Caspian tiger

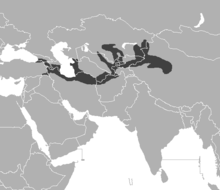

The Caspian tiger was a tiger from a specific population of the Panthera tigris tigris subspecies that was native to the eastern Turkey, northern Iran, Mesopotamia, the Caucasus around the Caspian Sea through Central Asia to northern Afghanistan and Xinjiang in western China.[5] It inhabited sparse forests and riverine corridors in this region until the 1970s.[1] This population was assessed as extinct in 2003.[2]

| Caspian tiger | |

|---|---|

| |

| Tiger from the Caucasus in Berlin Zoo, 1899[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | †P. t. tigris |

| Trinomial name | |

| Panthera tigris tigris | |

| |

| Original distribution of the Caspian tiger (in black) | |

| Synonyms[3][4] | |

| |

Felis virgata was the scientific name proposed in 1815 by Johann Karl Wilhelm Illiger for tigers in the Caspian Sea area.[6] It was traditionally recognised as a distinct subspecies, Panthera tigris virgata. However, results of phylogeographic analysis indicate that the Caspian and Siberian tiger populations shared a common continuous geographic distribution until the early 19th century.[7]

Some Caspian tiger individuals were intermediate in size between Siberian and Bengal tigers.[8][3][9]

The Caspian tiger was also called Balkhash tiger, Hyrcanian tiger, Turanian tiger,[2] and Babre Mazandaran (Persian: ببرِ مازندران), depending on the region of its occurrence.[10]

Taxonomy

Felis virgata was the scientific name used by Illiger in 1815 when he described the greyish tigers in the area of the Caspian Sea and Persia.[6] In 1929, Reginald Innes Pocock subordinated the tiger to the genus Panthera.[11] For several decades, the Caspian tiger was considered a distinct tiger subspecies.[3][4]

In 1999, the validity of several tiger subspecies was questioned. Most putative subspecies described in the 19th and 20th centuries were distinguished on basis of fur length and colouration, striping patterns and body size, hence characteristics that vary widely within populations. Morphologically, tigers from different regions vary little, and gene flow between populations in those regions is considered to have been possible during the Pleistocene. Therefore, it was proposed to recognize only two tiger subspecies as valid, namely P. t. tigris in mainland Asia, and P. t. sondaica in the Greater Sunda Islands and possibly in Sundaland.[12]

At the start of the 21st century, genetic studies were carried out using 20 tiger bone and tissue samples from museum collections and sequencing at least one segment of five mitochondrial genes. Results revealed a low amount of variability in the mitochondrial DNA in Caspian tigers; and that Caspian and Siberian tigers were remarkably similar, indicating that the Siberian tiger is the genetically closest living relative of the Caspian tiger. Phylogeographic analysis indicates that the common ancestor of Caspian and Siberian tigers colonized Central Asia via the Gansu−Silk Road region from eastern China less than 10,000 years ago, and subsequently traversed eastward to establish the Siberian tiger population in the Russian Far East. The Caspian and Siberian tigers were likely a single contiguous population until the early 19th century, but became isolated from another due to fragmentation and loss of habitat during the Industrial Revolution.[7]

In 2015, morphological, ecological and molecular traits of all putative tiger subspecies were analysed in a combined approach. Results support distinction of the two evolutionary groups continental and Sunda tigers. The authors proposed recognition of only two subspecies, namely P. t. tigris comprising the Bengal, Malayan, Indochinese, South Chinese, Siberian and Caspian tiger populations, and P. t. sondaica comprising the Javan, Bali and Sumatran tiger populations. Tigers in mainland Asia fall into two clades, namely a northern clade formed by the Caspian and Siberian tiger populations, and a southern clade formed by populations in remaining mainland Asia.[13]

In 2017, the Cat Specialist Group revised felid taxonomy and now recognizes the tiger populations in continental Asia as P. t. tigris.[5] However, a genetic study published in 2018 supported six monophyletic clades, with the Amur and Caspian tigers being distinct from other mainland Asian populations, thus supporting the traditional concept of six living subspecies.[14]

