Yaoi

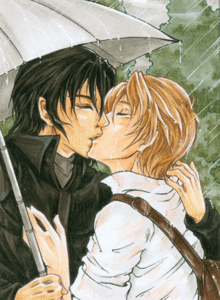

Yaoi (/ˈjaʊi/; Japanese: やおい [ja.o.i]), also known as boys' love (ボーイズ ラブ, bōizu rabu) or BL (ビーエル, bīeru), is a genre of fictional media originating in Japan that features homoerotic relationships between male characters.[1] It is typically created by women for women and is distinct from homoerotic media marketed to gay and bisexual male audiences, such as bara, but it can also attract male readers and male creators can also produce it. It spans a wide range of media, including manga, anime, drama CDs, novels, games, films, and fan production. Boys' love and its abbreviation, BL, are the generic terms for this kind of media in Japan and have, in recent years, become more commonly used in English as well. However, yaoi remains more generally prevalent in English.

A defining characteristic of yaoi is the practice of pairing characters in relationships according to the roles of seme, the sexual top or active pursuer, and uke, the sexual bottom or passive pursued. Common themes in yaoi include forbidden relationships, depictions of rape, tragedy, and humor. Yaoi and BL stories cover a diverse range of genres such as high school love comedy, period drama, science fiction and fantasy, and detective fiction, and include sub-genres such as omegaverse and shotacon.

Yaoi finds its origins in both fan culture and commercial publishing. As James Welker has summarized, the term yaoi dates back to dōjinshi culture of the late 1970s to early 1980s where, as a portmanteau of yamanashi ochinashi iminashi ("no climax, no point, no meaning"), it was a self-deprecating way to refer to amateur fan works that parodied mainstream manga and anime by depicting the male characters from popular series in vaguely or explicitly sexual situations and in the manga they are often explicitly shown.[2] The use of yaoi to refer to parody dōjinshi is still predominant in Japan. In commercial publishing, the genre can be traced back to shōnen-ai, a genre of beautiful boy manga that began to appear in shōjo manga magazines in the early 1970s. From the 1970s to 1980s, other terms such as tanbi and juné emerged to refer to specific developments in the genre. In the early 1990s, however, these terms were largely eclipsed with the commercialization of male-male homoerotic media under the label of boys' love.

Yaoi has a robust global presence. Yaoi works are available across the continents in various languages both through international licensing and distribution and through circulation by fans. Yaoi works, culture, and fandom have also been studied and discussed by scholars and journalists worldwide.

History and general terminology

The genre currently known as boys' love, BL, or yaoi derives from two sources. Female authors writing for shōjo (girl's) manga magazines in the early 1970s published stories featuring platonic relationships between young boys, which were known as tanbi (耽美, "aesthetic") or shōnen-ai (少年愛, "boy love"). In the late 1970s going into the 1980s, women and girls in the dōjinshi (fan fiction) markets of Japan started to produce sexualized parodies of popular shōnen (boy's) manga and anime stories in which the male characters were recast as gay lovers.[nb 1] By the end of the 1970s, magazines devoted to the nascent genre started to appear, and in the 1990s the term "boys' love" or "BL" would be invented and would become the dominant term used for the genre in Japan. Although yaoi derives from girl's and women's manga and still targets the shōjo and josei demographics, it is currently considered a separate category.[4][5]

Keiko Takemiya's manga serial Kaze to Ki no Uta,[nb 2] first published in 1976, was groundbreaking in its depictions of "openly sexual relationships" between men, spurring the development of the boys' love genre in shōjo manga,[6] as well as the development of sexually explicit amateur comics.[9] Another noted female manga author, Kaoru Kurimoto, wrote shōnen-ai mono stories in the late 1970s that have been described as "the precursors of yaoi".[10]

The term yaoi is an acronym created in the late 1970s[3] by Yasuko Sakata and Akiko Hatsu[10] from the words yama nashi, ochi nashi, imi nashi (山[場]なし、落ちなし、意味なし, "no peak (climax), no fall (punch line/denouement), no meaning"). This phrase was first used as a "euphemism for the content"[11] and refers to how yaoi, as opposed to the "difficult to understand" shōnen-ai being produced by the Year 24 Group female manga authors,[12] focused on "the yummy parts".[8] The phrase also parodies a classical style of plot structure.[13] Kubota Mitsuyoshi says that Osamu Tezuka used yama nashi, ochi nashi, imi nashi to dismiss poor quality manga, and this was appropriated by the early yaoi authors.[11] As of 1998, the term yaoi was considered "common knowledge to manga fans".[14] A joking alternative yaoi acronym among fujoshi (female yaoi fans) is yamete, oshiri ga itai (やめて お尻が 痛い, "stop, my ass hurts!").[15][16] In the 1980s, the genre was presented in an anime format for the first time, including the works Patalliro! (1982) which showed a romance between two supporting characters, an adaptation of Kaze to Ki no Uta (1987) and Earthian (1989), released in the original video animation (home video) format.[17]

Prior to the popularization of the term yaoi, material in the nascent genre was called juné (ジュネ),[4] a name derived from June, a magazine that published male-male tanbi romances which took its name from the homoerotic stories of the French writer Jean Genet.[4][18] In China, the term danmei is used, which is derived from tanbi.[19] The term "bishōnen manga" was used in the 1970s, but fell from favor in the 1990s when manga in this genre began to feature a broader range of protagonists beyond the traditional adolescent boys.[20] In Japan, the term juné would die out in favor of "boys' love", which remains the most common name in Japan.[4] Mizoguchi suggests that publishers wishing to get a foothold in the juné market coined "boys' love" to disassociate the genre from the publisher of June.[20]

While yaoi has become an umbrella term in the West for women's manga or Japanese-influenced comics with male-male relationships,[4] and it is the term preferentially used by American manga publishers for works of this kind,[21] Japan uses the term yaoi to denote dōjinshi and works that focus on sex scenes.[4] In both usages, yaoi / boys' love excludes gei comi (bara), a genre which also depicts gay male sexual relationships, but is written for and mostly by gay men.[4][13] In the West, the term hentai yaoi is sometimes used to denote the most explicit titles.[22] The use of yaoi to denote those works with explicit scenes sometimes clashes with use of the word to describe the genre as a whole, creating confusion between Japanese and Western writers or between Western fans who insist on proper usage of the Japanese terms and those who use the Westernized versions. Yaoi can also be used by Western fans as a label for anime or manga-based slash fiction.[23] In Japan, the term yaoi is occasionally written as "801",[24] which can be read as yaoi through Japanese wordplay:[11] the short reading of the number eight is "ya", zero can be read as "o" (a Western influence), while the short reading for one is "i".[25]

Concepts

Shōnen-ai

The term shōnen-ai ("boy love") originally connoted ephebophilia or pederasty in Japan, but from the early 1970s to the late 1980s, was used to describe a new genre of shōjo manga, primarily produced by the Year 24 Group of women authors, about beautiful boys in love. Characteristics of shōnen-ai include exoticism, often taking place in Europe,[26] and idealism.[27] Jeffrey Angles particularly notes Moto Hagio's The Heart of Thomas (1974) and Keiko Takemiya's Kaze to Ki no Uta (1976–1984) as being groundbreaking, noting their portrayal of intense friendship between males, including jealousy and desire.[28]

The origin of shōnen-ai is thought to come through two pathways. Mizoguchi traces the tales back to the tanbi romances of Mori Mari.[29] The term tanbi was used for stories written for and about the worship of beauty,[4] and romance between older men and beautiful youths[30] using particularly flowery language and unusual kanji (Chinese characters appropriated into Japanese script).[4] Mori Mari in Koibito-tachi no Mori (恋人たちの森, "A Lovers' Forest"), considered "the first work of [yaoi]",[31] used such unusual kanji for her characters' names that she converted to spelling their names in katakana, a script used to transcribe foreign words.[30] The word was originally used to describe an author's distinctive style, for example, the styles of Yukio Mishima and Jun'ichirō Tanizaki. Akiko Mizoguchi describes its application to male-male stories as "misleading", but notes "it was the most commonly used term in the early 1990s."[20] According to James Welker, Minori Ishida shows that "early boys' love narratives" were inspired by European fiction about "beautiful boys", and the writing of the male author Taruho Inagaki.[29] Carola Bauer cites the bildungsroman genre as having influenced shōnen-ai.[32]

Kazuko Suzuki describes shōnen-ai as being "pedantic" and "difficult to understand",[12] saying that they required "knowledge of classic literature, history and science"[27] and were replete with "philosophical and abstract musings". Shōnen-ai challenged young readers, who were often only able to understand the references and deeper themes as they grew older and instead were initially drawn to the figure of the male protagonist.[33] Galbraith defines shōnen-ai as "original content that can approach serious literature in tone and theme", as opposed to a more light-hearted yaoi.[3] By the late 1980s, the popularity of professionally published shōnen-ai was declining, and dōjinshi (self-published) yaoi was becoming more popular.[8]

