Beauman Division

The Beauman Division was an improvised formation of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) during the Second World War, which fought in France against the German 4th Army in June 1940, during Fall Rot (Case Red), the final German offensive of the Battle of France.

| Beauman Division | |

|---|---|

_in_France_1939-1940_F4529.jpg) Men of the 4th Battalion, Border Regiment in defensive positions, May 1940. The battalion defended the BEF lines of communication and became part of Beauforce, later A Brigade of the Beauman Division. | |

| Active | 27 May – 17 June 1940 |

| Disbanded | 17 June 1940 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | infantry |

| Role | ad hoc defensive force |

| Size | division |

| Part of | British Lines of Communication, French Tenth Army |

| Engagements | Operation Red/Fall Rot |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Archibald Bentley Beauman |

Background

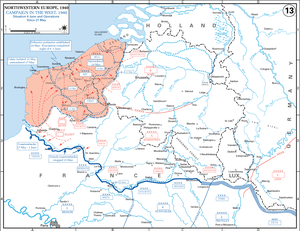

Battle of France

After the Phoney War, the Battle of France began on 10 May 1940 when the German armies in the west commenced the "Manstein Plan" Fall Gelb. The German Army Group B invaded the Netherlands and advanced westwards. General Maurice Gamelin, the Supreme Allied Commander, initiated the Dyle Plan (Plan D) and invaded Belgium to close up to the Dyle River with three mechanised armies, the French First Army and Seventh Army and the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). The plan relied on the Maginot Line fortifications along the German-French border but the Germans had already crossed through most of the Netherlands, before the French forces arrived. Army Group A advanced through the Ardennes and crossed the Meuse at Sedan on 14 May and then attacked down the Somme valley.[1]

On 19 May, an attack by the 7th Panzer Division (Generalmajor Erwin Rommel) on Arras was repulsed. During the evening, the SS Division Totenkopf (Gruppenführer Theodor Eicke) arrived on the left flank of the 7th Panzer Division. The 8th Panzer Division, further to the left, reached Hesdin and Montreuil and the 6th Panzer Division captured Doullens, after a day-long battle with the 36th Infantry Brigade of the 12th (Eastern) Division; advanced units pressed on to Le Boisle. On 20 May, the 2nd Panzer Division covered 56 miles (90 km) straight to Abbeville on the English Channel. Luftwaffe attacks on Abbeville increased and the Somme bridges were bombed. At 4:30 p.m., a party from the 2/6th Queens of the 25th Infantry Brigade of the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division ran into a German patrol and reported that the Germans had got between the 2/6th and 2/7th Queens. The British infantry were short of equipment and ammunition and were soon ordered to retreat over the river but the 1/5th and 2/7th Queens found the bridges had been demolished by the bombing. The Germans captured the town at 8:30 p.m., and only a few British survivors managed to retreat to the south bank of the Somme.[2][lower-alpha 1] At 2:00 a.m. on 21 May, the German III Battalion, Rifle Regiment 2 reached the coast west of Noyelles-sur-Mer.[4]

The 1st Panzer Division captured Amiens and established a bridgehead on the south bank, over-running the 7th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment of the 37th (Royal Sussex) Infantry Brigade. Of the 701 men in the battalion, only 70 survived to be captured but the operation deterred the Germans from probing further.[5] The 12th (Eastern) Division and 23rd (Northumbrian) Division had been destroyed, the area between the Scarpe and the Somme had been captured, the British lines of communication had been cut and the Channel ports were threatened with capture. An Army Group A war diarist wrote that "Now that we have reached the coast at Abbeville, the first stage of the offensive has been achieved.... The possibility of an encirclement of the Allied armies' northern group is beginning to take shape".[6]