Characteristics

Fur

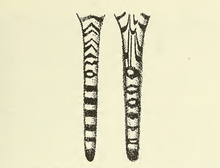

Photographs of skins of Caspian and Amur tigers indicate that the main background colour of the Caspian tiger's fur varied and was generally brighter and more uniform than that of the Siberian tiger. The stripes were narrower, fuller and more closely set than those of tigers from Manchuria. The colour of its stripes was a mixture of brown or cinnamon shades. Pure black patterns were invariably found only on head, neck, the middle of the back and at the tip of the tail. Angular patterns at the base of the tail were less developed than those of Far Eastern populations. The contrast between the summer and winter coats was sharp, though not to the same extent as in Far Eastern populations. The winter coat was paler, with less distinct patterns. The summer coat had a similar density and hair length to that of the Bengal tiger, though its stripes were usually narrower, longer and closer set. It had the thickest fur amongst tigers, possibly due its occurrence in the temperate parts of Eurasia.[8][3][9]

Size

The Caspian tiger ranked among the largest cats that ever existed.[3][8][15] Males had a body length of 270–295 cm (106–116 in) and weighed 170–240 kg (370–530 lb); females measured 240–260 cm (94–102 in) in head-to-body and weighed 85–135 kg (187–298 lb).[3] Maximum skull length in males was 297–365.8 mm (11.69–14.40 in), while that of females was 195.7–255.5 mm (7.70–10.06 in).[8] Its occiput was broader than of the Bengal tiger.[12]

Some individuals attained exceptional sizes. In 1954, a tiger was killed near the Sumbar River in Kopet-Dag whose stuffed skin was put on display in a museum in Ashgabat. Its head-to-body length was 2.25 m (7.4 ft). Its skull had a condylobasal length of about 305 mm (12.0 in), and zygomatic width of 205 mm (8.1 in). Its skull length was 385 mm (15.2 in), hence more than the known maximum of 365.8 mm (14.40 in) for this population, and slightly exceeding skull length of most Siberian tigers.[8] In Prishibinske, a tiger was killed in February 1899. Measurements after skinning revealed a body length of 270 cm (8.9 ft) between the pegs, plus a 90 cm (3.0 ft) long tail, giving it a total length of about 360 cm (11.8 ft). Measurements between the pegs of up to 2.95 m (9.7 ft) is known.[3] According to Satunin it was "a tiger of immense proportions" and "no smaller than the common Tuzemna horse." It had rather long fur.[8]

Skull size and shape of Caspian tigers significantly overlap with and are almost indistinguishable from other tiger specimens in mainland Asia.[16]

Distribution and habitat

Historical records show that the distribution of the tiger in the region of the Caspian Sea was not continuous but patchy, and associated with wetlands such as river basins, lake edges and sea shores.[8] In the 19th century, tigers occurred in:

- the Eastern Anatolia Region, which is considered to have been the westernmost area where tigers occurred.[1] Records are known from the region of Mount Ararat, Şanlıurfa, Şırnak, Siirt and Hakkari Provinces in eastern Turkey; in the Hakkari Province tigers possibly occurred up to the 1990s.[17][18] The only confirmed record in Iraq dates to 1887 when a tiger was shot near Mosul, which is considered to have been a migrant from southeastern Turkey.[17] There are also claims of historical tiger presence in the area of the Tigris–Euphrates river system in Iraq and Syria.[19][20]

- the extreme southeast of the Caucasus, such as in hilly and lowland forests of the Talysh Mountains, in the Lenkoran Lowlands, in the lowland forests of Prishib, from where tigers moved into the eastern plains of the Trans-Caucasus up to the Don River basin; the Arasbaran and Zangezur Mountains of northwestern Persia.[8] In Iran, historical records are known only from along the southern coast of the Caspian Sea and adjacent Alborz Mountains.[21]

- Central Asia such as southwestern Turkmenia along the Atrek River and its tributaries, Sumbar and Chandyr Rivers; in the western and southwestern parts of Kopet-Dag; in the environs of Ashkabad in the northern foothills; in Afghanistan along the upper reaches of Hari-Rud at Herat, and along the jungles in the lower reaches of the river; around Tedzhen and Murgap and along the Kushka and Kashan rivers; in the Amu-Darya basin as far the Aral Sea and along the entire coast of the Aral Sea; along the Syr-Darya to the Fergana Valley as far as Tashkent and the western spur of Talas Alatau; along the Chu and Ili Rivers; all along the southern shore of Lake Balkhash and northwards into the southern Altai Mountains, and to southeastern Transbaikal or Western Siberia in the east.[8][22] In China, it occurred in the Tarim, Manasi River and Lop Nur basins.[1]