The terms yaoi and shōnen-ai are sometimes used by Western fans to differentiate between two variants of the genre. In this case, yaoi is used to describe titles that primarily feature sexually explicit themes and sex scenes, while shōnen-ai is used to describe titles that focus primarily on romance and omit explicit sexual content, although sexual acts may be implied.[34][35][36] According to this use of the terms, Gravitation would be considered shōnen-ai due to its focus on the characters' careers rather than their love life.[22]

Seme and uke

The two participants in a yaoi relationship (and to a lesser extent in yuri)[37] are often referred to as seme (攻め, "top") and uke (受け, "bottom").[38] These terms originated in martial arts:[39] seme derives from the ichidan verb "to attack", while uke is taken from the verb "to receive"[14] and is used in Japanese gay slang to mean the receptive partner ("bottom") in anal sex. Aleardo Zanghellini suggests that the martial arts terms have special significance to a Japanese audience, as an archetype of the gay male relationship in Japan includes same-sex love between samurai and their companions.[39] The seme and uke are often drawn in the bishōnen style and are "highly idealised", blending both masculine and feminine qualities.[14]

Zanghellini suggests that the samurai archetype is responsible for "the 'hierarchical' structure and age difference" of some relationships portrayed in yaoi and boys' love.[39] The seme is often depicted as the stereotypical male of anime and manga culture: restrained, physically powerful, and protective. The seme is generally older and taller,[40] with a stronger chin, shorter hair, smaller eyes, and a more stereotypically masculine, and "macho"[41] demeanour than the uke. The seme usually pursues the uke, who often has softer, androgynous, feminine features with bigger eyes and a smaller build, and is often physically weaker than the seme.[21] Another way the seme and uke characters are shown is through who is dominant in the relationship; a character can take the uke role even if he is not presented as feminine, simply by being juxtaposed against and pursued by a more dominant, more masculine, character.[42]

Although not the same, a yaoi construct similar to "seme and uke" is the concept of "tachi and neko". This archetypal pairing is referenced more often in older yaoi volumes; in modern yaoi, this pairing is often seen as already encompassed by seme and uke or simply unnecessary to address. The tachi (タチ) partner is conceptualized as the member of the relationship who pursues the more passive partner, the latter of whom is referred to as the neko (ネコ). Seme and uke is similar but not identical to tachi and neko because the former refers primarily to sexual roles, whereas the latter describes personality. Although seme and uke roles are already used in some manga to describe which member of the relationship is more dominant and which member is more passive, there are just as many manga novels which subtly or overtly differentiate between the two.

Anal sex is a prevalent theme in yaoi, as nearly all stories feature it in some way. The storyline where an uke is reluctant to have anal sex with a seme is considered to be similar to the reader's reluctance to have sexual contact with someone for the first time.[43] Zanghellini notes that illustrations of anal sex almost always position the characters to face each other, rather than "doggy style". Zanghellini also notes that the uke rarely fellates the seme, but instead receives the sexual and romantic attentions of the seme.[39]

Though these tropes are common in yaoi, not all works adhere to them.[44][45] Carola Bauer states that the "butch-femme" couple dynamic discussed above became essential in the commercially published fiction of the 1990s.[46] McLelland says that authors are "interested in exploring, not repudiating" the dynamics between the seme and uke.[47] The possibility of switching roles is often a source of playful teasing and sexual excitement for the characters, indicating an interest among many genre authors in exploring the "performative nature" of the roles.[36] Sometimes the bottom character will be the aggressor in the relationship,[nb 3] or the pair will switch their sexual roles.[49] Riba (リバ), a contraction of the English word "reversible", is used to describe a couple that yaoi fans think is still plausible when the partners switch their seme and uke roles.[48] In another common mode of characters, the author will forgo the stylisations of the seme and uke, and will portray both lovers as "equally attractive handsome men". In this case, whichever of the two who is ordinarily in charge will take the passive role during sex.[41]

Bara

Although sometimes conflated with yaoi by Western commentators, gay men's manga or gei comi, also called "men's love" ("ML") in English and bara in Japan, caters to a gay male audience rather than a female one and tends to be produced primarily by gay and bisexual male artists (such as Gengoroh Tagame) and serialized in gay men's magazines.[50] Bara is a smaller niche genre in Japan than yaoi manga.[51] Considered a subgenre of seijin (men's erotica) for gay males, bara more closely resembles comics for men (seinen) rather than comics written for female readers (shōjo/josei). Few titles have been licensed or scanlated for English-language markets.[51]

Bara does not aim to recreate the heteronormative gender roles between the masculine seme and feminine uke types prominent in yaoi that is generally for a female audience. Gay men's manga is unlikely to contain scenes of "uncontrollable weeping or long introspective pauses",[52] and is less likely than yaoi to "build up a strong sense of character" before sex scenes occur.[53] The men in bara comics are more likely to be stereotypically masculine in behaviour and are illustrated as "hairy, very muscular, or [having] a few excess pounds"[52] akin to beefcakes or bears in gay culture. While bara usually features gay romanticism and adult content, sometimes of a violent or exploitative nature, it often explores real-world or autobiographical themes and acknowledges the taboo nature of homosexuality in Japan.

The gachi muchi ("muscley-chubby") subgenre of boys' love, also termed bara among English-speaking fans,[54] represents a crossover between bara and yaoi, with considerable overlap of writers, artists and art styles. This emergent boys' love subgenre, while still marketed primarily to women, depicts more masculine body types and is more likely to be written by gay male authors and artists; it is also thought to attract a large crossover gay male audience.[55] Prior to the development of gachi muchi, the greatest overlap between yaoi and bara authors was in BDSM-themed publications[54] such as Zettai Reido, a yaoi anthology magazine which had a number of openly male contributors.[15] Several female yaoi authors who have done BDSM-themed yaoi have been recruited to contribute stories to BDSM-themed bara anthologies or special issues.[54]

Thematic elements

Diminished female characters

Female characters often have very minor roles in yaoi, or are absent altogether.[56][57] Suzuki notes that mothers in particular are portrayed in a negative light, for instance in Zetsuai 1989 in which the main character as a child witnesses his mother murdering his father. Suzuki suggests this is because the character and reader alike are seeking to substitute the absence of unconditional maternal love with the "forbidden" all-consuming love presented in yaoi.[58] Nariko Enomoto, a yaoi author, states that when women are depicted in yaoi, "it can't help but become weirdly real".[59] When fans produce yaoi from series that contain female characters, such as Gundam Wing,[60] the female's role is typically either minimized or the character is killed off.[57] Yukari Fujimoto states of shōnen manga series used as inspiration for yaoi that "it seems that yaoi readings and likeable female characters are mutually exclusive."[61]

Early shōnen-ai and yaoi have been regarded as misogynistic, but Lunsing notes a decrease in misogynistic comments from characters and regards the development of the yuri genre as reflecting a reduction of internal misogyny.[15] Alternatively, yaoi fandom is also viewed as a "refuge" from mainstream culture, which in this paradigm is viewed as inherently misogynistic.[62] In recent years, it has become more popular to have a female character supporting the couple.[63] Yaoi author Fumi Yoshinaga usually includes at least one sympathetic female character in her works.[64] There are many female characters in yaoi who are fujoshi themselves.

Gay equality

Yaoi stories are often strongly homosocial, which gives the men freedom to bond with each other and to pursue shared goals together, as in dojinshi representations of Captain Tsubasa, or to rival each other, as in Haru wo Daiteita. This spiritual bond and equal partnership overcomes the male-female power hierarchy.[65] To be together, many couples depicted in conventional yaoi stories must overcome obstacles that are often emotional or psychological rather than physical. The theme of the protagonists' victory in yaoi has been compared favourably to Western fairy tales, as the latter intends to enforce the status quo, but yaoi is "about desire" and seeks "to explore, not circumscribe, possibilities".[66] Akiko Mizoguchi noted that while homosexuality is sometimes still depicted as "shameful" to heighten dramatic tension, yaoi has increasingly featured stories of coming out and the characters' gradual acceptance within the wider community, such as Brilliant Blue. Mizoguchi remarked that yaoi presents a far more gay-friendly depiction of Japanese society, which she contends is a form of activism among yaoi authors.[67] Some longer-form stories, such as FAKE and Kizuna, depict the couple moving in together and adopting.[68]

Although gay male characters are empowered in yaoi manga, the manga rarely explicitly addresses the reality of homophobia in Japanese society. According to Hisako Miyoshi, vice editor-in-chief for Libre Publishing, while earlier yaoi focused "more on the homosexual way of life from a realistic perspective", over time the genre has become less realistic and more comedic, and the stories are "simply for entertainment".[69] Yaoi manga often have fantastical, historical or futuristic settings, and many fans consider the genre to be an "escapist fantasy".[70] Homophobia, when it is presented as an issue at all,[44] is used as a plot device to "heighten the drama",[71] or to show the purity of the leads' love. Rachel Thorn has suggested that readers of the yaoi genre, which primarily features romantic narratives, may be turned off by strong political themes such as homophobia.[8] Makoto Tateno stated her scepticism that a focus on real gay issues will "[become] a trend, because girls like fiction more than realism".[72] Alan Williams argues that the lack of a gay identity in yaoi is due to yaoi being postmodernist.[73]

