Graft-versus-host disease

Graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) is a syndrome, characterized by inflammation in different organs, with the specificity of epithelial cell apoptosis and crypt drop out.[1] GvHD is commonly associated with stem cell transplants such as those that occur with bone marrow transplants. GvHD also applies to other forms of transplanted tissues such as solid organ transplants.

| Graft-versus-host disease | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Emergency medicine |

White blood cells of the donor's immune system which remain within the donated tissue (the graft) recognize the recipient (the host) as foreign (non-self). The white blood cells present within the transplanted tissue then attack the recipient's body's cells, which leads to GvHD. This should not be confused with a transplant rejection, which occurs when the immune system of the transplant recipient rejects the transplanted tissue; GvHD occurs when the donor's immune system's white blood cells reject the recipient. The underlying principle (alloimmunity) is the same, but the details and course may differ. GvHD can also occur after a blood transfusion if the blood products used have not been irradiated or treated with an approved pathogen reduction system.

Signs and symptoms

In the classical sense, acute graft-versus-host-disease is characterized by selective damage to the liver, skin (rash), mucosa, and the gastrointestinal tract. Newer research indicates that other graft-versus-host-disease target organs include the immune system (the hematopoietic system, e.g., the bone marrow and the thymus) itself, and the lungs in the form of immune-mediated pneumonitis.[3] Biomarkers can be used to identify specific causes of GvHD, such as elafin in the skin.[4] Chronic graft-versus-host-disease also attacks the above organs, but over its long-term course can also cause damage to the connective tissue and exocrine glands[5] .

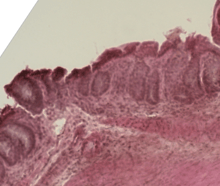

Acute GvHD of the GI tract can result in severe intestinal inflammation, sloughing of the mucosal membrane, severe diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting.[6] This is typically diagnosed via intestinal biopsy. Liver GvHD is measured by the bilirubin level in acute patients.[7] Skin GvHD results in a diffuse red maculopapular rash[8], sometimes in a lacy pattern.

Mucosal damage to the vagina can result in severe pain and scarring, and appears in both acute and chronic GvHD. This can result in an inability to have sexual intercourse.[9]

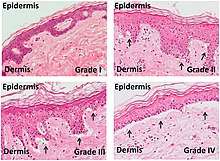

Acute GvHD is staged as follows: overall grade (skin-liver-gut) with each organ staged individually from a low of 1 to a high of 4. Patients with grade IV GvHD usually have a poor prognosis. If the GvHD is severe and requires intense immunosuppression involving steroids and additional agents to get under control, the patient may develop severe infections[10] as a result of the immunosuppression and may die of infection. However, a 2016 study found that the prognosis for patients with grade IV GvHD has improved in recent years.[11]

In the oral cavity, chronic graft-versus-host-disease manifests as lichen planus with a higher risk of malignant transformation to oral squamous cell carcinoma[12] in comparison to the classical oral lichen planus. Graft-versus-host-disease-associated oral cancer may have more aggressive behavior with poorer prognosis, when compared to oral cancer in non-hematopoietic stem cell transplantation patients.[13]

Types

In the clinical setting, graft-versus-host-disease is divided into acute and chronic forms, and scored or graded on the basis of the tissue affected and the severity of the reaction.[14][15]

- The acute or fulminant form of the disease (aGvHD) is normally observed within the first 100 days post-transplant,[16] and is a major challenge to transplants owing to associated morbidity and mortality.[17]

- The chronic form of graft-versus-host-disease (cGvHD) normally occurs after 100 days. The appearance of moderate to severe cases of cGVHD adversely influences long-term survival.[18]

Causes

Three criteria, known as the Billingham criteria, must be met in order for GvHD to occur.[19]

- An immuno-competent graft is administered, with viable and functional immune cells.

- The recipient is immunologically different from the donor – histo-incompatible.

- The recipient is immunocompromised and therefore cannot destroy or inactivate the transplanted cells.

