Daily Office (Anglican)

Since the English Reformation, the Daily Office in Anglican churches has principally been the two daily services of Morning Prayer (sometimes called Mattins or Matins) and Evening Prayer (usually called Evensong, especially when celebrated chorally). These services are generally celebrated according to set forms contained in the various local editions of the Book of Common Prayer. The Daily Offices may be led either by clergy or lay people. In many Anglican provinces, clergy are required to pray the two main services daily.

| Part of a series on |

| Anglicanism |

|---|

|

|

Ministry and worship |

|

|

|

Background and history |

|

|

History

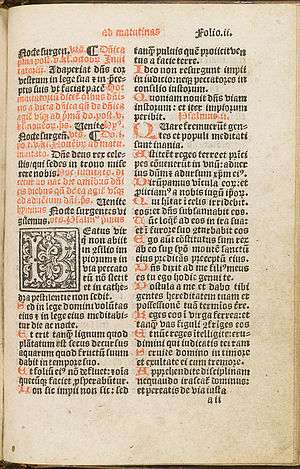

The Anglican practice of saying daily morning and evening prayer derives from the pre-Reformation canonical hours, of which seven were required to be said in churches and by clergy daily: Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers, and Compline. This practice derived from the earliest centuries of Christianity, and ultimately from the pre-Christian hours of prayer observed in the Jewish temple.[1]

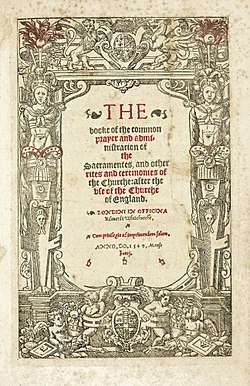

The first Book of Common Prayer of 1549[2] radically simplified this arrangement, combining the first three services of the day into a single service called Mattins and the latter two into a single service called Evensong (which, before the Reformation, was the English name for Vespers[3]). The rest were abolished. The second edition of the Book of Common Prayer (1552)[4] renamed these services to Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer, respectively, and also made some minor alterations, setting the pattern of daily Anglican worship which has been essentially unchanged in most cathedrals and other large churches ever since, continuing to the current edition of the Church of England's Book of Common Prayer of 1662.

In most Anglican provinces, ordained ministers are required to say Morning and Evening Prayer daily; devout lay Anglicans also often make this a part of their spiritual practice. Historically, Anglican religious communities have made the Daily Office a central part of their communal spiritual life, beginning with the community at Little Gidding established in the 17th century by Nicholas Ferrar.[5] Regular use of Morning and Evening Prayer from the Book of Common Prayer was also a part of the "method" promoted by John Wesley and the early Methodist movement.[6]:283

Since the Oxford (Tractarian) and ritualist movements of the 19th century, interest in the pre-Reformation practice of praying the office eight times a day has revived. Before his conversion to Roman Catholicism, the Tractarian priest John Henry Newman wrote in Tracts for the Times number 75 of the Roman Breviary's relation to the Church of England's daily prayer practices, encouraging its adoption by Anglican priests.[7] The praying of "little hours", especially Compline but also a mid-day prayer office sometimes called Diurnum, in addition to the major services of Morning and Evening Prayer, has become particularly common, and is provided for by the current service books of the Episcopal Church in the United States[8]:103–7, 127–36 and the Church of England.[9]:29–73, 298–323

The Anglican forms of the Daily Office have spread to other Christian traditions: as mentioned, the Anglican Morning and Evening Prayer services were a central part of the original Methodist practice. The popularity of choral Evensong has led to its adoption by some other churches around the world. In addition, since the Roman Catholic Church established the Pastoral Provision and the Anglican Use in the United States, and continuing into the current personal ordinariates for former Anglicans who have joined the Roman Catholic church, forms of Morning and Evening Prayer based on the Anglican pattern have come into use among some Roman Catholics, contained in the Book of Divine Worship and its successor publications.

Liturgical practice

Traditional Anglican worship of the Daily Office follows the patterns first set down in 1549 and 1552. Since the 20th-century liturgical movement, however, some Anglican churches have introduced new forms which are not based on this historic practice.[9][10] This section will describe the traditional form, which is still widely used throughout the Anglican Communion.

The Book of Common Prayer has been described as "the Bible re-arranged for public worship":[11]:155 the core of the Anglican Daily Office services is almost entirely based on praying using the words of the Christian Bible itself, and hearing readings from it.

