Actor

An actor is a person who portrays a character in a performance (also actress; see below).[1] The actor performs "in the flesh" in the traditional medium of the theatre or in modern media such as film, radio, and television. The analogous Greek term is ὑποκριτής (hupokritḗs), literally "one who answers".[2] The actor's interpretation of their role—the art of acting—pertains to the role played, whether based on a real person or fictional character. This can also be considered an "actor's role," which was called this due to scrolls being used in the theaters. Interpretation occurs even when the actor is "playing themselves", as in some forms of experimental performance art.

Formerly, in ancient Greece and Rome, the medieval world, and the time of William Shakespeare, only men could become actors, and women's roles were generally played by men or boys.[3] While Ancient Rome did allow female stage performers, only a small minority of them were given speaking parts. The commedia dell’arte of Italy, however, allowed professional women to perform early on: Lucrezia Di Siena, whose name is on a contract of actors from 10 October 1564, has been referred to as the first Italian actress known by name, with Vincenza Armani and Barbara Flaminia as the first primadonna's and the first well documented actresses in Italy (and Europe). [4] After the English Restoration of 1660, women began to appear on stage in England. In modern times, particularly in pantomime and some operas, women occasionally play the roles of boys or young men.[5]

History

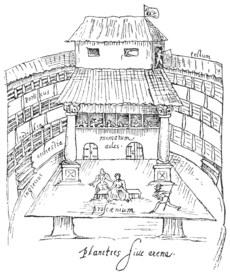

The first recorded case of a performing actor occurred in 534 BC (though the changes in calendar over the years make it hard to determine exactly) when the Greek performer Thespis stepped onto the stage at the Theatre Dionysus to become the first known person to speak words as a character in a play or story. Before Thespis' act, Grecian stories were only expressed in song, dance, and in third person narrative. In honor of Thespis, actors are commonly called Thespians. The exclusively male actors in the theatre of ancient Greece performed in three types of drama: tragedy, comedy, and the satyr play.[6] Western theatre developed and expanded considerably under the Romans. The theatre of ancient Rome was a thriving and diverse art form, ranging from festival performances of street theatre, nude dancing, and acrobatics, to the staging of situation comedies, to high-style, verbally elaborate tragedies.

As the Western Roman Empire fell into decay through the 4th and 5th centuries, the seat of Roman power shifted to Constantinople and the Byzantine Empire. Records show that mime, pantomime, scenes or recitations from tragedies and comedies, dances, and other entertainments were very popular. From the 5th century, Western Europe was plunged into a period of general disorder. Small nomadic bands of actors traveled around Europe throughout the period, performing wherever they could find an audience; there is no evidence that they produced anything but crude scenes.[7] Traditionally, actors were not of high status; therefore, in the Early Middle Ages, traveling acting troupes were often viewed with distrust. Early Middle Ages actors were denounced by the Church during the Dark Ages, as they were viewed as dangerous, immoral, and pagan. In many parts of Europe, traditional beliefs of the region and time meant actors could not receive a Christian burial.

In the Early Middle Ages, churches in Europe began staging dramatized versions of biblical events. By the middle of the 11th century, liturgical drama had spread from Russia to Scandinavia to Italy. The Feast of Fools encouraged the development of comedy. In the Late Middle Ages, plays were produced in 127 towns. These vernacular Mystery plays often contained comedy, with actors playing devils, villains, and clowns.[8] The majority of actors in these plays were drawn from the local population. Amateur performers in England were exclusively male, but other countries had female performers.

There were several secular plays staged in the Middle Ages, the earliest of which is The Play of the Greenwood by Adam de la Halle in 1276. It contains satirical scenes and folk material such as faeries and other supernatural occurrences. Farces also rose dramatically in popularity after the 13th century. At the end of the Late Middle Ages, professional actors began to appear in England and Europe. Richard III and Henry VII both maintained small companies of professional actors. Beginning in the mid-16th century, Commedia dell'arte troupes performed lively improvisational playlets across Europe for centuries. Commedia dell'arte was an actor-centred theatre, requiring little scenery and very few props. Plays were loose frameworks that provided situations, complications, and outcome of the action, around which the actors improvised. The plays used stock characters. A troupe typically consisted of 13 to 14 members. Most actors were paid a share of the play's profits roughly equivalent to the sizes of their roles.