Its former distribution can be approximated by examining the distribution of ungulates in the region.[23] Wild boar was the numerically dominant ungulate occurring in forested habitats, along watercourses, in reed beds and in thickets of the Caspian and Aral Seas. Where watercourses penetrated deep into desert areas, suitable wild pig and tiger habitat was often linear, only a few kilometers wide at most. Red and roe deer occurred in forests around the Black Sea to the western side and around the southern side of the Caspian Sea in a narrow belt of forest cover. Roe deer occurred in forested areas south of Lake Balkash. Bactrian deer occurred in the narrow belt of forest habitat on the southern border of the Aral Sea, and southward along the Syr-Darya and Amu-Darya rivers.[8]

Local extinction

The demise of the Caspian tiger began with the Russian colonisation of Turkestan during the late 19th century.[24] Its extirpation was caused by several factors:

- Tigers were killed by large parties of sportsmen and military personnel who also hunted tiger prey species such as wild pigs. The range of wild pigs underwent a rapid decline between the middle of the 19th century and the 1930s due to overhunting, natural disasters, and diseases such as swine fever and foot-and-mouth disease, which caused large and rapid die-offs.[8]

- The extensive reedbeds of tiger habitat were increasingly converted to cropland for planting cotton and other crops that grew well in the rich silt along rivers.[24]

- Tigers were already vulnerable due to the restricted nature of their distribution, having been confined to watercourses within the large expanses of desert environment.[23]

Until the early 20th century, the regular Russian army was used to clear predators from forests, around settlements, and potential agricultural lands. Until World War I, about 100 tigers were killed in the forests of Amu-Darya and Piandj Rivers each year. High incentives were paid for tiger skins up to 1929. The prey base of tigers, wild pigs and deer, were decimated by deforestation and subsistence hunting by the increasing human population along the rivers, supported by growing agricultural developments.[25] By 1910, cotton plants were estimated to occupy nearly one-fifth of Turkestan's arable land, with about one half located in the Fergana Valley.[26]

Last sightings

In Iraq, a tiger was killed near Mosul in 1887.[1][17]

In Georgia, the last known tiger was killed in 1922 near Tbilisi, after taking domestic livestock.[1][27] Its stuffed body was put on display in the Georgian National Museum.[28][29]

In China, tigers disappeared from the Tarim River basin in Xinjiang in the 1920s.[1][27] From the Manasi River basin in the Tian Shan Range west of Ürümqi they reportedly disappeared in the 1960s.[8]

In Turkey, a pair of tigers was allegedly killed in the area of Selçuk in 1943.[30] Several tiger skins found in the early 1970s near Uludere indicated the presence of a tiger population in eastern Turkey.[31][32] Questionnaire surveys conducted in this region revealed that one to eight tigers were killed each year until the mid-1980s, and that tigers likely had survived in the region until the early 1990s. Due to lack of interest, in addition to security and safety reasons, no further field surveys were carried out in the area.[18]

In Kazakhstan, the last Caspian tiger was recorded in 1948, in the environs of the Ili River, the last known stronghold in the region of Lake Balkhash.[8]

In Iran, one of the last known tigers was shot in Golestan National Park in 1953. Another individual was sighted in the Golestan area in 1958.[9]

In Turkmenistan, the last known tiger was killed in January 1954 in the Sumbar River valley in the Kopet-Dag Range.[33] The last record from the lower reaches of the Amu-Darya river was an unconfirmed observation in 1968 near Nukus in the Aral Sea area. By the early 1970s, tigers disappeared from the river's lower reaches and the Pyzandh Valley in the Turkmen-Uzbek-Afghan border region.[8]

The Piandj River area between Afghanistan and Tajikistan was a stronghold of the Caspian tiger until the late 1960s. The latest sighting of a tiger in the Afghan-Tajik border area dates to 1998 in the Babatag Range.[25]