Confession and absolution

According to the traditional editions of the Book of Common Prayer since 1552, both Morning and Evening Prayer open with a lengthy prayer of confession and absolution, but many Anglican provinces including the Church of England and the American Episcopal Church now no longer require this even at services according to the traditional forms.[12]:80[8]:37, 61, 80, 115

Opening responses

The traditional forms open with opening responses said between the officiating minister and the people, which are usually the same at every service throughout the year, taken from the pre-Reformation use: "O Lord, open thou our lips; and our mouth shall show forth thy praise", based on Psalm 51 and translated from the prayer which opens Matins in the Roman Breviary. Then follows "O God, make speed to save us" with the response "O Lord, make haste to help us", a loose translation of the Deus, in adjutorium meum intende which begins every service in the pre-Reformation hours, followed by the Gloria Patri in English.

Psalms and canticles

A major aspect of the Daily Office before the Reformation was the saying or singing of the Psalms, and this was maintained in the reformed offices of Morning and Evening Prayer. Whereas for hundreds of years the church recited the entire psalter on a weekly basis (see the article on Latin psalters), the traditional Book of Common Prayer foresees the whole psalter said over the longer time period of one month; more recently, some Anglican churches have adopted even longer cycles of seven weeks[8]:934 or two months.[13]:lv

At Morning Prayer, the first psalm said every day is Venite, exultemus Domino, Psalm 95, either in its entirety or with a shortened or altered ending. During Easter, the Easter Anthems typically replace it; other recent prayer books, following the example of the Roman Catholic Liturgy of the Hours as revised following the Vatican II council,[14] allow other psalms such as Psalm 100 to be used instead of the classical Venite.[8]:45, 82–3 After the Venite or its equivalent is completed, the rest of the psalms follow, but in some churches an office hymn is sung first.[15]:191–2

After each of the lessons from the Bible, a canticle or hymn is sung. At Morning Prayer, these are usually the hymn Te Deum laudamus, which was sung at the end of Matins on feast days before the Reformation, and the canticle Benedictus from the Gospel of Luke, which was sung every day at Lauds. As alternatives, the Benedicite from the Greek version of the Book of Daniel is provided instead of Te Deum, and Psalm 100 (under the title of its Latin incipit Jubilate Deo) instead of Benedictus. The combination of Te Deum and Jubilate has proven particularly popular for church music composers, having been set twice by Handel, as well as by Herbert Howells and Henry Purcell.

At Evening Prayer, two other canticles from the Gospel of Luke are usually used: Magnificat and Nunc dimittis, coming respectively from the services of Vespers and Compline. Psalms 98 and 67 are appointed as alternatives, but they are rarely used in comparison to the alternatives provided for Morning Prayer.

Bible readings

The introduction to the first Book of Common Prayer explained that the purpose of the reformed office was to restore what it described as the practice of the Early Church of reading the whole Bible through once per year, a practice it praised as 'godly and decent' and criticized what it perceived as the corruption of this practice by the mediaeval breviaries in which only a small portion of the scripture was read each year, wherein most books of the Bible were only read in their first few chapters, and the rest omitted.[8]:866–7

While scholars now dispute that this was the practice or intention of the Early Church in praying their hours of prayer,[16] the reading of the Bible remains an important part of the Anglican daily prayer practice. Typically, at each of the services of morning and evening prayer, two readings are made: one from the Old Testament or from the Apocrypha, and one from the New Testament. These are taken from one of a number of lectionaries depending on the Anglican province and prayer book in question, providing a structured plan for reading the Bible through each year.

Preces and collects

Usually the Apostles' Creed is said congregationally following the readings and canticles, then Kyrie eleison. The Lord's Prayer is said or sung and then the preces[Note 1] (also called suffrages) are said in a responsive pattern similar to that which opens the service. The versicles and responses follow an ancient pattern,[17]:120 including prayers for the civil authorities, for the ministers of the church and all its people, for peace, and for purity of heart.

Then the minister prays several collects. The first is usually a collect of the day, appropriate to the church season. According to the Church of England's prayer books and those modelled on it, there then follow two collects: at Morning Prayer, they are taken from the pre-Reformation orders for Lauds and Prime, respectively; and at Evening Prayer from Vespers and Compline.[18]:396–7, 403

Anthem

The rubric of the Book of Common Prayer of 1662 then reads 'In Quires and Places where they sing here followeth the Anthem.' At choral services of Mattins and Evensong, the choir at this point sings a different piece of religious music, which is freely chosen by the minister and choir. This usage is based on the practice of singing a Marian antiphon after Compline,[18]:397 and was encouraged after the Reformation by the directions of Queen Elizabeth I's 1559 directions that 'for the comforting of such that delight in music, it may be permitted, that in the beginning, or in the end of common prayers, either at morning or evening, there may be sung an hymn, or suchlike song to the praise of Almighty God'.[19]

Closing

In the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, five additional prayers were added to close the service.[18]:397 These were, in order, for the monarch, for the royal household, for the clergy and people, a concluding prayer taken from the Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom, and a benediction based on 2 Corinthians 13:14 often referred to by Anglicans simply as 'the grace'.