Renaissance theatre derived from several medieval theatre traditions, such as the mystery plays, "morality plays", and the "university drama" that attempted to recreate Athenian tragedy. The Italian tradition of Commedia dell'arte, as well as the elaborate masques frequently presented at court, also contributed to the shaping of public theatre. Since before the reign of Elizabeth I, companies of players were attached to households of leading aristocrats and performed seasonally in various locations. These became the foundation for the professional players that performed on the Elizabethan stage.

The development of the theatre and opportunities for acting ceased when Puritan opposition to the stage banned the performance of all plays within London. Puritans viewed the theatre as immoral. The re-opening of the theatres in 1660 signaled a renaissance of English drama. English comedies written and performed in the Restoration period from 1660 to 1710 are collectively called "Restoration comedy". Restoration comedy is notorious for its sexual explicitness. At this point, women were allowed for the first time to appear on the English stage, exclusively in female roles. This period saw the introduction of the first professional actresses and the rise of the first celebrity actors.

19th century

In the 19th century, the negative reputation of actors was largely reversed, and acting became an honored, popular profession and art.[9] The rise of the actor as celebrity provided the transition, as audiences flocked to their favorite "stars". A new role emerged for the actor-managers, who formed their own companies and controlled the actors, the productions, and the financing.[10] When successful, they built up a permanent clientele that flocked to their productions. They could enlarge their audience by going on tour across the country, performing a repertoire of well-known plays, such as those by Shakespeare. The newspapers, private clubs, pubs, and coffee shops rang with lively debates evaluating the relative merits of the stars and the productions. Henry Irving (1838-1905) was the most successful of the British actor-managers.[11] Irving was renowned for his Shakespearean roles, and for such innovations as turning out the house lights so that attention could focus more on the stage and less on the audience. His company toured across Britain, as well as Europe and the United States, demonstrating the power of star actors and celebrated roles to attract enthusiastic audiences. His knighthood in 1895 indicated full acceptance into the higher circles of British society.[12]

20th century

By the early 20th century, the economics of large-scale productions displaced the actor-manager model. It was too hard to find people who combined a genius at acting as well as management, so specialization divided the roles as stage managers and later theatre directors emerged. Financially, much larger capital was required to operate out of a major city. The solution was corporate ownership of chains of theatres, such as by the Theatrical Syndicate, Edward Laurillard, and especially The Shubert Organization. By catering to tourists, theaters in large cities increasingly favored long runs of highly popular plays, especially musicals. Big name stars became even more essential.[13]

Techniques

- Classical acting is a philosophy of acting that integrates the expression of the body, voice, imagination, personalizing, improvisation, external stimuli, and script analysis. It is based on the theories and systems of select classical actors and directors including Konstantin Stanislavski and Michel Saint-Denis.

- In Stanislavski's system, also known as Stanislavski's method, actors draw upon their own feelings and experiences to convey the "truth" of the character they portray. Actors puts themselves in the mindset of the character, finding things in common to give a more genuine portrayal of the character.

- Method acting is a range of techniques based on for training actors to achieve better characterizations of the characters they play, as formulated by Lee Strasberg. Strasberg's method is based upon the idea that to develop an emotional and cognitive understanding of their roles, actors should use their own experiences to identify personally with their characters. It is based on aspects of Stanislavski's system. Other acting techniques are also based on Stanislavski's ideas, such as those of Stella Adler and Sanford Meisner, but these are not considered "method acting".[14]

- Meisner technique requires the actor to focus totally on the other actor as though he or she is real and they only exist in that moment. This is a method that makes the actors in the scene seem more authentic to the audience. It is based on the principle that acting finds its expression in people's response to other people and circumstances. Is it based on Stanislavski's system.

