912, 2010

- Keene, p. 404.

- Keene, pp. 350-351.

- Keene, p. 411.

- Keene, pp. 416.

- Keene, p. 433.

- Keene, p. 502.

- 大正3年宮内省告示第9号 (Imperial Household Ministry's 9th announcement in 1914)

- Royal Thai Government Gazette (11 February 1900). "บอกอรรคราชทูตสยาม เรื่องเฝ้าถวายเครื่องราชอิสริยาภรณ์เอมเปรสกรุงญี่ปุ่นถวายเครื่องราชอิสริยาภรณ์ บรมมหาจักรีวงษ์ฝ่ายใน ซึ่งสมเด็จพระบรมราชินีนารถมีพระราชเสาวณีย์โปรดเกล้า ฯ ให้เชิญมาถวายเอมเปรสญี่ปุ่น" (PDF) (in Thai). Retrieved 2019-05-08. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Genealogy". Reichsarchiv (in Japanese). Retrieved 28 October 2017.

References

- Fujitani, Takashi. (1998). Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan.. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20237-5; OCLC 246558189—Reprint edition, 1998. ISBN 0-520-21371-8

- Hoyt, Edwin P. (1992). Hirohito: The Emperor and the Man. New York: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-94069-0; OCLC 23766658

- Keene, Donald. (2002). Emperor Of Japan: Meiji And His World, 1852-1912. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12340-2; OCLC 237548044

- Lebra, Sugiyama Takie. (1996). Above the Clouds: Status Culture of the Modern Japanese Nobility. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20237-5; OCLC 246558189

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Empress Shōken. |

- Meiji Jingu | Empress Shoken

- The Empress Shoken Fund

- Red Cross | Empress Shoken Fund: Supporting Red Cross Red Crescent work for 100 years

| Japanese royalty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Eishō |

Empress consort of Japan 1869–1912 |

Succeeded by Teimei |