Alemtuzumab

Alemtuzumab is a medication used to treat chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and multiple sclerosis.[1] In CLL has been used as both a first line and second line treatment.[1] In MS it is generally only recommended if other treatments have not worked.[1] It is given by injection into a vein.[1]

| |

| Monoclonal antibody | |

|---|---|

| Type | Whole antibody |

| Source | Humanized (from rat) |

| Target | CD52 |

| Clinical data | |

| Trade names | Campath, MabCampath, Lemtrada, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a608053 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous infusion |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Elimination half-life | ~288 hrs |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider |

|

| UNII | |

| ChEMBL | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C6468H10066N1732O2005S40 |

| Molar mass | 145454.20 g·mol−1 |

| | |

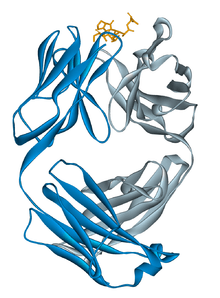

It is a monoclonal antibody that binds to CD52, a protein present on the surface of mature lymphocytes, but not on the stem cells from which these lymphocytes are derived. After treatment with alemtuzumab, these CD52-bearing lymphocytes are targeted for destruction.

Alemtuzumab was approved for medical use in the United States in 2001.[1] (Mab)Campath was withdrawn from the markets in the US and Europe in 2012 to prepare for a higher-priced relaunch of Lemtrada aimed at multiple sclerosis.[2]

Medical uses

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

Alemtuzumab is used for the treatment of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) in people who have been treated with alkylating agents and who have failed fludarabine therapy. It is an unconjugated antibody, thought to work via the activation of antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC).[3]

Multiple sclerosis

It is used for the relapsing remitting form of multiple sclerosis.[1] A 2017 Cochrane meta-analysis of studies comparing alemtuzumab to interferon beta 1a concluded that annual cycles of alemtuzumab probably reduces the proportion of people that experience relapse and may reduce the proportion of people who experience disability worsening and new T2 lesions on MRI, with adverse events found to be similarly high for both treatments.[4] However the low-to-moderate levels of evidence in the included, existing studies were noted and the need for larger high-quality randomised, double‐blind, controlled trials comparing mono or combination therapy with alemtuzumab was highlighted.[4] It is generally only recommended in people do not respond sufficiently to at least two other MS medications.[1]

Contraindications

Alemtuzumab is contraindicated in patients who have active systemic infections, underlying immunodeficiency (e.g., seropositive for HIV), or known Type I hypersensitivity or anaphylactic reactions to the substance.

Adverse effects

In November 2018, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a Safety Announcement[5] warning about rare but serious instances of stroke and blood vessel wall tears in multiple sclerosis patients who have received Lemtrada (alemtuzumab), mostly occurring within 1 day of initiating treatment and leading in some cases to permanent disability and even death.

In addition to the 13 cases to which the FDA Safety Announcement refers, a further 5 cases of spontaneous intracranial haemorrhage have been retrospectively identified from four US multiple sclerosis centres in correspondence published online in February 2019.[6]

On 12 April 2019, the Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) reported that it has started a review of the multiple sclerosis medicine Lemtrada (alemtuzumab) following new reports of immune-mediated conditions and of problems with the heart and blood vessels with this medicine, including fatal cases. PRAC advised that while the review is ongoing, Lemtrada should only be started in adults with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis that is highly active despite treatment with at least two disease-modifying therapies (a type of multiple sclerosis medicine) or where other disease-modifying therapies cannot be used. PRAC further advised that patients being treated with Lemtrada who are benefitting from it may continue treatment in consultation with their doctor.[7]

Very common adverse reactions associated with alemtuzumab infusion in MS patients include upper respiratory tract and urinary tract infections, herpes virus infections, lymphopenia, leucopenia, changes in thyroid function, tachycardia, skin rashes, pruritus, pyrexia, and fatigue.[8] The Summary of Product Characteristics provided in the electronic Medicines Compendium [eMC [9]] further lists common and uncommon adverse reactions that have been reported for Lemtrada, which include serious opportunistic nocardial infections and cytomegalovirus syndrome.[10][11][12]