Rape

Rape fantasy is a theme commonly found in yaoi manga.[65] Anal intercourse is understood as a means of expressing commitment to a partner, and in yaoi, the "apparent violence" of rape is transformed into a "measure of passion". While Japanese society often shuns or looks down upon women who are raped in reality, the yaoi genre depicts men who are raped as still "imbued with innocence" and are typically still loved by their rapists after the act, a trope that may have originated with Kaze to Ki no Uta.[74] Rape scenes in yaoi are rarely presented as crimes with an assaulter and a victim: scenes where a seme rapes an uke are not depicted as symptomatic of the "disruptive sexual/violent desires" of the seme, but instead are a signifier of the "uncontrollable love" felt by a seme for an uke. Such scenes are often a plot device used to make the uke see the seme as more than just a good friend and typically result in the uke falling in love with the seme.[65] Rape fantasy themes explore the protagonist's lack of responsibility in sex, leading to the narrative climax of the story, where "the protagonist takes responsibility for his own sexuality".[75]

The 2003–2005 manga series Under Grand Hotel, set in a men's prison, has been praised for showing a more realistic depiction of rape.[76] Authors such as Fusanosuke Inariya (of Maiden Rose fame) utilize rape not as the traditional romantic catalyst, but as a tragic dramatic plot element, rendering her stories a subversion of contemporary tropes that reinforce and reflect older tropes such as the prevalence of romantic tragedy themes. Other yaoi tend to depict a relationship that begins as non-consensual and evolves into a consensual relationship. However, Fusanosuke's stories are ones where the characters' relationship begins as consensual and devolves into non-consensual, often due to external societal pressures that label the character's gay relationship as deviant. Her stories are still characterized by fantasy, yet they do brutally and realistically illustrate scenes of sexual assault between characters.[77]

Tragedy

Juné stories with suicide endings were popular,[78] as was "watching men suffer".[79] Rachel Thorn theorizes that depicting abuse in yaoi is a way for some readers of yaoi to "come to terms with their own experiences of abuse".[8] By the mid-1990s the fashion was for happy endings.[78] When tragic endings are shown, the cause is not infidelity, but "the cruel and intrusive demands of an uncompromising outside world".[80]

Publishing

Japan

As of 1990, seven Japanese publishers included BL content in their offerings, which kickstarted the commercial publishing market of the genre.[46] By 2003, 3.8% of weekly manga magazines were dedicated to BL.[3] A 2008 assessment estimated that the Japanese commercial yaoi market grossed approximately 12 billion yen annually, with novel sales generating 250 million yen per month, manga generating 400 million yen per month, CDs generating 180 million yen per month, and video games generating 160 million yen per month. As of this time, magazines for BL included BE-BOY, GUSH, CHARA and CIEL.[81] A 2010 report estimated that the yaoi market was worth approximately 21.3 billion yen in both 2009 and 2010.[82]

Besides manga and anime, there are also boys' love (BL) games (also known as yaoi games), usually consisting of visual novels or H games oriented around male homosexual couples for the female market. The defining factor is that both the playable character(s) and possible objects of affection are male. As with yaoi manga, the major market is assumed to be female. Games aimed at a homosexual male audience may be referred to as bara. A 2006 breakdown of the Japanese commercial BL market estimated it grosses approximately 12 billion yen annually, with video games generating 160 million yen per month.[81]

English-speaking countries

Yaoi manga are sold to English-speaking countries by companies that translate and print them in English. Companies such as Digital Manga Publishing with their imprints 801 Media (for explicit yaoi) and Juné (for "romantic and sweet" yaoi),[34] as well as Kitty Media, and Viz Media under their imprint SuBLime. Companies that formerly published yaoi manga but are now defunct include DramaQueen, Central Park Media's Be Beautiful,[21] Tokyopop under their BLU imprint, Broccoli under their Boysenberry imprint, and Aurora Publishing under their Deux Press imprint. Yaoi Press, based in Las Vegas and specializing in yaoi that is not of Japanese origin, remains active. According to McLelland, the earliest officially translated English-language yaoi manga was printed in 2003, and as of 2006 there were about 130 English-translated works commercially available.[83] In March 2007, Media Blasters stopped selling shōnen manga and increased their yaoi lines in anticipation of publishing one or two titles per month that year.[84]

Among the 135 yaoi manga published in North America between 2003 and 2006, 14% were rated for readers aged 13 years or over, 39% were rated for readers aged 15 or older, and 47% were rated for readers age 18 and up.[85] Although American booksellers were increasingly stocking yaoi titles in 2008, their restrictions led publishers to label books conservatively, often rating books originally intended for a mid-teen readership as 18+ and distributing them in shrinkwrap.[31] Diamond Comic Distributors valued the sales of yaoi manga in the United States at approximately $US six million in 2007.[86] By December 2007, there were over 10 publishers in North America offering yaoi materials.[87]

Only a select few yaoi games have been officially translated into English. In 2006, JAST USA announced they would be releasing Enzai as Enzai: Falsely Accused, the first license of a yaoi game in English translation.[88] Some fan communities have criticized the choice of such a dark and unromantic game as the US market's first exposure to the genre. JAST USA subsequently licensed Zettai Fukujuu Meirei under the title Absolute Obedience,[89] while Hirameki International licensed Animamundi; the later game, although already nonexplicit, was censored for US release to achieve a "mature" rather than "adults only" rating, removing some of both the sexual and the violent content.[90] The lack of interest by publishers in licensing further titles has been attributed to widespread copyright infringement of both licensed and unlicensed games.[91]

Marketing was significant in the transnational travel of yaoi from Japan to United States. Due to earlier marketing efforts by distributors, yaoi has attracted a following of gay male fans in the United States. Kizuna (1994) was described by Phoenix-based distributor Ariztical Entertainment that specializes in LGBT films as "the first gay male anime to be released on DVD in the US" to market it to the gay male audience.[92] Furthermore, a review of Kizuna was ran in an issue of the prominent American LGBT magazine The Advocate, released on 4 February 1997. The review, written by Cathay Che, noted that Kizuna was "the first shōnen-ai animated series ... distributed by mail order through the gay-owned company Phoenix Distributors."[93] Che also described the two-episode OVA series to be "as accessible as the usual gay art house film is eccentric and experimental", tying the animated series to the larger gay media library.[93]

Fan fiction

The Japanese fan fiction (dōjinshi) subculture emerged contemporaneously with its English equivalent in the 1970s.[34][62] Characteristic similarities of fan fiction in both countries include non-adherence to a standard "narrative structure" and a particular popularity of science fiction themes.[14] The early yaoi dōjinshi were amateur publications not controlled by media restrictions. The stories were written by teenagers for an adolescent audience and were generally based on manga or anime characters who were likewise in their teens or early twenties.[62] Most dōjinshi are created by amateurs who often work in "circles".[94] The group CLAMP began as an amateur dōjinshi circle who worked together to create Saint Seiya parodies.[95] Certain professional artists such as Kodaka Kazuma also create dōjinshi.[96] Some publishing companies reviewed dōjinshi manga published in the 1980s to identify talented amateurs,[34] leading to the discovery of Youka Nitta and numerous other artists.[97] This practice lessened in the 1990s, but was still used to find Shungiku Nakamura.[17]

Typical yaoi dōjinshi features male-male pairings from non-romantic manga and anime. Much of the material derives from male-oriented shōnen and seinen works which contain close male-male friendships and are perceived by fans to imply elements of homoeroticism,[8] such as with Captain Tsubasa[13] and Saint Seiya, two titles which popularized yaoi in the 1980s.[62] Weekly Shonen Jump is known to have a large female readership who engage in yaoi readings.[98] Publishers of shōnen manga may create "homoerotic-themed" merchandise as fan service to their BL fans.[99] Comiket's co-founder Yoshihiro Yonezawa described dōjinshi as akin to "girls playing with dolls";[43] yaoi fans may ship any male-male pairing, sometimes pairing off a favourite character, or creating a story about two original male characters and incorporating established characters into the story.[13] Any male character may become the subject of a yaoi dōjinshi, including characters from non-manga titles such as Harry Potter or The Lord of the Rings,[100] video games such as Kingdom Hearts Overwatch and Final Fantasy,[101][102] or real people such as politicians. Amateur authors may also create characters out of personifications of abstract concepts (such as the personification of countries in Hetalia: Axis Powers) or complementary objects like salt and pepper.[103] In Japan, the labelling of yaoi dōjinshi is typically composed of the two lead characters' names, separated by a multiplication sign, with the seme being first and the uke being second.[104]

While Gundam Wing does not have explicit gay romance content, its first airing in North America via Cartoon Network in 2000, five years after its initial broadcast in Japan, was crucial to Western fan creation of yaoi fiction, as noted by McHarry in his article that performs a reading of "Western yaoi story" with ideas of gender theorists such as Judith Butler and Eve Sedgewick.[105] As yaoi fanfiction has so often been compared to the Western fan practice of slash, it is important to understand the subtle differences between them. Levi notes that "the youthful teen look that so easily translates into androgyny in boys' love manga, and allows for so many layered interpretations of sex and gender, is much harder for slash writers to achieve."[106] Regardless, the similarities and connections between yaoi and slash fan fictions should not be overlooked given the profound intersections between the two fan subcultures, as revealed by the multitude of Harry Potter-inspired slash fictions and dojinshi.