As opposite sex

Formerly, in some societies, only men could become actors. In ancient Greece and ancient Rome[15] and the medieval world, it was considered disgraceful for a woman to go on stage; this belief persisted until the 17th century in Venice. In the time of William Shakespeare, women's roles were generally played by men or boys.[3]

When an eighteen-year Puritan prohibition of drama was lifted after the English Restoration of 1660, women began to appear on stage in England. Margaret Hughes is oft credited as the first professional actress on the English stage.[16] This prohibition ended during the reign of Charles II in part because he enjoyed watching actresses on stage.[17] Specifically, Charles II issued letters patent to Thomas Killigrew and William Davenant, granting them the monopoly right to form two London theatre companies to perform "serious" drama, and the letters patent were reissued in 1662 with revisions allowing actresses to perform for the first time.[18]

The first occurrence of the term actress was in 1608 according to the OED and is ascribed to Middleton. In the 19th century, many viewed women in acting negatively, as actresses were often courtesans and associated with promiscuity. Despite these prejudices, the 19th century also saw the first female acting "stars", most notably Sarah Bernhardt.[19]

In Japan, onnagata, or men taking on female roles, were used in kabuki theatre when women were banned from performing on stage during the Edo period; this convention continues. In some forms of Chinese drama such as Beijing opera, men traditionally performed all the roles, including female roles, while in Shaoxing opera women often play all roles, including male ones.[20]

In modern times, women occasionally played the roles of boys or young men. For example, the stage role of Peter Pan is traditionally played by a woman, as are most principal boys in British pantomime. Opera has several "breeches roles" traditionally sung by women, usually mezzo-sopranos. Examples are Hansel in Hänsel und Gretel, Cherubino in The Marriage of Figaro and Octavian in Der Rosenkavalier.

Women playing male roles are uncommon in film, with notable exceptions. In 1982, Stina Ekblad played the mysterious Ismael Retzinsky in Fanny and Alexander, and Linda Hunt received the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for playing Billy Kwan in The Year of Living Dangerously. In 2007, Cate Blanchett was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for playing Jude Quinn, a fictionalized representation of Bob Dylan in the 1960s, in I'm Not There.

In the 2000s, women playing men in live theatre is particularly common in presentations of older plays, such as Shakespearean works with large numbers of male characters in roles where gender is inconsequential.[5]

Having an actor dress as the opposite sex for comic effect is also a long-standing tradition in comic theatre and film. Most of Shakespeare's comedies include instances of overt cross-dressing, such as Francis Flute in A Midsummer Night's Dream. The movie A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum stars Jack Gilford dressing as a young bride. Tony Curtis and Jack Lemmon famously posed as women to escape gangsters in the Billy Wilder film Some Like It Hot. Cross-dressing for comic effect was a frequently used device in most of the Carry On films. Dustin Hoffman and Robin Williams have each appeared in a hit comedy film (Tootsie and Mrs. Doubtfire, respectively) in which they played most scenes dressed as a woman.

Occasionally, the issue is further complicated, for example, by a woman playing a woman acting as a man—who then pretends to be a woman, such as Julie Andrews in Victor/Victoria, or Gwyneth Paltrow in Shakespeare in Love. In It's Pat: The Movie, film-watchers never learn the gender of the androgynous main characters Pat and Chris (played by Julia Sweeney and Dave Foley). Similarly, in the aforementioned example of The Marriage of Figaro, there is a scene in which Cherubino (a male character portrayed by a woman) dresses up and acts like woman; the other characters in the scene are aware of a single level of gender role obfuscation, while the audience is aware of two levels.

A few modern roles are played by a member of the opposite sex to emphasize the gender fluidity of the role. Edna Turnblad in Hairspray was played by Divine in the 1988 original film, Harvey Fierstein in the Broadway musical, and John Travolta in the 2007 movie musical. Eddie Redmayne was nominated for an Academy Award for playing Lili Elbe (a trans woman) in 2015's The Danish Girl.[21]

The term actress

In contrast to Ancient Greek theatre, Ancient Roman theatre did allow female performers. While the majority of them were seldom employed in speaking roles but rather for dancing, there was a minority of actresses in Rome employed in speaking roles, and also those who achieved wealth, fame and recognition for their art, such as Eucharis, Dionysia, Galeria Copiola and Fabia Arete, and they also formed their own acting guild, the Sociae Mimae, which was evidently quite wealthy. [22] The profession seemingly died out in late antiquity.

