Comics

Comics is a medium used to express narratives or other ideas through images, usually combined with text. It typically takes the form of a sequence of panels of images. Textual devices such as speech balloons, captions, and onomatopoeia can indicate dialogue, narration, sound effects, or other information. The size and arrangement of panels contribute to narrative pacing. Cartooning and other forms of illustration are the most common image-making means in comics; fumetti is a form which uses photographic images. Common forms include gag-a-day comic strips, editorial and gag cartoons, and comic books. Since the late 20th century, bound volumes such as graphic novels, comic albums, and tankōbon have become increasingly common, while online webcomics have proliferated in the 21st century.

|

| Comics |

|---|

| Comics studies |

| Methods |

| Media Formats |

| Comics by Country and Culture |

| Community |

|

|

The history of comics has followed different paths in different cultures, but by the mid-20th century comics flourished, particularly in the United States, western Europe (especially France and Belgium), and Japan. The history of European comics is often traced to Rodolphe Töpffer's cartoon strips of the 1830s, but the medium truly became popular in the 1930s following the success of strips and books such as The Adventures of Tintin. American comics emerged as a mass medium in the early 20th century with the advent of newspaper comic strips; magazine-style comic books followed in the 1930s, in which the superhero genre became prominent after Superman appeared in 1938. Histories of Japanese comics and cartooning (manga) propose origins as early as the 12th century. Modern comic strips emerged in Japan in the early 20th century, and the output of comics magazines and books rapidly expanded in the post-World War II era (1945–) with the popularity of cartoonists such as Osamu Tezuka (Astro Boy, et al.). Comics has had a lowbrow reputation for much of its history, but towards the end of the 20th century began to find greater acceptance with the public and academics.

The term comics is used as a singular noun when it refers to the medium itself (e.g. "Comics is a visual art form."), but becomes plural when referring to works collectively (e.g. "Comics are popular reading material."). Though the term derives from the humorous (comic) work that predominated in early American newspaper comic strips, it has become standard for non-humorous works too. The alternate spelling comix – coined by the underground comix movement – is sometimes used to address these ambiguities.[1] In English, it is common to refer to the comics of different cultures by the terms used in their original languages, such as manga for Japanese comics, or bandes dessinées (B.D.) for French-language comics.

There is no consensus among theorists and historians on a definition of comics; some emphasize the combination of images and text, some sequentiality or other image relations, and others historical aspects, such as mass reproduction or the use of recurring characters. Increasing cross-pollination of concepts from different comics cultures and eras has only made definition more difficult.

Origins and traditions

- Examples of early comics

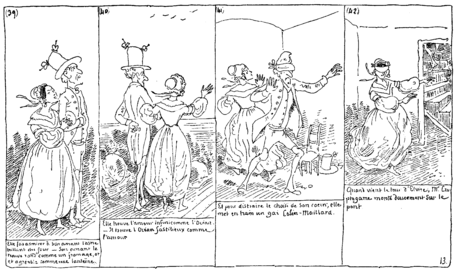

Histoire de Monsieur Cryptogame

Histoire de Monsieur Cryptogame

Rodolphe Töpffer, 1830

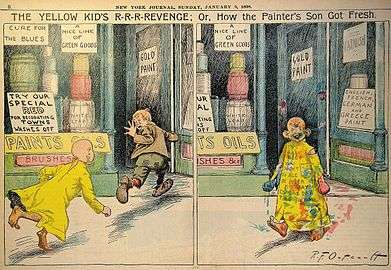

The European, American, and Japanese comics traditions have followed different paths.[2] Europeans have seen their tradition as beginning with the Swiss Rodolphe Töpffer from as early as 1827 and Americans have seen the origin of theirs in Richard F. Outcault's 1890s newspaper strip The Yellow Kid, though many Americans have come to recognize Töpffer's precedence.[3] Japan has a long history of satirical cartoons and comics leading up to the World War II era. The ukiyo-e artist Hokusai popularized the Japanese term for comics and cartooning, manga, in the early 19th century.[4] In the 1930s Harry "A" Chesler started a comics studio, which eventually at its height employed 40 artists working for 50 different publishers who helped make the comics medium flourish in "the Golden Age of Comics" after World War II.[5] In the post-war era modern Japanese comics began to flourish when Osamu Tezuka produced a prolific body of work.[6]Towards the close of the 20th century, these three traditions converged in a trend towards book-length comics: the comic album in Europe, the tankōbon[lower-alpha 1] in Japan, and the graphic novel in the English-speaking countries.[2]

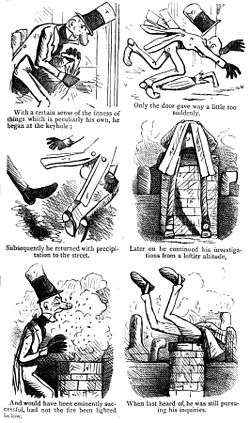

Outside of these genealogies, comics theorists and historians have seen precedents for comics in the Lascaux cave paintings[7] in France (some of which appear to be chronological sequences of images), Egyptian hieroglyphs, Trajan's Column in Rome,[8] the 11th-century Norman Bayeux Tapestry,[9] the 1370 bois Protat woodcut, the 15th-century Ars moriendi and block books, Michelangelo's The Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel,[8] and William Hogarth's 18th-century sequential engravings,[10] amongst others.[8][lower-alpha 2]

English-language comics

_-_comics_The_Upside_Downs_of_Little_Lady_Lovekins_and_Old_Man_Muffaroo_-_At_the_house_of_the_writing_pig.jpg)

Illustrated humour periodicals were popular in 19th-century Britain, the earliest of which was the short-lived The Glasgow Looking Glass in 1825. The most popular was Punch,[12] which popularized the term cartoon for its humorous caricatures.[13] On occasion the cartoons in these magazines appeared in sequences;[12] the character Ally Sloper featured in the earliest serialized comic strip when the character began to feature in its own weekly magazine in 1884.[14]

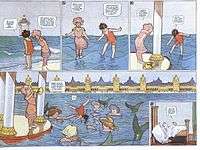

American comics developed out of such magazines as Puck, Judge, and Life. The success of illustrated humour supplements in the New York World and later the New York American, particularly Outcault's The Yellow Kid, led to the development of newspaper comic strips. Early Sunday strips were full-page[15] and often in colour. Between 1896 and 1901 cartoonists experimented with sequentiality, movement, and speech balloons.[16] A northworthy example is Gustave Verbeek, who wrote his comic series "The UpsideDowns of Old Man Muffaroo and Little Lady Lovekins" between 1903 and 1905. These comics were made in such a way that one could read the 6 panel comic, flip the book and keep reading. He made 64 such comics in total. In 2012 a remake of a selection of the comics was made by Marcus Ivarsson in the book 'In Uppåner med Lilla Lisen & Gamle Muppen'. (ISBN 978-91-7089-524-1)