Yaoi-inspired works outside Japan

As yaoi gained popularity in the United States, a few American artists began creating original English-language manga for female readers featuring male-male couples referred to as "American yaoi". The first known original English-language yaoi comic is Sexual Espionage #1 by Daria McGrain, published in May 2002.[107] Since approximately 2004, what started as a small subculture in North America has become a burgeoning market, as new publishers began producing female-oriented male-male erotic comics and manga from creators outside Japan.[108] Because creators from all parts of the globe are published in these works, the term "American yaoi" fell out of use and were replaced by terms like "original English language yaoi"[109] and "Global Yaoi".[110]

The term "Global Yaoi" or "Global BL" was coined by creators and newsgroups that wanted to distinguish the Asian specific content known as yaoi, from the original English content.[111][112] Global BL was shortened by comics author Tina Anderson in interviews and on her blog to the acronym "GloBL".[113] High-Volume North American publishers of Global BL are Yaoi Press,[114] which continues to release illustrated fiction written by the companies CEO, Yamila Abraham under the imprint Yaoi Prose.[115] Prior publishers include DramaQueen, which debuted its Global BL quarterly anthology RUSH in 2006,[116] and Iris Print,[117] both ceased publishing due to financial issues.[118] In 2015, "Tweek x Craig", a season 19 episode of the American animation series South Park, centered upon the eponymous characters objecting to being depicted by their female schoolmates in yaoi-themed illustrations.

In 2009, Germany saw a period of GloBL releases, with a handful of original German titles gaining popularity for being set in Asia.[119] Some publishers of German GloBL were traditional manga publishers like Carlsen Manga,[120] and small press publishers specializing in GloBL like The Wild Side[121] and Fireangels Verlag.[122]

Other successful series in GloBL include web comics Teahouse, Starfighter, Purpurea Noxa, and In These Words from artist Jo Chen's studio Guilt Pleasure, all three of which were also promoted by Digital Manga Publishing.[123]

Yaoi is known as danmei (耽美), which is the Mandarin reading of the Japanese term tanbi, in Sinophone contexts. The first appearance of danmei in China could be traced back to 1998 under the influence of yaoi culture.[124] However, state regulations in China make it difficult for danmei writers to publish their works online. In January 2009, the National Publishing Administration of China updated its third list of banned online fiction, most of which was danmei fiction.[125] In 2014, Anhui TV reported that at least 20 young female authors writing danmei novels on an online novel website were arrested.[126] In 2018, a female author received a ten-year and six-month prison sentence for breaking obscenity laws in China by selling her danmei novel Gongzhan (攻占) on Taobao, China's largest online shopping website.[127]

Demographics

Most yaoi fans are either teenage girls or young women. In Thailand, female readership of yaoi works is estimated at 80%,[128] and the membership of Yaoi-Con, a yaoi convention in San Francisco, is 85% female. It is usually assumed that all female fans are heterosexual, but in Japan there is a presence of lesbian manga authors[15] and lesbian, bisexual or questioning female readers.[129] Recent online surveys of English-speaking readers of yaoi indicate that 50-60% of female readers self-identify as heterosexual.[130]

Although the genre is marketed to girls and women, there is a gay,[83] bisexual,[131] and heterosexual male[132][133][134] readership as well. A survey of yaoi readers among patrons of a United States library found about one quarter of respondents were male;[135] two online surveys found approximately ten percent of the broader English-speaking yaoi readership were male.[31][130]

Lunsing suggests that younger Japanese gay men who are offended by "pornographic" content in gay men's magazines may prefer to read yaoi instead.[136] Some gay men, however, are put off by the feminine art style or unrealistic depictions of LGBT culture in Japan and instead prefer gei comi,[15] which some perceive to be more realistic.[13] Lunsing notes that some of the yaoi narrative elements criticized by homosexual men, such as rape fantasies, misogyny, and characters' non-identification as gay, are also present in gei comi.[15]

In the mid-1990s, estimates of the size of the Japanese yaoi fandom ranged from 100,000 to 500,000 people.[15] At around that time, June magazine had a circulation of between 80,000 and 100,000, twice the circulation of the best selling gay lifestyle magazine Badi. As of April 2005, a search for non-Japanese websites resulted in 785,000 English, 49,000 Spanish, 22,400 Korean, 11,900 Italian, and 6,900 Chinese sites.[47] In January 2007, there were approximately five million hits for yaoi.[137]

A large portion of Western fans choose to pirate yaoi material because they are unable or unwilling to obtain it through sanctioned methods. For example, fans may lack a credit card for payment, or they may want to keep their yaoi private because of the dual stigma of seeking sexually explicit material which is also gay. Scanlations and other fan translation efforts are common.[138] In addition to commercially published Japanese works, amateur dojinshi may be scanlated into English.[139]

Critical reception

General

Boys' love manga has received considerable critical attention, especially after translations of BL became commercially available outside Japan in the 21st century.[8] Different critics and commentators have had very different views of BL. In 1983, Frederik L. Schodt, an American writer and translator, observed that portrayals of gay male relationships had used and further developed bisexual themes already in existence in shōjo manga to appeal to their female audience.[140] Japanese critics have viewed boys' love as a genre that permits their audience to avoid adult female sexuality by distancing sex from their own bodies,[141] as well as to create fluidity in perceptions of gender and sexuality and rejects "socially mandated" gender roles as a "first step toward feminism".[142] Kazuko Suzuki, for example, believes that the audience's aversion to or contempt for masculine heterosexism is something which has consciously emerged as a result of the genre's popularity.[143]

Mizoguchi, writing in 2003, feels that BL is a "female-gendered space", as the writers, readers, artists and most of the editors of BL are female.[20] BL has been compared to romance novels by English-speaking librarians.[40][71] Parallels have also been noted in the popularity of lesbianism in pornography,[43][83] and yaoi has been called a form of "female fetishism".[144] Mariko Ōhara, a science fiction writer, has said that she wrote yaoi Kirk/Spock fiction as a teen because she could not enjoy "conventional pornography, which had been made for men", and that she had found a "limitless freedom" in yaoi, much like in science fiction.[145]

Other commentators have suggested that more radical gender-political issues underlie BL. In 1998, Shihomi Sakakibara argued that yaoi fans, including himself, were gay female-to-male transsexuals.[146] Sandra Buckley believes that bishōnen narratives champion "the imagined potentialities of alternative [gender] differentiations",[147] while James Welker described the bishōnen character as "queer", commenting that manga critic Akiko Mizoguchi saw shōnen-ai as playing a role in how she herself had become a lesbian.[148] Dru Pagliassotti sees this and the yaoi ronsō as indicating that for Japanese gay and lesbian readers, BL is not as far removed from reality as heterosexual female readers like to claim.[31] Welker has also written that boys' love titles liberate the female audience "not just from patriarchy, but from gender dualism and heteronormativity".[148]

Criticism

Some gay and lesbian commentators have criticized how gay identity is portrayed in BL, most notably in the yaoi ronsō or "yaoi debate" of 1992–1997.[15][30] A trope of yaoi that has attracted criticism is male protagonists who do not identify as gay, but are rather simply in love with each other. This is said to heighten the theme of all-conquering love,[56] but is also condemned for avoiding the need to address prejudices against people who state that they were born gay, lesbian or bisexual.[149] Yaoi stories (such as 1987's Tomoi[15] and 1996–1998's[150] New York, New York) have increasingly featured characters that identify as gay.[15] Criticism of the stereotypically "girly" behaviour of the uke has also been prominent.[45]

Japanese gay activist Masaki Satou criticized yaoi fans and artists in an open letter to the feminist zine Choisir in May 1992, writing that the genre was lacking in any accurate information about gay men and conveniently avoided the very real prejudice and discrimination that gay men faced as a part of society. More significantly, its portrayal of gay men as wealthy, handsome, and well-educated was simply a vehicle for heterosexual female masturbation fantasies.[15][30] An extensive debate ensued, with yaoi fans and artists arguing that yaoi is entertainment for women, not education for gay men, and that yaoi characters are not meant to represent "real gay men".[30] As Internet resources for gay men developed in the 1990s, the yaoi debate waned[151] but occasionally resurfaced; for example, when Mizoguchi in 2003 characterized stereotypes in modern BL as being "unrealistic and homophobic".[152]

There has been similar criticism to the Japanese yaoi debate in the English-speaking fandom.[44][153][154][155] In 1993 and 2004, Rachel Thorn pointed to the complexity of these phenomena, and suggested that yaoi and slash fiction fans are discontented with "the standards of femininity to which they are expected to adhere and a social environment that does not validate or sympathize with that discontent".[8][156]

