Einsatzkommando

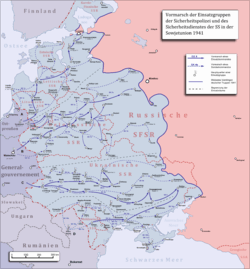

During World War II, the Nazi German Einsatzkommandos were a sub-group of the Einsatzgruppen (mobile killing squads) – up to 3,000 men total – usually composed of 500–1,000 functionaries of the SS and Gestapo, whose mission was to exterminate Jews, Polish intellectuals, Romani, and communists in the captured territories often far behind the advancing German front.[1][2] Einsatzkommandos, along with Sonderkommandos, were responsible for the systematic killing of Jews during the aftermath of Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. After the war several commanders were tried in the Einsatzgruppen trial, convicted, and executed.

German Einsatzkommando murder Polish civilians in Leszno, Poland on 21 October 1939 | |

| Formation | 1938 |

|---|---|

Membership | approximately 3,000 |

Founder | Reinhard Heydrich |

Organization of the Einsatzgruppen

Einsatzgruppen (German: special-ops units) were paramilitary groups originally formed in 1938 under the direction of Reinhard Heydrich – Chief of the SD, and Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police; SiPo). They were operated by the Schutzstaffel (SS).[3] The first Einsatzgruppen of World War II were formed in the course of the 1939 invasion of Poland. Then following a Hitler-Himmler directive, the Einsatzgruppen were re-formed in anticipation of the 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union.[4] The Einsatzgruppen were once again under the control of Reinhard Heydrich as Chief of the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA); and after his assassination, under the control of his successor, Ernst Kaltenbrunner.[5][6]

Hitler ordered the SD and the Security Police to suppress the threat of native resistance behind the Wehrmacht's fighting front. Heydrich met with General Eduard Wagner representing Wilhelm Keitel, who agreed to the activation, commitment, command, and jurisdiction of Security Police and SD units in the Wehrmacht's table of operations and equipment (TOE); in the rear operational areas, the Einsatzgruppen were to function in administrative sub-ordination to the field armies in order to effect the tasks assigned them by Heydrich. Their principal task (during the war), according to SS General Erich von dem Bach, at the Nuremberg Trials: "was the annihilation of the Jews, Gypsies, and Soviet political commissars". They were a key component in the implementation of the "Final Solution of the Jewish question" (German: Die Endlösung der Judenfrage) in the conquered territories. These killing units should be viewed in conjunction with the Holocaust.

The military commanders knew the task of the Einsatzgruppen. The Einsatzgruppen depended upon their sponsoring army commander for billet, food, and transportation. Relations between the regular army and the SiPo and the SD were close. Einsatzgruppen commanders reported that the understanding by Wehrmacht commanders of Einsatzgruppen tasks made their operations considerably easier.

For Operation Barbarossa (June 1941), initially four Einsatzgruppen were created, each numbering 500–990 men to comprise a total force of 3,000.[5] Each unit was attached to an army group: Einsatzgruppe A to Army Group North; Einsatzgruppe B to Army Group Center, Einsatzgruppe C to Army Group South, and Einsatzgruppe D to the 11th German Army. Led by SD, Gestapo, and Criminal Police (Kripo) officers, Einsatzgruppen included recruits from the regular police (Orpo), SD and Waffen-SS, augmented by uniformed volunteers from the local auxiliary police force.[7] When occasion demanded, German Army commanders bolstered the strength of the Einsatzgruppen with their own regular-army troops who assisted in rounding up and killing Jews of their own accord.[8]

The earliest Einsatzgruppen in occupied Poland

The first eight Einsatzgruppen of World War II were formed in 1939 for the invasion of Poland. They were composed of the Gestapo, Kripo and SD functionaries, and deployed during the classified Operation Tannenberg (codename for murder of Polish civilians) and the Intelligenzaktion lasting till the spring of 1940; followed by the German AB-Aktion which ended in late 1940. Long before the attack on Poland, the Nazis prepared a detailed list identifying more than 61,000 Polish targets by name,[9] with the help of German minority living in the Second Polish Republic. The list was printed as a 192-page-book called Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen (Special Prosecution Book–Poland), and composed only of names and birthdates. It included politicians, scholars, actors, intelligentsia, doctors, lawyers, nobility, priests, officers and numerous others – as the means at the disposal of the SS paramilitary death squads aided by Selbstschutz executioners.[10] By the end of 1939 already, they summarily killed around 50,000 Poles and Jews in the annexed territories, including over 1,000 POWs.[11][12][13][14]