Behaviour and ecology

No information is available for home ranges of Caspian tigers. In search for prey, they possibly prowled widely and followed migratory ungulates from one pasture to another. Wild pigs and cervids probably formed their main prey base. In many regions of Central Asia, Bactrian deer and roe deer were important prey species, as well as Caucasian red deer, goitered gazelle in Iran; Eurasian golden jackals, jungle cats, locusts, and other small mammals in the lower Amu-Darya River area; saiga, wild horses, Persian onagers in Miankaleh peninsula; Turkmenian kulans, Mongolian wild asses, and mountain sheep in the Zhana-Darya and around the Aral Sea; Manchurian wapiti and moose in the area of Lake Baikal. They caught fish in flooded areas and irrigation channels. In winter, they frequently attacked dogs and livestock straying away from herds. They preferred drinking water from rivers, and drank from lakes in seasons when water was less brackish.[8]

Sympatric carnivores

Species that were sympatric with the Caspian tiger include:

- The Persian leopard was most likely distributed over the whole Caucasus;[35] today, it survives only in small and fragmented populations in this region.[36]

- The jungle cat was recorded in wetlands bordering the Caspian Sea, in the Volga River delta and in valleys of the Terek, Kura, Aras, Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers;[37][38] in southern Turkey it is known from a few coastal and inland wetlands.[39]

- The Asiatic wildcat occurs from south-eastern Turkey, Kurdistan and the Caucasus across Central Asia to India and Mongolia in a variety of habitats.[40]

Disease

Two tigers in southwestern Tajikistan harbored 5–7 tapeworms (Taenia bubesei) in their small and large intestines.[8]

Conservation efforts

Soviet Union

In 1938, the first protected area Tigrovaya Balka (Russian: Тигровая балка, lit. 'Tiger dry creek or Tiger arroyo'), was established in Tajikistan. The name was given to this zapovednik after a tiger had attacked two Russian Army officers riding horseback along dried-up river channel known in Russian as balka. Tigrovaya Balka was apparently the last refuge of Caspian tigers in the Soviet Union, and is situated in the lower reaches of Vakhsh River between the Piandj and Kofarnihon Rivers near the border of Afghanistan. A tiger was seen there in 1958.[41]

After 1947, tigers were legally protected in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.[25]

Iran

In Iran, Caspian tigers had been protected since 1957, with heavy fines for shooting. In the early 1970s, biologists from the Department of Environment searched several years for Caspian tigers in the uninhabited areas of Caspian forests, but did not find any evidence of their presence.[9]

Central Asian reintroduction

Stimulated by recent findings that the Siberian tiger (Amur population) is the closest relative of the Caspian tiger, albeit slightly bigger than it, discussions started as to whether the Amur tiger could be an appropriate subspecies for reintroduction into a safe place in Central Asia.[42] The Amu-Darya Delta was suggested as a potential site for such a project. A feasibility study was initiated to investigate if the area is suitable and if such an initiative would receive support from relevant decision makers. A viable tiger population of about 100 animals would require at least 5,000 km2 (1,900 sq mi) of large tracts of contiguous habitat with rich prey populations. Such habitat is not available at this stage and cannot be provided in the short term. The proposed region is therefore unsuitable for the reintroduction, at least at this stage.[25]

While the restoration of the Caspian tiger has stimulated discussions, the locations for the tiger have yet to become fully involved in the planning. But through preliminary ecological surveys it has been revealed that some small populated areas of Central Asia have preserved natural habitat suitable for tigers.[43]

In captivity

Three tigers from Mazandaran were part of a collection of animals that the Persian Qajari Shah Naser al-Din used to found Tehran Zoological Garden in the 19th century.[44] A tiger from the Caucasus was housed at Berlin Zoo in the same century.[1] DNA from a tiger caught in northern Iran and housed at Moscow Zoo in the 20th century was used in the genetic test that established the Caspian tiger's close relationship with the Siberian tiger.[7]

In culture

- During the Roman Empire, tigers and other large mammals were used in combats during gladiatorial games.[45]

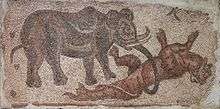

- The babr (Persian: ببر, tiger) features in Persian and Central Asian culture. The name "Babr Mazandaran" is sometimes given to a prominent wrestler.[10] The Persian people are apparently represented by the tiger in a Syrian mosaic from Palmyra, which commemorates the victory of Palmyrene King Odaenathus over them. The inscription conceals an earlier one that read: (Mrn), which is a title used by Odaenathus.[46] It has been suggested that it celebrates Odaenathus' victory over the Persians, the archer representing Odaenathus and the tigers the Persians; Odaenathus is about to be crowned with victory by the eagle flying above him.[47]

- In the Fables of Pilpay, the tiger is described as furious and avid to rule over wilderness.[48]

- In the Taurus Mountains, stone traps were used to capture leopards and tigers.[49]

Gallery

A mosaic from Palmyra named the "tiger mosaic".

A mosaic from Palmyra named the "tiger mosaic".- Statues of a man and a tiger, on the way to Mount Akhun, North Caucasus, 2013

A tigress and cub featured on a postage stamp from Azerbaijan, South Caucasus, 1997

A tigress and cub featured on a postage stamp from Azerbaijan, South Caucasus, 1997 Painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme, commissioned by William Thompson Walters in 1863 shows persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire, using the tiger (bottom left) and lion.

Painting by Jean-Léon Gérôme, commissioned by William Thompson Walters in 1863 shows persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire, using the tiger (bottom left) and lion.

See also

- Tiger populations: Bengal tiger · Siberian tiger · Caspian tiger · Sumatran tiger · South Chinese tiger · Indochinese tiger · Bali tiger · Javan tiger

- Prehistoric tigers: Panthera tigris soloensis · Panthera tigris trinilensis · Panthera tigris acutidens

References

- Nowell, K.; Jackson, P. (1996). "Caspian tiger Panthera tigris virgata". Wild Cats: status survey and conservation action plan (PDF). IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group, Gland, Switzerland. Archived from the original on 2007-08-24.

- Jackson, P.; Nowell, K. (2011). "Panthera tigris ssp. virgata". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2011: e.T41505A10480967. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T41505A10480967.en.

- Mazák, V. (1981). "Panthera tigris" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 152 (152): 1–8. doi:10.2307/3504004. JSTOR 3504004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-09.

- Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 548. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Kitchener, A. C.; Breitenmoser-Würsten, C.; Eizirik, E.; Gentry, A.; Werdelin, L.; Wilting, A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Abramov, A. V.; Christiansen, P.; Driscoll, C.; Duckworth, J. W.; Johnson, W.; Luo, S.-J.; Meijaard, E.; O'Donoghue, P.; Sanderson, J.; Seymour, K.; Bruford, M.; Groves, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Nowell, K.; Timmons, Z.; Tobe, S. (2017). "A revised taxonomy of the Felidae: The final report of the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN Cat Specialist Group" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 11): 66–68.

- Illiger, C. (1815). "Überblick der Säugethiere nach ihrer Verteilung über die Welttheile". Abhandlungen der Königlichen Preußischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin. 1804−1811: 39–159. Archived from the original on 2019-06-08. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

- Driscoll, C. A.; Yamaguchi, N.; Bar-Gal, G. K.; Roca, A. L.; Luo, S.; Macdonald, D. W.; O'Brien, S. J. (2009). "Mitochondrial Phylogeography Illuminates the Origin of the Extinct Caspian Tiger and Its Relationship to the Amur Tiger". PLOS One. 4 (1): e4125. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.4125D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004125. PMC 2624500. PMID 19142238.

- Heptner, V. G.; Sludskij, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Tiger". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 95–202.

- Firouz, E. (2005). "Tiger". The complete fauna of Iran. London, New York: I. B. Tauris. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-1-85043-946-2.

- Humphreys, P.; Kahrom, E. (1999). "Caspian tiger". Lion and Gazelle: The Mammals and Birds of Iran. Avon: Images Publishing. pp. 75–77.

- Pocock, R. I. (1929). "Tigers". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 33 (3): 505–541.

- Kitchener, A. (1999). "Tiger distribution, phenotypic variation and conservation issues". In Seidensticker, J.; Christie, S.; Jackson, P. (eds.). Riding the Tiger: Tiger Conservation in Human-Dominated Landscapes. Cambridge University Press. pp. 19–39. ISBN 978-0-521-64835-6. Archived from the original on 2012-04-23.

- Wilting, A.; Courtiol, A.; Christiansen, P.; Niedballa, J.; Scharf, A. K.; Orlando, L.; Balkenhol, N.; Hofer, H.; Kramer-Schadt, S.; Fickel, J.; Kitchener, A., A. C. (2015). "Planning tiger recovery: Understanding intraspecific variation for effective conservation". Science Advances. 11 (5: e1400175): e1400175. Bibcode:2015SciA....1E0175W. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1400175. PMC 4640610. PMID 26601191.

- Li, Y.-C.; Sun, X.; Driscoll, C.; Miquelle, D. G.; Xu, X.; Martelli, P.; Uphyrkina, O.; Smith, J. L. D.; O’Brien, S. J.; Luo, S.-J. (2018). "Genome-wide evolutionary analysis of natural history and adaptation in the world's tigers". Current Biology. 28 (23): 3840–3849.e6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.09.019. PMID 30482605.

- Nowak, R. M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- Mazák, J. H. (2010). "Craniometric variation in the tiger (Panthera tigris): Implications for patterns of diversity, taxonomy and conservation". Mammalian Biology – Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 75 (1): 45–68. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2008.06.003.

- Kock, D. (1990). "Historical record of a tiger, Panthera tigris (Linnaeus, 1758), in Iraq". Zoology in the Middle East. 4: 11–15. doi:10.1080/09397140.1990.10637583.

- Can, Ö. E. (2004). Status, conservation and management of large carnivores in Turkey (PDF). Strasbourg: Convention on the conservation of European wildlife and natural habitats.

- Hatt, R. T. (1959). The mammals of Iraq. Ann Arbor: Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan.

- Masseti, M. (2009). "Carnivores of Syria". In E. Neubert; Z. Amr; S. Taiti; B. Gümüs (eds.). Animal Biodiversity in the Middle East. Proceedings of the First Middle Eastern Biodiversity Congress, Aqaba, Jordan, 20–23 October 2008. ZooKeys. ZooKeys 31: 229–252. pp. 229–252. doi:10.3897/zookeys.31.170.

- Faizolahi, K. (2016). Tiger in Iran – historical distribution, extinction causes and feasibility of reintroduction. Cat News Special issue 10: 5–13.

- Seidensticker, J.; Christie, S.; Jackson, P. (1999). "Preface". Riding the Tiger. Tiger conservation in human-dominated landscapes. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. pp. XV–XIX. ISBN 978-0-521-64835-6.

- Sunquist, M.; Karanth, K. U.; Sunquist, F. (1999). "Ecology, behaviour and resilience of the tiger and its conservation needs". In Seidensticker, J.; Christie, S.; Jackson, P. (eds.). Riding the Tiger. Tiger conservation in human-dominated landscapes. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press. pp. 5–18.

- Johnson, P. (1991). The birth of the Modern World Society, 1815–1830. New York: Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-016574-1.

- Jungius, H.; Chikin, Y.; Tsaruk, O.; Pereladova, O. (2009). Pre-Feasibility Study on the Possible Restoration of the Caspian Tiger in the Amu Darya Delta (PDF). WWF Russia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- Brower, D. R. (2003). Turkestan and the fate of the Russian Empire. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-29744-8.

- Ognev, S. I. (1935). "Carnivora (Fissipedia)". Mammals of the U.S.S.R. and adjacent countries. 2. Washington D. C.: National Science Foundation.

- Manuvera (2014-09-09). "The Last Iranian Tiger in Georgia". kavehfarrokh.com. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- Farrokh, K. (2015-03-21). "Turan Tiger Hunted in Central Asia in the 1930s". kavehfarrokh.com. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- Johnson, K. (2002). "The Status of mammalian carnivores in Turkey" (PDF). Endangered Species Update 19 (6): 232–237.

- Baytop, T. (1974). "La presence du vrai tigre, Panthera tigris (Linne 1758) en Turquie". Säugetierkundliche Mitteilungen. 22 (3): 254–256.

- Kumerloeve, H. (1974). "Zum Vorkommen des Tigers auf türkischem Boden". Säugetierkundliche Mitteilungen. 22 (4): 348–350.

- Ministry of Forest of Turkmenistan (1999). The Red Data Book of Turkmenistan. 1 (2nd ed.). Turkmenistan Publishing House.

- Sicker, M. (2001). Between Rome and Jerusalem: 300 years of Roman-Judaean relations. Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780275971403. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- Lukarevsky, V.; Akkiev, M.; Askerov, E.; Agili, A.; Can, E.; Gurielidze, Z.; Kudaktin, A.; Malkhasyan, A. & Yarovenko, Y. (2007). "Status of the Leopard in the Caucasus" (PDF). Cat News (Special Issue 2): 15–21.

- Stein, A.B.; Athreya, V.; Gerngross, P.; Balme, G.; Henschel, P.; Karanth, U.; Miquelle, D.; Rostro, S.; Kamler, J.F. & Laguardia, A. (2016). "Panthera pardus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Güldenstädt, J.A. (1787). Reisen durch Russland und im Caucasischen Gebürge (in Russian). St. Petersburg, Russia: Russian Imperial Academy of Sciences.

- Geptner, V. G.; Sludskij, A. A. (1992) [1972]. "Jungle Cat". Mlekopitajuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Moskva: Vysšaia Škola [Mammals of the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2. Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats)]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation. pp. 356–398.

- Gerngross, P. (2014). Recent records of jungle cat in Turkey. Cat News 61: 10–11.

- Ghoddousi, A., Hamidi, A. Kh., Ghadirian, T. and Bani’Assadi, S. (2016). The status of wildcat in Iran – a crossroad of subspecies? Cat News Special Issue 10: 60–63.

- Dybas, C. L. (2010). "The Once and Future Tiger". BioScience. 60 (11): 872–877. doi:10.1525/bio.2010.60.11.3.

- Luo, S.-J.; Johnson, W. E.; O'Brien, S. J. (2010). "Applying molecular genetic tools to tiger conservation". Integrative Zoology. 5 (4): 351–362. doi:10.1111/j.1749-4877.2010.00222.x. ISSN 1749-4877. PMC 6984346. PMID 21392353.

- Driscoll, C.A.; I. Chestin; H. Jungius; O. Pereladova; Y. Darman; E. Dinerstein; J. Seidensticker; J. Sanderson; S. Christie; S.J. Luo; M. Shrestha; Y. Zhuravlev; O. Uphyrkina; Y.V. Jhala; S.P. Yadav; D.G. Pikunov; N. Yamaguchi; D.E. Wildt; J.L.D. Smith; L. Marker; P.J. Nyhus; R. Tilson; D.W. Macdonald & S.J. O’Brien (2012). "A postulate for tiger recovery: the case of the Caspian Tiger". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 4 (6): 2637–2643. doi:10.11609/jott.o2993.2637-43. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17.

- "تاریخچه باغ وحش و نگهداری حیوانات وحشی در ایران/ مجمع الوحوش ناصری یا باغ وحش تهران". Animal Rights Watch (in Persian).

- Auguet, R. (1994). Cruelty and civilization: the Roman games. ISBN 978-0-415-10453-1.

- Andrade, N. J. (2013). Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World. p. 185. ISBN 9781107012059.

- Gawlikowski, M. (2006). "Palmyra". Current World Archaeology. 12: 32. ISSN 1745-5820.

- Kāshifī, H. V. (1854). The Anvari Suhaili; or the Lights of Canopus Being the Persian version of the Fables of Pilpay; or the Book Kalílah and Damnah rendered into Persian by Husain Vá'iz U'L-Káshifí. Translated by Eastwick, E. B. Hertford: Stephen Austin. Retrieved 2017-05-02.

- Şekercioğlu, Ç.H.; Anderson, S.; Akcay, E.; Bilgin, R.; Can, O.; Semiz, G. (2011). "Turkey's Globally Important Biodiversity In Crisis". Biological Conservation. 144 (12): 2752–2769. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2011.06.025.

Further reading

- Abbott, James (1856). A Narrative of a journey from Heraut to Khiva, Moscow and St. Petersburgh. 1. Khiva: James Madden. p. 26.

- Schnitzler, A.; Hermann, L. (2019-08-19). "Chronological distribution of the tiger Panthera tigris and the Asiatic lion Panthera leo persica in their common range in Asia". Mammal Review. Wiley Online Library. 49 (4): 340–353. doi:10.1111/mam.12166.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Panthera tigris virgata. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Panthera tigris virgata |

- "Caspian tiger (Panthera tigris virgata)". IUCN Cat Specialist Group.

- "The Great Cats of Asia: Caspian Tiger". wildtiger.org. Archived from the original on 2013-10-04.

- lairweb.org.nz: The Caspian Tiger

- Turanian tiger reintroduction (WWF)