In China, BL became very popular in the late 1990s, attracting media attention, which became negative, focusing on the challenge it posed to "heterosexual hegemony". Publishing and distributing BL is illegal in mainland China.[157] Zanghellini notes that due to the "characteristics of the yaoi/BL genre" of showing characters who are often underage engaging in romantic and sexual situations, child pornography laws in Australia and Canada "may lend themselves to targeting yaoi/BL work". He notes that in the UK, cartoons are exempt from child pornography laws unless they are used for child grooming.[39]

In 2001, a controversy erupted in Thailand regarding gay male comics. Television reports labelled the comics as negative influences, while a newspaper falsely stated that most of the comics were not copyrighted as the publishers feared arrest for posting the content; in reality most of the titles were likely illegally published without permission from the original Japanese publishers. The shōnen-ai comics provided profits for the comic shops, which sold between 30 and 50 such comics per day. The moral panic regarding the gay male comics subsided. The Thai girls felt too embarrassed to read heterosexual stories, so they read gay male-themed josei and shōjo stories, which they saw as "unthreatening".[158]

Youka Nitta has said that "even in Japan, reading boys' love isn't something that parents encourage" and encouraged any parents who had concerns about her works to read them.[159] Although in Japan, concern about manga has been mostly directed to shōnen manga, in 2006, an email campaign was launched against the availability of BL manga in Sakai City's public library. In August 2008, the library decided to stop buying more BL, and to keep its existing BL in a collection restricted to adult readers. That November, the library was contacted by people who protested against the removal, regarding it as "a form of sexual discrimination". The Japanese media ran stories on how much BL was in public libraries, and emphasised that this sexual material had been loaned out to minors. Debate ensued on Mixi, a Japanese social networking site, and the library would return its BL to the public collection. Mark McLelland suggests that BL may become "a major battlefront for proponents and detractors of 'gender free' policies in employment, education and elsewhere".[160]

In 2010, the Osaka Prefectural Government included boys' love manga among with other books deemed potentially "harmful to minors" due to its sexual content,[161] which resulted in several magazines prohibited from being sold to people under 18 years of age.[162] Boys' love content was initially not included in the raid due to the officials claiming that the books only interested a small, niche demographic.[162]

See also

Notes

- Initially called aniparo, this term covered both male fans' work about female characters and female fans' work about male characters, but yaoi would be surpassed by aniparo as referring to women's fictions.[3]

- First serialized in Shōjo Comic in January 1976, Kaze to Ki no Uta has been called "the first commercially published boys' love story",[6] but this claim has been challenged, as the first male-male kiss was in the 1970 manga In the Sunroom, also by Takemiya.[7] Rachel Thorn says that Kaze was "the first shōjo manga to portray romantic and sexual relationships between boys", and that Takemiya first thought of Kaze nine years before it was approved for publication. Takemiya attributes the gap between the idea and its publication to the sexual elements of the story.[8]

- This character has been called an osoi uke ("attacking uke"). He is usually paired with a hetare seme ("wimpy seme").[48]

References

- Welker, James (28 January 2015), "A Brief History of Shōnen'ai, Yaoi, and Boys Love", Boys Love Manga and Beyond, University Press of Mississippi, pp. 42–75, doi:10.14325/mississippi/9781628461190.003.0003, ISBN 9781628461190

- Welker, James (2015). "A History of Shonen'ai, Yaoi, and Boys Love". Boys' love manga and beyond : history, culture, and community in Japan. McLelland, Mark J., 1966-, Nagaike, Kazumi,, Suganuma, Katsuhiko,, Welker, James. Jackson. ISBN 9781628461206. OCLC 885378169.

- Galbraith, Patrick W. (2011). "Fujoshi: Fantasy Play and Transgressive Intimacy among "Rotten Girls" in Contemporary Japan". Signs. 37 (1): 211–232. doi:10.1086/660182.

- "Definitions From Japan: BL, Yaoi, June". aestheticism.com. Archived from the original on 5 June 2009.

- Thorn, Rachel Matt What Shôjo Manga Are and Are Not – A Quick Guide for the Confused Archived 18 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Toku, Masami (2007) "Shojo Manga! Girls’ Comics! A Mirror of Girls’ Dreams Archived 15 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine" Mechademia 2 p. 27

- Journalista – the news weblog of The Comics Journal " Blog Archive " 27 Mar. 2007: The first draft of history (some revisions may be necessary).Tcj.com. Retrieved on 23 December 2008

- Thorn, Rachel Matt. (2004) "Girls And Women Getting Out Of Hand: The Pleasure And Politics Of Japan's Amateur Comics Community." pp. 169–186, In Fanning the Flames: Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan, William W. Kelly, ed., State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-6032-0. Retrieved 12 August 2008.

- Matsui, Midori. (1993) "Little girls were little boys: Displaced Femininity in the representation of homosexuality in Japanese girls' comics," in Gunew, S. and Yeatman, A. (eds.) Feminism and The Politics of Difference, pp. 177–196. Halifax: Fernwood Publishing.

- Kotani Mari, foreword to Saitō Tamaki (2007) "Otaku Sexuality" in Christopher Bolton, Istvan Csicsery-Ronay Jr., and Takayuki Tatsumi ed., page 223 Robot Ghosts and Wired Dreams University of Minnesota Press ISBN 978-0-8166-4974-7

- Ingulsrud, John E.; Allen, Kate (2009). Reading Japan Cool: Patterns of Manga Literacy and Discourse. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-7391-2753-7.

- Suzuki, Kazuko. 1999. "Pornography or Therapy? Japanese Girls Creating the Yaoi Phenomenon". In Sherrie Inness, ed., Millennium Girls: Today's Girls Around the World. London: Rowman & Littlefield, p. 252 ISBN 0-8476-9136-5, ISBN 0-8476-9137-3.

- Wilson, Brent; Toku, Masami. "Boys' Love", Yaoi, and Art Education: Issues of Power and Pedagogy Archived 10 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine 2003

- Kinsella, Sharon Japanese Subculture in the 1990s: Otaku and the Amateur Manga Movement Journal of Japanese Studies, Vol. 24, No. 2 (Summer, 1998), pp. 289–316

- Lunsing, Wim. Yaoi Ronsō: Discussing Depictions of Male Homosexuality in Japanese Girls' Comics, Gay Comics and Gay Pornography Archived 10 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context Issue 12, January 2006 Accessed 12 August 2008.

- Fujimoto, Yukari (1991) "Shōjo manga ni okeru 'shōnen ai' no imi" ("The Meaning of 'Boys' Love' in Shōjo Manga"). In N. Mizuta, ed. New Feminism Review, Vol. 2: Onna to hyōgen ("Women and Expression"). Tokyo: Gakuyō Shobō, ISBN 4-313-84042-7. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) (in Japanese). Accessed 12 August 2008. "やめ て、お尻が、いたいから" – "Stop, because my butt hurts"

- Bollmann, T. (2010). He-romance for her – yaoi, BL and shounen-ai. Archived 19 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine In E. Niskanen (Ed.), Imaginary Japan: Japanese Fantasy in Contemporary Popular Culture (pp.42-46). Turku: International Institute

- "ICv2 - Digital Manga Names New Yaoi Imprint". ICV2. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- Wei, John (2014). "Queer encounters between Iron Man and Chinese boys' love fandom". Transformative Works and Cultures. 17. doi:10.3983/twc.2014.0561.

- Akiko, Mizoguchi (2003). "Male-Male Romance by and for Women in Japan: A History and the Subgenres of Yaoi Fictions". U.S.-Japan Women's Journal. 25: 49–75.

- Jones, V. E. "He Loves Him, She Loves Them: Japanese comics about gay men are increasingly popular among women" Archived 2 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Boston.com. April 2005.

- Thompson, David (8 September 2003). "Hello boys". New Statesman. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Aquila, Meredith (2007) "Ranma 1/2 Fan Fiction Writers: New Narrative Themes or the Same Old Story? Archived 15 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine" Mechademia 2 p.39

- Aoyama, Tomoko (April 2009). "Eureka Discovers Culture Girls, Fujoshi, and BL: Essay Review of Three Issues of the Japanese Literary magazine, Yuriika (Eureka)". Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific. 20. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- "Tonari no 801 chan Fujoshi Manga Adapted for Shōjo Mag". Archived from the original on 19 January 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- Welker, James (2006). "Beautiful, Borrowed, and Bent: 'Boys' Love' as Girls' Love in Shôjo Manga'". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 31 (3): 842. doi:10.1086/498987.

- Suzuki, Kazuko. 1999. "Pornography or Therapy? Japanese Girls Creating the Yaoi Phenomenon". In Sherrie Inness, ed., Millennium Girls: Today's Girls Around the World. London: Rowman & Littlefield, p.250 ISBN 0-8476-9136-5, ISBN 0-8476-9137-3.