The SS operational groups were assigned Roman numerals for the first time on 4 September 1939. Before that, their names were derived from the names of their places of origin in the German language.[15]

- Einsatzgruppe I or EG I–Wien (under the command of SS-Standartenführer Bruno Streckenbach),[15] deployed with the 14th Army

- Einsatzkommando 1/I: SS-Sturmbannführer Ludwig Hahn

- Einsatzkommando 2/I: SS-Sturmbannführer Bruno Müller

- Einsatzkommando 3/I: SS-Sturmbannführer Alfred Hasselberg

- Einsatzkommando 4/I: SS-Sturmbannführer Karl Brunner

- Einsatzgruppe II or EG II–Oppeln (under SS-Obersturmbannführer Emanuel Schäfer),[15] deployed with the 10th Army

- Einsatzkommando 1/II: SS-Obersturmbannführer Otto Sens

- Einsatzkommando 2/II: SS-Sturmbannführer Karl-Heinz Rux

- Einsatzgruppe III or EG III–Breslau (under SS-Obersturmbannführer und Regierungsrat Hans Fischer),[15] deployed with the 8th Army

- Einsatzkommando 1/III: SS-Sturmbannführer Wilhelm Scharpwinkel

- Einsatzkommando 2/III: SS-Sturmbannführer Fritz Liphardt

- Einsatzgruppe IV or EG IV–Dramburg (under SS-Brigadeführer Lothar Beutel,[15] replaced by Josef Albert Meisinger in October 1939) deployed with the 4th Army in Pomorze (see also EG-V)

- Einsatzkommando 1/IV: SS-Sturmbannführer und Regierungsrat Helmut Bischoff

- Einsatzkommando 2/IV: SS-Sturmbannführer und Regierungsrat Walter Hammer

- Einsatzgruppe V or EG V–Allenstein (under SS-Standartenfürer Ernst Damzog),[15] deployed with the 3rd Army

- Einsatzkommando 1/V: SS-Sturmbannführer und Regierungsrat Heinz Gräfe

- Einsatzkommando 2/V: SS-Sturmbannführer und Regierungsrat Robert Schefe

- Einsatzkommando 3/V: SS-Sturmbannführer und Regierungsrat Walter Albath

- Einsatzgruppe VI (under SS-Oberführer Erich Naumann), deployed in Wielkopolska area

- Einsatzkommando 1/VI: SS-Sturmbannführer Franz Sommer

- Einsatzkommando 2/VI: SS-Sturmbannführer Gerhard Flesch

- Einsatzgruppe z. b. V.[16] (under SS-Obergruppenführer Udo von Woyrsch and SS-Oberfürer Otto Rasch), deployed in Upper Silesia and Cieszyn Silesia

- Einsatzkommando 16 or EK–16 Danzig (under SS-Sturmbannführer Rudolf Tröger),[15] deployed in Pomerania (Polish: Pomorze) after the withdrawal of EG-IV and EG-V.[15] The Commando was involved in the massacres in Piaśnica known as "Pommern Katyń" between the fall of 1939 and spring of 1940 conducted in Piasnica Wielka (pictured). The civilian shooters belonged to Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz aiding EK–16. During that period approximately 12,000 to 16,000 Poles, Jews, Czechs, and Germans were murdered. Not to be confused with Einsatzkommando 16 of Einsatzgruppe E deployed in Croatia (see below)

