Nicholas Ferrar

Nicholas Ferrar (22 February 1592 – 4 December 1637) was an English scholar, courtier and businessman, who was ordained a deacon in the Church of England. He lost much of his fortune in the Virginia Company and retreated with his extended family in 1626 to the manor of Little Gidding, Huntingdonshire, for his remaining years, in an informal spiritual community following High Anglican practice.[1] His friend the poet and Anglican priest George Herbert (1593–1633), on his deathbed, sent Ferrar the manuscript of The Temple, telling him to publish the poetry if it might "turn to the advantage of any dejected poor soul." "If not, let him burn it; for I and it are less than the least of God's mercies."[2] Ferrar published them in 1633; they remain in print.

Nicholas Ferrar | |

|---|---|

Nicholas Ferrar, from a portrait by Cornelius Janssens, the original of which hangs in Magdalene College, Cambridge, alongside those of his parents. | |

| Deacon | |

| Born | 22 February 1592 London |

| Died | 4 December 1637 (aged 45) Little Gidding, Huntingdonshire |

| Venerated in | Anglican Communion |

| Feast | 4 December (Church of England), 1 December (Episcopal Church (US) and Southern Africa) |

Early life

Nicholas Ferrar was born in the City of London,[3] the third son and fifth child (of six) of Nicholas Ferrar and his wife Mary Ferrar (née Wodenoth). At the age of four he was sent to a nearby school, and is said to have been reading perfectly by the age of five. He was confirmed by the Bishop of London in 1598, contriving to have the bishop lay hands on him twice.[4] In 1600 he was sent away to boarding school in Berkshire, and in 1605, aged 13, he entered Clare Hall, Cambridge. He was elected a fellow-commoner at the end of his first year, took his BA in 1610 and elected a fellow the following year.[5]

Farrar first met George Herbert, known as a metaphysical poet, as a Cambridge undergraduate.

Travels abroad

Ferrar suffered from poor health and was advised to travel to continental Europe, away from the damp air of Cambridge. He obtained a position in the retinue of Princess Elizabeth, daughter of James I who married the Elector Frederick V. In April 1613 he left England with the princess, not returning until 1618.

By May he had left the Court to travel alone. Over the next few years he visited the Dutch Republic, Austria, Bohemia, Italy and Spain, learning to speak Dutch, German, Italian and Spanish. He studied at Leipzig and especially at Padua, where he continued his medical studies. He met Anabaptists and Roman Catholics, including Jesuits and Oratorians, as well as Jews, broadening his religious education. During this time Ferrar recorded many adventures in his letters home to his family and friends. In 1618 he is said to have had a vision that he was needed at home, and so he returned to England.[6]

The Virginia Company

The Ferrar family was deeply involved in the London Virginia Company. His family home was often visited by Sir Walter Raleigh, half-brother of Sir Humphrey Gilbert. Upon returning to London, Ferrar found that the family fortunes, primarily invested in Virginia, were under threat.

Ferrar entered the Parliament of England and worked with Sir Edwin Sandys. They were part of a parliamentary faction (the "country party" or "patriot party") that seized control of the government's finances from a rival "court faction", and were grouped around Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick. The court faction supported Sir Thomas Smythe (or Smith), also a prominent member of the East India Company. Smythe as treasurer of the Virginia Company from 1609 to 1620 encouraged the governor to end evangelisation of Native Americans and expand tobacco culture.[7]

Ferrar wrote a 16-page pamphlet criticising Smythe's management.[lower-alpha 1] Smythe (as he spelled his name) was heavily criticised by rivals for allegedly skimming profits, but an investigation revealed no wrongdoing and he continued to enjoy the support of the king.[9] The argument ended with the London Virginia Company losing its charter after a court decision in May 1624.

Ferrar served briefly as Member of Parliament for Lymington from 1624.