- Angles, Jeffrey (2011). Writing the love of boys : origins of Bishōnen culture in modernist Japanese literature. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8166-6970-7.

- Welker, James. "Intersections: Review, Boys' Love Manga: Essays on the Sexual Ambiguity and Cross-Cultural Fandom of the Genre". Intersections. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- Vincent, Keith (2007) "A Japanese Electra and Her Queer Progeny Archived 15 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine" Mechademia 2 pp. 64–79

- Pagliassotti, Dru (November 2008) 'Reading Boys' Love in the West' Archived 1 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine Particip@tions Volume 5, Issue 2 Special Edition

- Bauer, Carola (2013). Naughty girls and gay male romance/porn : slash fiction, boys' love manga, and other works by Female "Cross-Voyeurs" in the U.S. Academic Discourses. [S.l.]: Anchor Academic Publishing. p. 81. ISBN 978-3954890019.

- Suzuki, Kazuko. 1999. "Pornography or Therapy? Japanese Girls Creating the Yaoi Phenomenon". In Sherrie Inness, ed., Millennium Girls: Today's Girls Around the World. London: Rowman & Littlefield, p.251 ISBN 0-8476-9136-5, ISBN 0-8476-9137-3.

- Strickland, Elizabeth. "Drawn Together." Archived 20 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine The Village Voice. 2 November 2006.

- Cha, Kai-Ming (7 March 2005). "Yaoi Manga: What Girls Like?". Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on 4 December 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Wood, Andrea (2006). "Straight" Women, Queer Texts: Boy-Love Manga and the Rise of a Global Counterpublic". WSQ: Women's Studies Quarterly. 34 (1/2): 394–414.

- Aoki, Deb (3 March 2007) Interview: Erica Friedman – Page 2 Archived 21 June 2013 at WebCite "Because the dynamic of the seme/uke is so well known, it's bound to show up in yuri. ... In general, I'm going to say no. There is much less obsession with pursued/pursuer in yuri manga than there is in yaoi."

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 June 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Zanghellini, A. (2009). "Underage Sex and Romance in Japanese Homoerotic Manga and Anime". Social & Legal Studies. 18 (2): 159–177. doi:10.1177/0964663909103623.

- Camper, Cathy (2006) Yaoi 101: Girls Love "Boys' Love".

- Suzuki, Kazuko. 1999. "Pornography or Therapy? Japanese Girls Creating the Yaoi Phenomenon". In Sherrie Inness, ed., Millennium Girls: Today's Girls Around the World. London: Rowman & Littlefield, p. 253 ISBN 0-8476-9136-5, ISBN 0-8476-9137-3.

- Sihombing, Febriani (2011). "On The Iconic Difference between Couple Characters in Boys Love Manga Archived 21 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine". Image & Narrative 12 (1)

- Avila, K. "Boy's Love and Yaoi Revisited" Archived 12 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Sequential Tart. January 2005.

- Masaki, Lyle. (6 January 2008) "Yowie!": The Stateside appeal of boy-meets-boy YAOI comics Archived 17 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine AfterElton.com

- Keller, Katherine Seme and Uke? Make Me Puke Archived 14 September 2012 at Archive.today Sequential Tart February 2008

- Bauer, Carola (2013). Naughty girls and gay male romance/porn : slash fiction, boys' love manga, and other works by Female "Cross-Voyeurs" in the U.S. Academic Discourses. [S.l.]: Anchor Academic Publishing. p. 82. ISBN 978-3954890019.

- McLelland, Mark. The World of Yaoi: The Internet, Censorship and the Global "Boys' Love" Fandom Archived 19 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Australian Feminist Law Journal, 2005.

- "fujyoshi.jp". Archived from the original on 5 August 2008.

- Manry, Gia. (16 April 2008) It's A Yaoi Thing: Boys Who Love Boys and the Women Who Love Them Archived 9 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine The Escapist

- McLelland, Mark (2000). Male homosexuality in modern Japan. Routledge. pp. 131, ff. ISBN 978-0-7007-1300-4.

- Dirk Deppey. "A Comics Reader's Guide to Manga Scanlations". The Comics Journal. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- Elfodiluce, Valeriano (12 April 2004). "L'altra faccia dei manga gay". Gay.it. Archived from the original on 25 May 2014. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- McLelland, Mark (2000). Male homosexuality in modern Japan. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-7007-1300-4.

- Simona (13 May 2009). "Simona's BL Research Lab: Reibun Ike, Hyogo Kijima, Inaki Matsumoto". Akibanana. Archived from the original on 3 October 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- Anderson, Tina. "That Damn Bara Article!". Guns, Guys & Yaoi. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- Lees, Sharon (June 2006). "Yaoi and Boys' Love" Archived 2 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Akiba Angels.

- Fletcher, Dani (May 2002). Guys on Guys for Girls – Yaoi and Shounen Ai Archived 26 December 2005 at the Wayback Machine. Sequential Tart.

- Suzuki, Kazuko. 1999. "Pornography or Therapy? Japanese Girls Creating the Yaoi Phenomenon". In Sherrie Inness, ed., Millennium Girls: Today's Girls Around the World. London: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 259–260 ISBN 0-8476-9136-5, ISBN 0-8476-9137-3.

- Saitō Tamaki (2007) "Otaku Sexuality" in Christopher Bolton, Istvan Csicsery-Ronay Jr., and Takayuki Tatsumi ed., p. 231 Robot Ghosts and Wired Dreams University of Minnesota Press ISBN 978-0-8166-4974-7

- Drazen, Patrick (October 2002). '"A Very Pure Thing": Gay and Pseudo-Gay Themes' in Anime Explosion! The What, Why & Wow of Japanese Animation Berkeley, California: Stone Bridge Press p. 95 ISBN 1-880656-72-8. "The five pilots of Gundam Wing (1995) have female counterparts, yet a lot of fan sites are produced as if these girls never existed."

- Fujimoto, Yukari (2013). Berndt, Jaqueline; Kümmerling-Meibauer, Bettina (eds.). Manga's cultural crossroads. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 184. ISBN 978-1134102839.

- McHarry, Mark (November 2003). "Yaoi: Redrawing Male Love". The Guide. Archived from the original on 17 April 2008.

- Fermin, Tricia Abigail Santos (2013). "Appropriating Yaoi and Boys Love in the Philippines: Conflict, Resistance and Imaginations Through and Beyond Japan". Ejcjs. 13 (3). Archived from the original on 31 December 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Mayerson, Ginger (1 April 2007). "Ichigenme Volume 1". The Report Card. Sequential Tart. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2009.

- Kazumi, Nagaike (2003). "Perverse Sexualities, Perverse Desires: Representations of Female Fantasies and Yaoi Manga as Pornography Directed at Women". U.S.-Japan Women's Journal. 25: 76–103.

- McHarry, Mark. (2006) "Yaoi" in Gaëtan Brulotte and John Phillips (eds.). Encyclopedia of Erotic Literature. New York: Routledge, pp. 1445–1447.

- Mizoguchi, Akiko (September 2010). "Theorizing comics/manga genre as a productive forum: yaoi and beyond" (PDF). In Berndt, Jaqueline (ed.). Comics Worlds and the World of Comics: Towards Scholarship on a Global Scale. Kyoto, Japan: International Manga Research Center, Kyoto Seika University. pp. 145–170. ISBN 978-4-905187-01-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 29 October 2010.

- Salek, Rebecca (June 2005) More Than Just Mommy and Daddy: "Nontraditional" Families in Comics Archived 2 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine Sequential Tart

- de Bats, Hadrien (2008). "Entretien avec Hisako Miyoshi". In Brient, Hervé (ed.). Homosexualité et manga: le yaoi. Manga: 10000 images (in French). Editions H. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-2-9531781-0-4.

- Shamoon, Deborah (July 2004) "Office Sluts and Rebel Flowers: The Pleasures of Japanese Pornographic Comics for Women" in Linda Williams ed. Porn Studies. Duke University Press p. 86

- Brenner, Robin (15 September 2007). "Romance by Any Other Name". Library Journal. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Wildsmith, Snow. "Yaoi Love: An Interview with Makoto Tateno". Graphic Novel Reporter. Archived from the original on 28 November 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- "Intersections: Rethinking Yaoi on the Regional and Global Scale". Archived from the original on 26 May 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- Suzuki, Kazuko. 1999. "Pornography or Therapy? Japanese Girls Creating the Yaoi Phenomenon". In Sherrie Inness, ed., Millennium Girls: Today's Girls Around the World. London: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 257–258 ISBN 0-8476-9136-5, ISBN 0-8476-9137-3.

- Valenti, Kristy L. (July 2005). ""Stop, My Butt Hurts!" The Yaoi Invasion". The Comics Journal (269). Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Under Grand Hotel Vol. #01 - Mania.com

- Frennea, Melissa. (2012). "Forbidden Love and Violent Desire: Themes in the WWII Yaoi Manga of Fusanosuke Inariya" Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Presented at the Popular Culture Association Conference 2012 in Boston, MA.