While women did not begin to perform onstage in England until the second half of the 17th-century, they did appear in Italy, Spain and France from the late 16th-century onward. Lucrezia Di Siena, whose name is on an acting contract in Rome from 10 October 1564, has been referred to as the first Italian actress known by name, with Vincenza Armani and Barbara Flaminia as the first primadonnas and the first well documented actresses in Italy (and Europe). [4]

After 1660 in England, when women first started to appear on stage, the terms actor or actress were initially used interchangeably for female performers, but later, influenced by the French actrice, actress became the commonly used term for women in theater and film. The etymology is a simple derivation from actor with -ess added.[23] When referring to groups of performers of both sexes, actors is preferred.[24] Actor is also used before the full name of a performer as a gender-specific term.

Within the profession, the re-adoption of the neutral term dates to the post-war period of the 1950 and '60s, when the contributions of women to cultural life in general were being reviewed.[25] When The Observer and The Guardian published their new joint style guide in 2010, it stated "Use ['actor'] for both male and female actors; do not use actress except when in name of award, e.g. Oscar for best actress".[24] The guide's authors stated that "actress comes into the same category as authoress, comedienne, manageress, 'lady doctor', 'male nurse' and similar obsolete terms that date from a time when professions were largely the preserve of one sex (usually men)." (See male as norm.) "As Whoopi Goldberg put it in an interview with the paper: 'An actress can only play a woman. I'm an actor – I can play anything.'"[24] The UK performers' union Equity has no policy on the use of "actor" or "actress". An Equity spokesperson said that the union does not believe that there is a consensus on the matter and stated that the "...subject divides the profession".[24] In 2009, the Los Angeles Times stated that "Actress" remains the common term used in major acting awards given to female recipients[26] (e.g., Academy Award for Best Actress).

With regard to the cinema of the United States, the gender-neutral term "player" was common in film in the silent film era and the early days of the Motion Picture Production Code, but in the 2000s in a film context, it is generally deemed archaic. However, "player" remains in use in the theatre, often incorporated into the name of a theatre group or company, such as the American Players, the East West Players, etc. Also, actors in improvisational theatre may be referred to as "players".[27]

.jpg)

Pay equity

In 2015, Forbes reported that "...just 21 of the 100 top-grossing films of 2014 featured a female lead or co-lead, while only 28.1% of characters in 100 top-grossing films were female...".[28] "In the U.S., there is an "industry-wide [gap] in salaries of all scales. On average, white women earn 78 cents to every dollar a white man makes, while Hispanic women earn 56 cents to a white male's dollar, Black women 64 cents and Native American women just 59 cents to that."[28] Forbes' analysis of US acting salaries in 2013 determined that the "...men on Forbes' list of top-paid actors for that year made 21/2 times as much money as the top-paid actresses. That means that Hollywood's best-compensated actresses made just 40 cents for every dollar that the best-compensated men made."[29][30][31]

Types

Actors working in theatre, film, television, and radio have to learn specific skills. Techniques that work well in one type of acting may not work well in another type of acting.

In theatre

To act on stage, actors need to learn the stage directions that appear in the script, such as "Stage Left" and "Stage Right". These directions are based on the actor's point of view as he or she stands on the stage facing the audience. Actors also have to learn the meaning of the stage directions "Upstage" (away from the audience) and "Downstage" (towards the audience)[32] Theatre actors need to learn blocking, which is "...where and how an actor moves on the stage during a play". Most scripts specify some blocking. The Director also gives instructions on blocking, such as crossing the stage or picking up and using a prop.[32]

Some theater actors need to learn stage combat, which is simulated fighting on stage. Actors may have to simulate hand-to-hand [fighting] or sword[-fighting]. Actors are coached by fight directors, who help them learn the choreographed sequence of fight actions. [32]

In film

Silent films

From 1894 to the late 1920s, movies were silent films. Silent film actors emphasized body language and facial expression, so that the audience could better understand what an actor was feeling and portraying on screen. Much silent film acting is apt to strike modern-day audiences as simplistic or campy. The melodramatic acting style was in some cases a habit actors transferred from their former stage experience. Vaudeville theatre was an especially popular origin for many American silent film actors.[33] The pervading presence of stage actors in film was the cause of this outburst from director Marshall Neilan in 1917: "The sooner the stage people who have come into pictures get out, the better for the pictures." In other cases, directors such as John Griffith Wray required their actors to deliver larger-than-life expressions for emphasis. As early as 1914, American viewers had begun to make known their preference for greater naturalness on screen.[34]