At Little Gidding

.jpg)

In 1626 Ferrar and his extended family left London and moved to the largely deserted village of Little Gidding in Huntingdonshire. The household was centred on the Ferrar family: Nicholas's mother, his brother John Ferrar (with his wife Bathsheba and their children), and his sister Susanna (and her husband John Collett and their children). They bought the manor of Little Gidding and restored the abandoned little church for their use. The household always had someone at prayer and had a strict routine. They tended to the health and education of local children. Ferrar and his family produced harmonies of the gospels that survive today as some of the finest in Britain. Many of the family also learned the art of bookbinding, apparently from the daughter of a Cambridge bookbinder, which style they worked in.[10][11]

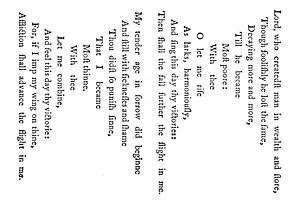

In 1633 the poet George Herbert, on his deathbed, sent the manuscript of The Temple to Nicholas Ferrar, telling him to publish the poems if he thought they might "turn to the advantage of any dejected poor soul", and otherwise, to burn them. Ferrar arranged to publish them that year. The Temple: Sacred Poems and Private Ejaculations (1633) had gone through eight editions by 1690.[12]

Nicholas Ferrar died on 4 December 1637, but the extended family continued their way of life without him. After his siblings John Ferrar and Susanna Ferrar Collett died in 1657 within a month of each other, the larger community began to disband.

Puritans criticised the life of the Ferrar household, denouncing them as Arminians, and saying they lived as in a "Protestant nunnery". However, the Ferrars never lived a formal religious life: there was no Rule, vows were not taken, and there was no enclosure. In this sense there was no "community" at Little Gidding, but rather a family living a Christian life in accordance with the Book of Common Prayer, according to High Church principles.

The fame of the Ferrar household was widespread, and attracted many visitors. Among them was King Charles I, who visited Little Gidding three times. He briefly took refuge there in 1645 after the Battle of Naseby.

Legacy and honours

Nicholas Ferrar is commemorated in the calendar of the Church of England on 4 December, the date of his death. In the calendar of the Episcopal Church in the United States, the Anglican Church of Southern Africa and the Church in Wales, he is commemorated on 1 December.

T. S. Eliot honoured Nicholas Ferrar in the Four Quartets, naming one of the quartets Little Gidding. The Friends of Little Gidding was founded in 1946 by Alan Maycock with the patronage of Eliot, to maintain and adorn the church at Little Gidding, and honour the life of Ferrar and his family and their place in the village. The Friends organise an annual pilgrimage to Ferrar's tomb, formerly held each July, but in recent years in May (the month when Eliot visited Little Gidding) and celebrate Nicholas Ferrar Day on the Saturday nearest 4 December.

A new religious community was founded at Little Gidding in the 1970s, inspired by the example of Ferrar. Called the Community of Christ the Sower, it disbanded in 1998. The Pilsdon Community in Dorset was also based on Ferrar's Little Gidding model.[14]

The former Poet Laureate, Ted Hughes was directly related to Nicholas Ferrar on his mother's side. Hughes and his wife, the poet Sylvia Plath, named their son Nicholas Farrar Hughes. The family evidently used both spellings of the surname.[15]

Nicholas Ferrar is regarded as the patron of the Oratory of the Good Shepherd, an international Anglican religious community.

References

Notes

- This pamphlet was presented to the members of the Roxburghe Club by the Duke of Devonshire, but it was not published until 1990. Ferrar alleged that Smith and his son-in-law, Alderman Robert Johnson, were running a company within a company to skim off the profits from the shareholders. He also alleged that Dr John Woodall had bought some Polish settlers as white slaves, and sold them again in Virginia to Lord de La Warr. Ferrar said that Smith was trying to reduce other colonists to slavery by extending their period of indenture indefinitely beyond the seventh year.[8]

Citations

- Wilson 1965.

- Maycock 1938, pp. 234–235.

- Maycock 1938, p. 6.

- Maycock 1938, p. 10.

- "Ferrar, Nicholas (FRR609N)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Maycock 1938.

- Hodgkins 2002, p. 156.

- Ferrar 1990.

- Sainsbury 1860, pp. 31–32.

- Horne 1894, p. 184.

- Harthan 1950, p. 13.

- Cox 2004, p. 92.