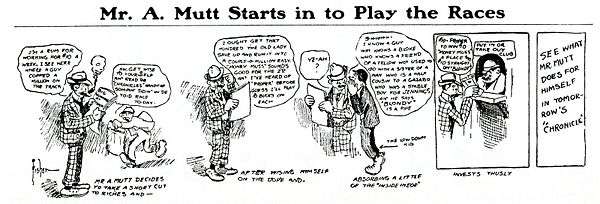

Shorter, black-and-white daily strips began to appear early in the 20th century, and became established in newspapers after the success in 1907 of Bud Fisher's Mutt and Jeff.[17] In Britain, the Amalgamated Press established a popular style of a sequence of images with text beneath them, including Illustrated Chips and Comic Cuts.[18] Humour strips predominated at first, and in the 1920s and 1930s strips with continuing stories in genres such as adventure and drama also became popular.[17]

Thin periodicals called comic books appeared in the 1930s, at first reprinting newspaper comic strips; by the end of the decade, original content began to dominate.[19] The success in 1938 of Action Comics and its lead hero Superman marked the beginning of the Golden Age of Comic Books, in which the superhero genre was prominent.[20] In the UK and the Commonwealth, the DC Thomson-created Dandy (1937) and Beano (1938) became successful humor-based titles, with a combined circulation of over 2 million copies by the 1950s. Their characters, including "Dennis the Menace", "Desperate Dan" and "The Bash Street Kids" have been read by generations of British schoolboys.[21] The comics originally experimented with superheroes and action stories before settling on humorous strips featuring a mix of the Amalgamated Press and US comic book styles.[22]

The popularity of superhero comic books declined following World War II,[23] while comic book sales continued to increase as other genres proliferated, such as romance, westerns, crime, horror, and humour.[24] Following a sales peak in the early 1950s, the content of comic books (particularly crime and horror) was subjected to scrutiny from parent groups and government agencies, which culminated in Senate hearings that led to the establishment of the Comics Code Authority self-censoring body.[25] The Code has been blamed for stunting the growth of American comics and maintaining its low status in American society for much of the remainder of the century.[26] Superheroes re-established themselves as the most prominent comic book genre by the early 1960s.[27] Underground comix challenged the Code and readers with adult, countercultural content in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[28] The underground gave birth to the alternative comics movement in the 1980s and its mature, often experimental content in non-superhero genres.[29]

Comics in the US has had a lowbrow reputation stemming from its roots in mass culture; cultural elites sometimes saw popular culture as threatening culture and society. In the latter half of the 20th century, popular culture won greater acceptance, and the lines between high and low culture began to blur. Comics nevertheless continued to be stigmatized, as the medium was seen as entertainment for children and illiterates.[30]

The graphic novel—book-length comics—began to gain attention after Will Eisner popularized the term with his book A Contract with God (1978).[31] The term became widely known with the public after the commercial success of Maus, Watchmen, and The Dark Knight Returns in the mid-1980s.[32] In the 21st century graphic novels became established in mainstream bookstores[33] and libraries[34] and webcomics became common.[35]

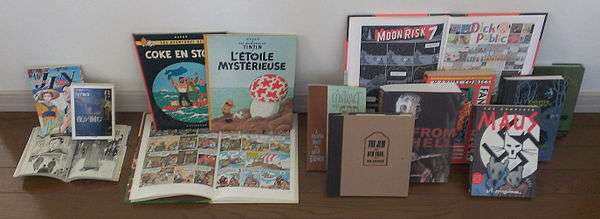

Franco-Belgian and European comics

The francophone Swiss Rodolphe Töpffer produced comic strips beginning in 1827,[8] and published theories behind the form.[36] Cartoons appeared widely in newspapers and magazines from the 19th century.[37] The success of Zig et Puce in 1925 popularized the use of speech balloons in European comics, after which Franco-Belgian comics began to dominate.[38] The Adventures of Tintin, with its signature clear line style,[39] was first serialized in newspaper comics supplements beginning in 1929,[40] and became an icon of Franco-Belgian comics.[41]

Following the success of Le Journal de Mickey (1934–44),[42] dedicated comics magazines[43] and full-colour comic albums became the primary outlet for comics in the mid-20th century.[44] As in the US, at the time comics were seen as infantile and a threat to culture and literacy; commentators stated that "none bear up to the slightest serious analysis",[lower-alpha 3] and that comics were "the sabotage of all art and all literature".[46][lower-alpha 4]

In the 1960s, the term bandes dessinées ("drawn strips") came into wide use in French to denote the medium.[47] Cartoonists began creating comics for mature audiences,[48] and the term "Ninth Art"[lower-alpha 5] was coined, as comics began to attract public and academic attention as an artform.[49] A group including René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo founded the magazine Pilote in 1959 to give artists greater freedom over their work. Goscinny and Uderzo's The Adventures of Asterix appeared in it[50] and went on to become the best-selling French-language comics series.[51] From 1960, the satirical and taboo-breaking Hara-Kiri defied censorship laws in the countercultural spirit that led to the May 1968 events.[52]

Frustration with censorship and editorial interference led to a group of Pilote cartoonists to found the adults-only L'Écho des savanes in 1972. Adult-oriented and experimental comics flourished in the 1970s, such as in the experimental science fiction of Mœbius and others in Métal hurlant, even mainstream publishers took to publishing prestige-format adult comics.[53]

From the 1980s, mainstream sensibilities were reasserted and serialization became less common as the number of comics magazines decreased and many comics began to be published directly as albums.[54] Smaller publishers such as L'Association[55] that published longer works[56] in non-traditional formats[57] by auteur-istic creators also became common. Since the 1990s, mergers resulted in fewer large publishers, while smaller publishers proliferated. Sales overall continued to grow despite the trend towards a shrinking print market.[58]

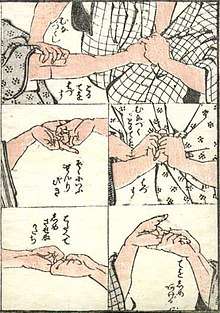

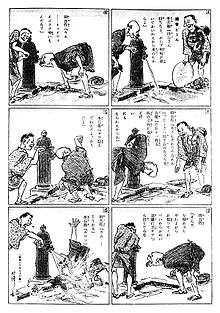

Japanese comics

Japanese comics and cartooning (manga),[lower-alpha 7] have a history that has been seen as far back as the anthropomorphic characters in the 12th-to-13th-century Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga, 17th-century toba-e and kibyōshi picture books,[62] and woodblock prints such as ukiyo-e which were popular between the 17th and 20th centuries. The kibyōshi contained examples of sequential images, movement lines,[63] and sound effects.[64]

