Louis Paulhan

Isidore Auguste Marie Louis Paulhan, known as Louis Paulhan (French: [pɔlɑ̃]; 19 July 1883 – 10 February 1963),[1] was a pioneering French aviator. He is known for winning the first Daily Mail aviation prize for the first flight between London and Manchester in 1910.

Biography

Paulhan was born at Pézenas, Hérault, and his heavier-than-air flying career began with making model aircraft. Stationed at St Cyr as a balloon pilot during his military service, in 1905 he won a competition for model aircraft design. Following his national service, he was employed by the balloon manufacturer Édouard Surcouf as an engineer, working on the construction of the dirigible La Ville de Paris and making many flights as its mechanic during 1907.[2] The same year he won a competition for model aircraft design in which the first prize was to be a full-size construction of the winning design.[3] His design was so complex that instead he was given a Voisin airframe. With the help of family and friends, he obtained an engine and taught himself to fly in 1909. He was issued with French pilot licence No.10. (The first batch of 10 licences was issued in alphabetical order of surname.)

He quickly established himself as gifted pilot. He took part in many airshows, including one in La Brayelle Airfield, Douai, in July 1909, where he set new records for altitude (150 metres (490 ft)) and duration (1h 07m), covering 47 kilometres (29 mi), and the Grande Semaine d'Aviation in Rheims where he crashed. In Lyon, flying a Farman III, he broke three records: height (920 m), speed (20 km in 19 minutes) and weight, carrying a 73-kilogram (161 lb) passenger. He flew at the Blackpool Aviation Week in October 1909, Britain's first air show.[4]

On 29 October 1909, Paulhan made the first official powered flight at Brooklands, Surrey, England, in his biplane made by Farman Aviation Works. This was also the first public flying display at Brooklands and some 20,000 spectators watched him fly to a height of 220 metres (720 ft). Local press reported that the land surrounded by the Brooklands Motor Racing Track was converted into an aerodrome for this event by a gang of men working day and night.

Touring America

In January 1910, Paulhan was invited to America to take part in airshows and competitions, at the Los Angeles International Air Meet.[5] He arrived with two Blériot monoplanes and two Farman biplanes. The Wright brothers, though not taking part in the event, were there with their lawyers to prevent Paulhan and Glenn Curtiss from flying. The Wrights claimed that the ailerons on their aircraft infringed patents. Paulhan flew anyway, winning all of the prizes and $19,000. He set up a new altitude record of 4,164 feet (1,269 m), beating his own previous record of 1,900 feet (580 m), and won the endurance prize with a flight lasting 1hr 49mn 40sec. He gave William Randolph Hearst his first experience of flight. However, he seems to have let down William Boeing, who had been enthused by the new invention of the aeroplane:

_Mrs._Dick_Ferris_at_the_Dominguez_Air_Meet%2C_Los_Angeles%2C_1910_(CHS-5592).jpg)

While attending the first American Air Meet in Los Angeles, Boeing asked nearly every aviator for a ride, but no one said yes except Paulhan. For three days Boeing waited, but on the fourth day he discovered Paulhan had already left the meet. Possibly, one of the biggest missed opportunities in Paulhan's life was the ride he never gave Boeing.[6]

From Los Angeles, Paulhan moved on to give exhibitions in Salt Lake City, Utah, where the Deseret News headline announced that the "Air King is Here to Fly".[7] He also appeared in New Orleans and made the first aeroplane flight in Texas.

The Wright brothers' case led, on 17 February, to a Federal judge ordering Paulhan to pay $25,000 for every paid display. Furious, he cancelled his American tour and went to New York City to challenge the Wright brothers by giving public demonstration flights for free. The dispute rumbled on and in March an agreement was reached whereby he could continue to give flying exhibitions in his Farman biplane on condition that he pay a $6,000 a week bond, pending the outcome of the case. The affair threatened the planned international aviation meet to be hosted by the Aero Club of America, at which the competition for the Gordon Bennett Trophy was to be held. According to Courtlandt Field Bishop, president of the Aero Club of America, all the leading foreign aviators had assured him that they would not appear in the country until the case was decided. If Paulhan won, they would compete; if he lost they did "not care to place themselves within the jurisdiction of American courts."[8] Paulhan eventually left quietly for France.

The Wrights' patent case dragged on for many more years, involving Curtiss and many other pilots and manufacturers.