Pioneering film directors in Europe and the United States recognized the different limitations and freedoms of the mediums of stage and screen by the early 1910s. Silent films became less vaudevillian in the mid-1910s, as the differences between stage and screen became apparent. Due to the work of directors such as D W Griffith, cinematography became less stage-like, and the then-revolutionary close-up shot allowed subtle and naturalistic acting. In America, D.W. Griffith's company Biograph Studios, became known for its innovative direction and acting, conducted suit the cinema rather than the stage. Griffith realized that theatrical acting did not look good on film and required his actors and actresses to go through weeks of film acting training.[35]

Lillian Gish has been called film's "first true actress" for her work in the period, as she pioneered new film performing techniques, recognizing the crucial differences between stage and screen acting. Directors such as Albert Capellani and Maurice Tourneur began to insist on naturalism in their films. By the mid-1920s many American silent films had adopted a more naturalistic acting style, though not all actors and directors accepted naturalistic, low-key acting straight away; as late as 1927, films featuring expressionistic acting styles, such as Metropolis, were still being released.[34]

According to Anton Kaes, a silent film scholar from the University of Wisconsin, American silent cinema began to see a shift in acting techniques between 1913 and 1921, influenced by techniques found in German silent film. This is mainly attributed to the influx of emigrants from the Weimar Republic, "including film directors, producers, cameramen, lighting and stage technicians, as well as actors and actresses".[36]

The advent of sound in film

Film actors have to learn to get used to and be comfortable with a camera being in front of them.[37] Film actors need to learn to find and stay on their "mark." This is a position on the floor marked with tape. This position is where the lights and camera focus are optimized. Film actors also need to learn how to prepare well and perform well on-screen tests. Screen tests are a filmed audition of part of the script.

Unlike theater actors, who develop characters for repeat performances, film actors lack continuity, forcing them to come to all scenes (sometimes shot in reverse of the order in which they ultimately appear) with a fully developed character already.[35]

"Since film captures even the smallest gesture and magnifies it..., cinema demands a less flamboyant and stylized bodily performance from the actor than does the theater." "The performance of emotion is the most difficult aspect of film acting to master: ...the film actor must rely on subtle facial ticks, quivers, and tiny lifts of the eyebrow to create a believable character."[35] Some theatre stars "...have made the theater-to-cinema transition quite successfully (Laurence Olivier, Glenn Close, and Julie Andrews, for instance), others have not..."[35]

In television

"On a television set, there are typically several cameras angled at the set. Actors who are new to on-screen acting can get confused about which camera to look into."[32] TV actors need to learn to use lav mics (Lavaliere microphones).[32] TV actors need to understand the concept of "frame". "The term frame refers to the area that the camera's lens is capturing."[32] Within the acting industry, there are four types of television roles one could land on a show. Each type varies in prominence, frequency of appearance, and pay. The first is known as a series regular—the main actors on the show as part of the permanent cast. Actors in recurring roles are under contract to appear in multiple episodes of a series. A co-star role is a small speaking role that usually only appears in one episode. A guest star is a larger role than a co-star role, and the character is often the central focus of the episode or integral to the plot.

In radio

Radio drama is a dramatized, purely acoustic performance, broadcast on radio or published on audio media, such as tape or CD. With no visual component, radio drama depends on dialogue, music and sound effects to help the listener imagine the characters and story: "It is auditory in the physical dimension but equally powerful as a visual force in the psychological dimension."[38]

Radio drama achieved widespread popularity within a decade of its initial development in the 1920s. By the 1940s, it was a leading international popular entertainment. With the advent of television in the 1950s, however, radio drama lost some of its popularity, and in some countries has never regained large audiences. However, recordings of OTR (old-time radio) survive today in the audio archives of collectors and museums, as well as several online sites such as Internet Archive.

As of 2011, radio drama has a minimal presence on terrestrial radio in the United States. Much of American radio drama is restricted to rebroadcasts or podcasts of programs from previous decades. However, other nations still have thriving traditions of radio drama. In the United Kingdom, for example, the BBC produces and broadcasts hundreds of new radio plays each year on Radio 3, Radio 4, and Radio 4 Extra. Podcasting has also offered the means of creating new radio dramas, in addition to the distribution of vintage programs.