After bone marrow transplantation, T cells present in the graft, either as contaminants or intentionally introduced into the host, attack the tissues of the transplant recipient after perceiving host tissues as antigenically foreign. The T cells produce an excess of cytokines, including TNF-α and interferon-gamma (IFNγ). A wide range of host antigens can initiate graft-versus-host-disease, among them the human leukocyte antigens (HLA).[20] However, graft-versus-host disease can occur even when HLA-identical siblings are the donors.[21] HLA-identical siblings or HLA-identical unrelated donors often have genetically different proteins (called minor histocompatibility antigens) that can be presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules to the donor's T-cells, which see these antigens as foreign and so mount an immune response.[22]

Antigens most responsible for graft loss are HLA-DR (first six months), HLA-B (first two years), and HLA-A (long-term survival).[23]

While donor T-cells are undesirable as effector cells of graft-versus-host-disease, they are valuable for engraftment by preventing the recipient's residual immune system from rejecting the bone marrow graft (host-versus-graft). In addition, as bone marrow transplantation is frequently used to treat cancer, mainly leukemias, donor T-cells have proven to have a valuable graft-versus-tumor effect.[24] A great deal of current research on allogeneic bone marrow transplantation involves attempts to separate the undesirable graft-vs-host-disease aspects of T-cell physiology from the desirable graft-versus-tumor effect.[25]

Transfusion-associated GvHD

This type of GvHD is associated with transfusion of un-irradiated blood to immunocompromised recipients. It can also occur in situations in which the blood donor is homozygous and the recipient is heterozygous for an HLA haplotype. It is associated with higher mortality (80–90%) due to involvement of bone marrow lymphoid tissue, however the clinical manifestations are similar to GVHD resulting from bone marrow transplantation. Transfusion-associated GvHD is rare in modern medicine. It is almost entirely preventable by controlled irradiation of blood products to inactivate the white blood cells (including lymphocytes) within.[26]

Thymus transplantation

Thymus transplantation may be said to be able to cause a special type of GvHD because the recipient's thymocytes would use the donor thymus cells as models when going through the negative selection to recognize self-antigens, and could therefore still mistake own structures in the rest of the body for being non-self. This is a rather indirect GvHD because it is not directly cells in the graft itself that causes it but cells in the graft that make the recipient's T cells act like donor T cells. It can be seen as a multiple-organ autoimmunity in xenotransplantation experiments of the thymus between different species.[27] Autoimmune disease is a frequent complication after human allogeneic thymus transplantation, found in 42% of subjects over 1 year post transplantation.[28] However, this is partially explained by the fact that the indication itself, that is, complete DiGeorge syndrome, increases the risk of autoimmune disease.[29]

Thymoma-associated multiorgan autoimmunity (TAMA)

A GvHD-like disease called thymoma-associated multiorgan autoimmunity (TAMA) can occur in patients with thymoma. In these patients rather than a donor being a source of pathogenic T cells, the patient's own malignant thymus produces self-directed T cells. This is because the malignant thymus is incapable of appropriately educating developing thymocytes to eliminate self-reactive T cells. The end result is a disease virtually indistinguishable from GvHD.[30]

Mechanism

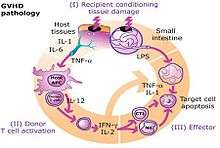

The pathophysiology of GvHD includes three phases:[31]

- The afferent phase: activation of APC (antigen presenting cells)

- The efferent phase: activation, proliferation, differentiation and migration of effector cells

- The effector phase: target tissue destruction

Activation of APC occurs in the first stage of GvHD. Prior to haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, radiation or chemotherapy results in damage and activation of host tissues, especially intestinal mucosa. This allows the microbial products to enter and stimulate pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and TNF-α. These proinflammatory cytokines increase the expression of MHC and adhesion molecules on APCs, thereby increasing the ability of APC to present antigen.[32] The second phase is characterized by the activation of effector cells. Activation of donor T-cells further enhances the expression of MHC and adhesion molecules, chemokines and the expansion of CD8 + and CD4 + T-cells and guest B-cells. In the final phase, these effector cells migrate to target organs and mediate tissue damage, resulting in multiorgan failure.[33]

Prevention

- DNA-based tissue typing allows for more precise HLA matching between donors and transplant patients, which has been proven to reduce the incidence and severity of GvHD and to increase long-term survival.[34]

- The T-cells of umbilical cord blood (UCB) have an inherent immunological immaturity,[35] and the use of UCB stem cells in unrelated donor transplants has a reduced incidence and severity of GvHD.[36]

- Methotrexate, cyclosporin and tacrolimus are common drugs used for GvHD prophylaxis.[37]

