Park Hill, Sheffield

Park Hill is a council housing estate in Sheffield, South Yorkshire, England. It was built between 1957 and 1961, and in 1998 was given Grade II* listed building status.[1] Following a period of perceived decline, the estate is being renovated by developers Urban Splash into a mostly private mixed-tenure estate made up of homes for market rent, private sale, shared ownership, and student housing while around a quarter of the units in the development will be social housing.[2][3][4] The renovation was one of the six short-listed projects for the 2013 RIBA Stirling Prize. The Estate falls within the Manor Castle ward of the City. Park Hill is also the name of the area in which the flats are sited. The name relates to the deer park attached to Sheffield Manor, the remnant of which is now known as Norfolk Park.

| Park Hill Flats | |

|---|---|

| General information | |

| Location | Sheffield |

| Coordinates | 53.380°N 1.458°W |

| Status | Under renovation |

| Area | 400 acres (160 ha) |

| No. of flats | 995 |

| Density | People 192 per acre (470/ha) |

| Construction | |

| Constructed | 1957–1961 |

| Architect | Jack Lynn Ivor Smith under J L Womersley |

| Contractors | Direct service organisation |

| Authority | Sheffield City Council |

| Style | Brutalism |

| Influence | Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation and the Smithsons' |

| Refurbishment | |

| Proposed action | Strip to H frame and rebuild |

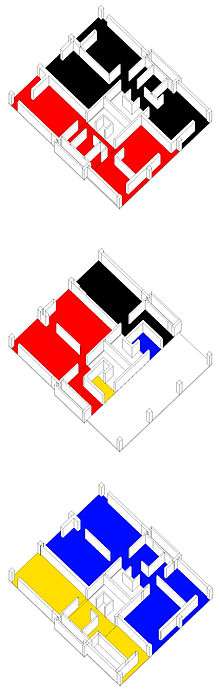

| Units | 257 flats for sale, 56 flats for rent, 12 flats for shared ownership, a new GPs’ surgery, a nursery, retail and leisure facilities. |

| Refurbished | 2006–2022 |

| Architect | Studio Egret West, Hawkins Brown and Grant Associates |

| Contractor | Urban Splash |

| Directing authority | Sheffield City Council |

| Listing | |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Designated | 1998 |

| Reference no. | 1246881 |

As part of phase two of the Park Hill regeneration, part of the structure is planned to reopen as student accommodation in September 2020 under the name Béton House.

History

Park Hill was previously the site of back-to-back housing, a mixture of 2–3-storey tenement buildings, waste ground, quarries and steep alleyways.[5] The streets were arranged in a gridiron with continuous terraces of back-to-back houses facing the streets, backing onto other houses facing into an internal court-yard. There were shared privies that were not connected to mains drainage. One standpipe supported up to 100 people.[5] It was colloquially known as "Little Chicago" in the 1930s, due to the incidence of violent crime there.[6] Clearance of the area began during the 1930s. The first clearance was made for the Duke/Bard/Bernard Street scheme in 1933. The courts were replaced with four storey blocks of maisonettes. In 1935 it was proposed to clear the central area which included streets to the south of Duke Street; South Street, Low Street, Hague Lane, Lord Street, Stafford Street, Long Henry Street, Colliers Row, Norwich Street, Gilbert Street and Anson Street. John Rennie, the city’s Medical Officer of Health, concluded:

- "...the dwelling houses in that area [of Duke Street, Duke Street Lane, South Street and Low Street] are by reason of disrepair or sanitary defects unfit for human habitation, or are by reason of their bad arrangement, or the narrowness or bad arrangement of the streets, dangerous or injurious to the health of the inhabitants of the area, and that the other buildings in the area are for a like reason dangerous or injurious to the health of the said inhabitants, and that the most satisfactory method of dealing with the conditions in the area is the demolition of all the buildings in the area."[7]

G. C. Craven, the city's Planning officer recommended wholesale demolition and possible replacement with multi-storey flats. The Second World War halted this.[8]

Following the war it was decided that a radical scheme needed to be introduced to deal with rehousing the Park Hill community. To that end, architects Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith under the supervision of J. L. Womersley, Sheffield Council's City Architect, began work in 1953 designing the Park Hill Flats. Inspired by Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation and the Smithsons' unbuilt schemes, most notably for Golden Lane in London, the deck access scheme was viewed as revolutionary at the time.[9] The style is known as brutalism.[10]

Construction

Construction began in 1957. Park Hill (Part One) was officially opened by Hugh Gaitskell, MP and Leader of the Opposition, on 16 June 1961.[11] The City Council published a brochure on the scheme which was in several languages, including Russian.

