Earth's energy budget

Earth's energy budget accounts for the balance between the energy that Earth receives from the Sun,[note 1] and the energy the Earth radiates back into outer space after having been distributed throughout the five components of Earth's climate system.[2] This system is made up of Earth's water, ice, atmosphere, rocky crust, and all living things.[3]

Quantifying changes in these amounts is required to accurately model the Earth's climate.[4]

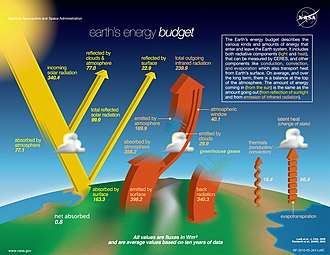

Received radiation is unevenly distributed over the planet, because the Sun heats equatorial regions more than polar regions. "The atmosphere and ocean work non-stop to even out solar heating imbalances through evaporation of surface water, convection, rainfall, winds, and ocean circulation."[5] Earth is very close to being in radiative equilibrium, the situation where the incoming solar energy is balanced by an equal flow of heat to space; under that condition, global temperatures will be relatively stable. Globally, over the course of the year, the Earth system—land surfaces, oceans, and atmosphere—absorbs and then radiates back to space an average of about 340 watts of solar power per square meter. Anything that increases or decreases the amount of incoming or outgoing energy will change global temperatures in response.[5]

However, Earth's energy balance and heat fluxes depend on many factors, such as atmospheric composition (mainly aerosols and greenhouse gases), the albedo (reflectivity) of surface properties, cloud cover and vegetation and land use patterns.

Changes in surface temperature due to Earth's energy budget do not occur instantaneously, due to the inertia of the oceans and the cryosphere. The net heat flux is buffered primarily by becoming part of the ocean's heat content, until a new equilibrium state is established between radiative forcings and the climate response.[6]

Energy budget

In spite of the enormous transfers of energy into and from the Earth, it maintains a relatively constant temperature because, as a whole, there is little net gain or loss: Earth emits via atmospheric and terrestrial radiation (shifted to longer electromagnetic wavelengths) to space about the same amount of energy as it receives via insolation (all forms of electromagnetic radiation).

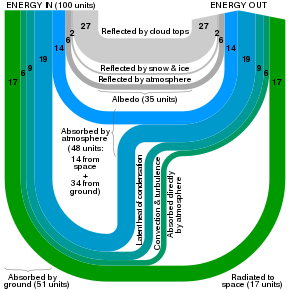

To quantify Earth's heat budget or heat balance, let the insolation received at the top of the atmosphere be 100 units (100 units = about 1,360 watts per square meter facing the sun), as shown in the accompanying illustration. Called the albedo of Earth, around 35 units are reflected back to space: 27 from the top of clouds, 2 from snow and ice-covered areas, and 6 by other parts of the atmosphere. The 65 remaining units are absorbed: 14 within the atmosphere and 51 by the Earth’s surface. These 51 units are radiated to space in the form of terrestrial radiation: 17 directly radiated to space and 34 absorbed by the atmosphere (19 through latent heat of condensation, 9 via convection and turbulence, and 6 directly absorbed). The 48 units absorbed by the atmosphere (34 units from terrestrial radiation and 14 from insolation) are finally radiated back to space. These 65 units (17 from the ground and 48 from the atmosphere) balance the 65 units absorbed from the sun in order to maintain zero net gain of energy by the Earth.[7]

Incoming radiant energy (shortwave)

The total amount of energy received per second at the top of Earth's atmosphere (TOA) is measured in watts and is given by the solar constant times the cross-sectional area of the Earth corresponded to the radiation . Because the surface area of a sphere is four times the cross-sectional area of a sphere (i.e. the area of a circle), the average TOA flux is one quarter of the solar constant and so is approximately 340 W/m².[1][8] Since the absorption varies with location as well as with diurnal, seasonal and annual variations, the numbers quoted are long-term averages, typically averaged from multiple satellite measurements.[1]

Of the ~340 W/m² of solar radiation received by the Earth, an average of ~77 W/m² is reflected back to space by clouds and the atmosphere and ~23 W/m² is reflected by the surface albedo, leaving ~240 W/m² of solar energy input to the Earth's energy budget. This gives the Earth a mean net albedo (specifically, its Bond albedo) of 0.306.[1]

Earth's internal heat and other small effects

The geothermal heat flux from the Earth's interior is estimated to be 47 terawatts[9] and split approximately equally between radiogenic heat and heat leftover from the Earth's formation. This comes to 0.087 watt/square metre, which represents only 0.027% of Earth's total energy budget at the surface, which is dominated by 173,000 terawatts of incoming solar radiation.[10]

Human production of energy is even lower, at an estimated 18 TW.

Photosynthesis has a larger effect: photosynthetic efficiency turns up to 2% of the sunlight striking plants into biomass. 100 to 140[11] TW (or around 0.08%) of the initial energy gets captured by photosynthesis, giving energy to plants.