At 8:30 a.m., Air Component Hawker Hurricane pilots reported a German column at Marquion on the Canal du Nord and others further south. Fires were seen in Cambrai, Douai and Arras, which the Luftwaffe had bombed, but the Air Component was moving back to bases in England. Communications between the Advanced Air Striking Force (AASF) in the south, the Air Component units still in France in the north and the Air Ministry were disorganised; the squadrons in France had constantly to move bases and operate from unprepared airfields with poor telephone connexions. The AASF was cut off from the BEF, and the Air Ministry and England-based squadrons were too far away for close co-operation. Two squadrons of bombers in England reached the column seen earlier at 11:30 a.m. and bombed transports on the Bapaume road, the second squadron finding the road empty. After midday, General Alphonse Georges, the commander of the French field armies requested a maximum effort but the RAF flew only one more raid, by two squadrons from 6:30 p.m. around Albert and Doullens. During the night, Bomber Command and the AASF flew 130 sorties and lost five bombers.[7]

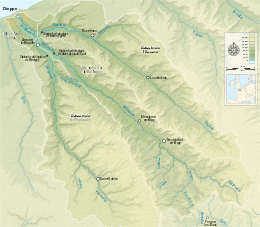

Lines of communication

The main BEF base ports were Cherbourg, Brest, Nantes and St Nazaire. When the expected Luftwaffe attacks against the sea traffic of the BEF did not materialise, Le Havre, Dieppe, Boulogne and Calais were also brought into use. The headquarters of the Lines of Communication were in Le Mans, where there was an important railway junction.[8] The area south of the Somme was the Northern District, commanded by Acting Brigadier Archibald Beauman, with Dieppe and Rouen comprising sub-areas. Dieppe was the main medical base of the BEF and Le Havre the principal supply and ordnance entrepôt. The BEF ammunition depot ran from St Saens to Buchy to the north-east of Rouen and infantry, machine-gun and base depots were at Rouen, Évreux and l'Épinay.[9]

A main railway line through Rouen, Abbeville and Amiens linked the bases and connected them with bases further west in Normandy and the BEF in the north. Beauman was responsible for base security and guarding 13 airfields being built with troops drawn from the Royal Engineers, Royal Army Ordnance Corps, Royal Corps of Signals and older garrison troops. Further south, in the Southern District, were three Territorial divisions and the 4th Border Regiment, the 4th Buffs and the 1st/5th Sherwood Foresters lines-of-communication battalions, which moved into the Northern District on 17 May as a precaution. Rail communications between the bases and the Somme quickly deteriorated, due to congestion and German bombing, trains from the north mainly carrying Belgian and French troops and the roads filling with retreating troops and refugees.[9]

Prelude

Formation

_in_France_1939-1940_F4542.jpg)

On 18 May 1940, Acting Brigadier Beauman, who was based at Rouen, was ordered by Major-General Philip de Fonblanque (General Officer Commanding Lines of Communication Troops) to strengthen his local defences. He formed Beauforce, consisting of Territorial infantry battalions that had been intended to protect lines of communication and undertake pioneer work. A second brigade-sized formation, Vicforce (named after its first commander, Colonel C. E. Vicary), was formed from five provisional battalions, made up of troops who had been employed in various depots, together with reinforcement drafts recently arrived in France.[10]

Beauman placed the force in a defensive position along the rivers Andelle and Béthune to defend Rouen and Dieppe from the east. Digforce was created by combining companies of the Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps into several battalions under Lieutenant-Colonel J. B. H. Diggle. These troops were mainly reservists who were not fit enough to join their front line units and had been detailed for construction and labour in the rear area.[11] On 29 May, the three improvised formations were combined to form the Beauman Division and Beauman was promoted to acting Major-General in command.[12] This was the first British division to be named after its commander since the Peninsular War.[13]

The use of the term "division" was to cause problems later, as it misled the French high command into thinking it was supported by artillery, engineers and signals in the same way as a regular division, rather than a collection of largely untrained troops armed only with light weapons.[14] A plan to withdraw all the improvised forces was dropped at the request of Georges, who said that such a course of action would have "an unfortunate effect on the French Army and the French people".[15]

