Zolochiv

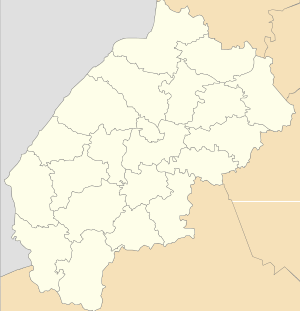

Zolochiv (Ukrainian: Золочів, Polish: Złoczów, Yiddish: זלאָטשאָוו, Zlotchov) is a small city of district significance in the Lviv Oblast of Ukraine, the administrative center of Zolochiv Raion. The city is located 60 kilometers east of Lviv along Highway H02 Lviv-Ternopil and the railway line Krasne-Ternopil. Its population is approximately 24,269 (2017 est.)[2], covering an area of 1,164 km2 (449 sq mi).

Zolochiv Золочів Złoczów | |

|---|---|

City of district significance | |

Downtown Zolochiv | |

Flag Coat of arms | |

Zolochiv  Zolochiv | |

| Coordinates: 49°48′26.97″N 24°54′11.02″E | |

| Country | |

| Oblast | |

| Raion | Zolochiv Raion |

| Founded | 1442 |

| Area | |

| • Total | 11.64 km2 (4.49 sq mi) |

| Population (2018) | |

| • Total | 24 278[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+02:00 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+03:00 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 80700 |

| Area codes | +380 3265 |

| Website | zolochiv-rada |

History

The site was occupied from AD 1180 under the name Radeche until the end of the 13th century when a wooden fort was constructed. This was burned in the 14th century during the invasion of the Crimean Tatars.

In 1442, the city was founded as Zolochiv, by John of Sienna, a Polish nobleman of the Dębno family although the first written mention of Zolochiv was in 1423.

By 1523, it was already a city of Magdeburg rights.

Zolochiv was incorporated as a town on 15 September 1523 by the Polish king Sigismund I the Old. Located in the Ruthenian Voivodship of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, it belonged to several noble families.

From the first partition of Poland in 1772 until 1918, the town was part of the Austrian monarchy (Austria side after the compromise of 1867), head of the district with the same name, one of the 78 Bezirkshauptmannschaften in Austrian Galicia province, or "Crown land", in 1900.[3] The fate of this province was then disputed between Poland and Russia, until the Peace of Riga in 1921, attributing Galicia to the Second Polish Republic.

From 15 March 1923 until the Invasion of Poland in 1939, when the town was occupied by the Soviet Union, Zolochiv, still named Złoczów, belonged to the Tarnopol Voivodship of the second Polish Republic.

On 2 July 1941, at the outset of Operation Barbarossa, the town was occupied by Nazi Germany and then, from July 1944 to 16 August 1945, by the Red Army.

After the Yalta Conference (4–11 February 1945), drawn as a consequence of the findings of the interim Government of national unity signed on August 16, 1945, an agreement with the USSR, recognising the slightly modified Curzon line for the Eastern Polish border, on the basis of the agreement on the border between the Soviet Union and Polish Committee of National Liberation Government on 27 July 1944. In the Tarnopol voivodeship agreements, Zolochiv was included in the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic in the USSR, where it remained until 1991.

Since 1991, Zolochiv has been part of independent Ukraine.

World War Two

During the occupation by Nazi Germany (July 1941 – July 1944) Zolochiv was incorporated into the General Government in the District of Galicia.

On 27 June, the town and its surrounding vicinity was bombed by the Germans, people ran in many different directions and panicked. In the weeks prior the Germans had parachuted into the area.[4]

On 1 July the Germans arrived in the town, rumours had been circulating of a massacre in the Old Polish Prison, a two-three storied building on Ternopil St. Many Ukrainian locals were able to identify their friends and love ones amongst the victims. Several rows of corpses were lined up in a pit in the prison yard that was encrusted with blood and human flesh. People repeated that the NKVD had been running tractor engines during the massacre to quiet the noise of those being tortured.[5]

Those clearing the yard had to work quickly as due to the summer heat the bodies were decomposing and there was a risk of disease spreading. Inside the prison cells, Greek-Catholic priests were found with crosses carved into their chests. In one cell a pool of coagulated blood lay with numerous corpses that had been severely tortured.[6]

One of the local Jews, named Shmulko, who had worked in the flour mill before the war but had joined the NKVD and worked at the prison upon the Soviet invasion, was captured near Sasiv. The individual was forced to show people the corpses of their relatives and friends and was then stoned to death. Before he died he confessed to a second burial pit, that people had suspected but could not find. [7]

The Germans forced local Jews to clear the prison and clean the bodies of those killed and place them outside of the prison for further identification. After that SS troops executed those Jewish people, no Ukrainians participated.[7]

On 4 July 1941 for three days 3,000–4,000 Jews were murdered. The German soldiers were active in the murders

In November 1941, the Germans kidnapped nearly 200 Jewish youngsters to the work camp, Latski-Vielkia. On 30 August 1942, about 2,700 Jews were put inside cattle cars and sent to the Bełżec extermination camp.