- Graft-versus-host-disease can largely be avoided by performing a T-cell-depleted bone marrow transplant. However, these types of transplants come at a cost of diminished graft-versus-tumor effect, greater risk of engraftment failure, or cancer relapse,[38] and general immunodeficiency, resulting in a patient more susceptible to viral, bacterial, and fungal infection. In a multi-center study, disease-free survival at 3 years was not different between T cell-depleted and T cell-replete transplants.[39]

Treatment

Intravenously administered glucocorticoids, such as prednisone, are the standard of care in acute GvHD[17] and chronic GVHD.[40] The use of these glucocorticoids is designed to suppress the T-cell-mediated immune onslaught on the host tissues; however, in high doses, this immune-suppression raises the risk of infections and cancer relapse. Therefore, it is desirable to taper off the post-transplant high-level steroid doses to lower levels, at which point the appearance of mild GVHD may be welcome, especially in HLA mis-matched patients, as it is typically associated with a graft-versus-tumor effect.. Cyclosporine and tacrolimus are calcineurin inhibitors. Both substances are structurally different but have the same mechanism of action. Cyclosporin binds to the cytosolic protein Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase A (known as cyclophilin), while tacrolimus binds to the cytosolic protein Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase FKBP12. These complexes inhibit calcineurin, block dephosphorylation of the transcription factor NFAT of activated T-cells and its translocation into the nucleus.[41] Standard prophylaxis involves the use of cyclosporine for six months with methotrexate. Cyclosporin levels should be maintained above 200 ng/ml.[42] Other substances that have been studied for GvHD treatment include, for example: sirolimus, pentostatin, etanercept, and alemtuzumab.[42]

In August 2017 the US FDA approved ibrutinib to treat chronic GvHD after failure of one or more other systemic treatments.[43]

Clinical research

There are a large number of clinical trials either ongoing or recently completed in the investigation of graft-versus-host disease treatment and prevention.[44]

On May 17, 2012, Osiris Therapeutics announced that Canadian health regulators approved Prochymal, its drug for acute graft-versus-host disease in children who have failed to respond to steroid treatment. Prochymal is the first stem cell drug to be approved for a systemic disease.[45]

In January 2016, Mesoblast released results of a Phase2 clinical trial on 241 children with acute Graft-versus-host disease, that was not responsive to steroids.[46] The trial was of a mesenchymal stem cell therapy known as remestemcel-L or MSC-100-IV. Survival rate was 82% (vs 39% of controls) for those who showed some improvement after 1 month, and in the long term 72% (vs 18% of controls) for those that showed little effect after 1 month.[46]

HIV elimination

Graft versus host disease has been implicated in eliminating several cases of HIV, including The Berlin Patient and 6 others in Spain. [47]

References

- Zhang, Lizhi; Chandan, Vishal S.; Wu, Tsung-Teh (2019). Surgical Pathology of Non-neoplastic Gastrointestinal Diseases. Springer. p. 144. ISBN 978-3-030-15573-5.

- Ghimire, Sakhila; Weber, Daniela; Mavin, Emily; Wang, Xiao nong; Dickinson, Anne Mary; Holler, Ernst (2017). "Pathophysiology of GvHD and Other HSCT-Related Major Complications". Frontiers in Immunology. 8: 79. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00079. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 5357769. PMID 28373870.

- Morisse-Pradier, H.; Nove-Josserand, R.; Philit, F.; Senechal, A.; Berger, F.; Callet-Bauchu, E.; Traverse-Glehen, A.; Maury, J.M.; et al. (2016). "Graft-versus-host disease, a rare complication of lung transplantation". Revue de Pneumologie Clinique. 72 (1): 101–107. doi:10.1016/j.pneumo.2015.05.004. PMID 26209034.

- Paczesny, S.; Levine, J.E.; Hogan, J.; Crawford, J.; Braun, T.M.; Wang, H.; Faca, V.; Zhang, Q.; et al. (2009). "Elafin is a Biomarker of Graft Versus Host Disease of the Skin". Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 15 (2): 13–4. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.12.039. PMC 2895410. PMID 20371463.

- Ogawa, Y.; Shimmura, S.; Dogru, M.; Tsubota, K. (2010). "Immune processes and pathogenic fibrosis in ocular chronic graft-versus-host disease and clinical manifestations after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation". Cornea. 29 (Nov Supplement 1): S68-77. doi:10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181ea9a6b. PMID 20935546.