Einsatzgruppe A

Einsatzgruppe A,[17] attached to the Army Group North, was formed in Gumbinnen in East Prussia on 23 June 1941. Stahlecker – its first commander – deployed the unit toward the Lithuanian border. His group consisted of 340 men from the Waffen-SS, 89 from the Gestapo, 35 from the SD, 133 from the Orpo, and 41 from the Kripo.[18] Soviet troops withdrew from the Lithuanian temporary capital Kaunas (Kovno) the day before, and the city was taken over by Lithuanians during the anti-Soviet uprising. On 25 June, the Einsatzgruppe A entered Kaunas with the forward units of the German army.[19]

- Commanders

- SS-Brigadeführer und Generalmajor der Polizei Dr. Franz Walter Stahlecker (22 June 1941–23 March 1942)

- SS-Brigadeführer und Generalmajor der Polizei Heinz Jost (29 March–2 September 1942)

- SS-Oberführer und Oberst der Polizei Dr. Humbert Achamer-Pifrader (10 September 1942–4 September 1943)

- SS-Oberführer Friedrich Panzinger (5 September 1943–6 May 1944)

- SS-Oberführer und Oberst der Polizei Dr. Wilhelm Fuchs (6 May–10 October 1944)

- Sonderkommando 1a

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Dr. Martin Sandberger (June 1941–1943)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Bernhard Baatz (1 August 1943–15 October 1944)

- Sonderkommando 1b

- SS-Oberführer und Oberst der Polizei Erich Ehrlinger (June–November 1941)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Walter Hoffmann (As Deputy) – (January–March 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Dr. Eduard Strauch (March–August 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Erich Isselhorst (30 June–1 October 1943)

- Einsatzkommando 1a

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Dr. Martin Sandberger (June 1942–1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Karl Tschierschky (1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Erich Isselhorst (November 1942 – June 1943)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Bernhard Baatz (June–August 1943)

- Einsatzkommando 1b

- SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Hermann Hubig (June–October 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Manfred Pechau (October–November 1942)

- Einsatzkommando 1c

- SS-Sturmbannführer Kurt Graaf (1 August-28 November 1942)

- Einsatzkommando 2

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Rudolf Batz (June–4 November 1941)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Dr. Eduard Strauch (4 November–2 December 1941)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Rudolf Lange (3 December 1941–1944)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Manfred Pechau (October 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Reinhard Breder (26 March 1943 – July 1943)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Oswald Poche (30 July 1943–2 March 1944)

- Einsatzkommando 3

- SS-Standartenführer Karl Jäger (June 1941–1 August 1943)

- SS-Oberführer und Oberst der Polizei Dr. Wilhelm Fuchs (15 September 1943–27 May 1944)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Hans-Joachim Böhme (11 May–July 1944)

Jäger Report

The Jäger Report is the most precise surviving chronicle of the activities of one Einsatzkommando. It is a tally sheet of the actions of Einsatzkommando 3 — a running total of their killings of 136,421 Jews (46,403 men 55,556 women, 34,464 children), 1,064 Communists, 653 persons with mental disabilities, and 134 others, from 2 July-1 December 1941. A second, major sweep occurred in 1942, before death camp killing replaced Einsatzkommando open-pit executions. Einsatzkommando 3 operated in the Kovno (Kaunas) district, west of Vilna (Vilnius) in contemporary Lithuania.(See also Rollkommando Hamann)

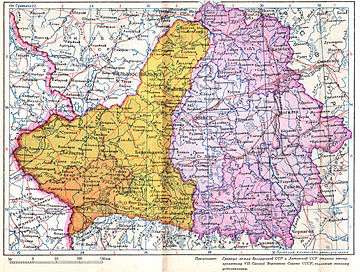

Einsatzgruppe B

The operational command of Einsatzgruppe B,[17] attached to the Army Group Center, was established under the command of Arthur Nebe a few days after the German attack on the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa. Einsatzgruppe B departed from the occupied city of Poznań (Posen) on 24 June 1941, with 655 men from the Security Police, Gestapo, Kripo, SD, Waffen-SS and the 2nd Company of Reserve Police Battalion 9.[2] On 30 June 1941 Himmler visited the newly formed Bezirk Bialystok district and pronounced that more forces were needed in the area, due to potential risks of partisan warfare. The chase after the Red Army's rapid retreat left behind a security vacuum, which required urgent deployment of additional personnel.[2]