There are numerous recorded cases of local Ukrainians sheltering Jews within the town of Zolochiv and the surrounding provinces. During the wartime the mayor of Zolochiv was Polish.[8]

In the Spring of 1942, the OUN ambushed a Nazi transportation of livestock to the Reich, killing one or more Nazis. There were immediate reprisals on local Ukrainian nationalists. The Gestapo was vigilant and focused on eliminating the OUN within and around Zolochiv. Numerous Ukrainian nationalists were imprisoned in the Gestapo headquarters in Zolochiv and were later transported to La ̨cki prison in Lviv, these included Ivan Lahola, Bohdan Kachur and Stepan Petelycky.[9]

On 1 December 1942 a ghetto was established, confined within the ghetto was a brewery where beer continued to be produced. The ghetto was guarded by Jewish police who were sometimes brutal and would beat those within the ghetto.[10] Between 7,500–9,000 people were imprisoned there, as well as remnants of communities of the surrounding areas, including Olesko, Sasov, and Biali Kamen. The ghetto was liquidated on 2 April 1943, 6,000 people were murdered in a mass execution perpetrated by an Einsatzgruppen at a pit near the village of Yelhovitsa.[11]

Architectural landmarks

- Zolochiv Castle, built in the early 17th century by Jakub Sobieski (the king's father)

- Stone Synagogue, 1724[12] (destroyed during World War II)

- Church of the Assumption, Zolochiv, 1730

- St. Nicolas Church, Zolochiv, 16th century

- Church of the Resurrection, Zolochiv, 17th century

- Church of the Ascension, Zolochiv, 19th century

- Arsenal, Zolochiv, 15th century

Notable people

- Tadeusz Brzeziński, Polish diplomat, father of Zbigniew Brzezinski

- Jan Cieński, Roman Catholic bishop

- Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Yiddish writer

- Franz von Hillenbrand, a German aristocrat, Imperial and Royal accountant

- Roald Hoffmann, chemist who won the 1981 Nobel Prize in Chemistry

- Andriy Husin, football player

- Naphtali Herz Imber, Jewish poet, wrote lyrics of Hatikvah, the national anthem of Israel

- Marian Iwańciów, painter

- Rabbi Yechiel Michel, Maggid (Preacher) of Zlotshev

- Ilya Schor, painter, jeweler, engraver, and artist of Judaica

- Abraham Shalit, Jewish historian

- James Sobieski, Polish prince

- John III Sobieski, king of Poland

- Katarzyna Sobieska, sister of John III Sobieski and a noble lady

- Igor Vovchanchyn, MMA fighter

- Weegee, photographer born Arthur Fellig

- Rabbi Zev Wolf

- Ignacy Zaborowski, mathematician, professor

- Carlos Felberbaum (1922–2018); Opera - Singer under the name of Carlos Feller; emigrated in 1929 with his family to Uruguay

Picture gallery

Zolochiv Castle

Zolochiv Castle Great Palace of Zolochiv Castle

Great Palace of Zolochiv Castle Church of the Assumption

Church of the Assumption Interior of the Assumption Church

Interior of the Assumption Church St. Nicholas Church

St. Nicholas Church Church of the Resurrection

Church of the Resurrection Monastery of the Order of Saint Basil the Great

Monastery of the Order of Saint Basil the Great Church of the Ascension

Church of the Ascension Old houses in the town center

Old houses in the town center Old houses in the town center

Old houses in the town center Old houses in the town center

Old houses in the town center Old houses in the town center

Old houses in the town center

References

- Чисельність наявного населення України на 1 січня 2018 року. Державна служба статистики України. Київ, 2018. стор.50

- "Чисельність наявного населення України (Actual population of Ukraine)" (in Ukrainian). State Statistics Service of Ukraine. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- Die postalischen Abstempelungen auf den österreichischen Postwertzeichen-Ausgaben 1867, 1883 und 1890, Wilhelm Klein, 1967

- Petelycky, Stefan (1999). Into Auschwitz for Ukraine (PDF). Kashtan Press.

- Petelycky, Stefan (1999). Into Auschwitz for Ukraine (PDF). Kashtan Press.

- Petelycky, Stefan (1999). Into Auschwitz for Ukraine (PDF). Kashtan Press.

- Petelycky, Stefan (1999). Into Auschwitz for Ukraine (PDF). Kashtan Press.

- Petelycky, Stefan (1999). Into Auschwitz for Ukraine (PDF). Kashtan Press.

- Petelycky, Stefan (1999). Into Auschwitz for Ukraine (PDF). Kashtan Press.

- Petelycky, Stefan (1999). Into Auschwitz for Ukraine (PDF). Kashtan Press.

- http://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/pinkas_poland/pol2_00217.html

- "Zolochiv (also Zloczow, Zolochev), Ukraine. Stone synagogue, built in the 17th century. Interior. Photo 1913". Boris Feldblyum Collection. Archived from the original on 15 October 2004.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zolochiv. |

- Official city webpage (in Ukrainian)

- History of Zolochiv and Zolochiv Region (in Ukrainian) (in Ukrainian)