To maintain a strong sense of community, neighbours were re-homed next door to each other and old street names from the area were re-used (e.g. Gilbert Row, Long Henry Row).[12] Cobbles from the terraced streets surrounded the flats and paved the pathways down the hill to Sheffield station and tramlines.[12]

The second phase consisted of a 4 high rise blocks, containing 1160 dwellings, on the hill behind, joined to the main scheme by two three-storey terraces to the east of Bernard Street that contained 153 dwellings. This was renamed in May 1961, becoming the Hyde Park flats. The terraces became Hyde Park Walk and Hyde Park Terrace. The Hyde Park tower blocks were between five and 19 storeys high. This was opened on 23 June 1966 by Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother.[13]

Further housing schemes were completed to similar designs, including the Broomhall and Kelvin developments in Sheffield. They were initially popular and successful. Government restrictions on how potential tenants were allocated to flats and the limitations of the fabric of the building which decayed when not adequately maintained, poor noise insulation and resident security caused their popularity to wane.[14] For many years, the council found it difficult to find tenants for the flats.

Listing and renovation

Despite the problems, the complex remained structurally sound,[15] unlike many system-built blocks of the era, and controversially was Grade II* listed in 1998 making it the largest listed building in Europe.[1] Sheffield City Council hoped this would attract investment to renovate the building, but this was not initially forthcoming. The decision to list the estate was controversial at the time and it continues to attract criticism.[16] A part-privatisation scheme by the developer Urban Splash in partnership with English Heritage to turn the flats into upmarket apartments, business units and social housing is now underway.[16][17] Two blocks (including the North Block, the tallest part of the buildings) were initially cleared, leaving only their concrete shell. The renovation was one of the six shortlisted projects for the 2013 RIBA Stirling Prize.[15] The renovation was due to start in around 2007 but was put on hold due to the recession. Work started in 2009 with the first phase open to residents in 2010/11. After setbacks, in October 2016 it was announced that the full renovation would be ready in 2022.

Sheffield City Council have created a new public park, South Street Open Space, between the railway station and Park Hill. This includes a series of seating terraces and new planting areas.

Description

Background

The Park Hill area of Sheffield contained and had a population density in the range of 100 to 400 per acre (250 to 990/ha). It was identified as a slum where, according to Patrick Abercrombie's Sheffield Civic Survey and Development Plan (1924), there were death rates in the lower Park district of 20–26 per 1,000 inhabitants, and infant (under one year) mortality rate of 153–179 per 1,000 births. The central area amounted to 710 acres (290 ha), and contained 140 designated clearance areas.[1]

Design

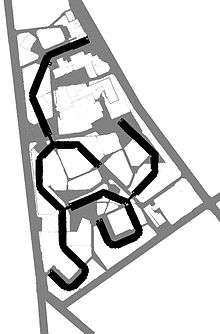

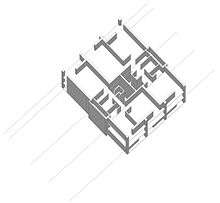

The 995 Park Hill flats and maisonettes, 3 pubs and 31 shops were built in 4 ranges linked by bridges across the upper decks. The ranges were canted at obtuse angles to maximise the panoramic views across the city and the southern Pennines. The stair columns and lifts were placed at each turn. There were two service lifts capable of elevating maintenance vehicles.[18]

The site is steeply sloping (gradient 1 in 10), enabling the designers to maintain a constant roof level though the buildings ranged from 4 to 13 storeys. There were access roadways 10 feet (3.0 m) on every third storey; these serviced a one-storey flat beneath and a 2-storey maisonette on that level and on the level above. The horizontal design repeated itself every three bays, centred on a H-frame that carried the services and stair columns. Each of these units contained a one-bedroom flat, a two-bedroom flat, a two-bedroom maisonette and a three-bedroom maisonette, and stair columns. The kitchens and bathrooms were vertically aligned, allowing simple ducting for services and the Garchey waste disposal system.[18]

Construction is of an exposed concrete frame with a progression of purple, terracotta, light red and cream brick curtain walling.[18] However, as a result of weathering and soot-staining from passing trains, few people realise this and assume the building to be constructed entirely from concrete.

The concept of the flats was described as streets in the sky. There were four street decks, wide enough for milk floats, had large numbers of front doors opening onto them. This was a key concept of the design. Each deck of the structure, except the top one, has direct access to ground level at some point on the sloping site.[18]

The shopping facilities, known as The Pavement were provided on the lowest part of the site, there were four public houses (pubs): The Earl George on The Pavement, The Link and the Scottish Queen on Gilbert Row, and the Parkway on Hague Row.[18]

Location

Park Hill is one of the seven hills on which Sheffield is built. It is south of the River Don, and to the east of the River Sheaf. The estate is on steeply rising land the lower slopes, it is upwind of the former heavily polluting industrial areas of the Don Valley. The estate is bounded by Park Square roundabout on the A61, the B6070 Duke Street, B6071 Talbot Street and South Street.

