Chelmsley Wood

Chelmsley Wood is a large housing estate and civil parish within the Metropolitan Borough of Solihull, England, with a population of 12,453.[1][2] It is located near Birmingham Airport and the National Exhibition Centre. It lies about eight miles east of Birmingham City Centre and 5 miles to the north of Solihull town centre.

| Chelmsley Wood | |

|---|---|

The Royal Mail Building in the Town Centre | |

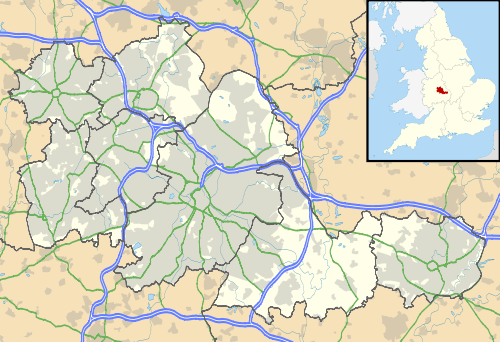

Chelmsley Wood Location within the West Midlands | |

| Population | 12,453 (2011) |

| OS grid reference | SP1886 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Metropolitan borough | |

| Metropolitan county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Birmingham |

| Postcode district | B37 |

| Dialling code | 0121 |

| Police | West Midlands |

| Fire | West Midlands |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

In 1966 Birmingham City Council compulsorily purchased the ancient woodland and built the 15,590 dwelling council estate to rehouse families on its council house waiting list. With the rise in unemployment in the 1970s parts of the estate suffered from deprivation and anti-social behaviour.

Local government re-organisation in 1974 transferred the area to Solihull Metropolitan Borough, though responsibility for the housing remained with Birmingham until September 1980.[2]

The boundaries of Chelmsley Wood have changed since its inception as neighbouring districts have merger and areas within the plan have become independent settlements. The estate itself, now known as North Solihull, is being renovated and extended.

History

Chelmsley Wood is a relatively new area, which was built by Birmingham City Council in the late 1960s and early 70s on ancient woodland, once part of the Forest of Arden, as an overspill town for Birmingham. Permission for the construction of the overspill estate on green belt land was granted by Richard Crossman as Minister of Housing and Local Government.[3] A shopping centre (which opened on 7 April 1970), a library (completed in 1970 at £240,000),[4] hall and belatedly a few public houses. With the adjoining neighbourhoods of Fordbridge and Smith's Wood it became part of Metropolitan Borough of Solihull in 1974.

By the end of the Second World War 12,391 homes had been destroyed by aerial bombing in Birmingham and there was to be no house building in the city for six years[5] so the programme of slum clearance had been halted. By the 1950s there were terrific demand for homes. Large estates were built within the city boundaries such as Druid's Heath, Castle Vale and at Bromford on the site of the city’s former racecourse, but by 1963 there was no further land available within the city boundaries.

The city council had powers under the Housing of the Working Classes Act 1900 to purchase land out-of- area. On 21 December 1964, Richard Crossman the new minister for housing sent a letter to Sir Frank Price, leader of Birmingham City Council proposing the scheme.[6] The population was increasing and it was estimated that there would be a deficiency of 43,000 dwellings by 1971, which would have been worse than it had been in 1959. At a meeting of the House Building Committee in February 1965, it was decided to build a large new development to the east of the city. Objections were raised about the scheme, particularly from Meriden Rural District Council and the local Parish Councils,[5] on grounds of amenity and the threat to the green belt separating Birmingham and Coventry. A similar application for the use of nearly 300 acres at Wythall to the south of Birmingham was considered, but this was turned down. Permission was granted.[5]

"The Wood"

Land was compulsorily purchased and construction of the 15,590 dwellings was begun in 1965 and completed in 1970. Although the area became part of Solihull in 1974, Birmingham City Council retained control of their houses until they were officially transferred to Solihull MBC on 29 September 1980.[5] Construction started in 1965 and the first rates were levied on houses in Oak Croft on 6 March 1967. Such was the scale of the operation that a development company was to design finance and build a complete town centre which was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II on 7 April 1972.[7]

The "Wood" was to be 80% public housing and 18% privately developed homes, houses were reserved for 100 policemen and rows of terraced homes were let out or sold at a reduced rate to key workers: nurses, social workers and teachers working on the estate.[8] The "Wood" had considerable thought put into its planning and won architectural awards for its landscaping.[6] It was provided with schools, a library and shopping areas, but in the early days there was no local pub, the nearest one being reached by a five-mile bus journey.[9]The "unity and harmony"[5] of the design made it appear monotonous rather than modern.

Etymology

The name "Chelmsley" is of considerable antiquity. It indicates a settlement of Saxon origin – the enclosure of Ceolmund. Ceolmund Crescent is the name of the road that passes by the police station, and the Post Office Tower in the town centre. [10] [5] The word "Ceolmund" itself comes from the Old English Ceol "Keel" (of a ship) and Mund "Protection".[11]

Concept and Design

There were the 15,590 dwellings (including 39 multi-storey blocks of flats). There were 70 shop units and 6 major stores, as well as a 4-storey office block and 2 pubs. The 221 dwellings in the town centre included 14 maisonettes over shops.[5] It was laid out in a Radburn style with houses opening out onto pedestrian pathways and open green space, and backing onto the vehicular access.[5] To enhance the openness, there were no fences between gardens and public space.