- "Graft-versus-host disease". MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Krejci, M.; Kamelander, J.; Pospisil, Z.; Mayer, J. (2012). "Kinetics of bilirubin and liver enzymes is useful for predicting of liver graft-versus-host disease". Neoplasma. 59 (3): 264–268. doi:10.4149/neo_2012_034. PMID 22296496.

- Feito-Rodríguez, M.; de Lucas-Laguna, R.; Gómez-Fernández, C.; Sendagorta-Cudós, E.; Collantes, E.; Beato, M.J.; Boluda, E.R. (2013). "Cutaneous graft versus host disease in pediatric multivisceral transplantation". Pediatric Dermatology. 30 (3): 335–341. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2012.01839.x. PMID 22957989.

- Spiryda, L; Laufer, MR; Soiffer, RJ; Antin, JA (2003). "Graft-versus-host disease of the vulva and/or vagina: Diagnosis and treatment". Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 9 (12): 760–5. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2003.08.001. PMID 14677115.

- "Graft-versus-host disease". MedlinePlus. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- El-Jawahri, A.; Li, S.; Antin, J.H.; Spitzer, T.R.; Armand, P.A.; Koreth, J.; Nikiforow, S.; Ballen, K.K.; Ho, V.T.; Alyea, E.P.; Dey, B.R.; McAfee, S.L.; Glotzbecker, B.E.; Soiffer, R.J.; Cutler, C.S.; Chen, Y.B. (2016). "Improved Treatment-Related Mortality and Overall Survival of Patients with Grade IV Acute GVHD in the Modern Years". Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation: Journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 22 (5): 910–918. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.12.024. PMID 26748160.

- Tsukada, S.; Itonaga, H.; Taguchi, J.; Miyoshi, T.; Hayashida, S.; Sato, S.; Ando, K.; Sawayama, Y.; Imaizumi, Y.; Hata, T.; Umeda, M.; Niino, D.; Miyazaki, Y. (2019). "Gingival squamous cell carcinoma diagnosed on the occasion of osteonecrosis of the jaw in a patient with chronic GVHD". Rinsho Ketsueki. 60 (1): 22–27. doi:10.11406/rinketsu.60.22. PMID 30726819.

- Elad, Sharon; Zadik, Yehuda; Zeevi, Itai; Miyazaki, Akihiro; De Figueiredo, Maria A. Z.; Or, Reuven (2010). "Oral Cancer in Patients After Hematopoietic Stem-Cell Transplantation: Long-Term Follow-Up Suggests an Increased Risk for Recurrence". Transplantation. 90 (11): 1243–4. doi:10.1097/TP.0b013e3181f9caaa. PMID 21119507.

- Martino R, Romero P, Subirá M, Bellido M, Altés A, Sureda A, Brunet S, Badell I, Cubells J, Sierra J (1999). "Comparison of the classic Glucksberg criteria and the IBMTR Severity Index for grading acute graft-versus-host disease following HLA-identical sibling stem cell transplantation. International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry". Bone Marrow Transplantation. 24 (3): 283–287. doi:10.1038/sj.bmt.1701899. PMID 10455367.

- Filipovich AH, Weisdorf D, Pavletic S, Socie G, Wingard JR, Lee SJ, Martin P, Chien J, Przepiorka D, Couriel D, Cowen EW, Dinndorf P, Farrell A, Hartzman R, Henslee-Downey J, Jacobsohn D, McDonald G, Mittleman B, Rizzo JD, Robinson M, Schubert M, Schultz K, Shulman H, Turner M, Vogelsang G, Flowers ME (2005). "National Institutes of Health consensus development project on criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease: I. Diagnosis and staging working group report". Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 11 (12): 945–956. doi:10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.09.004. PMC 4329079. PMID 16338616.

- Funke, V.A.; Moreira, M.C.; Vigorito, A.C. (2016). "Acute and chronic Graft-versus-host disease after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation". Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira. 62 (supl 1): 44–50. doi:10.1590/1806-9282.62.suppl1.44. PMID 27982319.

- Goker, H; Haznedaroglu, IC; Chao, NJ (2001). "Acute graft-vs-host disease Pathobiology and management". Experimental Hematology. 29 (3): 259–77. doi:10.1016/S0301-472X(00)00677-9. PMID 11274753.