In modern practice, the anthem is usually followed by some prayers of intercession, or sometimes a sermon, before the congregation is dismissed[20]:22–3 Nonetheless the use of some of the five prayers, especially the grace and the Prayer of St Chrysostom, remains common.

Music

Since the services of Morning and Evening Prayer were introduced in the 16th century, their constituent parts have been set to music for choirs to sing. A rich musical tradition spanning these centuries has developed, with the canticles not only having been set by church music composers such as Herbert Howells and Charles Villiers Stanford, but also by well-known composers of classical music such as Henry Purcell, Felix Mendelssohn, Edward Elgar, and Arvo Pärt. Evening Prayer sung by a choir (usually called 'choral Evensong') is particularly common. In such choral services, all of the service from the opening responses to the anthem, except the lessons from the Bible, is usually sung or chanted.

Settings of the opening responses and the section from the Kyrie and Lord's Prayer up to the end of the collects are suitable for both Morning and Evening Prayer and are usually known by the title 'Preces and Responses'; settings of the canticles differ between the two services and, especially in the latter case, are usually called a "service" (i.e. 'Morning Service' and 'Evening Service'). Almost every Anglican composer of note has composed a setting of one or both components of the choral service at some point in their career. In addition, the freedom of choirs (and thus composers) to select music freely for the anthem after the collect has encouraged the composition of a large number of general religious choral works intended to be sung in this context.

The sung Anglican Daily Office has also generated its own tradition in psalm-singing called Anglican chant, where a simple harmonized melody is used, adapting the number of syllables in the psalm text to fit a fixed number of notes, in a manner similar to a kind of harmonized plainsong. Similarly to settings of the responses and canticles, many Anglican composers have written melodies for Anglican chant.

The psalms and canticles may also be sung as plainsong. This is especially common during Lent and at other penitential times.

See also

Notes

- In modern use the term 'preces' is often used to refer to the opening responses, and 'responses' the part of the service after the creed, due to a misunderstanding of the name Preces and Responses, a common title for choral settings of both of these parts of the service. The historical usage of the term in liturgics, however, is to refer to the part of the service nearer the end. "preces". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. March 2007. Retrieved 15 June 2019. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

References

- Lowther Clarke, W. K. (1922). Evensong Explained, with Notes on Matins and the Litany. London: SPCK. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- The Booke of the common praier and administracion of the Sacramentes, and other rites and ceremonies of the Churche: after the use of the Churche of Englande. London: Richard Grafton. 1549.

- "evensong". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. March 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2019. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- The Boke of common prayer, and administracion of the Sacramentes, and other rites and Ceremonies in the Churche of Englande. London: Edward Whitchurch. 1552.

- "Little Gidding community". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68969. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Kirby, James E.; Abraham, William J., eds. (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Methodist Studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199696116.

- "Newman Reader - Tracts for the Times - Tract 75". www.newmanreader.org. Retrieved 2019-06-10.

- The Book of Common Prayer … according to the use of The Episcopal Church. New York: Church Publishing Incorporated. 1979.

- Common Worship: Daily Prayer (Preliminary Edition). London: Church House Publishing. 2002. ISBN 0715120638.

- A New Zealand Prayer Book/He Karakia Mihinare o Aotearoa. Collins. 1989. ISBN 9780005990698.

- Dailey, Prudence, ed. (2011). The Book of Common Prayer: Past, Present, and Future. London: Continuum.

- Common Worship: Services and Prayers for the Church of England. London: Church House Publishing. 2000. ISBN 071512000X.

- The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church According to the Use of the Anglican Church of Canada. Toronto: Anglican Book Centre. 1962.

- Liber hymnarius cum invitatoriis et aliquibus responsoriis. Sablé-sur-Sarthe, France: Abbaye Saint-Pierre de Solesmes. 1983. ISBN 2-85274-076-1.

- Dearmer, Percy (1928). The Parson's Handbook, containing Practical Directions Both for Parsons and Others as to the Management of the Parish Church and Its Services According to the English Use, as Set Forth in the Book of Common Prayer (11th ed.). London, Edinburgh, etc.: Humphrey Milford.

- Bradshaw, Paul F. (Summer 2013). "The Daily Offices in the Prayer Book Tradition" (PDF). Anglican Theological Review. 95 (3): 447–60.

- Blunt, John Henry, ed. (1892). The Annotated Book of Common Prayer, being an Historical, Ritual, and Theological Commentary on the Devotional System of the Church of England (New ed.). London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

- Procter, Francis; Frere, Walter Howard (1910). A New History of the Book of Common Prayer, with a Rationale of Its Offices. London: Macmillan and Co, Ltd.

- Gee, Henry; Hardy, W. H. (1896). Documents Illustrative of English Church History. New York. pp. 417–42.

- The Shorter Prayer Book. London. 1948.

External links

- The orders for Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer according to the Book of Common Prayer as currently used in the Church of England