Immediately to the west is Sheffield railway station that in 2010–11, was the 35th-busiest in the UK, and the 11th-busiest outside London.[19]

Arts

A piece of graffiti, "Clare Middleton I love you will u marry me", which is written on one of the "bridges" linking two of the blocks, was the subject of a documentary broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 2011. The presenter went in search of the story behind the graffiti,[20] eventually finding that Clare did not marry the author of the graffiti, a man named Jason. She died of cancer in 2007. As part of the refurbishment of the estate the developers have chosen to illuminate the portion of the graffiti reading "I love you will u marry me" in neon. Clare Middleton's name has not been illuminated.[21]

Even now, inhabitants of Sheffield are split on the matter of Park Hill; many believe it to be a part of Sheffield's heritage, while others consider it an eyesore and blot on the landscape.[22] Public nominations led it to the top 12 of Channel 4's Demolition programme. Other television appearances for the flats include Police 2020 and in an Arctic Monkeys video. A BBC programme called Saving Britain's Past sheds light on the building site's past and discusses the listing from several viewpoints in its second episode, called "Streets in the Sky". The 2014 film '71 used the buildings to recreate Belfast's notorious Divis Flats during The Troubles.

Park Hill has featured as a major source of inspiration for British artist Mandy Payne, with her paintings of the estate winning several awards.

Park Hill is referenced in the lyrics of Pulp's song "Sheffield Sex City".

Park Hill appears on the cover of Eagulls' self-titled debut album.

The building was used as the location for Harvey and Gadget's flat in This Is England 90.

The area and above-mentioned graffiti are the subject of the song "I Love You, Will You Marry Me" by South Yorkshire-born musician Yungblud.

Park Hill is featured in the eleventh series and twelfth series of Doctor Who,[23] as the family home of companion Yasmin Khan.

The musical Standing at the Sky's Edge, featuring songs by Richard Hawley, is set in Park Hill and tells the story of three families over sixty years begging in 1961. The musical premiered at the Crucible Theatre, Sheffield in 2019.

Photo gallery

- Welcome sign and plan at the main entrance.

Entrance of Park Hill

Entrance of Park Hill Panorama of Park Hill

Panorama of Park Hill One of the Park Hill facades

One of the Park Hill facades- Close-up of the exterior

See also

- List of brutalist apartment blocks in Sheffield

- Cables Wynd House, Edinburgh, Scotland

- Byker Wall, Newcastle upon Tyne, England

- Prora, Rügen, Germany

- Falowiec, Gdansk, Poland

- Karl-Marx-Hof, Vienna, Austria

- Spinaceto, Rome, Italy

- Ballymun Flats, Dublin, Ireland

- Golden Lane Estate competition entry by Alison and Peter Smithson, London

- Robin Hood Gardens, London

- Habitat 67, Canada

References

- Notes

- Sheffield Sources 2010.

- Local Government Yorkshire and Humber "Park Hill" Retrieved 10 March 2011

- BBC. "Park Hill's future". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Hopkirk2018-07-31T11:11:00+01:00, Elizabeth. "Local firm cleared for Park Hill student housing". Building. Retrieved 9 December 2019.

- Sheffield Sources 2010, p. 14.

- Milner, Will. "Gangs: A history of violence". Now Then Magazine. Opus Independents. Retrieved 2 April 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheffield Archives: CA-MIN/74,p. 221

- Sheffield Sources 2010, p. 9.

- Sheffield Sources 2010, p. 16.

- Meades, Jonathan (13 February 2014). "The incredible hulks: Jonathan Meades' A-Z of brutalism". Guardian. Guardian Newspapers. Retrieved 2 April 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheffield Sources 2010, p. 22.

- "Park Hill's History". BBC. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- Sheffield Sources 2010, p. 20.

- "Places: Park Hill". Sheffield and South Yorkshire. BBC. 24 September 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Townsend, Lucy (16 September 2013). "Stirling Prize:Park Hill Phase 1". BBC New Magazine. BBC. Retrieved 2 April 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "The absurd listing of a block of flats in Sheffield is richly comic". Guardian. London. 19 April 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- Moore, Rowan (21 August 2011). "Park Hill estate, Sheffield – review". Observer. Guardian Newspapers. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- Listing & 1246881.

- "Station Usage 2010-2011". Rail statistics. Office of Road and Rail. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- Elisabeth Mahoney (7 August 2011). "Radio review: The I Love You Bridge". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- "Truth of Sheffield's 'I Love You Will U Marry Me' graffiti". BBC News. 8 August 2011. Retrieved 13 August 2011.

- Haines, Samantha (19 July 2013). "Sheffield's Park Hill flats: Design icon or concrete eyesore?". BBC News. Retrieved 1 November 2014.

- "Doctor Who premiere: How Sheffield red carpet happened". BBC News. Retrieved 25 September 2018.

- Bibliography

- Sources for the study of the history of Park Hill flats (PDF). Sheffield: Sheffield City Council's Libraries and Archives. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Historic England. "Park Hill (1246881)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Park Hill. |

- Exploring Park Hill Flats Collection of sources and essays collected by Urban Splash.

- Several photos of Park Hill housing by Peter Jones

- Sheffield's Park Hill: Estate expectations, Stephen Kelly, The Independent, 2011

- Park Hill Housing Project (1962), Yorkshire Film Archive (film)

- "Governmentality on the Park Hill Estate: The rationality of public housing, Urban Studies 37 (2010)". (Pay wall)

- "Open 2 - From Here to Modernity - Park Hill". (web site moving)

- Pidd, Helen (20 July 2018). "Streets in the sky … the Sheffield high-rises that were home sweet home". the Guardian. Bill Stevensons photo exhibition