Other minor sources of energy are usually ignored in these calculations, including accretion of interplanetary dust and solar wind, light from stars other than the Sun and the thermal radiation from space. Earlier, Joseph Fourier had claimed that deep space radiation was significant in a paper often cited as the first on the greenhouse effect.[12]

Longwave radiation

Longwave radiation is usually defined as outgoing infrared energy leaving the planet. However, the atmosphere absorbs parts initially, or cloud cover can reflect radiation. Generally, heat energy is transported between the planet's surface layers (land and ocean) to the atmosphere, transported via evapotranspiration and latent heat fluxes or conduction/convection processes.[1] Ultimately, energy is radiated in the form of longwave infrared radiation back into space.

Recent satellite observations indicate additional precipitation, which is sustained by increased energy leaving the surface through evaporation (the latent heat flux), offsetting increases in longwave flux to the surface.[4]

Earth's energy imbalance

If the incoming energy flux is not equal to the outgoing energy flux, net heat is added to or lost by the planet (if the incoming flux is larger or smaller than the outgoing respectively).

Indirect measurement

An imbalance in the Earth radiation budget requires components of the climate system to change temperature over time. The ocean is an effective absorber of solar energy and has a far greater heat capacity than the atmosphere. The measurement of the change in temperature is very difficult since it corresponds to millidegrees over the short time frame of the ARGO measurements. Ocean heat content change (OHC) over time is same measurement as the temperature anomaly over time.

Earth's energy balance may be measured by Argo floats by measuring the temperature anomaly or equivalently, the accumulation of ocean heat content. Ocean heat content was unchanged in the northern extra-tropical ocean and in the tropical ocean during the 2005-2014 time frame. Ocean heat content increased only in the extra-tropical southern ocean. There is no known reason that the extra-tropical southern ocean will experience ocean heat content increases while ocean heat content remains constant over the bulk of the measured ocean. The measurement urgently requires confirmation by both longer term measurements and by an alternate method. It is useful to note that the ocean heat content anomaly of the Argo float measurement is approximately 3x1022 joules, or approximately three days of excess solar insolation over the nine year period, or less than a ~0.1% variation of solar insolation over nine years. During the same period, CERES measured top of the atmosphere in and out-going radiation and found no trend. Since CERES precision is as good or better than the Argo floats, the discrepancy requires resolution concerning the trend, if any, in ocean heat content of the subtropical southern ocean.

Direct measurement

Several satellites directly measure the energy absorbed and radiated by Earth and by inference the energy imbalance. The NASA Earth Radiation Budget Experiment (ERBE) project involves three such satellites: the Earth Radiation Budget Satellite (ERBS), launched October 1984; NOAA-9, launched December 1984; and NOAA-10, launched September 1986.[13]

Today NASA's satellite instruments, provided by CERES, part of the NASA's Earth Observing System (EOS), are designed to measure both solar-reflected and Earth-emitted radiation.[14]

Natural greenhouse effect

.png)

The major atmospheric gases (oxygen and nitrogen) are transparent to incoming sunlight but are also transparent to outgoing thermal (infrared) radiation. However, water vapor, carbon dioxide, methane and other trace gases are opaque to many wavelengths of thermal radiation. The Earth's surface radiates the net equivalent of 17 percent of the incoming solar energy in the form of thermal infrared. However, the amount that directly escapes to space is only about 12 percent of incoming solar energy. The remaining fraction, 5 to 6 percent, is absorbed by the atmosphere by greenhouse gas molecules. [15]

When greenhouse gas molecules absorb thermal infrared energy, their temperature rises. Those gases then radiate an increased amount of thermal infrared energy in all directions. Heat radiated upward continues to encounter greenhouse gas molecules; those molecules also absorb the heat, and their temperature rises and the amount of heat they radiate increases. The atmosphere thins with altitude, and at roughly 5–6 kilometres, the concentration of greenhouse gases in the overlying atmosphere is so thin that heat can escape to space.[15]

Because greenhouse gas molecules radiate infrared energy in all directions, some of it spreads downward and ultimately returns to the Earth's surface, where it is absorbed. The Earth's surface temperature is thus higher than it would be if it were heated only by direct solar heating. This supplemental heating is the natural greenhouse effect.[15] It is as if the Earth is covered by a blanket that allows high frequency radiation (sunlight) to enter, but slows the rate at which the low frequency infrared radiant energy emitted by the Earth leaves.

Climate sensitivity

A change in the incident radiated portion of the energy budget is referred to as a radiative forcing.

Climate sensitivity is the steady state change in the equilibrium temperature as a result of changes in the energy budget.

Climate forcings and global warming

Climate forcings are changes that cause temperatures to rise or fall, disrupting the energy balance. Natural climate forcings include changes in the Sun's brightness, Milankovitch cycles (small variations in the shape of Earth's orbit and its axis of rotation that occur over thousands of years) and volcanic eruptions that inject light-reflecting particles as high as the stratosphere. Man-made forcings include particle pollution (aerosols) that absorb and reflect incoming sunlight; deforestation, which changes how the surface reflects and absorbs sunlight; and the rising concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases, which decreases the rate at which heat is radiated to space.