Back in Europe

Returning to Europe, Paulhan continued his flying exploits. In April 1910, he won the London to Manchester air race, taking the £10,000 prize offered for flying from London to Manchester, a distance of 195 miles (314 km). This prize had been offered in 1906 by the Daily Mail for the first pilot to fly from London to Manchester within 24 hours. The flight had to start and finish within five miles of the Daily Mail office in each city, with no more than two landings en route. In 1906 this seemed an impossible feat – the best European fliers at that time could only stay aloft for seconds. Paulhan arrived in Manchester 12 hours after setting out from London, having spent 4 hours 12 minutes in the air, with an overnight stop at Lichfield, 117 miles from his starting point. He thus beat the British contender, Claude Grahame-White. There is a blue plaque on a house in Paulhan Road, Burnage, Manchester, at the site of his winning landing.[9]

In 1910 Paulhan was one of the first pilots to fly a seaplane, the Hydravion designed by Henri Fabre, and won a £10,000 prize for the most flights made in the year. He also turned his attention to aircraft design, producing the Paulhan biplane in association with Fabre, a large triplane which was flown at the 1911 French military aircraft trials competition, and the Aéro-Torpille in association with Victor Tatin.

In February 1912, he opened a seaplane flying school in Villefranche-sur-Mer before moving to Arcachon .

First World War

In the First World War, Paulhan was mobilised as a pilot with the rank of lieutenant on 15 September 1914, serving initially in northern France near to Amiens. He was transferred to the Serbian front in 1915,[10] where he was not only the most experienced but also the oldest aviator. In Serbia, he commanded a squadron of 10 Maurice Farman aeroplanes. In flight he was sometimes accompanied by a machine gunner or, it seems, by a mechanic carrying out repairs in flight.[11] The Serbian campaign was unsuccessful, but Paulhan is credited with the world's first "medevac" when he flew the seriously ill Milan Stefanik to safety. Decorated with the croix de guerre, he returned to France and flew no more missions, but returned to construction, notably of propellors, for the French military. After the war, he was made an Officer of the Légion d'honneur.[10]

After 1918

On demobilisation, Paulhan became a seaplane builder, building machines under licence from Curtiss. He worked at aircraft construction with engineer Pillard at the Société Provençale de Constructions Aéronautiques, building in 1928 the first all-metal seaplane in France, the SPCA Paulhan-Pillard T3.[12] He left the work the day when his only son, René, died on 10 May 1937, at the presentation of a fighter plane. He contributed to the manufacture of Dewoitine planes, but retired to Saint-Jean-de-Luz, which he rarely left before his death. In 1960, Paulhan was invited by Air France to be one of the passengers on its inaugural non-stop flight from Paris to Los Angeles.

In 1927, Paulhan was a co-founder of the company Société Continentale Parker in France together with Robert Deté, Enea Bossi and Pierre Prier. The purpose was to transfer surface treatment technologies for the growing aerospace industry to Europe. They started with a licence from Parker Rust-Proof of Detroit (Parkerizing or phosphating) and in a later step with the distribution rights of Udylite Corp for specialty chemicals in electroplating. The company's successor organizations, Chemetall GmbH and Coventya GmbH, later became the European market leaders in surface treatment.

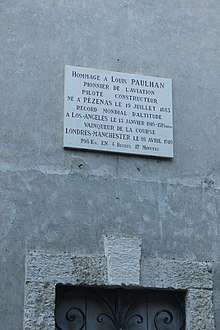

Paulhan died on 10 February 1963 at Saint-Jean-de-Luz. He is buried in his home town of Pézenas where a monument has been erected in commemoration; a wall plaque in Rue Conti in Pézenas also recalls his achievements.

See also

Notes and references

- Hérault département archives: Pézenas : registres de l'année 1880 - 1884 Archived 26 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "Banquet de Aéronautique-Club de France en l'Honneur de Louis Paulhan". l'Aérophile (in French): 562. 15 December 1909.

- "Concours de modèles d'Aéroplanes". l'Aérophile (in French): 171. June 1907.

- "Blackpool Aviation Week Report". Flight magazine. 30 October 1909.

- "LOS ANGELES AVIATION MEET TO BE EMULATED BY OTHER WESTERN CITIES". The Washington Post. 23 January 1910.

- "William Boeing". National Aviation Hall of Fame. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- "Air King Is Here To Fly". Deseret News. 21 January 1910. Archived from the original on 25 May 2011. Retrieved 28 September 2006.

- "If Wright Brothers Win, America will Lose International Aviation Meet". Daily Journal and Tribune. 13 March 1910. Archived from the original on 18 October 2006. Retrieved 28 September 2006.

- Chris Paul: Labour of Love: Burnage, Manchester: Claims to Fame

- L'homme-vent, special issue of L'Ami de Pézenas, 2010, ISSN 1240-0084.

- "Louis Paulhan, l'homme vent" (PDF). Collège Louis Paulhan à Sartrouville. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2003. Retrieved 28 September 2006.

- "La SPCA". Archived from the original on 26 June 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Louis Paulhan. |

- Henri Farman, "En suivant Paulhan", La vie au grand air 7 May 1910. A detailed contemporary account of the London-Manchester air race, with several photos (in French)

- The First U.S. Airshows--the Air Meets of 1910

- Film of Paulhan being congratulated after setting endurance records at Dominguez Field on YouTube

- Paulhan in Salt Lake City

- Les hydro aéroplanes Paulhan-Curtiss Biography, hydroplane development, photos(in French)