Illustrated magazines for Western expatriates introduced Western-style satirical cartoons to Japan in the late 19th century. New publications in both the Western and Japanese styles became popular, and at the end of the 1890s, American-style newspaper comics supplements began to appear in Japan,[65] as well as some American comic strips.[62] 1900 saw the debut of the Jiji Manga in the Jiji Shinpō newspaper—the first use of the word "manga" in its modern sense,[61] and where, in 1902, Rakuten Kitazawa began the first modern Japanese comic strip.[66] By the 1930s, comic strips were serialized in large-circulation monthly girls' and boys' magazine and collected into hardback volumes.[67]

The modern era of comics in Japan began after World War II, propelled by the success of the serialized comics of the prolific Osamu Tezuka[68] and the comic strip Sazae-san.[69] Genres and audiences diversified over the following decades. Stories are usually first serialized in magazines which are often hundreds of pages thick and may contain over a dozen stories;[70] they are later compiled in tankōbon-format books.[71] At the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, nearly a quarter of all printed material in Japan was comics.[72] Translations became extremely popular in foreign markets—in some cases equaling or surpassing the sales of domestic comics.[73]

Forms and formats

Comic strips are generally short, multipanel comics that traditionally most commonly appeared in newspapers. In the US, daily strips have normally occupied a single tier, while Sunday strips have been given multiple tiers. In the early 20th century, daily strips were typically in black-and-white and Sundays were usually in colour and often occupied a full page.[74]

Specialized comics periodicals formats vary greatly in different cultures. Comic books, primarily an American format, are thin periodicals[75] usually published in colour.[76] European and Japanese comics are frequently serialized in magazines—monthly or weekly in Europe,[61] and usually black-and-white and weekly in Japan.[77] Japanese comics magazine typically run to hundreds of pages.[78]

Book-length comics take different forms in different cultures. European comic albums are most commonly printed in A4-size[79] colour volumes.[44] In English-speaking countries, the trade paperback format originating from collected comic books have also been chosen for original material. Otherwise, bound volumes of comics are called graphic novels and are available in various formats. Despite incorporating the term "novel"—a term normally associated with fiction—"graphic novel" also refers to non-fiction and collections of short works.[80] Japanese comics are collected in volumes called tankōbon following magazine serialization.[81]

Gag and editorial cartoons usually consist of a single panel, often incorporating a caption or speech balloon. Definitions of comics which emphasize sequence usually exclude gag, editorial, and other single-panel cartoons; they can be included in definitions that emphasize the combination of word and image.[82] Gag cartoons first began to proliferate in broadsheets published in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the term "cartoon"[lower-alpha 8] was first used to describe them in 1843 in the British humour magazine Punch.[13]

Webcomics are comics that are available on the internet. They are able to reach large audiences, and new readers usually can access archived installments.[83] Webcomics can make use of an infinite canvas—meaning they are not constrained by size or dimensions of a page.[84]

Some consider storyboards[85] and wordless novels to be comics.[86] Film studios, especially in animation, often use sequences of images as guides for film sequences. These storyboards are not intended as an end product and are rarely seen by the public.[85] Wordless novels are books which use sequences of captionless images to deliver a narrative.[87]

Art styles

While almost all comics art is in some sense abbreviated, and also while every artist who has produced comics work brings their own individual approach to bear, some broader art styles have been identified. Comic strip artists Cliff Sterrett, Frank King, and Gus Arriola often used unusual, colorful backgrounds, sometimes veering into abstract art.

The basic styles have been identified as realistic and cartoony, with a huge middle ground for which R. Fiore has coined the phrase liberal. Fiore has also expressed distaste with the terms realistic and cartoony, preferring the terms literal and freestyle, respectively.[88]

Scott McCloud has created "The Big Triangle"[89] as a tool for thinking about comics art. He places the realistic representation in the bottom left corner, with iconic representation, or cartoony art, in the bottom right, and a third identifier, abstraction of image, at the apex of the triangle. This allows placement and grouping of artists by triangulation.

- The cartoony style uses comic effects and a variation of line widths for expression. Characters tend to have rounded, simplified anatomy. Noted exponents of this style are Carl Barks and Jeff Smith.[88]

- The realistic style, also referred to as the adventure style is the one developed for use within the adventure strips of the 1930s. They required a less cartoony look, focusing more on realistic anatomy and shapes, and used the illustrations found in pulp magazines as a basis. This style became the basis of the superhero comic book style since Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel originally worked Superman up for publication as an adventure strip.[90]

McCloud also notes that in several traditions, there is a tendency to have the main characters drawn rather simplistic and cartoony, while the backgrounds and environment are depicted realistically. Thus, he argues, the reader easily identifies with the characters, (as they are similar to one's idea of self), whilst being immersed into a world, that's three-dimensional and textured.[91] Good examples of this phenomenon include Hergé's The Adventures of Tintin (in his "personal trademark" Ligne claire style), Will Eisner's Spirit and Osamu Tezuka's Buddha, among many others.

Comics studies

R. C. Harvey, 2001[82]

Similar to the problems of defining literature and film,[92] no consensus has been reached on a definition of the comics medium,[93] and attempted definitions and descriptions have fallen prey to numerous exceptions.[94] Theorists such as Töpffer,[95] R.C. Harvey, Will Eisner,[96] David Carrier,[97] Alain Rey,[93] and Lawrence Grove emphasize the combination of text and images,[98] though there are prominent examples of pantomime comics throughout its history.[94] Other critics, such as Thierry Groensteen[98] and Scott McCloud, have emphasized the primacy of sequences of images.[99] Towards the close of the 20th century, different cultures' discoveries of each other's comics traditions, the rediscovery of forgotten early comics forms, and the rise of new forms made defining comics a more complicated task.[100]