- Schodt, Frederik L. (1996) Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga pp. 120–123

- Gravett, Paul (2004) Manga: 60 Years of Japanese Comics (Harper Design ISBN 1-85669-391-0) pp. 80–81

- McLelland, Mark (2000) "The love between 'beautiful boys' in women's comics" p. 69 Male Homosexuality in Modern Japan: Cultural Myths and Social Realities Richmond, Surrey: Curzon Press ISBN 0-7007-1425-1

- Nagaike, Kazumi (April 2009). "Elegant Caucasians, Amorous Arabs, and Invisible Others: Signs and Images of Foreigners in Japanese BL Manga". Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific (20). Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- "Yano Research Reports on Japan's 2009-10 Otaku Market - News - Anime News Network". Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- McLelland, Mark. Why are Japanese Girls' Comics full of Boys Bonking? Archived 15 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine Refractory: A Journal of Entertainment Media Vol.10, 2006/2007

- Cha, Kai-Ming (13 March 2007) Media Blasters Drops Shonen; Adds Yaoi Archived 24 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine Publishers Weekly

- McLelland, Mark; Yoo, Seunghyun (2007). "The International Yaoi Boys' Love Fandom and the Regulation of Virtual Child Pornography: The Implications of Current Legislation". Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 4 (1): 93–104. doi:10.1525/srsp.2007.4.1.93. Archived from the original on 27 August 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- Cha, Kai-Ming (10 August 2008) Brokeback comics craze Archived 18 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine San Francisco Chronicle

- Butcher, Christopher (11 December 2007). "Queer love manga style" Archived 4 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Xtra!.

- "JAST USA Announces First "Boy's Love" PC Dating-Game". Anime News Network. 16 January 2006. Archived from the original on 14 October 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "JAST USA Announces Adult PC Game "Absolute Obedience" Ships, Also Price Reduction". ComiPress. 25 October 2006. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- Wiggle. "Anima Mundi: Dark Alchemist Review". Boys on Boys on Film. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- Abraham, Yamilla (22 August 2008). "Yaoi Computer Games Nil". Yaoi Press. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "Ariztical Entertainment | About Us". www.ariztical.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- Che, Cathay. "Catoon Comes Out: Kizuna Volume 1 and 2." The Advocate 726. 4 February 1997: p. 66.

- Ishikawa, Yu (2008) Yaoi: Fan Art in Japan Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine (PDF) in Compilation of papers and seminar proceedings - Comparative Studies on Urban Cultures, 17–19 September 2008, Osaka City University, pp.37-42 The International School Office, Graduate School of Literature and Human Sciences, Osaka City University. Accessed 9 December 2014.

- Kimbergt, Sébastien (2008). "Ces mangas qui utilisent le yaoi pour doper leurs ventes". In Brient, Hervé (ed.). Homosexualité et manga: le yaoi. Manga: 10000 images (in French). Editions H. pp. 113–115. ISBN 978-2-9531781-0-4.

- Lees Sharon-Ann (July 2006). "Yaoi Publishers Interviews: Part 3 - Be Beautiful". Akiba Angels. Archived from the original on 9 September 2006. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- O'Connell, M. "Embracing Yaoi Manga: Youka Nitta" Archived 27 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Sequential Tart. April 2006.

- Fujimoto, Yukari (2013). Berndt, Jaqueline; Kümmerling-Meibauer, Bettina (eds.). Manga's cultural crossroads. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. p. 172. ISBN 978-1134102839.

- McHarry, Mark (2011). (Un)gendering the homoerotic body: Imagining subjects in boys' love and yaoi Archived 21 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Transformative Works and Cultures

- Granick, Jennifer (16 August 2006) Harry Potter Loves Malfoy Archived 13 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Wired.com

- Kingdom Hearts aestheticism.com

- Burn, Andrew; Schott, Gareth (2004). "Heavy Hero or Digital Dummy? Multimodal Player–Avatar Relations in Final Fantasy 7" (PDF). Visual Communication. 3 (2): 213–233. doi:10.1177/147035704043041. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 November 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- Galbraith, Patrick W. (31 October 2009) Moe: Exploring Virtual Potential in Post-Millennial Japan Archived 21 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Toku, Masami (6 June 2002) Interview with Mr. Sagawa Archived 11 August 2011 at WebCite

- McHarry, Mark. "Identity Unmoored: Yaoi in the West." Queer Popular Culture: Literature, Media, Film and Television, ed. Thomas Peele. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007, p. 193.

- Levi, Antonia. "Introduction." Boy’s Love Manga: Essays on the Sexual Ambiguity and Cross-Cultural Fandom of the Genre, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc. Publishers, 2008, p. 3.

- Pagliassotti, Dru (2 June 2008) Yaoi Timeline: Spread Through U.S.

- "The Growth of Yaoi". Archived from the original on 20 February 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- Arrant, Chris (6 June 2006). "Home-Grown Boys' Love from Yaoi Press". Archived from the original on 16 June 2006. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Abraham, Yamila (April 2007). "Publisher Yaoi Press 'Global Yaoi' Amazon Listings". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- "Links to Yaoi-Con coverage". 29 October 2007. Archived from the original on 17 October 2011.

- "German Publisher Licenses Global BL Titles". April 2008. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011. Retrieved 14 July 2008.

- "GloBL Previews and Other Stuff". September 2007. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012.

- "Yaoi Press Moves Stores and Opens Doors". Archived from the original on 9 November 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- "Interview: Yamila Abraham". Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- "DramaQueen Announces New Yaoi & Manhwa Titles". Archived from the original on 20 August 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2007.

- "A Year of Yaoi At Iris Print". Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 13 March 2007.

- "Iris Print Wilts". Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- Malone, Paul M. (April 2009). "Home-grown Shōjo Manga and the Rise of Boys' Love among Germany's 'Forty-Niners'". Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific. 20. Archived from the original on 1 March 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2012.

- "Anne Delseit, Martina Peters". Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- "The Wildside Verlag Blog". Archived from the original on 29 July 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- "Fireangels.net Site". Archived from the original on 30 August 2016. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- "Sleepless Nights, In These Words – New BL Titles Scheduled For Print". Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- Xu, Yanrui, and Ling Yang. "Forbidden love: incest, generational conflict, and the erotics of power in Chinese BL fiction." Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 4 no. 1, 2013. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21504857.2013.771378

- Liu, Ting. "Conflicting Discourses on Boys' Love and Subcultural Tactics in Mainland China and Hong Kong." Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific 20, April 2009. http://intersections.anu.edu.au/issue20/liu.htm Archived 28 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "天天故事会:神秘写手落网记[超级新闻场]". v.youku.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- "Woman Receives 10-Year Prison Sentence in China For Writing Boys-Love Novels". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 2 December 2018.

- Keenapan, Nattha Japanese "boy-love" comics a hit among Thais Japan Today 2001

- Welker, James (2006). "Beautiful, Borrowed, and Bent: "Boys' Love" as Girls' Love in Shôjo Manga". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 31 (3): 3. doi:10.1086/498987.

- Antonia, Levi (2008). "North American reactions to Yaoi". In West, Mark (ed.). The Japanification of Children's Popular Culture. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 147–174. ISBN 978-0-8108-5121-4.

- Yoo, Seunghyun (2002) Online discussions on Yaoi: Gay relationships, sexual violence, and female fantasy Archived 23 September 2002 at the Wayback Machine

- Solomon, Charles (14 October 2003). "Anime, mon amour: forget Pokémon—Japanese animation explodes with gay, lesbian, and trans themes". The Advocate. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2012.

- Boon, Miriam (24 May 2007). "Anime North's bent offerings". Xtra!. Archived from the original on 15 March 2008. Retrieved 23 April 2008.

- McLelland, Mark (2000). Male homosexuality in modern Japan. Routledge. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-7007-1300-4.

- Brenner, Robin E. (2007). Understanding Manga and Anime. Libraries Unlimited. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-59158-332-5.

- Lunsing, Wim (2001). Beyond Common Sense: Sexuality and Gender in Contemporary Japan. London and New York: Kegan Paul International. ISBN 978-0-7103-0593-0.

- "Roundtable: The Internet and Women's Transnational "Boys' Love" Fandom" (PDF). University of Wollongong: CAPSTRANS. October 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2008. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Wood, Andrea (2011). "Choose Your Own Queer Erotic Adventure: Young Adults, Boy's Love Computer Games, and the Sexual Politics of Visual Play". Over the Rainbow: Queer Children's and Young Adult Literature. University of Michigan Press. pp. 356–. ISBN 9780472071463.

- Glasspool, Lucy Hannah. (2013). "Simulation and database society in Japanese roleplaying-game fandoms: Reading boys’ love dojinshi online. Archived 14 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine" Transformative Works and Cultures, 12.

- Schodt, Frederik L. (1983) Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics. pages 100–101 Tokyo and New York: Kodansha International. ISBN 0-87011-752-1

- Ueno, Chizuko (1989) "Jendaaresu waarudo no "ai" no jikken" ("Experimenting with "love" in a Genderless World"). In Kikan Toshi II ("Quarterly City II"), Tokyo: Kawade Shobō Shinsha, ISBN 4-309-90222-7. Cited and translated in Thorn, 2004.

