Onyx

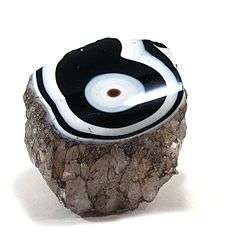

Onyx primarily refers to the parallel banded variety of the silicate mineral chalcedony. Agate and onyx are both varieties of layered chalcedony that differ only in the form of the bands: agate has curved bands and onyx has parallel bands. The colors of its bands range from black to almost every color. Commonly, specimens of onyx contain bands of black and/or white.[3] Onyx, as a descriptive term, has also been applied to parallel banded varieties of alabaster, marble, obsidian and opal, and misleadingly to materials with contorted banding, such as "Cave Onyx" and "Mexican Onyx".[4][5]

| Onyx | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Category | Oxide mineral |

| Formula (repeating unit) | Silica (silicon dioxide, SiO2) |

| Crystal system | Trigonal |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 60 g / mol |

| Color | Various |

| Cleavage | no cleavage |

| Fracture | Uneven, conchoidal |

| Mohs scale hardness | 6.5–7 |

| Luster | Vitreous, silky |

| Streak | White |

| Diaphaneity | Translucent |

| Specific gravity | 2.55–2.70 |

| Optical properties | Uniaxial/+ |

| Refractive index | 1.530 to 1.543 |

| References | [1][2] |

Etymology

Onyx comes through Latin (of the same spelling), from the Greek ὄνυξ, meaning "claw" or "fingernail". Onyx with flesh-colored and white bands can sometimes resemble a fingernail. The English word "nail" is cognate with the Greek word.[6]

Varieties

Onyx is formed of bands of chalcedony in alternating colors. It is cryptocrystalline, consisting of fine intergrowths of the silica minerals quartz and moganite. Its bands are parallel to one another, as opposed to the more chaotic banding that often occurs in agates.[7]

Sardonyx is a variant in which the colored bands are sard (shades of red) rather than black. Black onyx is perhaps the most famous variety, but is not as common as onyx with colored bands. Artificial treatments have been used since ancient times to produce both the black color in "black onyx" and the reds and yellows in sardonyx. Most "black onyx" on the market is artificially colored.[8][9]

Imitations and treatments

The name has also commonly been used to label other banded materials, such as banded calcite found in Mexico, India, and other places, and often carved, polished and sold. This material is much softer than true onyx, and much more readily available. The majority of carved items sold as "onyx" today are this carbonate material.[1][10]

Artificial onyx types have also been produced from common chalcedony and plain agates. The first-century naturalist Pliny the Elder described these techniques being used in Roman times.[11] Treatments for producing black and other colours include soaking or boiling chalcedony in sugar solutions, then treating with sulfuric or hydrochloric acid to carbonise sugars which had been absorbed into the top layers of the stone.[9][12] These techniques are still used, as well as other dyeing treatments, and most so-called "black onyx" sold is artificially treated.[13] In addition to dye treatments, heating and treatment with nitric acid have been used to lighten or eliminate undesirable colours.[9]

Geographic occurrence

Onyx is a gemstone found in various regions of the world including Yemen, Uruguay, Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, Czech Republic, Germany, India, Indonesia, Madagascar, Latin America, the UK, and various states in the US.[1]

Historic use

It has a long history of use for hardstone carving and jewelry, where it is usually cut as a cabochon or into beads. It has also been used for intaglio and hardstone cameo engraved gems, where the bands make the image contrast with the ground.[14] Some onyx is natural but much of the material in commerce is produced by the staining of agate.[15]

Onyx was used in Egypt as early as the Second Dynasty to make bowls and other pottery items.[16] Use of sardonyx appears in the art of Minoan Crete, notably from the archaeological recoveries at Knossos.[17]

Brazilian green onyx was often used as plinths for art deco sculptures created in the 1920s and 1930s. The German sculptor Ferdinand Preiss used Brazilian green onyx for the base on the majority of his chryselephantine sculptures.[18] Green onyx was also used for trays and pin dishes – produced mainly in Austria – often with small bronze animals or figures attached.[19]