European comics studies began with Töpffer's theories of his own work in the 1840s, which emphasized panel transitions and the visual–verbal combination. No further progress was made until the 1970s.[101] Pierre Fresnault-Deruelle then took a semiotics approach to the study of comics, analyzing text–image relations, page-level image relations, and image discontinuities, or what Scott McCloud later dubbed "closure".[102] In 1987, Henri Vanlier introduced the term multicadre, or "multiframe", to refer to the comics page as a semantic unit.[103] By the 1990s, theorists such as Benoît Peeters and Thierry Groensteen turned attention to artists' poïetic creative choices.[102] Thierry Smolderen and Harry Morgan have held relativistic views of the definition of comics, a medium that has taken various, equally valid forms over its history. Morgan sees comics as a subset of "les littératures dessinées" (or "drawn literatures").[100] French theory has come to give special attention to the page, in distinction from American theories such as McCloud's which focus on panel-to-panel transitions.[103] Since the mid-2000s, Neil Cohn has begun analyzing how comics are understood using tools from cognitive science, extending beyond theory by using actual psychological and neuroscience experiments. This work has argued that sequential images and page layouts both use separate rule-bound "grammars" to be understood that extend beyond panel-to-panel transitions and categorical distinctions of types of layouts, and that the brain's comprehension of comics is similar to comprehending other domains, such as language and music.[104]

Historical narratives of manga tend to focus either on its recent, post-WWII history, or on attempts to demonstrate deep roots in the past, such as to the Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga picture scroll of the 12th and 13th centuries, or the early 19th-century Hokusai Manga.[105] The first historical overview of Japanese comics was Seiki Hosokibara's Nihon Manga-Shi[lower-alpha 9] in 1924.[106] Early post-war Japanese criticism was mostly of a left-wing political nature until the 1986 publication of Tomofusa Kure's Modern Manga: The Complete Picture,[lower-alpha 10] which de-emphasized politics in favour of formal aspects, such as structure and a "grammar" of comics. The field of manga studies increased rapidly, with numerous books on the subject appearing in the 1990s.[107] Formal theories of manga have focused on developing a "manga expression theory",[lower-alpha 11] with emphasis on spatial relationships in the structure of images on the page, distinguishing the medium from film or literature, in which the flow of time is the basic organizing element.[108] Comics studies courses have proliferated at Japanese universities, and Japan Society for Studies in Cartoon and Comics[lower-alpha 12] was established in 2001 to promote comics scholarship.[109] The publication of Frederik L. Schodt's Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics in 1983 led to the spread of use of the word manga outside Japan to mean "Japanese comics" or "Japanese-style comics".[110]

.jpg)

Coulton Waugh attempted the first comprehensive history of American comics with The Comics (1947).[111] Will Eisner's Comics and Sequential Art (1985) and Scott McCloud's Understanding Comics (1993) were early attempts in English to formalize the study of comics. David Carrier's The Aesthetics of Comics (2000) was the first full-length treatment of comics from a philosophical perspective.[112] Prominent American attempts at definitions of comics include Eisner's, McCloud's, and Harvey's. Eisner described what he called "sequential art" as "the arrangement of pictures or images and words to narrate a story or dramatize an idea";[113] Scott McCloud defined comics as "juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer",[114] a strictly formal definition which detached comics from its historical and cultural trappings.[115] R.C. Harvey defined comics as "pictorial narratives or expositions in which words (often lettered into the picture area within speech balloons) usually contribute to the meaning of the pictures and vice versa".[116] Each definition has had its detractors. Harvey saw McCloud's definition as excluding single-panel cartoons,[117] and objected to McCloud's de-emphasizing verbal elements, insisting "the essential characteristic of comics is the incorporation of verbal content".[103] Aaron Meskin saw McCloud's theories as an artificial attempt to legitimize the place of comics in art history.[96]

Cross-cultural study of comics is complicated by the great difference in meaning and scope of the words for "comics" in different languages.[118] The French term for comics, bandes dessinées ("drawn strip") emphasizes the juxtaposition of drawn images as a defining factor,[119] which can imply the exclusion of even photographic comics.[120] The term manga is used in Japanese to indicate all forms of comics, cartooning,[121] and caricature.[122]

Terminology

The term comics refers to the comics medium when used as an uncountable noun and thus takes the singular: "comics is a medium" rather than "comics are a medium". When comic appears as a countable noun it refers to instances of the medium, such as individual comic strips or comic books: "Tom's comics are in the basement."[123]

Panels are individual images containing a segment of action,[124] often surrounded by a border.[125] Prime moments in a narrative are broken down into panels via a process called encapsulation.[126] The reader puts the pieces together via the process of closure by using background knowledge and an understanding of panel relations to combine panels mentally into events.[127] The size, shape, and arrangement of panels each affect the timing and pacing of the narrative.[128] The contents of a panel may be asynchronous, with events depicted in the same image not necessarily occurring at the same time.[129]

Text is frequently incorporated into comics via speech balloons, captions, and sound effects. Speech balloons indicate dialogue (or thought, in the case of thought balloons), with tails pointing at their respective speakers.[130] Captions can give voice to a narrator, convey characters' dialogue or thoughts,[131] or indicate place or time.[132] Speech balloons themselves are strongly associated with comics, such that the addition of one to an image is sufficient to turn the image into comics.[133] Sound effects mimic non-vocal sounds textually using onomatopoeia sound-words.[134]

Cartooning is most frequently used in making comics, traditionally using ink (especially India ink) with dip pens or ink brushes;[135] mixed media and digital technology have become common. Cartooning techniques such as motion lines[136] and abstract symbols are often employed.[137]

While comics are often the work of a single creator, the labour of making them is frequently divided between a number of specialists. There may be separate writers and artists, and artists may specialize in parts of the artwork such as characters or backgrounds, as is common in Japan.[138] Particularly in American superhero comic books,[139] the art may be divided between a penciller, who lays out the artwork in pencil;[140] an inker, who finishes the artwork in ink;[141] a colourist;[142] and a letterer, who adds the captions and speech balloons.[143]

Etymology

The English-language term comics derives from the humorous (or "comic") work which predominated in early American newspaper comic strips; usage of the term has become standard for non-humorous works as well. The term "comic book" has a similarly confusing history: they are most often not humorous; nor are they regular books, but rather periodicals.[144] It is common in English to refer to the comics of different cultures by the terms used in their original languages, such as manga for Japanese comics, or bandes dessinées for French-language Franco-Belgian comics.[145]

Many cultures have taken their words for comics from English, including Russian (Комикс, komiks)[146] and German (comic).[147] Similarly, the Chinese term manhua[148] and the Korean manhwa[149] derive from the Chinese characters with which the Japanese term manga is written.[150]

See also

See also lists

- List of best-selling comic series

- List of best-selling manga

- List of comic books

- List of comics by country

- List of comics creators

- List of comics publishing companies

- List of comic strip syndicates

- List of Franco-Belgian comics series

- List of newspaper comic strips

- Lists of manga

- List of manga artists

- List of manga magazines

- List of manga publishers

- List of years in comics

Notes

- tankōbon (単行本, translation close to "independently appearing book")

- David Kunzle has compiled extensive collections of these and other proto-comics in his The Early Comic Strip (1973) and The History of the Comic Strip (1990).[11]