The terms "audio drama"[39] or "audio theatre" are sometimes used synonymously with "radio drama" with one possible distinction: audio drama or audio theatre may not necessarily be intended specifically for broadcast on radio. Audio drama, whether newly produced or OTR classics, can be found on CDs, cassette tapes, podcasts, webcasts, and conventional broadcast radio.

Thanks to advances in digital recording and Internet distribution, radio drama is experiencing a revival.[40]

See also

- Bit part

- Body double

- Cameo appearance

- Cast member

- Character actor

- Child actor

- Commedia dell'arte

- Dramatis personæ

- Droll

- Extra (acting)

- Farce

- GOTE

- Kabuki

- Leading actor

- Lists of actors

- Matinee idol

- Meisner technique

- Mime artist

- Movie star

- Music hall

- Pantomime

- Pornographic film actor

- Practical Aesthetics

- Presentational and representational acting

- Supporting actor

- Understudy

- Vaudeville

- Voice acting

References

- "The dramatic world can be extended to include the 'author', the 'audience' and even the 'theatre'; but these remain 'possible' surrogates, not the 'actual' referents as such" (Elam 1980, 110).

- "Definition of actor".Hypokrites (related to our word for hypocrite) also means, less often, "to answer" the tragic chorus. See Weimann (1978, 2); see also Csapo and Slater, who offer translations of classical source material using the term hypocrisis (acting) (1994, 257, 265–267).

- Neziroski, Lirim (2003). "narrative, lyric, drama". Theories of Media :: Keywords Glossary :: multimedia. University of Chicago. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

For example, until the late 1600s, audiences were opposed to seeing women on stage, because of the belief stage performance reduced them to the status of showgirls and prostitutes. Even Shakespeare's plays were performed by boys dressed in drag.

- Giacomo Oreglia (2002). Commedia dell'arte. Ordfront. ISBN 91-7324-602-6

- JULIET DUSINBERRE. "Boys Becoming Women in Shakespeare's Plays" (PDF). S-sj.org\accessdate=22 October 2017.

- Brockett and Hildy (2003, 15–19).

- Brockett and Hildy (2003, 75)

- Brockett and Hildy (2003, 86)

- Wilmeth, Don B.; Bigsby, C.W.E. (1998). The Cambridge history of American theatre. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 449–450. ISBN 978-0-521-65179-0.

- James Eli Adams, ed., Encyclopedia of the Victorian era (2004) 1:2-3.

- George Rowell, Theatre in the Age of Irving (Rowman & Littlefield, 1981).

- Jeffrey Richards (2007). Sir Henry Irving: A Victorian Actor and His World. A&C Black. p. 109. ISBN 9781852855918.

- Foster Hirsch, The Boys from Syracuse: The Shuberts' Theatrical Empire (Cooper Square Press, 2000).

- Guerrasio, Jason. (2014-12-19) What It Means To Be ‘Method’. Tribecafilminstitute.org. Retrieved on 2016-02-10.

- "BBC - Radio 4 - Woman's Hour -Women Actors in Ancient Rome". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- "Smallweed". The Guardian. 23 July 2005. Archived from the original on 22 April 2009.

"Whereas women's parts in plays have hitherto been acted by men in the habits of women ... we do permit and give leave for the time to come that all women's parts be acted by women," Charles II ordained in 1662. According to Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, the first actress to exploit this new freedom was Margaret Hughes, as Desdemona in Othello on December 8, 1660.

- "Women as actresses" (PDF). Notes and Queries. The New York Times. 18 October 1885. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

There seems no doubt that actresses did not perform on the stage till the Restoration, in the earliest years of which Pepys says for the first time he saw an actress upon the stage. Charles II, must have brought the usage from the Continent, where women had long been employed instead of boys or youths in the representation of female characters.

- Fisk, Deborah Payne (2001). "The Restoration Actress". In Owen, Susan J. A companion to restoration drama, pg. 73, (1. publ. ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0631219231.

- 'Studies in hysteria': actress and courtesan, Sarah Bernhardt and Mrs Patrick Campbell

- Richard Gunde, Culture and Customs of China (2002), page 63.

- Andrea Mandell, Can Eddie Redmayne nab Oscar No. 2?, December 20, 2015, USA Today

- Pat Easterling, Edith Hall: Greek and Roman Actors: Aspects of an Ancient Profession

- "actress, n.". Oxford English Dictionary (3 ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. November 2010.