A forcing can trigger feedbacks that intensify (positive feedback) or weaken (negative feedback) the original forcing. For example, loss of ice at the poles, which makes them less reflective, causes greater absorption of energy and so increases the rate at which the ice melts, is an example of a positive feedback.[16]

The observed planetary energy imbalance during the recent solar minimum shows that solar forcing of climate, although natural and significant, is overwhelmed by anthropogenic climate forcing.[17]

In 2012, NASA scientists reported that to stop global warming atmospheric CO2 content would have to be reduced to 350 ppm or less, assuming all other climate forcings were fixed. The impact of anthropogenic aerosols has not been quantified, but individual aerosol types are thought to have substantial heating and cooling effects.[17]

See also

Notes

- Earth's internal heat and other small effects, that are indeed taken into consideration, are thousand times smaller; see § Earth's internal heat and other small effects

References

- "The NASA Earth's Energy Budget Poster". NASA. Archived from the original on 21 April 2014. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- IPCC AR5 WG1 Glossary 2013 "energy budget"

- IPCC AR5 WG1 Glossary 2013 "climate system"

- Stephens, Graeme L.; Li, Juilin; Wild, Martin; Clayson, Carol Anne; Loeb, Norman; Kato, Seiji; L'Ecuyer, Tristan; Stackhouse, Paul W. & Lebsock, Matthew (2012). "An update on Earth's energy balance in light of the latest global observations". Nature Geoscience. 5 (10): 691–696. Bibcode:2012NatGe...5..691S. doi:10.1038/ngeo1580. ISSN 1752-0894.

- "Climate and Earth's Energy Budget". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. 14 January 2009. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Previdi, M; et al. (2013). "Climate sensitivity in the Anthropocene". Royal Meteorological Society. 139 (674): 1121–1131. Bibcode:2013QJRMS.139.1121P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.434.854. doi:10.1002/qj.2165.

- Sharma, P.D. (2008). Environmental Biology & Toxicology (2nd ed.). Rastogi Publications. pp. 14–15. ISBN 9788171337422.

- Wild, Martin; Folini, Doris; Schär, Christoph; Loeb, Norman; Dutton, Ellsworth G.; König-Langlo, Gert (2013). "The global energy balance from a surface perspective" (PDF). Climate Dynamics. 40 (11–12): 3107–3134. Bibcode:2013ClDy...40.3107W. doi:10.1007/s00382-012-1569-8. ISSN 0930-7575.

- Davies, J. H.; Davies, D. R. (22 February 2010). "Earth's surface heat flux". Solid Earth. 1 (1): 5–24. doi:10.5194/se-1-5-2010. ISSN 1869-9529.Davies, J. H., & Davies, D. R. (2010). Earth's surface heat flux. Solid Earth, 1(1), 5–24.

- Archer, David (2012). Global Warming: Understanding the Forecast, 2nd Edition (2nd ed.). ISBN 978-0-470-94341-0.

- "Earth's energy flow - Energy Education". energyeducation.ca. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Fleming, James R. (1999). "Joseph Fourier, the 'greenhouse effect', and the quest for a universal theory of terrestrial temperatures". Endeavour. 23 (2): 72–75. doi:10.1016/S0160-9327(99)01210-7.

- "GISS ICP: Effect of the Sun's Energy on the Ocean and Atmosphere". icp.giss.nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Wielicki, Bruce A.; Harrison, Edwin F.; Cess, Robert D.; King, Michael D.; Randall, David A.; et al. (1995). <2125:mtpero>2.0.co;2 "Mission to Planet Earth: Role of Clouds and Radiation in Climate". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 76 (11): 2125–2153. Bibcode:1995BAMS...76.2125W. doi:10.1175/1520-0477(1995)076<2125:mtpero>2.0.co;2. ISSN 0003-0007.

- Lindsey, Rebecca (14 January 2009). "Climate and Earth's Energy Budget (Part 6-The Atmosphere's Energy Budget)". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. Earth Observatory, part of the EOS Project Science Office, located at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Lindsey, Rebecca (14 January 2009). "Climate and Earth's Energy Budget (Part 7-Climate Forcings and Global Warming)". earthobservatory.nasa.gov. Earth Observatory, part of the EOS Project Science Office, located at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- Hansen, James; Sato, Makiko; Kharecha, Pushker; von Schuckmann, Karina (January 2012). "Earth's Energy Imbalance". NASA.

Additional bibliography for cited sources

- IPCC AR5 Working Group I Report

- IPCC (2013). Stocker, T. F.; Qin, D.; Plattner, G.-K.; Tignor, M.; et al. (eds.). Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (PDF). Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-05799-9. (pb: 978-1-107-66182-0).

- IPCC (2013). "Annex III: Glossary" (PDF). IPCC AR5 WG1 2013. pp. 1447–1465.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Earth's energy budget. |