- French: "... aucune ne supporte une analyse un peu serieuse." – Jacqueline & Raoul Dubois in La Presse enfantine française (Midol, 1957)[45]

- French: "C'est le sabotage de tout art et de toute littérature." – Jean de Trignon in Histoires de la littérature enfantine de ma Mère l'Oye au Roi Babar (Hachette, 1950)[45]

- French: neuvième art

- Tagosaku and Mokube Sightseeing in Tokyo (Japanese: 田吾作と杢兵衛の東京見物, Hepburn: Tagosaku to Mokube no Tokyo Kenbutsu)

- "Manga" (Japanese: 漫画) can be glossed in many ways, amongst them "whimsical pictures", "disreputable pictures",[59] "irresponsible pictures",[60] "derisory pictures", and "sketches made for or out of a sudden inspiration".[61]

- "cartoon": from the Italian cartone, meaning "card", which referred to the cardboard on which the cartoons were typically drawn.[13]

- Hosokibara, Seiki (1924). 日本漫画史 [Japanese Comics History]. Yuzankaku.

- Kure, Tomofusa (1986). 現代漫画の全体像 [Modern Manga: The Complete Picture]. Joho Center Publishing. ISBN 978-4-575-71090-8.[107]

- "Manga expression theory" (Japanese: 漫画表現論, Hepburn: manga hyōgenron)[108]

- Japan Society for Studies in Cartoon and Comics (Japanese: 日本マンガ学会, Hepburn: Nihon Manga Gakkai)

References

- Gomez Romero, Luis; Dahlman, Ian (2012-01-01). "Introduction - Justice framed: law in comics and graphic novels". Law Text Culture. 16 (1): 3–32.

- Couch 2000.

- Gabilliet 2010, p. xiv; Beerbohm 2003; Sabin 2005, p. 186; Rowland 1990, p. 13.

- Petersen 2010, p. 41; Power 2009, p. 24; Gravett 2004, p. 9.

- Ewing, Emma Mai (1976-09-12). "The 'Funnies'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2018-11-28. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- Couch 2000; Petersen 2010, p. 175.

- Gabilliet 2010, p. xiv; Barker 1989, p. 6; Groensteen 2014; Grove 2010, p. 59; Beaty 2012; Jobs 2012, p. 98.

- Gabilliet 2010, p. xiv.

- Gabilliet 2010, p. xiv; Beaty 2012, p. 61; Grove 2010, pp. 16, 21, 59.

- Grove 2010, p. 79.

- Beaty 2012, p. 62.

- Clark & Clark 1991, p. 17.

- Harvey 2001, p. 77.

- Meskin & Cook 2012, p. xxii.

- Nordling 1995, p. 123.

- Gordon 2002, p. 35.

- Harvey 1994, p. 11.

- Bramlett, Cook & Meskin 2016, p. 45.

- Rhoades 2008, p. 2.

- Rhoades 2008, p. x.

- Childs & Storry 2013, p. 532.

- Bramlett, Cook & Meskin 2016, p. 46.

- Gabilliet 2010, p. 51.

- Gabilliet 2010, p. 49.

- Gabilliet 2010, pp. 49–50.

- Gabilliet 2010, p. 50.

- Gabilliet 2010, pp. 52–55.

- Gabilliet 2010, p. 66.

- Hatfield 2005, pp. 20, 26; Lopes 2009, p. 123; Rhoades 2008, p. 140.

- Lopes 2009, pp. xx–xxi.

- Petersen 2010, p. 222.

- Kaplan 2008, p. 172; Sabin 1993, p. 246; Stringer 1996, p. 262; Ahrens & Meteling 2010, p. 1; Williams & Lyons 2010, p. 7.

- Gabilliet 2010, pp. 210–211.

- Lopes 2009, p. 151–152.

- Thorne 2010, p. 209.

- Harvey 2010.

- Lefèvre 2010, p. 186.

- Vessels 2010, p. 45; Miller 2007, p. 17.

- Screech 2005, p. 27; Miller 2007, p. 18.

- Miller 2007, p. 17.

- Theobald 2004, p. 82; Screech 2005, p. 48; McKinney 2011, p. 3.

- Grove 2005, pp. 76–78.

- Petersen 2010, pp. 214–215; Lefèvre 2010, p. 186.

- Petersen 2010, pp. 214–215.

- Grove 2005, p. 46.

- Grove 2005, pp. 45–46.

- Grove 2005, p. 51.

- Miller 1998, p. 116; Lefèvre 2010, p. 186.

- Miller 2007, p. 23.

- Miller 2007, p. 21.

- Screech 2005, p. 204.

- Miller 2007, p. 22.

- Miller 2007, pp. 25–28.

- Miller 2007, pp. 33–34.

- Beaty 2007, p. 9.

- Lefèvre 2010, pp. 189–190.

- Grove 2005, p. 153.

- Miller 2007, pp. 49–53.

- Karp & Kress 2011, p. 19.

- Gravett 2004, p. 9.

- Johnson-Woods 2010, p. 22.

- Schodt 1996, p. 22.

- Mansfield 2009, p. 253.

- Petersen 2010, p. 42.

- Johnson-Woods 2010, pp. 21–22.

- Petersen 2010, p. 128; Gravett 2004, p. 21.

- Schodt 1996, p. 22; Johnson-Woods 2010, pp. 23–24.

- Gravett 2004, p. 24.

- MacWilliams 2008, p. 3; Hashimoto & Traphagan 2008, p. 21; Sugimoto 2010, p. 255; Gravett 2004, p. 8.

- Schodt 1996, p. 23; Gravett 2004, pp. 13–14.

- Gravett 2004, p. 14.

- Brenner 2007, p. 13; Lopes 2009, p. 152; Raz 1999, p. 162; Jenkins 2004, p. 121.

- Lee 2010, p. 158.

- Booker 2014, p. xxvi–xxvii.

- Orr 2008, p. 11; Collins 2010, p. 227.

- Orr 2008, p. 10.

- Schodt 1996, p. 23; Orr 2008, p. 10.

- Schodt 1996, p. 23.

- Grove 2010, p. 24; McKinney 2011.

- Goldsmith 2005, p. 16; Karp & Kress 2011, pp. 4–6.

- Poitras 2001, p. 66–67.

- Harvey 2001, p. 76.

- Petersen 2010, pp. 234–236.

- Petersen 2010, p. 234; McCloud 2000, p. 222.

- Rhoades 2008, p. 38.

- Beronä 2008, p. 225.

- Cohen 1977, p. 181.

- Fiore 2010.