Alemtuzumab can also precipitate autoimmune disease through the suppression of regulatory T cell populations and/or the emergence of autoreactive B-cells.[13][14]

Cases of multiple sclerosis reactivation/relapse have also been reported[15]

Biochemical properties

Alemtuzumab is a recombinant DNA-derived humanized IgG1 kappa monoclonal antibody that is directed against the 21–28 kDa cell surface glycoprotein CD52.[16]

History

The origins of alemtuzumab date back to Campath-1 which was derived from the rat antibodies raised against human lymphocyte proteins by Herman Waldmann and colleagues in 1983.[18] The name "Campath" derives from the pathology department of Cambridge University.

Initially, Campath-1 was not ideal for therapy because patients could, in theory, react against the foreign rat protein determinants of the antibody. To circumvent this problem, Greg Winter and his colleagues humanised Campath-1, by extracting the hypervariable loops that had specificity for CD52 and grafting them onto a human antibody framework. This became known as Campath-1H and serves as the basis for alemtuzumab.[19]

While alemtuzumab started life as a laboratory tool for understanding the immune system, within a short time it was clinically investigated for use to improve the success of bone marrow transplants and as a treatment for leukaemia, lymphoma, vasculitis, organ transplants, rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis.[20]

Campath as medication was first approved for B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia in 2001. It is marketed by Genzyme, which acquired the worldwide rights from Bayer AG in 2009. Genzyme was bought by Sanofi in 2011. In August/September 2012 Campath was withdrawn from the markets in the US and Europe. This was done to prevent off-label use of the drug to treat multiple sclerosis and to prepare for a relaunch under the trade name Lemtrada, with a different dosage aimed at multiple sclerosis treatment, this is expected to be much higher-priced.[2]

Bayer reserves the right to co-promote Lemtrada for 5 years, with the option to renew for an additional five years.

Sanofi acquisition and change of license controversy

In February 2011, Sanofi-Aventis, since renamed Sanofi, acquired Genzyme, the manufacturer of alemtuzumab.[21] The acquisition was delayed by a dispute between the two companies regarding the value of alemtuzumab. The dispute was settled by the issuance of Contingent Value Rights, a type of stock warrant which pays a dividend only if alemtuzumab reaches certain sales targets. The contingent value rights (CVR) trade on the NASDAQ-GM market with the ticker symbol GCVRZ.

In August 2012, Genzyme surrendered the licence for all presentations of alemtuzumab,[22] pending regulatory approval to re-introduce it as a treatment for multiple sclerosis. Concerns[23] that Genzyme would later bring to market the same product at a much higher price proved correct.

Research and off-label use

Graft-versus-host disease

A 2009 retrospective study of alemtuzumab (10 mg IV weekly) in 20 patients (no controls) with severe steroid-resistant acute intestinal graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) demonstrated improvement. Overall response rate was 70%, with complete response in 35%.[24] In this study, the median survival was 280 days. Important complications following this treatment included cytomegalovirus reactivation, bacterial infection, and invasive aspergillosis infection.[24]

References

- "Alemtuzumab Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- McKee, Selina (21 August 2012). "Sanofi withdraws Campath in US and EU". Pharma Times Online. Pharma Times.

- "About Campath". Genzyme. Archived from the original on 2011-07-14.

- Zhang, Jian; Shi, Shengliang; Zhang, Yueling; Luo, Jiefeng; Xiao, Yousheng; Meng, Lian; Yang, Xiaobo (27 November 2017). "Alemtuzumab versus interferon beta 1a for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: CD010968. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010968.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6486233. PMID 29178444.