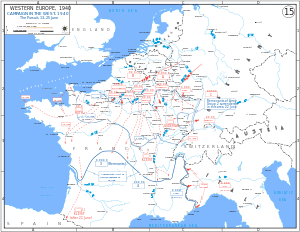

Battle

Beauman line

In the first days of June, the Beauman Division continued to construct what defences it could along the 55 mi (89 km) Andelle–Béthune line. On 6 June, it was reinforced by three infantry battalions; some artillery and engineer units arrived in the following days. "A" Brigade was detached to assist the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division (becoming part of Arkforce, formed to cover the retirement of the Highlanders towards Le Havre).[16] Some units of the 1st Armoured Division arrived in support but remained under the orders of the French Tenth Army commander, General Robert Altmayer. The difficulty of maintaining communications led Beauman to issue orders that units would hold on "as long as any hope of successful resistance remained" and that "Brigade commanders will use their discretion as regards withdrawal".[17]

At dawn on 8 June, the 5th Panzer Division and the 7th Panzer Division renewed their drive towards Rouen. The first German attacks were at Forges-les-Eaux and Sigy-en-Bray. At Forges, refugees prevented the blocking of roads; when a column of French tanks appeared, they were allowed to pass through. The tanks had been captured by the Germans and were used as a ruse. Once through the roadblocks, they attacked the British positions from the rear. The units of the division were pushed back and the line was penetrated in many places, despite the support of parts of the 1st Armoured Division on their left. Late in the afternoon, Syme's Battalion, only formed from depot troops in the previous week, held up the 5th Panzer Division for several hours outside Rouen, before being forced to retire south of the Seine. During the night, the remainder of the division retired across the river.[18]

Evacuation

_in_France_1939-1940_F4689.jpg)

The fragmented remains of the division that had escaped across the Seine were withdrawn to reorganise.[19] On 16 June, the Tenth Army ordered a general retirement with the eventual aim of establishing a defensive position on the Brittany peninsula; a policy opposed by both Brooke and the British Government. The Beauman Division was ordered to fall back on Cherbourg for Operation Ariel, evacuations from the French Atlantic and Mediterranean ports. This was relatively straightforward for the Beauman Division, which (unlike some other British formations) was not in contact with the Germans. The division crossed the line of retreat of part of the Tenth Army, which caused minor complications. Arriving at Cherbourg, the division embarked with whatever equipment they had and the division was evacuated by 17 June.[20] On arrival in England, the division was dispersed; the London Gazette for 16 August 1940 reported, "Colonel A. B. Beauman, CBE, DSO, relinquishes the acting rank of Major-General on ceasing to command a Division, 21st July 1940".[21]

Orders of battle

Beauman Division

- Formed 27 May 1940 Data from Karslake (1979) unless indicated.[22]

- Divisional Headquarters

- General Officer Commanding (Commander A): Major-General A. B. Beauman

- Commander Royal Artillery (CRA): Major G. Elliot, Royal Artillery

- Commander Royal Engineers (CRE): Lieutenant-Colonel J. B. H. Doyle, Royal Engineers

- Chief Signals Officer (CSO): Major W. A. Salt, Royal Corps of Signals

- Staff

- HQ staff and signals drawn from HQ North District

- General Staff Officer I (GSO I): Major A. N. S. Corbett, RA

- GSO II: Captain J. G. Churcher, KSLI

- GSO III: Captain G. S. Lowden, Y & L

- GSO III (I): Captain D. G. Dawes, RA

- Attached: Major D. G. I. A. Gordon, Gordon Highlanders

- Adjutants and Quartermasters (A and Q)

- Assistant Adjutant and Quartermaster General (AA and QMG): Colonel H. F. Grant-Suttie, RA

- Deputy Assistant Adjutant General (DAAG): Major R. A. Lake, Northants

- Deputy Assistant Quartermaster General (DAQMG): Major M. C. E. Sharpe, S. Lancs

- Attached: Captain D. M. Gall, Cameronians (Camp Commandant)