- "The Big Triangle". scottmccloud.com. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- Santos, 1998. The Golden Era... June 1938 to 1945, Part I

- McCloud 1993, p. 48.

- Groensteen 2012, pp. 128—129.

- Groensteen 2012, p. 124.

- Groensteen 2012, p. 126.

- Thomas 2010, p. 158.

- Beaty 2012, p. 65.

- Groensteen 2012, pp. 126, 131.

- Grove 2010, pp. 17–19.

- Thomas 2010, pp. 157, 170.

- Groensteen 2012, pp. 112–113.

- Miller 2007, p. 101.

- Groensteen 2012, p. 112.

- Groensteen 2012, p. 113.

- Cohn 2013.

- Stewart 2014, pp. 28–29.

- Johnson-Woods 2010, p. 23; Stewart 2014, p. 29.

- Kinsella 2000, pp. 96–97.

- Kinsella 2000, p. 100.

- Morita 2010, pp. 37–38.

- Stewart 2014, p. 30.

- Inge 1989, p. 214.

- Meskin & Cook 2012, p. xxix.

- Yuan 2011; Eisner 1985, p. 5.

- Kovacs & Marshall 2011, p. 10; Holbo 2012, p. 13; Harvey 2010, p. 1; Beaty 2012, p. 6; McCloud 1993, p. 9.

- Beaty 2012, p. 67.

- Chute 2010, p. 7; Harvey 2001, p. 76.

- Harvey 2010, p. 1.

- Morita 2010, p. 33.

- Groensteen 2012, p. 130; Morita 2010, p. 33.

- Groensteen 2012, p. 130.

- Johnson-Woods 2010, p. 336.

- Morita & ppp2010, p. 33.

- Chapman 2012, p. 8; Chute & DeKoven 2012, p. 175; Fingeroth 2008, p. 4.

- Lee 1978, p. 15.

- Eisner 1985, pp. 28, 45.

- Duncan & Smith 2009, p. 10.

- Duncan & Smith 2009, p. 316.

- Eisner 1985, p. 30.

- Duncan & Smith 2009, p. 315; Karp & Kress 2011, p. 12–13.

- Lee 1978, p. 15; Markstein 2010; Eisner 1985, p. 157; Dawson 2010, p. 112; Saraceni 2003, p. 9.

- Lee 1978, p. 15; Lyga & Lyga 2004.

- Saraceni 2003, p. 9; Karp & Kress 2011, p. 18.

- Forceville, Veale & Feyaerts 2010, p. 56.

- Duncan & Smith 2009, pp. 156, 318.

- Markstein 2010; Lyga & Lyga 2004, p. 161; Lee 1978, p. 145; Rhoades 2008, p. 139.

- Bramlett 2012, p. 25; Guigar 2010, p. 126; Cates 2010, p. 98.

- Goldsmith 2005, p. 21; Karp & Kress 2011, p. 13–14.

- O'Nale 2010, p. 384.

- Tondro 2011, p. 51.

- Lyga & Lyga 2004, p. 161.

- Markstein 2010; Lyga & Lyga 2004, p. 161; Lee 1978, p. 145.

- Duncan & Smith 2009, p. 315.

- Lyga & Lyga 2004, p. 163.

- Groensteen 2012, p. 131 (translator's note).

- McKinney 2011, p. xiii.

- Alaniz 2010, p. 7.

- Frahm 2003.

- Wong 2002, p. 11; Cooper-Chen 2010, p. 177.

- Johnson-Woods 2010, p. 301.

- Cooper-Chen 2010, p. 177; Thompson 2007, p. xiii.

Works cited

Books

- Ahrens, Jörn; Meteling, Arno (2010). Comics and the City: Urban Space in Print, Picture, and Sequence. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-4019-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Alaniz, José (2010). Komiks: Comic Art in Russia. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-366-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barker, Martin (1989). Comics: Ideology, Power, and the Critics. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-2589-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beaty, Bart (2007). Unpopular Culture: Transforming the European Comic Book in The 1990s. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-9412-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beaty, Bart (2012). Comics Versus Art. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-9627-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beronä, David A. (2008). Wordless Books: The Original Graphic Novels. Abrams Books. ISBN 978-0-8109-9469-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Booker, M. Keith, ed. (2014). "Introduction". Comics through Time: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas. ABC-CLIO. pp. xxv–xxxvii. ISBN 978-0-313-39751-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bramlett, Frank (2012). Linguistics and the Study of Comics. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-36282-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bramlett, Frank; Cook, Roy; Meskin, Aaron, eds. (2016). The Routledge Companion to Comics. Routledge. pp. 45–6. ISBN 978-1-317-91538-6.