- Ferguson, Stallworthy & Salter 1996, p. 331.

- "History". Pilsdon.org.uk. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- Butscher 1976, p. 284.

Sources

- Butscher, Edward (1976). Sylvia Plath: Method and Madness. New York: Seabury Press. ISBN 978-0-671-80932-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cox, Michael, ed. (2004). The Concise Oxford Chronology of English Literature. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860634-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ferguson, Margaret W.; Salter, Mary Jo; Stallworthy, Jon, eds. (1996). The Norton Anthology of Poetry. W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-96820-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ferrar, Nicholas (1990). David R. Ransom (ed.). Sir Thomas Smith's Misgovernment of the Virginia Company by Nicholas Ferrar: A Manuscript from the Devonshire Papers at Chatsworth House. Roxburghe Club.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harthan, John P. (1950). Bookbindings. Victoria and Albert Museum. H. M. Stationery Office.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hodgkins, Christopher (2002). Reforming Empire: Protestant Colonialism and Conscience in British Literature. University of Missouri Press. p. 156. ISBN 978-0-8262-6294-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Horne, Herbert Percy (1894). The Binding of Books: An Essay in the History of Gold-tooled Bindings. K. Paul, Trench, Trübner. p. 184.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maycock, Alan Lawson (1938). Nicholas Ferrar of Little Gidding. S.P.C.K.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sainsbury, W Noel, ed. (1860). "America and West Indies: July 1622". Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies. Volume 1, 1574–1660. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. pp. 31–32. Retrieved 17 November 2017 – via British History Online.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wilson, Colin (1965). Beyond the Outsider: The Philosophy of the Future. Houghton Mifflin.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Ferrar, John; Ferrar, Jebb (1855). Mayor, John Eyton Bickersteth (ed.). Nicholas Ferrar. Two lives, by his brother John and by Doctor Jebb. Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Peckard, Peter (1790). Memoirs of the life of Mr. Nicholas Ferrar. Cambridge: Printed by J. Archdeacon.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shorthouse, Joseph Henry (1883). John Inglesant: A Romance. Macmillan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link), John Inglesant is a novel set in the 17th century, contains in Chapter IV a description and discussion of Ferrar and his family at Little Gidding.

- Willam, A. M. Conversations at Little Gidding. 'On the retirement of Charles V.' 'On the austere life': dialogues by members of the Ferrar family [transcribed by Nicholas Ferrar] with and introduction and notes. London: Cambridge University Press, 1970.

- Acland, John Edward. Little Gidding and Its Inmates in the Time of King Charles I. with an Account of the Harmonies – via Project Gutenberg.

- Counsell, Michael (2003). Every Pilgrim's Guide to England's Holy Places. Hymns Ancient and Modern. pp. 190–. ISBN 978-1-85311-522-6.

- Ferrar, Nicholas (1837). Turner, Francis; MacDonogh, The Revd Terence Michael (eds.). Brief memoirs of Nicholas Ferrar: founder of a Protestant religious establishment at Little Gidding, Huntingdonshire. London: Jas Nisbet.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maycock, Alan Lawson (1954). Chronicles of Little Gidding. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Ferrar, Nicholas (2 November 2006). Conversations at Little Gidding. Cambridge University Press. pp. 8–. ISBN 978-0-521-02821-9.

- Ransome, Joyce (2011). The Web of Friendship: Nicholas Ferrar and Little Gidding. Cambridge: James Clarke. ISBN 978-0-227-90090-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Riley, Kate E. (2007). The Good Old Way Revisited: The Ferrar Family of Little Gidding, c. 1625–1637 (PhD). The University of Western Australia.

- Skipton, Horace Pott Kennedy (1907). The Life and Times of Nicholas Ferrar. London: A. R. Mowbray.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ransome, David, The Ferrar Papers 1590–1790 in Magdalene College Cambridge Introduction/Finding List (PDF), Microfilm Academic Publishers

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Nicholas Ferrar |

| Parliament of England | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sir William Doddington Henry Crompton |

Member of Parliament for Lymington 1624 With: John More |

Succeeded by John Button John Mills |