Ethel Moorhead

Ethel Agnes Mary Moorhead (28 August 1869 – 4 March 1955) was a British suffragette and painter[1] and was the first suffragette in Scotland to be forcibly-fed.

Ethel Moorhead | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Ethel Agnes Mary Moorhead August 28, 1869 Maidstone, Kent, England |

| Died | March 4, 1955 Blackrock, Dublin, Ireland |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupation | Painter, Suffragette |

Early life

Moorhead was born on 28 August 1869 in Maidstone, Kent. She was one of six children of Brigadier Surgeon George Alexander Moorhead, an army surgeon of Irish birth, and his wife, Margaret Humphrys (1833–1902), an Irish woman of French-Huguenot ancestry.[2] Her older sister Alice Moorhead (1868-1910) was a pioneer of female medicine, trained as a surgeon and physician.[3]

Her father was posted with the Berkshire Regiment to Afghanistan as army surgeon in 1870, and she would have seen little of him in her early years.[4]. Her father settled in Dundee in 1902[5] to be closer to Alice and her newly created Dundee Women's Hospital. After training as an artist in Paris under Mucha and in Whistler's studio, Ethel returned to care for him from 1908 (after Alice married). After her father died in 1911, Ethel moved to Edinburgh[4].

Suffragette campaigning

Moorhead made her maiden speech at a Dundee Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) meeting in March 1910, in December she threw an egg at Winston Churchill when he was holding a meeting in Dundee[4]. In 1911 the Dundee branch of the Women's Freedom League congratulated her on becoming Dundee's first tax-resister[4].

Moorhead used a string of aliases (Mary Humphreys, Edith Johnston, Margaret Morrison), and carried out various acts of militancy both north and south of the border. They included smashing two windows in London, attacking a showcase at the Wallace Monument near Stirling, and throwing cayenne pepper at a police constable, as well as wrecking police cells, and carrying out several arson attacks. In October 1912 after being ejected from a meeting in Synod Hall, Edinburgh Moorhead returned to attack the male lecturer with a dog whip for ejecting her[4]. She was arrested under her own name and was fined £1, this fine was paid so Moorhead never went to prison for this act[4]. Early in 1913, she tried to write to Arabella Scott about an incident of an amorous approach by inebriated prison doctor, which she feared would be used as propaganda. The Dundee Gaol governor did not release it.[6] On 23 July 1913, with Dorothea Chalmers Smith, Moorhead (in the alias Margaret Morrison) attempted to set fire to a house at 6 Park Gardens in Glasgow, but they were caught at the scene and the firefighters found flammable materials [7] and a postcard bearing the words: 'A protest against Mrs Pankhurst's re-arrest'.[6] She held no formal position in the WSPU, but achieved great personal notoriety.

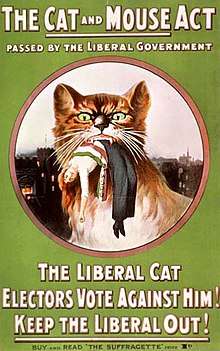

Moorhead was imprisoned several times and released under the "Cat and Mouse Act" of 1913[4]. She became the first Scottish suffragette to be forcibly fed, while imprisoned in Calton Jail, Edinburgh under the care of Dr Hugh Ferguson Watson[4]. Having become seriously ill with double pneumonia, she was released into the care of Dr Grace Cadell, a fellow activist in the suffrage movement. Her experience – duly related to the press – caused much protest at the cruelty involved.[8]

Moorhead had been given a Hunger Strike Medal 'for Valour' by WSPU.

This did not stop her activity, however, and along with her friend Fanny Parker she was arrested in July 1914, for trying to blow up the Burns Cottage in Alloway.[9]

Other campaigning and later life

During the First World War, Moorhead took on additional organisational responsibilities. Together with Fanny Parker, she helped run the Women's Freedom League (WFL) National Service Organisation, encouraging women to find appropriate work.

In the 1920s, she traveled in Europe and edited a quarterly arts journal, which published work by, among others, James Joyce, Ezra Pound and Ernest Hemingway. She married the writer Ernest Walsh, whom she outlived. She died in Dublin in 1955.[10]

A commemorative plaque has been placed close to the site of her home in Dundee.[11]

See also

External links

- "Biographical Sketches of Leading Figures in the Women's Suffrage Movement Around the Time of the Edinburgh Procession and Women's Demonstration of 1909". edinburghmuseums.org.uk. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- "Stories from The Scotsman – Scotland's forgotten sisters". electricscotland.com. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

References

- "Ethel Moorhead" (PDF). Dictionary of National Biography. 2004. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- Leneman, Leah (2004). "Moorhead, Ethel Agnes Mary" (PDF). Oxford Index. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- Biographical Dictionary of Scottish Women

- Leneman, Leah (1993). Martyrs in Our Midst: Dundee, Perth and the Forcible Feeding of Suffragettes. University of Stirling Library: Stevenson, Printers. pp. 15–19. ISBN 0-900019-29-8.

- Dundee Post Office Directory 1902

- Diane, Atkinson (2018). Rise up, women! : the remarkable lives of the suffragettes. London: Bloomsbury. p. 471. ISBN 9781408844045. OCLC 1016848621.

- "Introduction to Women's Suffrage in Scotland". www.scan.org.uk. Retrieved 9 February 2019.

- "Force-feeding Case Studies – Ethel Moorhead, Suffragette". johndclare.net. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- O’Brien, Megan. "Suffragettes and Suffragists in Scotland – Ethel Moorhead" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- "Ethel Moorhead". dundeewomenstrail.org.uk. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

.jpg)