Tower blocks

With the 6 adjoining estates, which over half a century have merged, there were 51 tower blocks until the late 1990s, in the complex. As of 2015 there are approximately 42 tower blocks left across the estates.

- Chelmsley group - 12 tower blocks

- Richmond House, off Marlene Croft, buil 1967 using the Bison system- 11 storeys

- Trevelyan House, off Marlene Croft, built 1967 using the Bison system - 11 storeys

- Chester Court, aka Hatfield House, off Dunster Rd, built 1967 using the Bison system- 10 storeys

- Warwick Court, aka Bede House, of Dunster Rd, built 1967 using the Bison system- 10 storeys

- Downing House, off Willow Way, built 1967 using the Bison system- 9 storeys

- Darwin House, off Alder Dr, built 1967 using the Bison system- 9 storeys

- Kingsgate House, off Winchester Dr (Area 3), built 1968 by Wimpey- 11 storeys

- Avoncroft House, off Winchester Dr (Area 3), built 1968 by Wimpey- 11 storeys

- Fircroft House, off Winchester Dr (Area 3), built 1968 by Wimpey- 11 storeys

- Woodbrook House, off Hedgetree Croft/ Larch Croft, built 1968 using the Bison system- 13 storeys

- Dillington House, off Moorend Av/ Town Centre, built 1968 using the Bison system - 10 storeys

- Chestnut House, off Moorend Av/ Town Centre, built 1968

Transport

National Express West Midlands operate a number of buses in and around the Chelmsley Wood area. Chelmsley Wood shopping centre has a bus interchange which hosts buses that go to and from Birmingham city centre, Solihull town centre, Coleshill, Warwickshire, Sutton Coldfield and Birmingham Airport. In Summer 2017, National Express West Midlands extensively rerouted and retimed all of their bus routes that run to/from Chelmsley Wood.

The closest railway station is at Marston Green which is about a mile (1.75 km) from Chelmsley Wood Shopping Centre. From there, there are trains to Coventry, Birmingham Airport, Birmingham City Centre and The National Exhibition Centre.

Leisure

North Solihull Sports Centre is the largest and most used sports centre in Chelmsley Wood and its surrounding areas. It hosts two swimming pools, a sports hall, a fitness suite, studio, crèche and café bar. It also hosts an outdoor running track, and an astroturf pitch.[12]

Recent development

The area has for decades had a negative reputation due to being associated with anti-social behaviour and crime,[13] although the estate has been relatively successful compared to other similar estates across England.

The area is currently undergoing the biggest redevelopment project in its history.[14] So far, a new large supermarket and a new library have been built, new schools have been built, many of the most run down properties have been demolished, especially in the Craig Croft area, a new village centre is under construction and all of the remaining tower blocks have been reclad.

Demographics

Politically, Chelmsley Wood is represented by three councillors on Solihull Council. Voters had historically been known for their strong support of Labour candidates at both local and national elections. However, in the 2006 election, the Chelmsley Wood ward elected a candidate from the British National Party, the first in Solihull's history. The elected candidate won by a margin of 19 votes. In the 2010 election the seat went back to Labour after George Morgan stood down with the BNP vote falling dramatically and the Green Party finishing second to Labour by 22 votes.[15]

Since 2011, Chelmsley Wood residents have elected Green Party councillors to serve them at every election, voting in Karl Macnaughton (2011), Chris Williams (2012) and James Burn (2014). Karl Macnaughton was re-elected in the 2015 elections with over 68% of the vote, and Chris Williams in 2016 with 75%.

References

- "2013 Ward Profile : Chelmsley Wood" (PDF). Solihull Observatory. Spring 2013. p. 4. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- Parish Websites Ltd. "Chelmsley Wood Then and Now | Chelmsley Wood Town Council in West Midlands". chelmsleywood-tc.gov.uk. www.parishcouncil.net. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- Stephen Victor Ward (1994). Planning and Urban Change. Sage Publications. ISBN 1-85396-218-X.

- Thomas Greenwood (1971). The Libraries, Museums and Art Galleries Year Book. New York: J. Clarke.

- "History of Chelmsley Wood". Metropolitan Borough of Solihull. Retrieved 14 January 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanley 2012, p. 29.

- "Chelmsley Wood Nostalgia". Birmingham Mail. 2 July 2014. Retrieved 14 July 2018.

- Hanley 2012, pp. 33,34,43.

- Hanley 2012, p. 31.

- "Around Chelmsley in times past". abebooks.co.uk.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Meaning of Ceolmund". Behind The Name. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- "North Solihull Sports Centre". leisurecentre.com. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 18 January 2013.

- Hannah Jennings Parry (22 October 2014). "People Like Us: Chelmsley Wood residents braced for backlash over BBC3 show". Birmingham Mail.

- "Housing Developments". Investing in North Solihull. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- "Local Election Results 2010". Solihull Council. Archived from the original on 10 May 2010. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

Further reading

- Hanley, Lynsey (2012). Estates : an intimate history. Granta. ISBN 9781847087027.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)