- Brenner, Robin E. (2007). Understanding Manga and Anime. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-09448-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cates, Isaac (2010). "Comic and the Grammar of Diagrams". In Ball, David M.; Kuhlman, Martha B. (eds.). The Comics of Chris Ware: Drawing Is a Way of Thinking. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 90–105. ISBN 978-1-60473-442-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chapman, Robyn (2012). Drawing Comics Lab: 52 Exercises on Characters, Panels, Storytelling, Publishing & Professional Practices. Quarry Books. ISBN 978-1-61058-629-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Childs, Peter; Storry, Michael (2013). Encyclopedia of Contemporary British Culture. Routledge. p. 532. ISBN 978-1-134-75555-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chute, Hillary L (2010). Graphic Women: Life Narrative and Contemporary Comics. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-15062-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chute, Hillary; DeKoven, Marianne (2012). "Comic books and graphic novels". In Glover, David; McCracken, Scott (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Popular Fiction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 175–195. ISBN 978-0-521-51337-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clark, Alan; Clark, Laurel (1991). Comics: An Illustrated History. Green Wood. ISBN 978-1-872532-55-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cohn, Neil (2013). The Visual Language of Comics: Introduction to the Structure and Cognition of Sequential Images. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4411-8145-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collins, Rachel (2010). "Drawing Comics into Canadian Libraries". In Weiner, Robert G. (ed.). Graphic Novels and Comics in Libraries and Archives. McFarland & Company. pp. 226–241. ISBN 978-0-7864-5693-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cooper-Chen, Anne M. (2010). Cartoon Cultures: The Globalization of Japanese Popular Media. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1-4331-0368-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dawson, Willow (2010). Lila & Ecco's Do-It-Yourself Comics Club. Kids Can Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1-55453-438-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duncan, Randy; Smith, Matthew J (2009). The Power of Comics. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-2936-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Eisner, Will (1985). Comics and Sequential Art. Poorhouse Press. ISBN 978-0-9614728-0-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fingeroth, Danny (2008). The Rough Guide to Graphic Novels. Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-84353-993-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Forceville, Charles; Veale, Tony; Feyaerts, Kurt (2010). "Balloonics: The Visuals of Balloons in Comics". In Goggin, Joyce; Hassler-Forest, Dan (eds.). The Rise and Reason of Comics and Graphic Literature: Critical Essays on the Form. McFarland & Company. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-7864-4294-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gabilliet, Jean-Paul (2010). Of Comics and Men: A Cultural History of American Comic Books. translated from French by Bart Beaty and Nick Nguyen. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-267-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Goldsmith, Francisca (2005). Graphic Novels Now: Building, Managing, And Marketing a Dynamic Collection. American Library Association. ISBN 978-0-8389-0904-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gordon, Ian (2002). Comic Strips and Consumer Culture. Smithsonian. ISBN 978-1-58834-031-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gravett, Paul (2004). Manga: 60 Years of Japanese Comics. Laurence King Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85669-391-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Groensteen, Thierry (2012) [Originally published in French in 1999]. "The Impossible Definition". In Heer, Jeet; Worcester, Kent (eds.). A Comics Studies Reader. translated by Bart Beaty. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 124–131. ISBN 978-1-60473-109-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grove, Laurence (2005). Text/Image Mosaics in French Culture: Emblems and Comic Strips. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-3488-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grove, Laurence (2010). Comics in French: The European Bande Dessinée in Context. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-588-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guigar, Brad J. (2010). The Everything Cartooning Book: Create Unique And Inspired Cartoons For Fun And Profit. Adams Media. ISBN 978-1-4405-2306-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harvey, R.C. (1994). The Art of the Funnies: An Aesthetic History. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-0-87805-674-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harvey, R.C. (2001). "Comedy at the Juncture of Word and Image". In Varnum, Robin; Gibbons, Christina T. (eds.). The Language of Comics: Word and Image. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 75–96. ISBN 978-1-57806-414-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hashimoto, Akiko; Traphagan, John W. (2008). Imagined Families, Lived Families: Culture and Kinship in Contemporary Japan. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7577-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hatfield, Charles (2005). Alternative Comics: An Emerging Literature. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-719-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Holbo, John (2012). "Redefining Comics". In Meskin, Aaron; Cook, Roy T. (eds.). The Art of Comics: A Philosophical Approach. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 3–30. ISBN 978-1-4443-3464-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Inge, Thomas M. (1989). Handbook of American Popular Culture. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-25406-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jenkins, Henry (2004). "Pop Cosmopolitanism: Mapping Cultural Flows in an Age of Media Convergence". In Suárez-Orozco, Marcelo M.; Qin-Hilliard, Desirée Baolian (eds.). Globalization: Culture and Education for a New Millennium. University of California Press. pp. 114–140. ISBN 978-0-520-24125-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jobs, Richard Ivan (2012). "Tarzan under Attack". In Wannamaker, Annette; Abate, Michelle Ann (eds.). Global Perspectives on Tarzan: From King of the Jungle to International Icon. Routledge. pp. 73–106. ISBN 978-1-136-44791-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johnson-Woods, Toni (2010). Manga: An Anthology of Global and Cultural Perspectives. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-2938-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaplan, Arie (2008). From Krakow to Krypton: Jews and Comic Books. Jewish Publication Society. ISBN 978-0-8276-0843-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Karp, Jesse; Kress, Rush (2011). Graphic Novels in Your School Library. American Library Association. ISBN 978-0-8389-1089-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kinsella, Sharon (2000). Adult Manga: Culture & Power in Contemporary Japanese Society. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2318-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kovacs, George; Marshall, C.W. (2011). Classics and Comics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-979290-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Hye-Kyung (2010). "Between Fan Culture and Copyright Infringement: Manga Scanlation". In O'Reilly, Daragh; Kerrigan, Finola (eds.). Marketing the Arts: A Fresh Approach. Taylor & Francis. pp. 153–170. ISBN 978-0-415-49685-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Stan (1978). How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-53077-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lopes, Paul (2009). Demanding Respect: The Evolution of the American Comic Book. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-59213-443-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lefèvre, Pascal (2010). "European Comics". In Booker, M. Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels: [Two Volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 185–192. ISBN 978-0-313-35747-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lyga, Allyson A.W.; Lyga, Barry (2004). Graphic Novels in Your Media Center: A Definitive Guide. Libraries Unlimited. ISBN 978-1-59158-142-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- MacWilliams, Mark Wheeler (2008). Japanese Visual Culture: Explorations in the World of Manga and Anime. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-1602-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mansfield, Stephen (2009). Tokyo: A Cultural History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-538634-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCloud, Scott (1993). Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. Kitchen Sink Press. ISBN 978-0-87816-243-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCloud, Scott (2000). Reinventing Comics: How Imagination and Technology Are Revolutionizing an Art Form. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-095350-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McKinney, Mark, ed. (2011). History and Politics in French-Language Comics and Graphic Novels. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-761-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Meskin, Aaron; Cook, Roy T., eds. (2012). The Art of Comics: A Philosophical Approach. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-3464-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, Ann (1998). "Comic Strips/Cartoonists". In Hughes, Alex; Reader, Keith (eds.). Encyclopedia of Contemporary French Culture. CRC Press. pp. 116–119. ISBN 978-0-415-13186-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Miller, Ann (2007). Reading Bande Dessinée: Critical Approaches to French-language Comic Strip. Intellect Books. ISBN 978-1-84150-177-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morita, Naoko (2010). "Cultural Recognition of Comics and Comics Studies: Comments on Thierry Groensteen's Keynote Lecture". In Berndt, Jaqueline (ed.). Comics worlds & the world of comics : towards scholarship on a global scale. Global Manga Studies. 1. International Manga Research Center, Kyoto Seika University. pp. 31–39. ISBN 978-4-905187-03-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nordling, Lee (1995). Your Career in the Comics. Andrews McMeel Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8362-0748-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Nale, Robert (2010). "Manga". In Booker, M. Keith (ed.). Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels: [Two Volumes]. ABC-CLIO. pp. 378–387. ISBN 978-0-313-35747-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Orr, Tamra (2008). Manga Artists. Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4042-1854-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Petersen, Robert (2010). Comics, Manga, and Graphic Novels: A History of Graphic Narratives. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-36330-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Poitras, Gilles (2001). Anime Essentials: Every Thing a Fan Needs to Know. Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-880656-53-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Power, Natsu Onoda (2009). God of Comics: Osamu Tezuka and the Creation of Post-World War II Manga. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-478-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Raz, Aviad E. (1999). Riding the Black Ship: Japan and Tokyo Disneyland. Harvard University Asia Center. ISBN 978-0-674-76894-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rhoades, Shirrel (2008). A Complete History of American Comic Books. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-1-4331-0107-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rowland, Barry D. (1990). Herbie and Friends: Cartoons in Wartime. Dundurn Press. ISBN 978-0-920474-52-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sabin, Roger (1993). Adult Comics: An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-04419-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sabin, Roger (2005). "Some Observations on BD in the US". In Forsdick, Charles; Grove, Laurence; McQuillan, Libbie (eds.). The Francophone Bande Dessinée. Rodopi. pp. 175–188. ISBN 978-90-420-1776-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Saraceni, Mario (2003). The Language of Comics. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21422-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schodt, Frederik L. (1996). Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga. Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-880656-23-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Screech, Matthew (2005). Masters of the Ninth Art: Bandes Dessinées and Franco-Belgian Identity. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85323-938-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stewart, Ronald (2014). "Manga as Schism: Kitazawa Rakuten's Resistance to "Old-Fashioned" Japan". In Berndt, Jaqueline; Kümmerling-Meibauer, Bettina (eds.). Manga's Cultural Crossroads. Routledge. pp. 27–49. ISBN 978-1-134-10283-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stringer, Jenny, ed. (1996). "Graphic novel". The Oxford Companion to Twentieth-Century Literature in English. Oxford University Press. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-19-212271-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sugimoto, Yoshio (2010). An Introduction to Japanese Society. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-87956-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Theobald, John (2004). The Media and the Making of History. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-3822-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomas, Evan (2010). "10: Invisible Art, Invisible Planes, Invisible People". In Aldama, Frederick Luis (ed.). Multicultural Comics: From Zap to Blue Beetle. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-73743-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thorne, Amy (2010). "Part Eight: Metacomic/Webcomics". In Weiner, Robert G. (ed.). Graphic Novels and Comics in Libraries and Archives: Essays on Readers, Research, History and Cataloging. McFarland & Company. pp. 209–212. ISBN 978-0-7864-5693-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tondro, Jason (2011). Superheroes of the Round Table: Comics Connections to Medieval and Renaissance Literature. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-8876-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, Jason (2007). Manga: The Complete Guide. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-345-48590-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vessels, Joel E. (2010). Drawing France: French Comics and the Republic. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-444-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Williams, Paul; Lyons, James (2010). The Rise of the American Comics Artist: Creators and Contexts. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-792-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wong, Wendy Siuyi (2002). Hong Kong Comics. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1-56898-269-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Academic journals