- Lee, Stephanie J.; Vogelsang, Georgia; Flowers, Mary E.D. (2003). "Chronic graft-versus-host disease". Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 9 (4): 215–33. doi:10.1053/bbmt.2003.50026. PMID 12720215.

- Billingham, R.E. (1966). "The biology of graft-versus-host-reactions". Harvey Lectures. 1966–1967 (62): 21–78. PMID 4875305.

- Kanda, J. (2013). "Effect of HLA mismatch on acute graft-versus-host disease". International Journal of Hematology. 98 (3): 300–308. doi:10.1007/s12185-013-1405-x. PMID 23893313.

- Bonifazi, F.; Solano, C.; Wolschke, C.; Sessa, M.; et al. (2019). "Acute GVHD prophylaxis plus ATLG after myeloablative allogeneic haemopoietic peripheral blood stem-cell transplantation from HLA-identical siblings in patients with acute myeloid leukaemia in remission: final results of quality of life and long-term outcome analysis of a phase 3 randomised study". Lancet Haematology. 6 (2): e89–e99. doi:10.1016/S2352-3026(18)30214-X. hdl:10138/311714. PMID 30709437.

- Taylor CJ, Bolton EM, Bradley JA (2011). "Immunological considerations for embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cell banking". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 366 (1575): 2312–2322. doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0030. PMC 3130422. PMID 21727137.

- Solomon S, Pitossi F, Rao MS (2015). "Banking on iPSC – is it doable and is it worthwhile". Stem Cell Reviews. 11 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1007/s12015-014-9574-4. PMC 4333229. PMID 25516409.

- Falkenburg, J.H.F.; Jedema, I. (2017). "Graft versus tumor effects and why people relapse". Hematology. December (1): 693–698. doi:10.1182/asheducation-2017.1.693. PMC 6142614. PMID 29222323.

- Sun, K.; Li, M.; Sayers, T.J.; Welniak, L.A.; Murphy, W.J. (2008). "Differential effects of donor T-cell cytokines on outcome with continuous bortezomib administration after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation". Blood. 112 (4): 1522–1529. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-03-143461. PMC 2515132. PMID 18539902.

- Moroff, G; Leitman, SF; Luban, NL (1997). "Principles of blood irradiation, dose validation, and quality control". Transfusion. 37 (10): 1084–1092. doi:10.1046/j.1537-2995.1997.371098016450.x. PMID 9354830.

- Xia, G.; Goebels, J.; Rutgeerts, O.; Vandeputte, M.; Waer, M. (2001). "Transplantation tolerance and autoimmunity after xenogeneic thymus transplantation". Journal of Immunology. 166 (3): 1843–1854. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.166.3.1843. PMID 11160231.

- Markert, M. Louise; Devlin, Blythe H.; McCarthy, Elizabeth A.; Chinn, Ivan K.; Hale, Laura P. (2008). "Thymus Transplantation". In Lavini, Corrado; Moran, Cesar A.; Morandi, Uliano; et al. (eds.). Thymus Gland Pathology: Clinical, Diagnostic, and Therapeutic Features. pp. 255–267. doi:10.1007/978-88-470-0828-1_30. ISBN 978-88-470-0827-4.

- Markert, M. L.; Devlin, B. H.; Alexieff, M. J.; Li, J.; McCarthy, E. A.; Gupton, S. E.; Chinn, I. K.; Hale, L. P.; et al. (2007). "Review of 54 patients with complete DiGeorge anomaly enrolled in protocols for thymus transplantation: Outcome of 44 consecutive transplants". Blood. 109 (10): 4539–47. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-10-048652. PMC 1885498. PMID 17284531.

- Wadhera A, Maverakis E, Mitsiades N, Lara PN, Fung MA, Lynch PJ (October 2007). "Thymoma-associated multiorgan autoimmunity: a graft-versus-host-like disease". J Am Acad Dermatol. 57 (4): 683–689. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.02.027. PMID 17433850.

- Tabbara, Imad; Elbahesh, Ehab; Rafei, Hind; Nassereddine, Samah (2017-04-01). "Acute Graft Versus Host Disease: A Comprehensive Review". Anticancer Research. 37 (4): 1547–1555. doi:10.21873/anticanres.11483. ISSN 0250-7005. PMID 28373413.

