Fort Mims massacre

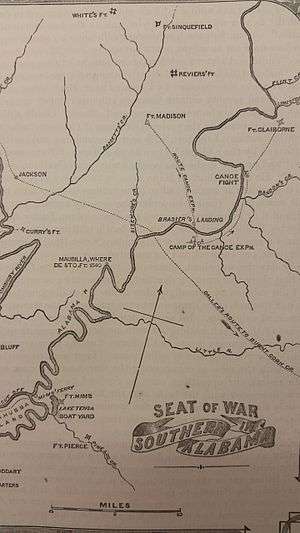

The Fort Mims massacre took place on August 30, 1813, during the Creek War, when a force of Creek Indians belonging to the Red Sticks faction, under the command of head warriors Peter McQueen and William Weatherford (also known as Lamochattee or Red Eagle), stormed the fort and defeated the militia garrison. Afterward, a massacre ensued and almost all of the remaining Creek métis, white settlers, and militia at Fort Mims were killed. The fort was a stockade with a blockhouse surrounding the house and outbuildings of the settler Samuel Mims, located about 35 miles directly north of present-day Mobile, Alabama.

Background

The Creek Nation split into factions, coinciding with the War of 1812. One group of Creek nativists, the Red Sticks, argued against any more accommodation of the white settlers while the other Creeks favored adopting the white lifestyle. The Red Stick faction from the Upper Towns opposed both land cessions to settlers and the Lower Towns' assimilation into European-American culture. The Natives were soon called "Red Sticks" because they had raised the "red stick of war," a favored weapon and symbolic Creek war declaration. Civil war among the Creeks erupted in the summer of 1813[8] and the Red Sticks attacked accommodationist headmen and, in the Upper Towns, began a systematic slaughter of domestic animals, most of which belonged to men who had gained power by adopting aspects of European culture. Not understanding internal issues among the Creek, frontier whites were alarmed about rising tensions and began 'forting up' and moving into various posts and blockhouses such as Fort Mims while reinforcements were sent to the frontier.[8]

American spies learned that Peter McQueen's party of Red Sticks were in Pensacola, Florida to acquire food assistance, supplies, and arms from the Spanish.[9] The Creek received from the newly arrived Spanish governor, Mateo González Manrique, 45 barrels of corn and flour, blankets, ribbons, scissors, razors, a few steers, and 1000 pounds of gunpowder and an equivalent supply of lead musket balls and bird shot.[10] When reports of the Creek pack train reached Colonel Caller, he and Major Daniel Beasley of the Mississippi Volunteers led a mounted force of 6 companies, 150 white militia riflemen, and 30 Tensaw métis (people of mixed American Indian and Euro-American ancestry) under Captain Dixon Bailey to intercept those warriors. James Caller (Call/Cole) ambushed the Red Sticks in the Battle of Burnt Corn in July 1813[11] as the Creek were having their mid-day meal.[12] While the United States forces were looting the pack trains, the warriors returned and successfully drove off the Americans. The United States was now at war with the Creek Nation.

In August 1813, Peter McQueen and Red Eagle (Weatherford) were the Red Stick chiefs who led the attack on Fort Mims. Nearly 1,000 warriors from thirteen Creek towns of the Alabamas, the Tallapoosas, and lower Abekas gathered at the mouth of Flat Creek on the lower Alabama River.[13]

The mixed blood whites who were called Creeks of Tensaw, who had relocated from Upper Creek Towns with the approval of the Creek National Council, joined European-American settlers in taking refuge within the stockade of Fort Mims. There were about 517 people,[3][14] including some 265 armed militiamen in the fort.[3] Fort Mims was located about 35 to 45 miles (50–70 km) directly north of Mobile on the eastern side of the Alabama River.[15]

Attack

On August 29, 1813, two black slaves tending cattle outside the stockade reported that "painted warriors" were in the vicinity, but mounted scouts from the fort found no signs of the war party. Major Beasley, the commander, had the second slave flogged for "raising a false alarm".[16] Beasley received a second warning the morning of the assault by a mounted scout, but dismissed it and took no precautions, as he was reportedly drunk.[17]

Beasley had claimed that he could "maintain the post against any number of Indians", but historians believe the stockade was poorly defended. At the time of the attack, the east gate was partially blocked open by drifting sand. Beasley also posted no pickets or sentries, dismissing the reports the Creeks were near.

The Red Sticks attacked during the mid-day meal, attempting to take the fort in a coup de main by charging the open gate en masse. At the same time, they took control of the gun loopholes and the outer enclosure. Under Captain Bailey, the militia and settlers held the inner enclosure, fighting on for a time; after about two hours there was a pause of about an hour.[18] The Indians, their initial impetus blunted inside the fort and casualties rising, held an impromptu council to debate whether to continue the fight or withdraw.[19] By 3 o'clock, it was decided that the Tensaw Native Americans led by Dixon Bailey would have to be killed to avenge their treachery at Burnt Corn.