- Attached: Captain E. P. Dickson RE

Troops

A Brigade (late Beauforce) Brigadier M. A. Green (to 51st Highland Division 7 June, Arkforce 9 June) Data from Karslake (1979) unless indicated.[23]

- Previously 25th Infantry Brigade used on line-of-communications defence

- Brigadier M. A. Green (to 51st (Highland) Division, 7 June)

- 4th Battalion, Royal East Kent Regiment (Buffs) (from 27 May, Lieutenant- Colonel F. J. E. Marshall)[10]

- 2/6th Battalion, East Surrey Regiment (to 3 June) (Lieutenant-Colonel H. S. Burgess)

- 4th Battalion, Border Regiment (Lieutenant-Colonel T. W. A. Tomlinson from 3 June, detached to 1st Armoured Division by 6 June)

- 1/5th Battalion, Sherwood Foresters (from 27 May, Major B. D. Shaw)

- Brigade Carrier Platoon

- "D" Machine Gun Company (improvised from Cheshire and Manchester regiment troops in No 5 Infantry Base Depot)

B Brigade (late Vicforce) Data from Karslake (1979) unless indicated.[23]

- Provisional battalions formed of reinforcement and depot troops

- Brigadier Kent-Lemon

- Meredith's Rifle Battalion (Major H. R. H. Davies, later renamed Merry's Rifles, then 1st Battalion)[10]

- Davie's Rifle Battalion (Major W. W. Harrowing later renamed 2nd Provisional Battalion)[10]

- Ray's Rifle Battalion (later renamed Newcombe's Rifles, then 3rd Provisional Battalion)[10]

- Perowne's Rifle Battalion (disbanded and split between Ray's, Davie's and Meredith's Rifles by 1 June)[10]

- Waite's Rifle Battalion (disbanded and split between Ray's, Davie's and Meredith's Rifles by 1 June)[10]

- Brigade Anti-Tank Company (2 × 2-pounder and 2 × 25 mm Hotchkiss anti-tank guns; later renamed Z AT Company)

- Brigade Carrier Platoon

C Brigade (late Digforce) Data from Karslake (1979) unless indicated.[23]

- Provisional battalions formed of infantry reservists serving in the Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps (AMPC)

- Lieutenant-Colonel J. B. H. Diggle, 9th Lancers

- A Battalion (Nos 3, 10, 18 and 28 Companies AMPC from Rennes Sub-Area)

- B Battalion (Nos 5, 21 and 111 Companies AMPC from Nantes Sub-Area)

- C Battalion (Nos 4, 13, 113 and 114 Companies AMPC from Nantes Sub-Area)

- S (Scots) Infantry Battalion (formed from General Base Depot troops on 14 June; joined C Brigade 15 June)

- Brigade Carrier Platoon

- Divisional Troops

- Syme's Rifle Battalion (formed in late May with troops from the reinforcement depot, from 6 June retained under divisional control)[17]

- 2/4th Battalion, King's Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (from 46th Division)[17]

- 2/6th Battalion, Duke of Wellington's (from 46th Division)[17]

- E Anti-tank Regiment (12 × 2-pounder anti-tank guns (later 14); improvised from base reinforcement details and men returning from leave)

- X Field Battery (12 × 18-pounder field guns; improvised from base reinforcement details; many guns lacked dial sights.)[24]

- Divisional Tank Company (5 × Matilda I [Infantry Tank Mk I] and 5 [later 6] × Matilda II [Infantry Tank Mk II], later also 1 × cruiser tank and 1 × armoured car, formed from 27 May)

Arkforce

- Brigadier A. C. L. Stanley-Clarke (formed 9 June) Data from Karslake (1979) unless indicated.[27]

- 4th Battalion, Black Watch (from 153rd Brigade)

- 7th Battalion Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (from 154th Brigade)

- 8th Battalion Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (from 154th Brigade)

- 6th Battalion Royal Scots Fusiliers (Pioneers)

- A Brigade (Beauman Division)

- 1st Battalion Princess Louise's Kensington Regiment (less two companies)