- Couch, Chris (December 2000). "The Publication and Formats of Comics, Graphic Novels, and Tankobon". Image & Narrative (1). ISSN 1780-678X. Retrieved 2012-02-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Frahm, Ole (October 2003). "Too much is too much. The never innocent laughter of the Comics". Image & Narrative (7). ISSN 1780-678X. Retrieved 2012-02-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Groensteen, Thierry (Spring 2012). "The Current State of French Comics Theory". Scandinavian Journal of Comic Art. 1 (1): 111–122.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cohen, Martin S. (April 1977). "The Novel in Woodcuts: A Handbook". Journal of Modern Literature. 6 (2): 171–195. JSTOR 3831165.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yuan, Ting (2011). "From Ponyo to 'My Garfield Story': Using Digital Comics as an Alternative Pathway to Literary Composition". Childhood Education. 87 (4).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Web

- Beerbohm, Robert (2003). "The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck Part III". The Search For Töpffer in America. Retrieved 2012-07-23.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harvey, R.C. (2010-12-20). "Defining Comics Again: Another in the Long List of Unnecessarily Complicated Definitions". The Comics Journal. Fantagraphics Books. Archived from the original on 2011-09-14. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- Markstein, Don (2010). "Glossary of Specialized Cartoon-related Words and Phrases Used in Don Markstein's Toonopedia". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on 2009-10-16. Retrieved 2013-02-05.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- McCloud, Scott (2006). Making Comics: Storytelling Secrets of Comics, Manga and Graphic Novels (1st Perennial ed.). ISBN 0060780940.

- McCloud, Scott (2000). Reinventing Comics: How Tmagination and Technology are Revolutionizing an Art Form (1st Perennial ed.). Perennial. ISBN 0060953500.

- Carrier, David (2002). The Aesthetics of Comics. Penn State Press. ISBN 978-0-271-02188-1.

- Cohn, Neil (2013). The Visual Language of Comics: Introduction to the Structure and Cognition of Sequential Images. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4411-8145-9.

- Dowd, Douglas Bevan; Hignite, Todd (2006). Strips, Toons, And Bluesies: Essays in Comics And Culture. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1-56898-621-0.

- Eisner, Will (1995). Graphic Storytelling. Poorhouse Press. ISBN 978-0-9614728-3-2.

- Estren, Mark James (1993). A History of Underground Comics. Ronin Publishing. ISBN 978-0-914171-64-5.

- Groensteen, Thierry (2007) [1999]. The System of Comics. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-925-5.

- Groensteen, Thierry (2014). "Definitions". In Miller, Ann; Beaty, Bart (eds.). The French Comics Theory Reader. Leuven University Press. pp. 93–114. ISBN 978-90-5867-988-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Groth, Gary; Fiore, R., eds. (1988). The New Comics. Berkley Books. ISBN 978-0-425-11366-0.

- Heer, Jeet; Worcester, Kent, eds. (2012). A Comics Studies Reader. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-109-5.

- Horn, Maurice, ed. (1977). The World Encyclopedia of Comics. Avon. ISBN 978-0-87754-323-7.

- Kunzle, David (1973). The Early Comic Strip: Narrative Strips and Picture Stories in the European Broadsheet from c. 1450 to 1825. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05775-3. OCLC 470776042.

- Kunzle, David (1990). History of the Comic Strip: The Nineteenth Century. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01865-5.

- Sabin, Roger (1996). Comics, Comix and Graphic Novels: A History of Comic Art. Phaidon. ISBN 978-0-7148-3993-6.

- Waugh, Coulton (1947). The Comics. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-0-87805-499-2.

- Stein, Daniel; Thon, Jan-Noël, eds. (2015). From Comic Strips to Graphic Novels. Contributions to the Theory and History of Graphic Narrative. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-042656-4.

External links

Academic journals

- The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship

- ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies

- Image [&] Narrative

- International Journal of Comic Art

- Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics

Archives

- Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum

- Michigan State University Comic Art Collection

- Comic Art Collection at the University of Missouri

- Cartoon Art Museum of San Francisco

- Time Archives' Collection of Comics

- "Comics in the National Art Library". Prints & Books. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 2009-11-04. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

Databases