Although actor refers to a person who acts regardless of gender, where this term "is increasingly preferred", actress remains in general use; actor is increasingly preferred for performers of both sexes as a gender-neutral term.

- Pritchard, Stephen (24 September 2011). "The readers' editor on... Actor or actress?". Theguardian.com. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Goodman, Lizbeth; Holledge, Julie (1998). The Routledge reader in gender and performance. New York: Routledge. pp. 8, . ISBN 0-415-16583-0.CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link)

- Linden, Sheri (18 January 2009). "From actor to actress and back again". Entertainment. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

It would be several decades before the word "actress" appeared – 1700, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, more than a century after the word "actor" was first used to denote a theatrical performer, supplanting the less professional-sounding "player."

- Spolin, Viola (1999). Improvisation for the Theater: A Handbook of Teaching and Directing Techniques (3rd ed.). Evanston, Ill: Northwestern Univ Press. pp. Introduction to the 3rd Edition. ISBN 0810140004. OCLC 41176682.

- Jennifer Lawrence Speaks Out On Making Less Than Male Co-Stars. Forbes.com (2015-10-13). Retrieved on 2016-02-10.

- Woodruff, Betsy. (2015-02-23) Gender wage gap in Hollywood: It's very, very wide. Slate.com. Retrieved on 2016-02-10.

- "How much do Hollywood campaigns for an Oscar cost?". Stephenfollows.com. Retrieved 2 May 2016.

- Female Movie Stars Experience Earnings Plunge After Age 34. Variety (2014-02-07). Retrieved on 2016-02-10.

- "Industry Tips". Archived from the original on March 26, 2014. Retrieved April 4, 2014.

- Lewis, John (2008). American Film: A History (First ed.). New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-97922-0.

- Brownlow, Kevin (1968). "Acting". The Parade's Gone By. University of California Press. pp. 344–353. ISBN 9780520030688.

- "Movies and Film". infoplease.com.

- Kaes, Anton (1990). "Silent Cinema". Monatshefte.

- "Auditions for Film: Movie Acting Tips and Techniques". Ace-your-audition.com. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- Tim Crook: Radio drama. Theory and practice Archived July 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. London; New York: Routledge, 1999, p. 8.

- Compare the entry to Hörspiel e.g. in: dict.cc – Deutsch-Englisch-Wörterbuch

- Newman, Barry (2010-02-25). "Return With Us to the Thrilling Days Of Yesteryear — Via the Internet". Wall Street Journal.

Sources

- Csapo, Eric, and William J. Slater. 1994. The Context of Ancient Drama. Ann Arbor: The U of Michigan P. ISBN 0-472-08275-2.

- Elam, Keir. 1980. The Semiotics of Theatre and Drama. New Accents Ser. London and New York: Methuen. ISBN 0-416-72060-9.

- Weimann, Robert. 1978. Shakespeare and the Popular Tradition in the Theater: Studies in the Social Dimension of Dramatic Form and Function. Ed. Robert Schwartz. Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-3506-2.

Further reading

- An Actor's Work by Constantin Stanislavski

- A Dream of Passion: The Development of the Method by Lee Strasberg (Plume Books, ISBN 0-452-26198-8, 1990)

- Sanford Meisner on Acting by Sanford Meisner (Vintage, ISBN 0-394-75059-4, 1987)

- Letters to a Young Actor by Robert Brustein (Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-00806-2, 2005).

- The Empty Space by Peter Brook

- The Technique of Acting by Stella Adler

External links

| Look up actor, actress, or player in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Screen Actors Guild (SAG): a union representing U. S. film and TV actors.

- Actors' Equity Association (AEA): a union representing U. S. theatre actors and stage managers.

- American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (AFTRA): a union representing U. S. television and radio actors and broadcasters (on-air journalists, etc.).

- British Actors' Equity: a trade union representing UK artists, including actors, singers, dancers, choreographers, stage managers, theatre directors and designers, variety and circus artists, television and radio presenters, walk-on and supporting artists, stunt performers and directors and theatre fight directors.

- Media Entertainment & Arts Alliance: an Australian/New Zealand trade union representing everyone in the media, entertainment, sports, and arts industries.