- 17th Field Regiment RA

- 75th Field Regiment RA

- 51st Anti-tank Regiment RA (one battery)

- 236th Field Company RE

- 237th Field Company RE

- 239th Field Company RE

- 154th Field Ambulance

Normanforce

- Lieutenant-General J. H. Marshall-Cornwall (from 15 June) Data from Karslake (1979) unless indicated.[28]

- 3rd (Composite) Armoured Brigade (Brigadier John Crocker)

- Beauman Division (Acting Major-General A. B. Beauman, less A Brigade)

- 157th Brigade Group, 52nd (Lowland) Division (Brigadier Sir John Laurie)

- 71st Field Regiment RA, 52nd (Lowland) Division

- 5th Battalion King's Own Scottish Borderers, 52nd (Lowland) Division

- 1 × troop anti-tank guns

- 1 × company sappers

Regular infantry south of the Somme 20 May – 20 June 1940. Data from Karslake (1979) unless indicated.[28]

- 51st (Highland) Division 13 × battalions

- 52nd (Lowland) Division 9 × battalions

- 1st Canadian Division 3 × battalions

- Total 25 × battalions

After 20 May, there were 20 infantry battalions on the lines of communication (L of C). Data from Karslake (1979) unless indicated.[28]

- L of C troops 5 × battalions

- Beauman Division (excepting above) 7 × battalions

- 12th Division 5 × battalions

- 46th Division 3 × battalions

- Total 20 × battalions

From 20 May – 19 June, a grand total of 45 infantry battalions (equivalent to approximately 32,000 men) and 17 artillery regiments.[28]

Notes

- The 25th Infantry Brigade discovered that it had lost 1,166 of 2,400 men when the remnants rallied at Rouen on 23 May. The 2/5th Queens had 178 survivors, the 2/6th was intact except for one platoon and the 2/7th had 356 men left.[3]

Footnotes

- MacDonald 1986, p. 8.

- Karslake 1979, pp. 70–71.

- Karslake 1979, p. 71.

- Frieser 2005, p. 274.

- Karslake 1979, p. 67.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 80–81, 85.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 81–83.

- Beauman 1960, p. 98.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 252–254.

- Ellis 2004, p. 253.

- Karslake 1979, pp. 74–76.

- Glover 1985, p. 150.

- Beauman 1960, p. 140.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 279–281.

- Ellis 2004, p. 265.

- Ellis 2004, p. 279.

- Ellis 2004, p. 280.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 280–282.

- London Gazette 21/05/46 (pp. 2,438-2,439)

- London Gazette 21/05/46 (p. 2439)

- Second Supplement to The London Gazette of Tuesday 13 August 1940 (p, 5,001)

- Karslake 1979, pp. 249–251.

- Karslake 1979, p. 250.

- Hastings 2009, p. 43.

- Ellis 2004, pp. 367, 253.

- Ellis 2004, p. 365.

- Karslake 1979, pp. 250–251.

- Karslake 1979, p. 251.

References

- Beauman, Brigadier General A. B. (1960). Then a Soldier. London: Macmillan. OCLC 1891919.

- Ellis, Major L. F. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1953]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The War in France and Flanders 1939–1940. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-056-6. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- Frieser, K-H. (2005). The Blitzkrieg Legend. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-294-2.

- Glover, M. (1985). The Fight for the Channel Ports: Calais to Brest 1940: A Study in Confusion. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-436-18210-5.

- Hastings, M. (2009). Finest Years: Churchill as Warlord 1940–45. London: Harper Press. ISBN 978-0-00-726368-4.

- Karslake, B. (1979). 1940 The Last Act: The Story of the British Forces in France After Dunkirk. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-85052-240-2.

- MacDonald, John (1986). Great Battles of World War II. Toronto, Canada: Strathearn Books. ISBN 978-0-86288-116-0.

Further reading

- Rowe, V. (1959). The Great Wall of France: The Triumph of the Maginot Line (1st ed.). London: Putnam. OCLC 773604722.