Onyx is mentioned in the Bible many times.[20] Sardonyx (onyx in which white layers alternate with sard - a brownish color) is mentioned in the Bible as well.[21]

Onyx was known to the Ancient Greeks and Romans.[22] The first-century naturalist Pliny the Elder described both type of onyx and various artificial treatment techniques in his Naturalis Historia.[11]

Slabs of onyx (from the Atlas Mountains) were famously used by Mies van der Rohe in Villa Tugendhat at Brno (completed 1930) to create a shimmering semi-translucent interior wall.[23][24]

The Hôtel de la Païva in Paris is noted for its yellow onyx décor, and the new Mariinsky Theatre Second Stage in St.Petersburg uses yellow onyx in the lobby.

Superstitions

The ancient Romans entered battle carrying amulets of sardonyx engraved with Mars, the god of war. This was believed to bestow courage in battle. In Renaissance Europe, wearing sardonyx was believed to bestow eloquence.[25] A traditional Persian belief is that it helped with epilepsy.[26] Sardonyx was traditionally used by English midwives to ease childbirth by laying it between the breasts of the mother.[27]

See also

- Jasper – Chalcedony variety colored by iron oxide

- List of minerals – A list of minerals for which there are articles on Wikipedia

References

- "Onyx". mindat.org. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- "Onyx". gemdat.org. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- Lavinsky, Rob. "Onyx". mindat.org. Retrieved June 10, 2014.

- Manutchehr-Danai, Mohsen (2013). Dictionary of Gems and Gemology. New York: Springer. pp. 340–341. ISBN 9783662042885.

- Schumann, Walter (2009). Gemstones of the World. New York: Sterling. p. 158. ISBN 9781402768293.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". etymonline.com. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- Assaad, Fakhry A.; LaMoreaux, Philip E. Sr. (2004). Hughes, Travis H. (ed.). Field Methods for Geologists and Hydrogeologists. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 8. ISBN 3-540-40882-7.

- Sinkankas, John (1959). Gemstones of North America. 1. Princeton, New Jersey: Van Nostrand. p. 316.

- "The Manufacture of Gem Stones". Scientific American. New York, New York: Munn & Company: 49. 25 July 1874.

- Hurlbut, Cornelius S.; Sharp, W. Edwin (1998). Dana's Minerals and How to Study Them (4th ed.). New York, New York: Wiley. p. 200. ISBN 0-471-15677-9.

- O'Donoghue, Michael (1997). Synthetic, Imitation, and Treated Gemstones. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann. pp. 125–127. ISBN 0-7506-3173-2.

- Read, Peter G. (1999). Gemmology. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 160. ISBN 0-7506-4411-7.

- Liddicoat, Richard Thomas (1987). Handbook of Gem Identification (12th ed.). Santa Monica, California: Gemological Institute of America. pp. 158–160. ISBN 0-87311-012-9.

- Kraus, Edward Henry; Slawson, Chester Baker (1947). Gems and Gem Materials. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 227.

- Liddicoat, Richard Thomas; Copeland, Lawrence L. (1974). The Jewelers' Manual. Los Angeles, California: Gemological Institute of America. p. 87.

- Porter, Mary Winearls (1907). What Rome was Built with: A Description of the Stones Employed. Rome: H. Frowde. p. 108.

- C. Michael Hogan (2007) Knossos fieldnotes, The Modern Antiquarian

- "Ferdinand Preiss". Hickmet.com. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- "Lot 419, Schmidt-Hofer, Otto, 1873-1925 (Germany)". ArtValue.com.

- "BibleGateway". biblegateway.com. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- "BibleGateway". biblegateway.com. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- Administrator. "Onyx". gemstone.org. Retrieved 22 August 2015.

- "The Interiors". Villa Tugendhat. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- "Tugendhat Villa in Brno". UNESCO. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- Firefly Guide to Gems By Cally Oldershaw, p.168

- The Mining World, Volume 32, June 25, 1910, p.1267

- Three thousand years of mental healing By George Barton Cutten, 1911 P.202

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Onyx. |

- Rudler, Frederick William (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 20 (11th ed.). p. 118.