The Creeks launched a second attack at 3 pm. The remaining defenders fell back into a building called the 'bastion'. The Red Sticks set fire to the 'bastion' in the center, which then spread out to the rest of the stockade.[20] The warriors forced their way into the inner enclosure and, despite attempts by Weatherford,[21] killed most of the militia defenders, the mixed-blood Creek, and white settlers. After a struggle of hours, the defense collapsed entirely and perhaps 500 militiamen, settlers, slaves and Creeks loyal to the Americans died or were captured, with the Red Sticks taking some 250 scalps. By 5 pm, the battle was over and the stockade and buildings sacked and in flames. While they spared the lives of almost all of the slaves, they took over 100 of them captive.[22] At least three women and ten children are known to have been made captive.[23] Some 36 people, nearly all men, escaped,[3] including Bailey, who was mortally wounded, and two women and one girl.[24] When a relief column arrived from Fort Stoddard (Mount Vernon, Alabama) a few weeks later, it found 247 corpses of the defenders and 100 of the Creek attackers.[25]

After their victory, the Red Sticks "razed the surrounding plantations.... They slaughtered over 5,000 head of cattle, destroyed crops and houses, and murdered or stole slaves."[26]:264

Aftermath

Fort Mims Site | |

Inside the reconstructed fort, looking at the west wall and gate. | |

| |

| Nearest city | Tensaw, Alabama |

|---|---|

| Area | 5 acres (2.0 ha) |

| Built | 1813 |

| NRHP reference No. | 72000153[27] |

| Added to NRHP | September 14, 1972 |

The Red Sticks' victory at Fort Mims spread panic throughout the Southeastern United States frontier, and settlers demanded government action and fled. In the weeks following the battle, several thousand persons, about half the population of the Tensaw and Tombigbee districts, fled their settlements for Mobile, which, with a population of 500, struggled to accommodate them.[28] The Red Stick victory, one of the greatest achieved by Native Americans,[29] and massacre marked the transition from a civil war within the Creek tribe (Muskogee) to a war between the United States and the Red Stick warriors of the Upper Creek.[25]

Since Federal troops were occupied with the northern front of the War of 1812, Tennessee, Georgia, and the Mississippi Territory mobilized their militias to move against the Upper Creek towns that had supported the Red Sticks' cause. After several battles, Major General Andrew Jackson commanded these state militias and together with Cherokee allies defeated the Red Sticks Creek faction at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, ending the Creek War.

Today, the Fort Mims site is maintained by the Alabama Historical Commission. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on September 14, 1972.[27]

The Fort Mims massacre is cited in Margaret Mitchell's epic novel Gone with the Wind. In the book, a minor character, Grandma Fontaine shares her memories of seeing her entire family murdered in the Creek uprising following the massacre as a lesson to the protagonist, Scarlett. She explains that a woman should never experience the worst that can happen to her, for then she can never experience fear again.[30]

See also

- List of Indian massacres

- List of massacres in Alabama

- Mississippi Rifles {155th Infantry MNG}

- Tombigbee District

Notes

- Waselkov, p. 99.

- Heidler, p. 133. Waselkov, p. 4, gives 700.

- Thrapp, p. 1524

- Halbert, Ball, p. 148.

- Heidler, p. 355, gives 100

- Heidler, p.355, gives 247.

- Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 756.

- Heidler, p. 354.

- Waselkov, pp. 99–100.

- Waselkov, p. 100.

- David Heidler and Jeanne T. Heidler, eds. Encyclopedia of the War of 1812 (2004) p. 106.

- Waselkov. p. 115.

- Waselkov, pp. 110–111.

- Halber, Ball, p. 148, gives 553.

- "Fort Mims" Archived 2008-05-30 at the Wayback Machine, Alabama Historical Commission.

- Abbott, John S. C., David Crockett: His Life and Adventures, Dodd and Mead, 1874, Chapter 3. Halbert, Ball, p. 150.

- Halbert, Ball, p. 152.

- Halbert, Ball, p. 158.

- Waselkov, p. 131

- Halbert, Ball, p. 156.

- Halbert, Ball, p. 155. Heidler, p. 355.

- Waselkov, p. 33, gives 100 or so slaves in the fort.

- Waselkov, p. 135.

- Waselkov, p. 134.

- Heidler, p. 355.

- Saunt, Claudio (1999). A New Order of Things. Property, Power, and the Transformation of the Creek Indians, 1733–1816. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521660432.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Waselkov, p. 142.

- Waslkov, p. 138

- Margaret Mitchell (1936). Gone With the Wind. Library Binding. pp. 452–53. ISBN 978-1439570838.

References

- Adams, Henry. History of the United States of America During the Administrations of James Madison (Library Classics of the United State, Inc. 1986), pp. 780–781 ISBN 0-940450-35-6

- Burstein, Andrew. The Passions of Andrew Jackson (Alfred A. Kopf 2003), p. 99 ISBN 0-375-41428-2

- Ehle, John. Trail of Tears The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation (Anchor Books Editions 1989), p. 105 ISBN 0-385-23954-8

- Halbert, Henry S., Ball, Timothy H.. The Creek War of 1813 and 1814, Chicago, 1895.

- Heidler, David Stephen and Heidler, Jeanne T. "Creek War," in Encyclopedia of the War of 1812, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 1997. ISBN 978-0-87436-968-7

- Mahon, John K.. The War of 1812 (University of Florida Press 1972) pp. 234–235 ISBN 0-8130-0318-0

- Owsley, Jr., Frank L. "The Fort Mims Massacre," Alabama Review 1971 24(3): 192-204

- Owsley, Frank L., Jr. Struggle for the Gulf Borderlands: The Creek War and the Battle of New Orleans, 1812-1815, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 1981.

- Thrapp, Dan L. "Weatherford, William (Lamouchattee, Red Eagle)", in Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography: in Three Volumes Lincoln : University of Nebraska Press, 1991. OCLC 23583099

- Waselkov, Gregory A.. A Conquering Spirit: Fort Mims and the Redstick War of 1813-1814 (University of Alabama Press, 2006) ISBN 0-8173-1491-1

External links

- Fort Mims - official site at Alabama Historical Commission

- "Fort Mims Massacre", Encyclopedia of Alabama

- A map of Creek War Battle Sites, PCL Map Collection, University of Texas at Austin.

- "A Drawing of Fort Mims"

- Fort Mims Restoration Association

- Site about the Creek War including accounts, letters, etc.

- Jesse Griffin (survivor) letter W.S. Hoole Special Collections Library, The University of Alabama

- List of Redstick Creek Warriors participating in the massacre