- https://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/DrugSafety/UCM626584.pdf

- Azevedo CJ; Kutz C; Dix A; Boster A; Sanossian N; Kaplan J (2019). "Intracerebral haemorrhage during alemtuzumab administration". The Lancet. Neurology. 18 (4): 329–331. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30076-6. PMID 30777657.

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/meeting-highlights-pharmacovigilance-risk-assessment-committee-prac-8-11-april-2019

- https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5409#UNDESIRABLE_EFFECTS

- https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/

- Sheikh-Taha M; Corman LC (2017). "Pulmonary Nocardia beijingensis infection associated with the use of alemtuzumab in a patient with multiple sclerosis". Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 23 (6): 872–874. doi:10.1177/1352458517694431. PMID 28290754.

- Clerico M; De Mercanti S; Artusi CA; Durelli L; Naismith RT (2017). "Active CMV infection in two patients with multiple sclerosis treated with alemtuzumab". Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 23 (6): 874–876. doi:10.1177/1352458516688350. PMID 28290755.

- Brownlee WJ; Chataway J (2017). "Opportunistic infections after alemtuzumab: new cases of norcardial infection and cytomegalovirus syndrome" (PDF). Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 23 (6): 876–877. doi:10.1177/1352458517693440. PMID 28290753.

- Costelloe L; Jones J; Coles A (2012). "Secondary autoimmune diseases following alemtuzumab therapy for multiple sclerosis". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 12 (3): 335–341. doi:10.1586/ern.12.5. PMID 22364332.

- Aranha AA; Amer S; Reda ES; Broadley SA; Davoren PM (2013). "Autoimmune thyroid disease in the use of alemtuzumab for multiple sclerosis: a review". Endocrine Practice. 19 (5): 821–828. doi:10.4158/EP13020.RA. PMID 23757618.

- Wehrum T; Beume L-A; Stich O; Mader I; Mäurer M; Czaplinski A; Weiller C; Rauer S (2018). "Activation of disease during therapy with alemtuzumab in 3 patients with multiple sclerosis". Neurology. 90 (7): e601–e605. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000004950. PMID 29352101.

- A. Klement (7 January 2014). "Multiple-Sklerose-Behandlung". Österreichische Apothekerzeitung (in German) (1/2014): 24f.

- Ruxrungtham, K; Sirivichayakul, S; Buranapraditkun, S; Krause, W (2016). "Alemtuzumab-induced elimination of HIV-1-infected immune cells". Journal of Virus Eradication. 2 (1): 12–8. PMC 4946689. PMID 27482429.

- Hale G, Bright S, Chumbley G, et al. (October 1983). "Removal of T cells from bone marrow for transplantation: a monoclonal antilymphocyte antibody that fixes human complement". Blood. 62 (4): 873–82. doi:10.1182/blood.V62.4.873.873. PMID 6349718.

- Riechmann, Lutz; Clark, Michael; Waldmann, Herman; Winter, Greg (1988). "Reshaping human antibodies for therapy". Nature. 332 (6162): 323–7. Bibcode:1988Natur.332..323R. doi:10.1038/332323a0. PMID 3127726.

- "The life story of a biotechnology drug: Alemtuzumab". What is Biotechnology?.

- Whalen, Jeanne; Spencer, Mimosa (17 February 2011). "Sanofi Buys Genzyme for over $20 billion". The Wall Street Journal.(subscription required)

- Hussein, Jasmin (Genzyme) (9 August 2012). "Discontinuation of licensed supplies of alemtuzumab (Mabcampath)" (PDF). United Kingdom: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

- "Multiple sclerosis: New drug 'most effective'". BBC News. 1 November 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- Schnitzler, Marc; Hasskarl, Jens; Egger, Matthias; Bertz, Hartmut; Finke, Jürgen (2009). "Successful Treatment of Severe Acute Intestinal Graft-versus-Host Resistant to Systemic and Topical Steroids with Alemtuzumab". Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 15 (8): 910–8. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.04.002. PMID 19589480.