- Roncarolo, Maria-Grazia; Battaglia, Manuela (August 2007). "Regulatory T-cell immunotherapy for tolerance to self antigens and alloantigens in humans". Nature Reviews Immunology. 7 (8): 585–598. doi:10.1038/nri2138. PMID 17653126.

- Zhang, L.; Chu, J.; Yu, J.; Wei, W. (7 December 2015). "Cellular and molecular mechanisms in graft-versus-host disease". Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 99 (2): 279–287. doi:10.1189/jlb.4ru0615-254rr. PMID 26643713.

- Morishima, Y.; Sasazuki, T; Inoko, H; Juji, T; Akaza, T; Yamamoto, K; Ishikawa, Y; Kato, S; et al. (2002). "The clinical significance of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) allele compatibility in patients receiving a marrow transplant from serologically HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DR matched unrelated donors". Blood. 99 (11): 4200–6. doi:10.1182/blood.V99.11.4200. PMID 12010826.

- Grewal, S. S.; Barker, JN; Davies, SM; Wagner, JE (2003). "Unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation: Marrow or umbilical cord blood?". Blood. 101 (11): 4233–44. doi:10.1182/blood-2002-08-2510. PMID 12522002. S2CID 6486524.

- Laughlin, Mary J.; Barker, Juliet; Bambach, Barbara; Koc, Omer N.; Rizzieri, David A.; Wagner, John E.; Gerson, Stanton L.; Lazarus, Hillard M.; et al. (2001). "Hematopoietic Engraftment and Survival in Adult Recipients of Umbilical-Cord Blood from Unrelated Donors". New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (24): 1815–22. doi:10.1056/NEJM200106143442402. PMID 11407342.

- Törlén, J.; Ringdén, O.; Garming-Legert, K.; Ljungman, P.; Winiarski, J.; Remes, K.; Itälä-Remes, M.; Remberger, M.; Mattsson, J. (2016). "A prospective randomized trial comparing cyclosporine/methotrexate and tacrolimus/sirolimus as graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation". Haematologica. 101 (11): 1417–1425. doi:10.3324/haematol.2016.149294. PMC 5394879. PMID 27662016.

- Hale, G; Waldmann, H (1994). "Control of graft-versus-host disease and graft rejection by T cell depletion of donor and recipient with Campath-1 antibodies. Results of matched sibling transplants for malignant diseases". Bone Marrow Transplantation. 13 (5): 597–611. PMID 8054913.

- Wagner, John E; Thompson, John S; Carter, Shelly L; Kernan, Nancy A; Unrelated Donor Marrow Transplantation Trial (2005). "Effect of graft-versus-host disease prophylaxis on 3-year disease-free survival in recipients of unrelated donor bone marrow (T-cell Depletion Trial): A multi-centre, randomised phase II–III trial". The Lancet. 366 (9487): 733–41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66996-6. PMID 16125590.

- Menillo, S A; Goldberg, S L; McKiernan, P; Pecora, A L (2001). "Intraoral psoralen ultraviolet a irradiation (PUVA) treatment of refractory oral chronic graft-versus-host disease following allogeneic stem cell transplantation". Bone Marrow Transplantation. 28 (8): 807–8. doi:10.1038/sj.bmt.1703231. PMID 11781637.

- Liu, J; Farmer JD, Jr; Lane, WS; Friedman, J; Weissman, I; Schreiber, SL (23 August 1991). "Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes". Cell. 66 (4): 807–15. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(91)90124-h. PMID 1715244.

- Mandanas, Romeo A. "Graft Versus Host Disease Treatment & Management: Medical Care". Medscape. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- FDA expands ibrutinib indications to chronic GVHD. Aug 2017

- search of clinicaltrials.gov for Graft-versus-host disease

- "World's First Stem-Cell Drug Approval Achieved in Canada". The National Law Review. Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP. 2012-06-12. Retrieved 2012-07-01.

- "Increased Survival Using MSB Cells In Children With aGVHD". Retrieved 22 Feb 2016.

- "Immune war with donor cells after transplant may wipe out HIV". ?. NewScientist. 2017-05-03. Retrieved 2018-11-23.

Further reading

- Ferrara JLM, Deeg HJ, Burakoff SJ. Graft-Vs.-Host Disease: Immunology, Pathophysiology, and Treatment. Marcel Dekker, 1990 ISBN 0-8247-9728-0

- Polsdorfer, JR Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine: Graft-vs.-host disease

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |