1910 London to Manchester air race

The 1910 London to Manchester air race took place between two aviators, each of whom attempted to win a heavier-than-air powered flight challenge between London and Manchester first proposed by the Daily Mail newspaper in 1906. The £10,000 prize was won in April 1910 by Frenchman Louis Paulhan.

The first to make the attempt was Claude Grahame-White, an Englishman from Hampshire. He took off from London on 23 April 1910, and made his first planned stop at Rugby. His biplane subsequently suffered engine problems, forcing him to land again, near Lichfield. High winds made it impossible for Grahame-White to continue his journey, and his aeroplane suffered further damage on the ground when it was blown over.

While Grahame-White's aeroplane was being repaired in London, Paulhan took off late on 27 April, heading for Lichfield. A few hours later Grahame-White was made aware of Paulhan's departure, and immediately set off in pursuit. The next morning, after an unprecedented night-time take-off, he almost caught up with Paulhan, but his aeroplane was overweight and he was forced to concede defeat. Paulhan reached Manchester early on 28 April, winning the challenge. Both aviators celebrated his victory at a special luncheon held at the Savoy Hotel in London.

The event marked the first long-distance aeroplane race in England, the first take-off of a heavier-than-air machine at night, and the first powered flight into Manchester from outside the city. Paulhan repeated the journey in April 1950, the fortieth anniversary of the original flight, this time as a passenger aboard a British jet fighter.

History

On 17 November 1906 the Daily Mail newspaper offered a £10,000 prize for the first aviator to fly the 185 miles (298 km) between London and Manchester, with no more than two stops, in under 24 hours.[1] The challenge also specified that take-off and landing were to be at locations no more than five miles from the newspaper's offices in those cities.[2] Powered flight was a relatively new invention, and the newspaper's proprietors were keen to stimulate the industry's growth; in 1908 they offered £1,000 for the first flight across the English channel (won on 25 July 1909 by the French aviator Louis Blériot), and £1,000 for the first circular one-mile flight made by a British aviator in a British aeroplane (won on 30 October 1909 by the English aviator John Moore-Brabazon).[1] In 1910, two men accepted the newspaper's 1906 challenge; an Englishman, Claude Grahame-White, and a Frenchman, Louis Paulhan.[2]

Claude Grahame-White was born in 1879 in Hampshire, England. He was educated at Crondall House School in Farnham, and later at Bedford Grammar School between 1892 and 1896.[3] Apprenticed to a local engineering firm, he later worked for his uncle Francis Willey, 1st Baron Barnby. He started his own motor vehicle business in Bradford, before travelling to South Africa to hunt big game. In 1909, inspired by Blériot's historic cross-channel flight, he went to France to learn how to fly, and by the following January he became one of the first Englishmen to obtain an aviator's certificate. He also started a flying school at Pau, which he moved to England later that year.[4][5]

Isidore Auguste Marie Louis Paulhan, better known as Louis Paulhan,[6] was born in 1883 in Pézenas, in the south of France. After doing military service at the balloon school at Chalais-Meudon he had worked as an assistant for Ferdinand Ferber before winning a Voisin biplane in an aircraft design competition. Paulhan taught himself to fly using this aircraft, and was awarded Aéro Club de France licence No. 10 on 17 July.[7] Paulhan was no stranger to British audiences; he competed in an early flight meeting in October 1909 at Blackpool, and shortly afterwards flew in an exhibition at the Brooklands motor racing circuit.[6] Paulhan took part in many airshows, including several in the United States of America, and in Douai, where in July 1909 he set new records for altitude and flight duration.[8][9]

Grahame-White's first attempt

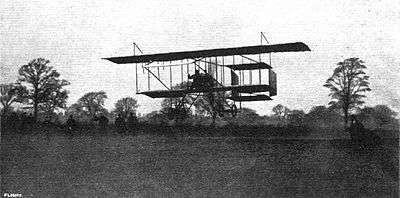

Grahame-White was the first to attempt the journey. He planned to take off at 5:00 am on 23 April 1910, near the Plumes Hotel in the London suburb of Park Royal. A crowd of journalists and interested spectators assembled there from about 4:00 am, with more arriving by car, until about 200–300 were present. The Times described the sky as "clear and starlit", and the weather as "very cold, as there was a slight frost." Grahame-White arrived at about 4:30 am and began to prepare his Farman III biplane. The aeroplane was brought into the field from the yard it was stored in, and its seven-cylinder 50 hp rotary engine was started. Once the engine warmed up, Grahame-White took his seat. Several people wished him well, including his sister, mother and Henry Farman. He guided the biplane for about 30–60 yards across the frosted grass, and took off at about 5:12 am,[nb 1] before altering his direction to head for the start of the course—a gasometer at Wormwood Scrubs, within the required five-mile radius of the Daily Mail office in London.[2][10][11]

Cheered loudly by the thousands of spectators who anticipated his arrival, Grahame-White flew across the starting point and turned north-west toward Wembley. Standing on top of the gasometer, Harold Perrin, secretary of the Royal Aero Club, waved a flag to indicate the start of Grahame-White's attempt. By 5:35 am the aviator was over Watford, and at 6:15 am he flew over Leighton Buzzard. Crowds of cheering spectators were there to greet him as he flew above the line of the London and North Western Railway, at an altitude of about 400 feet (120 m). Meanwhile, Perrin and two mechanics from Gnome et Rhône (who supplied the engine used on the Farman III) boarded one of two cars, and were headed for Rugby. Along the way, one car took a short cut across a field and crashed into a ridge; one occupant was seriously injured.[10][11]

The Times (1910), reporting on Grahame-White's condition upon landing at Rugby.[11]

Grahame-White made his first stop in Rugby just after 7:15 am. One of the cars that left London arrived about 10 minutes before he landed, and his mechanics attended to his aeroplane. News of his take-off in London reached the area, and a large crowd gathered; they were kept from the aeroplane by a group of boy scouts. Grahame-White was taken to nearby Gellings Farm, where he drank coffee and ate biscuits, and told those present about his journey.[10] "It was wretchedly cold all the way ... and I was cold at the start. My eyes suffered towards the end, and my fingers were quite numbed." Grahame-White's average speed was estimated at more than 40 miles per hour (64 km/h); a few of the vehicles following him from London did not arrive until some time after his descent.[11]

He took off again at about 8:25 am, but was unable to reach his next scheduled stop at Crewe. About 30 miles outside Rugby a problem with the engine's inlet valves forced him to land in a field at Hademore, four miles outside of Lichfield—about 115 miles into the 185-mile journey. On landing, he damaged a skid, and his mechanics were telegraphed for. While the necessary repairs were being made, Grahame-White ate lunch and then slept for a few hours, looked after by his mother, who had arrived by car. Meanwhile, a large crowd of interested spectators gathered, and the farmer who owned the field charged them for admission. Soldiers from a nearby barracks kept the public from getting too close to the biplane.[11]

As the sun fell the wind grew in strength, and at 7:00 pm Grahame-White conceded that the high winds made any further progress impossible. He decided to try again at 3:00 am, hoping to reach Manchester by the 5:15 am deadline, but at 3:30 am he abandoned the attempt, and said that he would travel to Manchester and try again from there. He ordered the soldiers to peg the aeroplane down, but his instructions were ignored; the next night it was blown over by strong winds and severely damaged.[11][12]

Paulhan's attempt

Grahame-White's biplane was returned to London, and on 25 April was being repaired at Wormwood Scrubs, in the Daily Mail's hangar. Paulhan arrived at Dover from California, where he performed exhibition flights.[13] Another competitor, Emile Dubonnet, also formally entered the contest, and was due to try a few days later. On 27 April 1910 Paulhan's biplane (a newer model than Grahame-White's) was brought to Hendon, on the site of what is now the London branch of the Royal Air Force Museum.[14] It was assembled in less than 11 hours, and at 5:21 pm that day Paulhan took off for Hampstead Cemetery, his official starting line. He arrived there ten minutes later, flew on to Harrow, and began to follow the route of the London and North Western Railway. The railway company prepared for the event by whitewashing the sleepers of the correct line for the competitors to follow.[15] Paulhan was followed by a special train, on board which were Mme. Paulhan and Henry Farman. Other members of his party followed by car.[12]

Grahame-White attempted to make a test flight earlier that day, but the huge crowds hampered his efforts, and he was unable to take off. Having spent two days supervising the reconstruction of his aeroplane, he retired to a nearby hotel. At about 6:10 pm he was awakened with the news that Paulhan had begun his attempt, and he decided to set off in pursuit. This time he had no trouble clearing a space in the crowd.[15] His biplane's engine was started, and by 6:29 pm he passed the starting line. Almost an hour later he flew over Leighton Buzzard, just as Paulhan was passing over Rugby. As night approached, Grahame-White landed his aeroplane in a field near the railway line at Roade, in Northamptonshire.[16][17] Fifteen minutes later, Paulhan reached Lichfield, where about 117 miles (188 km) into his journey he ran out of fuel. He managed to land the biplane in a field near Trent Valley railway station.[12][18] The aeroplane was pegged down, and Paulhan left with his colleagues to stay overnight at a nearby hotel. Grahame-White meanwhile stayed at the house of a Dr. Ryan. Both aviators intended to restart at 3:00 am the following day.[17]

Louis Paulhan[19]

Still about 60 miles (100 km) behind the Frenchman, Grahame-White made a historic decision; he would make an unprecedented night flight.[20] Guided by the headlamps of his party's cars, he took off at 2:50 am. Within minutes of becoming airborne however, he almost crashed; while he was leaning forward to make himself comfortable, his jacket brushed the engine ignition switch and he accidentally turned the engine off, but he quickly corrected his error and was able to continue.[15] Using the lights of railway stations to guide his course through the pitch black night, within 40 minutes he reached Rugby, and at 3:50 am he passed Nuneaton. Despite making good progress, Grahame-White was carrying a large load of fuel and oil, and his engine was not powerful enough to raise the aeroplane over the high ground before him. Disappointed, he landed at Polesworth, about 107 miles (172 km) from London, and only 10 miles behind Paulhan.[15] A few minutes later the Frenchman, unaware of Grahame-White's progress, resumed his journey. He passed Stafford at 4:45 am, Crewe at 5:20 am, and at 5:32 am he landed at Barcicroft Fields near Didsbury, within five miles of the Manchester office of the Daily Mail, thereby winning the contest. His party was taken by train to a civic reception, held by the Lord Mayor of Manchester.[21] Grahame-White was notified of Paulhan's success, and reportedly shouted "Ladies and gentlemen, the £10,000 prize has been won by Louis Paulhan, the finest aviator that the world has ever seen. Compared with him I am only a novice. Three cheers for Paulhan!"[22] He retired to bed, leaving his mechanics to repair his aeroplane, and later sent Paulhan a telegram, congratulating his rival on his achievement. Grahame-White attempted to resume his journey to Manchester, and reached Tamworth, but he later abandoned the flight.[16][17][22]

Presentation

Paulhan was presented with his prize—a golden casket containing a cheque for £10,000—on 30 April 1910, during a luncheon at the Savoy Hotel in London. The event was presided over by the editor of the Daily Mail, Thomas Marlowe (in lieu of Lord Northcliffe) and attended by, among others, French ambassador Paul Cambon. Grahame-White was given a consolation prize of an inscribed white-silver bowl, filled with red and white roses.[23][24]

I am in England for the second time, and I must say in no country that I have visited have I ever received a more cordial welcome. I believe sincerely that the victory I have won belongs of right to your brilliant and courageous compatriot Mr. Grahame-White. [Cheers.] I am proud to have had him as my rival in this battle of the air. In the name of the aviators both of France and of all the other countries I offer my congratulations to the great English journal, the Daily Mail, which, by its magnificent prizes, has given an inestimable stimulus to the science of aviation, and has thus contributed more than any other agency to the conquest of the air.

Legacy

The events of 27–28 April constituted the world's first long-distance air race, and also marked the first night-time take-off of a heavier-than-air machine; Grahame-White's decision proved that night-time take-off, flight and navigation were possible, provided that the pilot was able to relate his position to the ground. Grahame-White did this with the help of friends, one of whom shone his car's headlamps onto the wall of a public house.[25] Paulhan's arrival in Didsbury was notable for being the first powered flight into Manchester from any point outside the city. His achievement is commemorated by a blue plaque, fixed to the front wall of 25–27 Paulhan Road, a pair of 1930s semi-detached houses near the site of his landing.[21]

Within weeks of Paulhan's victory, the Daily Mail offered a new prize; £10,000 to the first aviator to cover a 1,000-mile (1,609-km) circuit of Britain in a single day, with 11 compulsory stops at fixed intervals. The challenge was completed by M Beaumont on 26 July 1911, in about 22½ hours. Paulhan and Grahame-White competed again later in 1910, for the newspaper's prize of £1,000 for the greatest aggregate cross-country flight, which Paulhan won.[1]

The flight's 25th anniversary was celebrated at the Aero Club of France, in Paris, on 16 January 1936. Present at the banquet were Paulhan and Grahame-White, along with the French Air Minister Victor Denain, Prince George Valentin Bibescu (President of the FAI), Harold Perrin, and a number of other notable dignitaries as well as early aviators and constructors such as Farman, Voisin, Breguet, Caudron, Bleriot and Anzani.[26]

Although by then retired from flying, on 28 April 1950—the fortieth anniversary of the 1910 flight—Paulhan repeated the journey from London to Manchester, this time as a passenger on board a Gloster Meteor T7, the two-seater training variant of the first British jet fighter. After travelling at 400 mph (644 km/h), the 67-year-old Frenchman said "C'était magnifique ... It was all I ever dreamed of in aviation—no propellers, no vibration." The Daily Mail entertained him at the Royal Aero Club in London, where he was accompanied by his former rival, Claude Grahame-White.[27]

References

Footnotes

- Flight magazine estimated the time as 5:15 am.[10]

- Flight notes he spoke in French

Notes

- The New Daily Mail Prizes, Flight, hosted at flightglobal.com, 5 April 1913, p. 393, retrieved 20 May 2010

- Claxton 2007, pp. 72–73

- Obituary, The Old Bedfordian, No.9, April 1960, p.34

- Grimsditch, H. B. (May 2008) [2004], "White, Claude Grahame- (1879–1959), rev. Robin Higham", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, hosted at oxforddnb.com, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33512, retrieved 19 May 2010(subscription or UK public library membership required)

- Claude Grahame-White, Flight, hosted at flightglobal.com, 28 August 1958, p. 64, retrieved 19 January 2013

- M. Louis Paulhan, The Times, hosted at infotrac.galegroup.com, 12 February 1963, p.13, col. A (subscription required)

- Villard, Henry Serrano (1987), The Blue Riband of the Air, Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 33–4, ISBN 0-87474-942-5

- Pauley & Museum 2009, p. 56

- Vivre Dans Les Yvelines (in French), leparisien.fr, 30 January 2003, retrieved 22 May 2010

- "The London-Manchester £10,000 flight prize", Flight, Flight, hosted at flightglobal.com: 326, 30 April 1910, retrieved 19 May 2010

- Flight by Aeroplane, The Times hosted at infotrac.galegroup.com, 25 April 1910, p. 9, col. A (subscription required)

- "The London-Manchester £10,000 flight prize", Flight, hosted at flightglobal.com, II (70): 327, 30 April 1910, retrieved 19 May 2010

- Grahame-White, Claude (20 April 1950), In the Air (PDF), Flight, hosted at flightglobal.com, p. 495, retrieved 19 May 2010

- Harper, Harry (20 April 1950), London to Manchester 1910 (PDF), Flight, hosted at flightglobal.com, p. 493, retrieved 19 May 2010

- London to Manchester. £10,000 More for Prizes (PDF), Flight, hosted at flightglobal.com, 7 May 1910, p. 351, retrieved 19 May 2010

- Claxton 2007, p. 73

- The London-Manchester £10,000 flight prize, Flight, hosted at flightglobal.com, 30 April 1910, p. 328, retrieved 19 May 2010

- Brady 2001, pp. 84–85

- Aviators Tell of Great Race, The New York Times, written for The London Daily Mail, hosted at query.nytimes.com, 28 April 1910

- Brady 2001, p. 85

- Scholefield 2004, p. 211

- Loser Acclaims Victor (PDF), The New York Times, hosted at query.nytimes.com, 29 April 1910, p. 3

- "London to Manchester. £10,000 More for Prizes", Flight, flightglobal.com, II (71): 350, 7 May 1910, retrieved 19 May 2010

- The Aeroplane Race, The Times, hosted at infotrac.galegroup.com, 2 May 1910, p. 10, col. A (subscription required)

- Brady 2001, p. 86

- A Flight that Lives (PDF), Flight, hosted at flightglobal.com, 23 January 1936, p. 90, retrieved 19 May 2010

- 1910 Prizewinner Flies Again, The Times, hosted at infotrac.galegroup.com, 28 April 1950, p. 3, col. A (subscription required)

Bibliography

- Brady, Tim (2001), The American Aviation Experience: A History, Illinois, US: Southern Illinois University Press, ISBN 0-8093-2371-0

- Claxton, William J. (2007), The Mastery of the Air, Middlesex, UK: Echo Library, ISBN 978-1-4068-4626-3

- Pauley, Kenneth E.; Museum, Dominguez Rancho Adobe (2009), The 1910 Los Angeles International Aviation Meet, US: Arcadia Publishing, ISBN 978-0-7385-7190-4

- Scholefield, R.A. (2004), Manchester's Early Airfields, an extended article in Moving Manchester, Stockport, UK: Lancashire & Cheshire Antiquarian Society, ISSN 0950-4699