- Takemiya, Keiko. (1993) "Josei wa gei ga suki!?" (Women Like Gays!?) Bungei shunjū, June, pp. 82–83.

- Suzuki, Kazuko. (1999) "Pornography or Therapy? Japanese Girls Creating the Yaoi Phenomenon". In Sherrie Inness, ed., Millennium Girls: Today's Girls Around the World. London: Rowman & Littlefield, p.246 ISBN 0-8476-9136-5, ISBN 0-8476-9137-3.

- Hashimoto, Miyuki Visual Kei Otaku Identity—An Intercultural Analysis Archived 7 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Intercultural Communication Studies XVI: 1 2007 pp. 87–99

- McCaffery, Larry; Gregory, Sinda; Kotani, Mari; Takayuki, Tatsumi (n.d.) The Twister of Imagination: An Interview with Mariko Ohara

- Sakakibara, Shihomi (1998) Yaoi genron: yaoi kara mieta mono (An Elusive Theory of Yaoi: The view from Yaoi). Tokyo: Natsume Shobo, ISBN 4-931391-42-7.

- Buckley, Sandra (1991) "'Penguin in Bondage': A Graphic Tale of Japanese Comic Books", pp. 163–196, In Technoculture. C. Penley and A. Ross, eds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota ISBN 0-8166-1932-8

- Welker, James (2006). "Beautiful, Borrowed, and Bent: 'Boys' Love' as Girls' Love in Shôjo Manga'". Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. 31 (3): 843. doi:10.1086/498987.

- Noh, Sueen (2002). "Reading YAOI Comics: An Analysis of Korean Girls' Fandom" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007.

- Johnson-Woods, Toni, ed. (2010). Manga an anthology of global and cultural perspectives. New York: Continuum. p. 46. ISBN 978-1441107879.

- Blackarmor (19 February 2008) "A Follow-Up To the Yaoi Debate" http://blackarmor.exblog.jp/7508722/ Archived 17 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine (In Japanese.) Accessed 14 August 2008.

- Mizoguchi, Akiko. (2003) "Homophobic Homos, Rapes of Love, and Queer Lesbians: Yaoi as a Conflicting Site of Homo/ Hetero-Sexual Female Sexual Fantasy". Session 187, Association for Asian Studies Annual Meeting, New York, 27–30 March 2003. https://www.asian-studies.org/absts/2003abst/Japan/sessions.htm#187 Archived 14 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine Accessed 9 December 2014.

- Butcher, Christopher (18 August 2006). A Few Comments About The Gay/Yaoi Divide – Strong enough for a man, but made for a woman... Archived 20 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Johnson, M.J. (May 2002). "A Brief History of Yaoi" Archived 25 December 2004 at the Wayback Machine. Sequential Tart.

- McHarry, Mark. "Identity Unmoored: Yaoi in the West". In Thomas Peele, ed., Queer Popular Culture: Literature, Media, Film, and Television. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. ISBN 1-4039-7490-X. pp. 187–188.

- Thorn, Rachel Matt. (1993) "Unlikely Explorers: Alternative Narratives of Love, Sex, Gender, and Friendship in Japanese Girls' Comics." New York Conference on Asian Studies, New Paltz, New York, 16 October 1993.

- "Intersections: Conflicting Discourses on Boys' Love and Subcultural Tactics in Mainland China and Hong Kong". Intersections.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- Pilcher, Tim and Brad Brooks. The Essential Guide to World Comics. Collins & Brown. 2005. 124–125.

- Cha, Kai-Ming. "Embracing Youka Nitta" (Archive). Publishers Weekly. 5/9/2006.

- "Intersections: (A)cute Confusion: The Unpredictable Journey of Japanese Popular Culture". Intersections.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- Loo, Egan (4 April 2010). "Osaka Considers Regulating Boys-Love Materials". Anime News Network. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Loo, Egan (28 April 2010). "Osaka Lists 8 Boys-Love Mags Designated as 'Harmful' (Updated)". Anime News Network. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Anime, Honey's (10 March 2017). "Top 10 Yaoi Mangaka List". Honey's Anime. Archived from the original on 7 May 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- "Yaoi Creator Receives 10+ Year Prison Sentence Over Obscene Content". Anime. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- Camper, Cathy (2006). "Essay: "Yaoi" 101: Girls Love "Boys' Love"". The Women's Review of Books. 23 (3): 24–26. ISSN 0738-1433. JSTOR 4024580.

Further reading

- Angles, Jeffrey (2011). Writing the love of boys: origins of Bishōnen culture in modernist Japanese literature. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-6970-7.

- Aoyama, Tomoko (2013). "BL (Boys' Love) Literacy: Subversion, Resuscitation, and Transformation of the (Father's) Text". U.S.-Japan Women's Journal. 43 (1): 63–84. doi:10.1353/jwj.2013.0001.

- Aoyama, Tomoko (1988) "Male homosexuality as treated by Japanese women writers" in The Japanese Trajectory: Modernization and Beyond, Gavan McCormack, Yoshio Sugimoto eds. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-34515-4.

- Brient, Hervé, ed. (2012). Le Yaoi articles, chroniques, entretiens et manga (in French) ([Seconde édition, mise à jour et développée]. ed.). Versailles: Éditions H. ISBN 979-10-90728-00-4.

- Brienza, Casey (6 February 2004). "An Introduction to Korean Manhwa" Aestheticism.com

- Camper, Cathy (2006). "Boys, Boys, Boys: Kazuma Kodaka Interview". Giant Robot (42): 60–63. ISSN 1534-9845.

- Cooper, Lisa "Laugh it up" Newtype USA, October 2007 (Volume 6 Number 10)

- Frennea, Melissa (2011) "The Prevalence of Rape and Child Pornography in Yaoi"

- Yukari, Fujimoto (2004). "Transgender: Female Hermaphrodites and Male Androgynes"". U.S.-Japan Women's Journal. 27: 76.

- Van de Goor, Sophie (2010). "Abstracts". www.mos.umu.se. Archived from the original on 15 January 2010. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- Haggerty, George E. (2000). Encyclopedia of Gay Histories and Cultures. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8153-1880-4.

- Kakinuma Eiko, Kurihara Chiyo et al. (eds.), Tanbi-Shosetsu, Gay-Bungaku Book Guide, 1993. ISBN 4-89367-323-8

- KUCI Subversities 18 October 2010

- Levi, Antonia (1996) Samurai from Outer Space: Understanding Japanese Animation

- Levi, Antonia; McHarry, Mark; Pagliassotti, Dru, eds. (2010). Boys' Love Manga: Essays on the Sexual Ambiguity and Cross-Cultural Fandom of the Genre. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-4195-2.

- Lewis, Marilyn Jaye (editor), Zowie! It's Yaoi!: Western Girls Write Hot Stories of Boys' Love. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2006. ISBN 1-56025-910-8.

- Mautner, Chris (2007) "Introduction to yaoi, part 1"

- McCarthy, Helen, Jonathan Clements The Erotic Anime Movie Guide pub Titan (London) 1998 ISBN 1-85286-946-1

- McHarry, Mark (2011). "Girls Doing Boys Doing Boys: Boys' Love, Masculinity and Sexual Identities". In Perper, Timothy and Martha Cornog (Eds.) Mangatopia: Essays on Anime and Manga in the Modern World. New York: ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-1-59158-908-2

- McLelland, Mark; Nagaike, Kazumi; Suganuma, Katsuhiko; et al., eds. (2015). Boys Love Manga and Beyond: History, Culture, and Community in Japan. [S.l.]: University Press Of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1628461190.

- McLelland, Mark (2011). "Australia's 'Child-Abuse Materials' legislation, internet regulation and the juridification of the imagination". International Journal of Cultural Studies. 15 (5): 467. doi:10.1177/1367877911421082.

- McLelland, Mark Australia's proposed internet filtering system : its implications for animation, comic and gaming (ACG) and slash fan communities Media international Australia, incorporating Culture & policy, 134, 2010, 7-19

- Kazumi Nagaike (3 May 2012). Fantasies of Cross-Dressing: Japanese Women Write Male-Male Erotica. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-21695-2. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- Nishimura Mari (2001) Aniparo to Yaoi Ohta Publishing ISBN 978-4-87233-643-6

- Newtype USA, August 2007 (Volume 6 Number 8) "Why we like it"

- Newtype USA, November 2007 (Vol. 6 No. 11) "Favorite authors" p. 109

- Ogi, Fusami (2001). "Beyond Shoujo, Blending Gender: Subverting the Homogendered World in Shoujo Manga (Japanese Comics for Girls)"". International Journal of Comic Art. 3 (2): 151–161.

- Pilcher, Tim; Moore, Alan; Kannenberg, Gene Jr. (2009). Erotic Comics 2: A Graphic History from the Liberated '70s to the Internet. Abrams ComicArts. ISBN 978-0-8109-7277-3.