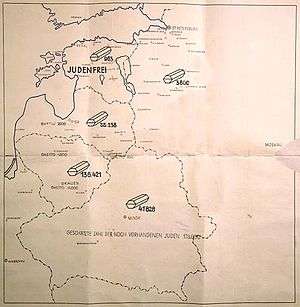

|

Płock (Schröttersburg) deployment location of Einsatzgruppe B, east of Chelmno extermination camp. Solid red line denotes the German–Soviet frontier – starting point for Operation Barbarossa.

Białystok

Vileyka

EG-A

EG-B

EG-C

EG-D

Map of the Einsatzgruppen operations with the location of the first shooting of Jewish women and children (along with the men) in Vileyka, July 30, 1941.

|

Scrambling to meet the "new threat", Gestapo headquarters in Zichenau (Ciechanów) formed a lesser known unit called Kommando SS Zichenau-Schroettersburg, which departed from the sub-station Schröttersburg (Płock) under the command of SS-Obersturmführer Hermann Schaper, with the mission to kill Jews, communists and the NKVD collaborators across the local villages and towns in the Bezirk. On 3 July additional formation of Schutzpolizei arrived in Białystok from the General Government. It was led by SS-Hauptsturmführer Wolfgang Birkner, veteran of Einsatzgruppe IV from the Polish Campaign of 1939. The relief unit, called Kommando Bialystok,[20] was sent in by SS-Obersturmbannfuhrer Eberhard Schöngarth on orders from the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA), due to reports of Soviet guerrilla activity in the area with Jews being of course immediately suspected of helping them out. On 10 July 1941, Schaper's unit was split into smaller Einsatzkommandos due to requirements of Operation Barbarossa.[21]

In addition to mass shootings, Einsatzgruppe B engaged in public hangings used as a terror tactic on the local population. An Einsatzgruppe B report, dated 9 October 1941, described one such hanging. Due to suspected partisan activity in the area around the settlement of Demidov, all males aged fifteen to fifty-five in Demidov were detained in a camp for screening. The screening produced seventeen people identified as 'partisans' and 'communists'. Thereafter, 400 local residents were assembled to watch the hanging of five members of the group; the rest were shot.[22]

On 14 November 1941, Nebe told Berlin that, up until then, 45,000 persons had been eliminated. A further report, dated 15 December 1942, established that the Einsatzgruppe B had shot a total of 134,298 people.[23] After 1943, the mass killings of Einsatzgruppe B diminished, and the unit was decommissioned in August 1944.

- Commanders

- SS-Gruppenführer und Generalmajor der Polizei Arthur Nebe (June–November 1941)

- SS-Brigadeführer und Generalmajor der Polizei Erich Naumann (November 1941 – March 1943)

- SS-Standartenführer Horst Böhme (12 March–28 August 1943)

- SS-Oberführer und Oberst der Polizei Erich Ehrlinger (28 August 1943 – April 1944)

- SS-Oberführer und Oberst der Polizei Heinrich Seetzen (28 April–August 1944)

- SS-Standartenführer Horst Böhme (12 August 1944)

Around 5 July 1941, Nebe consolidated Einsatzgruppe B near Minsk, establishing a headquarters and remaining there for some two months. The Gruppenführer determined that Sonderkommando 7a and Sonderkommando 7b and the Vorkommando Moskau would follow the Army Group Center, while Einsatzkommandos 8 and 9 clean up to the sides of the spearhead. In compliance, Einsatzkommando 8 reached Bialystok on 1 July, passed through Słonim and Baranowicze, and began systematic mass killing operations in modern-day southern Belarus (eastern Poland before World War II).[21]

On 5 August, Nebe moved his Einsatzgruppen command to Smolensk, where the Vorkommando Moskau was concentrated. On 6 August, Einsatzkommando 8 reached Minsk, remaining there until 9 September 1941. From Minsk, it reached Mogilev, which became its general headquarters, and from there Einsatzkommando 8 effected successive killings in Bobruisk, Gomel, Roslavl, and Klintsy systematically attacking the local Jewish communities, and killing the inhabitants.

Meanwhile, Einsatzkommando 9 was put to work; they had left Treuburg, in eastern Prussia, and reached Vilna on 2 July. Their main theater of mass killing operations were Grodno and Bielsk-Podlaski (Biala-Podlaska). On 20 July it moved its headquarters to Vitebsk, and then exterminated the citizens of Polotzk, Nevel, Lepel, and Surazh. The command progressed to Vtasma, and from there they killed the communities of Gshatsk and Mozhaisk in the Moscow vicinity. The Soviet counter-offensive forced the Einsatzkommando to withdraw to Vitebsk on 21 December 1941. Anticipating the fall of Moscow, the Vorkommando Moskau advanced to Maloyaroslavets, earlier captured by the Wehrmacht on 18 October 1941. In practice, Sonderkommandos 7a and 7b operated behind the vanguard of the army. The actions were fast, in order to prevent the Jews from escaping the advancing German Army. To the south and east of Smolensk and Minsk, the two Sonderkommandos left a wake of dead civilians, from Velikiye Luki, Kalinin, Orsha, Gomel, Chernigov and Orel, to Kursk.

- Sonderkommando 7a

Sonderkommando 7a led by Walter Blume, was attached to the 9th Army under General Adolf Strauß. SK 7a entered Vilna on 27 June and remained there until 3 July.[2] Soon Vilna was in the command sphere of Einsatzgruppe A, and Sonderkommando 7a was transferred to Kreva near Minsk. The Sonderkommando was active in Vilna, Nevel, Haradok, Vitebsk, Velizh, Rzhev, Vyazma, Kalinin, and Klintsy. It executed 1344 people.

- SS-Standartenführer Walter Blume (June–September 1941)

- SS-Standartenführer Eugen Steimle (September–December 1941)

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Kurt Matschke (December 1941 – February 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Albert Rapp (February 1942–28 January 1943)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Helmut Looss (June 1943 – June 1944)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Gerhard Bast (June–October/November 1944)

- Sonderkommando 7b

The Sonderkommando was active in Brest-Litovsk (see the Brześć Ghetto), Kobrin, Pruzhany, Slonim (the Słonim Ghetto), Baranovichi, Stowbtsy, Minsk (the Minsk Ghetto), Orsha, Klinzy, Briansk, Kursk, Tserigov, and Orel. It executed 6,788 people.

- SS-Sturmbannführer Günther Rausch (June 1941 – January/February 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Adolf Ott (February 1942 – January 1943)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Josef Auinger (July 1942 – January 1943)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Karl-Georg Rabe (January/February 1943 – October 1944)

- Sonderkommando 7c

See also Vorkommando Moskau

- SS-Sturmbannführer Friedrich-Wilhelm Bock (June 1942)

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Ernst Schmücker (June 1942 – 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Wilhelm Blühm (1942 – July 1943)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Hans Eckhardt (July–December 1943)

- Einsatzkommando 8

The Einsatzkommando was active in Volkovisk, Baranovichi, Babruysk, Lahoysk, Mogilev, and Minsk. It executed 74,740 people.

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Dr. Otto Bradfisch (June 1941–1 April 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Heinz Richter (1 April–September 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Erich Isselhorst (September–November 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Hans-Gerhard Schindhelm (7 November 1942 – October 1943)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Alfred Rendörffer (?)

- Einsatzkommando 9

The Einsatzkommando was active in Vilna (see the Vilna Ghetto), Grodno (the Grodno Ghetto), Lida, Bielsk-Podlaski, Nevel, Lepel, Surazh, Vyazma, Gzhatsk, Mozhaisk, Vitebsk (the Vitebsk Ghetto), Smolensk, and Varena. It executed 41,340 people.

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Alfred Filbert (June–20 October 1941)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Oswald Schäfer (October 1941 – February 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Wilhelm Wiebens (February 1942 – January 1943)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Dr. Friedrich Buchardt (January 1943 – October 1944)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Werner Kämpf (October 1943 – March 1944)

- Vorkommando Moskau

The Vorkommando—also known as Sonderkommando 7c—was to operate in Moscow, until it became apparent that Moscow would not fall; it was incorporated to Sonderkommando 7b, where it was active in Smolensk and executed 4,660 people.

- SS-Brigadeführer Professor Dr. Franz Six (20 June–20 August 1941)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Waldemar Klingelhöfer (August–September 1941)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Dr. Erich Körting (September–December 1941)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Friedrich Buchardt (December 1941 – January 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Friedrich-Wilhelm Bock (January–June 1942)

Einsatzgruppe C

The Einzatzgruppe C, as a whole, was attached to the Army Group South and executed 118,341 people.[17]

- SS-Brigadeführer und Generalmajor der Polizei Dr. Dr. Otto Rasch (June–October 1941)

- SS-Gruppenführer und Generalleutnant der Polizei Max Thomas (October 1941–29 April 1943)

- SS-Standartenführer Horst Böhme (6 September 1943 – March 1944)

- Einsatzkommando 4a

The Einsatzkommando was active in Lviv (see the Lwów Ghetto), Lutsk (the Łuck Ghetto), Rovno (Rovno ghetto), Zhytomyr, Pereyaslav, Yagotyn, Ivankov, Radomyshl, Lubny, Poltava, Kiev (see Babi Yar), Kursk, Kharkiv and executed 59,018 people.

- SS-Standartenführer Paul Blobel (June 1941–13 January 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Erwin Weinmann (13 January–27 July 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Eugen Steimle (August 1942–15 January 1943)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Friedrich Schmidt (January–February 1943)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Theodor Christensen (March–December 1943)

- Einsatzkommando 4b

The Einsatzkommando was active in Lviv, Tarnopol (modern Ternopil, see the Tarnopol Ghetto), Kremenchug, Poltava, Sloviansk, Proskurov, Vinnytsia, Kramatorsk, Gorlovka and Rostov. It executed 6,329 people.

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Günther Herrmann (June–October 1941)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Fritz Braune (2 October 1941–21 March 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Dr. Walter Hänsch (March–July 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer August Meier (July–November 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Friedrich Sühr (November 1942 – August 1943)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Waldemar Krause (August 1943 – January 1944)

- Einsatzkommando 5

The Einsatzkommando was active in Lviv (see the Lwów Ghetto), Brody, Dubno, Berdičhev, Skvyra and Kiev (Babi Yar). It executed more than 150,000 people.

- SS-Oberführer Erwin Schulz (June–August 1941) [24]

- SS-Sturmbannführer August Meier (September 1941 – January 1942)

- Einsatzkommando 6

The Einsatzkommando was active in Lviv, Zolochiv, Zhytomyr, Proskurov (modern Khmelnytskyi), Vinnytsia, Dnipropetrovsk, Kryvyi Rih, Stalino and Rostov. It executed 5,577 people.

- SS-Standartenführer Dr. Erhard Kröger (June–November 1941)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Robert Möhr (November 1941 – September 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Ernst Biberstein (September 1942 – May 1943)

- ?

- SS-Sturmbannführer Friedrich Sühr (August–November 1943)

Einsatzgruppe D

The Einsatzgruppe D, as a whole,[17] was attached to the 11th Army. It was established in June 1941 and operated until March 1943. Einsatzgruppe D conducted operations in northern Transylvania, Cernauti, Kishinev and across the Crimea. In March 1943 it was re-deployed in Ovruch as an anti-partisan unit called Kampfgruppe Bierkamp, named after its new commander Walther Bierkamp. The Einsatzgruppe D was responsible for the killing of over 91,728 people.[25]

- Commanders

- SS-Gruppenführer und Generalleutnant der Polizei Dr. Otto Ohlendorf (June 1941 – July 1942)

- SS-Brigadeführer und Generalmajor der Polizei Walther Bierkamp (July 1942 – March 1943)

- Einsatzkommando 10a

- SS-Oberführer und Oberst der Polizei Heinrich Seetzen (June 1941 – July 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Kurt Christmann (August 1942 – July 1943)

- Einsatzkommando 10b

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Alois Persterer (June 1941 – December 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Eduard Jedamzik (December 1942 – February 1943)

- Einsatzkommando 11a

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Paul Zapp (June 1941 – July 1942)

- Fritz Mauer (July–October 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Gerhard Bast (November–December 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Werner Hersmann (December 1942 – May 1943)

- Einsatzkommando 11b

- SS-Sturmbannführer Hans Unglaube (June–July 1941)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Bruno Müller (July–October 1941)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Werner Braune (October 1941 – September 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Paul Schultz (September 1942 – February 1943)

- Einsatzkommando 12

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Gustav Adolf Nosske (June 1941 – February 1942)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Dr. Erich Müller (February–October 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Günther Herrmann (October 1942 – March 1943)

Einsatzgruppe E

The Einsatzgruppe E was deployed in Croatia (i.e. in Yugoslavia) behind the 12th Army (Wehrmacht) in the area of Vinkovci (then Esseg), Sarajevo, Banja Luka, Knin, and Zagreb.

- Commanders

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Ludwig Teichmann (August 1941 – April 1943)

- SS-Standartenführer Günther Herrmann (April 1943–1944)

- SS-Oberführer und Oberst der Polizei Wilhelm Fuchs (October–November 1944)[26]

- Einsatzkommando 10b

- SS-Obersturmbannführer und Oberregierungsrat Joachim Deumling (March 1943 – January 1945)

- SS-Sturmbannführer Franz Sprinz (January–May 1945)

- Einsatzkommando 11a

- SS-Sturmbannführer und Regierungsrat Rudolf Korndörfer (May–September 1943)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Anton Fest (September 1943–1945)

- Einsatzkommando 15

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Willi Wolter (June 1943 – September 1944)

- Einsatzkommando 16

- SS-Obersturmbannführer und Oberregierungsrat Johannes Thümmler (July–September 1943)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Joachim Freitag (September 1943 – October 1944)

- Einsatzkommando Agram

- SS-Sturmbannführer und Regierungsrat Rudolf Korndörfer (September 1943)

Einsatzgruppe Serbien

- SS-Oberführer und Oberst der Polizei Wilhelm Fuchs (April 1941 – January 1942), Yugoslavia

- SS-Oberführer Emanuel Schäfer (January 1942)

Einsatzkommando Tunis

- Einsatzkommando headed by SS officer Walter Rauff in Tunis, North Africa.

Einsatzkommando Finnland

Officially the Einsatzkommando der Sicherheitspolizei und des SD beim AOK Norwegen, Befehlsstelle Finnland, Einsatzkommando Finnland was a German paramilitary unit active in northern Finland and northern Norway. Operating under the Reichssicherheitshauptamt, and Finnish Valpo security police, Einsatzkommando Finnland remained a secret until 2008.

Planned Einsatzkommando units

- Einsatzkommando-6 – planned for the United Kingdom and headed by Dr. Franz Six (Aborted. Six reassigned to special unit to be activated following the capture of Moscow).

- Einsatzkommando Ägypten – planned for Jewish residents in the Middle East, including Palestine.

Notes

- Thomas Urban, reporter of the Süddeutsche Zeitung; Polish text in Rzeczpospolita, Sept 1–2, 2001

- Rossino, Alexander B. (2003-11-01). ""Polish 'Neighbours' and German Invaders: Anti-Jewish Violence in the Białystok District during the Opening Weeks of Operation Barbarossa."". In Steinlauf, Michael C.; Polonsky, Antony (eds.). Polin: Studies in Polish Jewry Volume 16: Focusing on Jewish Popular Culture and Its Afterlife. The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. pp. 431–452. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1rmk6w.30. ISBN 978-1-909821-67-5. JSTOR j.ctv1rmk6w.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 405, 412.

- Kershaw 2008, pp. 598, 618.

- Longerich 2010, p. 185.

- Longerich 2012, pp. 470, 661.

- Browning 1998, pp. 10–12.

- Langerbein 2003, pp. 31–32.

- Digital version of the Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen (Special Prosecution Book-Poland) Archived 2013-12-17 at the Wayback Machine, at the Silesian Digital Library (Śląska Biblioteka Cyfrowa), Poland. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- Christopher R. Browning (2007). Poland, laboratory of racial policy. The Origins of the Final Solution. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 31–34. ISBN 978-0803259799. Retrieved June 20, 2012.

- Tadeusz Piotrowski (2007). Nazi Terror (Chapter 2). Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration With Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786429134. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- Richard Rhodes, Masters of Death: The SS-Einsatzgruppen and the Invention of the Holocaust, Bellona 2008

- Jochen Bohler, Jürgen Matthäus, Klaus-Michael Mallmann, Einsatzgruppen in Polen, Wissenschaftl. Buchgesell 2008.

- AB-Aktion, Shoah Resource Center, International Institute for Holocaust Research. Washington, DC.

- Piotr Semków, IPN Gdańsk (September 2006). "Kolebka (Cradle)" (PDF file, direct download: 3.44 MB). IPN Bulletin No. 8–9 (67–68), 152 Pages. Warsaw: Institute of National Remembrance: 42–50. ISSN 1641-9561. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- z. b. V. = zur besonderen Verwendung – "for special use".

- Ronald Headland (1992). Messages of Murder: A Study of the Reports of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the Security Service, 1941-1943. Tables of Killing Statistics: Einsatzgruppe A, B, C, and D. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press. pp. 98–101. ISBN 0838634184.

- Vadim Birstein (2013). Smersh: Stalin's Secret Weapon. Biteback Publishing. p. 236. ISBN 978-1849546898.

- Yitzhak Arad (2009). The Holocaust in the Soviet Union. University of Nebraska Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0803222700. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Tomasz Szarota (December 2–3, 2000). "Do we now know everything for certain? (translation)". Gazeta Wyborcza. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2011.

- (in Polish) Thomas Urban, "Poszukiwany Hermann Schaper", Rzeczpospolita, 01.09.01 Nr 204

- Headland 1992, pp. 57-58.

- University Center for International Studies (1982). Histoire Russe, Volume 9. University of Pittsburgh.

Up to 15 December 1942, Einsatzgruppe B reported executing a total of 134,298 persons (see Prestupleniia Belorussii, pp. 68-69), but the "bandits" included in these totals are probably incorporated in the German army reports.[29] These changes, largely the work of "Fremde Heere Ost" chief Colonel Reinhard Gehlen, included the granting of prisoner-of-war status to captured partisans and offered guerrilla deserters the option of enlistment in Soviet defector Gen. Andrei Vlasov's "Russian Army of Liberation." The relevant material is located on T-78/489/64750995144.

- NS-Archiv : Dokumente zum Nationalsozialismus : Erwin Schulz, Eidesstattliche Erklärung Archived 2016-03-06 at the Wayback Machine (in German)

- "Einsatzgruppe D. Organizational structure". The Holocaust Education and Archive Research Team. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 9, 2012.

- "Einsatzgruppe E". TenhumbergReinhard.de. Retrieved 6 August 2016.

References

- Browning, Christopher R. (1998) [1992]. Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0060995065.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Headland, Ronald (1992). Messages of Murder: A Study of the Reports of the Security Police and the Security Service. Associated University Presses. ISBN 0-8386-3418-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kershaw, Ian (2008). Hitler, the Germans, and the Final Solution. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12427-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Langerbein, Helmut (2003). Hitler's Death Squads: The Logic of Mass Murder. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-285-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Longerich, Peter (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Longerich, Peter (2012). Heinrich Himmler: A Life. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-959232-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Trials of War Criminals Before the Nurenberg Military Tribunals Under Control Council Law No. 10, Volume IV, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 35–36

- MacLean, French (1999). The Field Men: The SS Officers Who Led the Einsatzkommandos – the Nazi Mobile Killing Units, Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, ISBN 978-0764307546